The Discovery of Mens and the Unity of Self-Cognition in St. Augustine's De Trinitate X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michel Fattal, Du Logos De Plotin Au Logos De Saint Jean

MICHEL FATTAL, DU LOGOS DE PLOTIN AU LOGOS DE SAINT JEAN. VERS LA SOLUTION D’un PROBLÈME MÉTAPHYSIQUE? PARIS, LES ÉDITIONS DU CERF, 2016, 150 PP., ISBN 9782204109673. Reviewed by Pedro Paulo A. Funari University of Campinas – Unicamp Michel Fattal is a well-known philosopher, a specialist on logos from the Pre-Socratics to the mediaeval period, passing through Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics and beyond. He puts together classical philosophy and Christian epistemology in innovative ways, as is the case in his new volume on Logos in Plotinus and in Saint John. The book gathers a series of lectures, starting with a keynote speech, or lectio magistralis, at Rome in April 2011, followed by several others. Fattal lectured on a related topic in Brasília, 2016, at a Archai Unesco Chair meeting. Fattal started to explore Logos in ancient Greek taught as early as 1977 and continued doing so in his PhD dissertation (1980) and Pedro Paulo A. Funari Habilitation (2001), publishing overall 19 books and dozens of papers and chapters. This volume is the 17th in a series on the Logos, and it deals with the relational logos in both Plotinus and Saint John, particularly the relationship of the sensible and possible to understand, earth and heaven, humans and God. Logos as a philosophical concept implies putting together (function rassemblante et unifiante). Legein derives from the root *leg-, meaning putting together and choosing. Logos thus means relating, and so speaking, a discourse as composition (sunthesis). Parmenides considers the Logos as the critical reason, capable of splitting up being and non-being, what is true and what is false, krinai logo, to judge or split up by reason (Parmenides B7, 5D-K). -

La Théologie D'al-Farabi Et Son Effet Sur Sa Vision Politique: Suivant Sa

la théologie d’al-farabi et son effet sur sa vision politique : suivant sa tentative de conciliation entre platon et aristote Assia Ouail To cite this version: Assia Ouail. la théologie d’al-farabi et son effet sur sa vision politique : suivant sa tentative de conciliation entre platon et aristote. Philosophie. Université Paul Valéry - Montpellier III, 2019. Français. NNT : 2019MON30098. tel-03006633v2 HAL Id: tel-03006633 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03006633v2 Submitted on 16 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Délivré par UNIVERSITE PAUL VALERY 3 Préparée au sein de l’école doctorale E 58 Et de l’unité de recherche CRISES (E.A 4424) Spécialité : PHILOSOPHIE Présentée par OUAIL ASSIA LA THEOLOGIE D’AL -FÂRÂBÎ ET SON EFFET SUR SA VISION POLITIQUE Suivant sa Tentative de conciliation entre Platon et Aristote Soutenue le 1er Février 2019 devant le jury composé de M. Jean-Luc PÉRILLIÉ, MCF HDR, Université Paul Valéry Directeur de recherche M. Philippe VALLAT, Professeur, Université de Vienne Rapporteur M. Abbas MAKRAM, Professeur, ENS de Lyon Rapporteur M. Alonso TORDESILLAS, Professeur, Université d’Aix Marseille Membre du jury M. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Kevin Corrigan Present Position: Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Interdisciplinary Humanities Address: Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts Emory University S410 Callaway Center Tel: 404-727-6460 Email: [email protected] Languages: Speak: English, French Read: English, French, Latin, Greek, German, Spanish, Italian EDUCATION AND EXPERIENCE: 2015- Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies, Associated in Classics, Philosophy, Religion/Graduate division of Religion 2009-15 Chair/Director, ILA 2009- Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Interdisciplinary Humanities 2009- Associated in Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies 2007-2009 Director of Graduate Studies, ILA 2007- Associated in Classics, Philosophy and Religion 2006-2007 Senior Research Fellow, Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry 2005-2006 Interim Director, ILA 2004- Director, Medieval Studies 2003-2006 Director, Undergraduate Studies, Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts, Emory University 2003 - Professor (tenured), Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts, Emory University 2002-2003 Visiting Professor, Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts and Classics, Emory University 2001-2002 Visiting Professor, Humanities (Classics, Philosophy, Religion, Comparative Literature), Emory University 2000-2001 Director, Classical, Mediaeval and Renaissance Studies Programme (16 participating departments), Department of History, College of Arts and Science, University of Saskatchewan (and Associate Member) 2 . 1993-1994 Research Fellow, Department of Latin and Greek, University College London, England 1992- Full Professor 1991-1998 Dean, St. Thomas More College, University of Saskatchewan 1990- Associate Member, Department of Philosophy, College of Arts and Science, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Sask. 1989-1992 Associate Professor 1988- Associate Member, Department of Classics, College of Arts and Science, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Sask. 1986-1989 Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy (tenured, 1988), St. -

GERSON-Cv-Utoronto-Philosophy

Curriculum Vitae Lloyd P. Gerson February 12, 2014 I. Born: December 23, 1948, Chicago, Illinois II. Citizenship: US/Canadian III. Degrees: University of Toronto (Ph.D., philosophy, 1975); University of Toronto (M.A., philosophy, 1971); Grinnell College (B.A., philosophy and classics, 1970) IV. Academic Appointments: Professor, Dept. of Philosophy, University of Toronto, 1990 - present; Associate Professor, Dept. of Philosophy, U. of T., 1979-90; School of Graduate Studies, U. of T., 1981; Assistant Professor, Dept. of Philosophy, U. of T., 1975-9; Lecturer, Dept. of Philosophy, University of Toronto, 1974-5 V. Academic Honors: Phi Beta Kappa; Woodrow Wilson Fellowship; Woodrow Wilson Dissertation Fellowship; University of Toronto Open Fellowship; University of Toronto Connaught Research Fellowship; SSHRC Research Fellowship; FRSC VI. Doctoral Dissertation: The Unity of Plato's Parmenides. Thesis Committee: R.E. Allen/T.M. Robinson, John Rist, Joseph Owens VII. Research Languages: Ancient Greek; Latin; French; German; Italian; Spanish VIII. Professional Affiliations and Activities: American Philosophical Association; Canadian Philosophical Association; Board of Directors International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, 2004 - ; Executive Committee International Plato Society (1998- 2004); Board of Directors, Journal of the History of Philosophy, 2007 -. IX. Publications: (a) Books (i) Monographs On the Morality of Nations: The Normative Foundations of International Relations, in progress Plotinus’ Ennead V 5 “That the Intelligibles are not External to the Intellect”. Translation with Commentary and Introduction (Las Vegas, Parmenides Press, 2013), 214pp. From Plato to Platonism (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013), 345pp. Ancient Epistemology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 179pp. Aristotle and Other Platonists (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005, paper 2006) 335pp. -

Fate, Chance, and Fortune in Ancient Thought

FATE, CHANCE, AND FORTUNE IN ANCIENT THOUGHT LEXIS ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY Adolf Hakkert Publishing - Amsterdam Carlos Lévy and Stefano Maso editors 1. Antiaristotelismo, a cura di C. Natali e S. Maso, 1999 2. Plato Physicus, Cosmologia e antropologia nel ‘Timeo’, a cura di C. Natali e S. Maso, 2003 (out of print) 3. Alessandro di Afrodisia, Commentario al ‘De caelo’ di Aristotele, Frammenti del primo libro, a cura di A. Rescigno, 2005 (out of print) 4. La catena delle cause. Determinismo e antideterminismo nel pensiero antico e con- temporaneo, a cura di C. Natali e S. Maso, 2005 5. Cicerone ‘De fato’, Seminario Internazionale, Venezia 10-12 Luglio 2006, a cura di S. Maso, ex “Lexis” 25/2007, pp. 1-162 6. Alessandro di Afrodisia, Commentario al ‘De caelo’ di Aristotele, Frammenti del secon- do, terzo e quarto libro, a cura di A. Rescigno, 2008 7. Studi sulle Categorie di Aristotele, a cura di M. Bonelli e F.G. Masi, 2011 8. Ch. Vassallo, Filosofia e ‘sonosfera’ nei libri II e III della Repubblica di Platone, 2011 9. Fate, Chance, and Fortune in Ancient Thought, F.G. Masi - S. Maso (eds.), 2013 LEXIS ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY (ed. minor) Libreria Cafoscarina Editrice s.r.l. - Venezia Carlos Lévy and Stefano Maso editors 1. Plato Physicus, Cosmologia e antropologia nel ‘Timeo’, a cura di C. Natali e S. Maso, 2011 2. Cicerone ‘De fato’, Seminario Internazionale, Venezia 10-12 Luglio 2006, a cura di S. Maso, 2012 LEXIS ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY Adolf Hakkert Publishing - Amsterdam Carlos Lévy and Stefano Maso editors IX ADOLF M. HAKKERT – PUBLISHING Amsterdam 2013 Volume pubblicato con il parziale contributo PRIN 2009 responsabile prof. -

Bulletin D'information Et De Liaison 46 (2012)

ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONALE D’ÉTUDES PATRISTIQUES International Association of Patristic Studies Bulletin d’information et de liaison 46 (2012) Table des matières VIE DE L’ASSOCIATION 5 De la part du Président. • De la part du Secrétaire. • Cotisation et Adhésion. • Statuts de l’AIEP / IAPS comme modifiés à Oxford 2003 (texte français et traduction anglaise). • Règlement intérieur de l’AIEP / IAPS comme approuvé à Oxford 2011 (texte français et traduction anglaise). • Liste des membres du Conseil élus en 2003. • Liste des correspondants nationaux et du Comité exécutif. • Liste des nouveaux membres. • Liste des membres, anciens membres et collègues décédés. • Membres par pays. BULLETIN BIBLIOGRAPHIQUE : Travaux récemment parus ou en préparation 33 A. Bibliographie et histoire de la recherche 36 B. Ouvrages généraux I - Histoire du christianisme ancien 40 0. Christianisme et société dans l’antiquité tardive 42 1. Histoire des communautés, des institutions, des périodes, des régions 49 2. Histoire des doctrines (théologie) 63 3. Liturgie et hymnographie 67 4. Culture antique et culture chrétienne 73 5. Hagiographie et histoire de la spiritualité 82 6. Art et archéologie 85 7. Épigraphie 86 8. Codicologie (manuscrits, catalogues, microfilms, paléographie) 88 9. Papyrologie 88 10. Prosopographie II - Langues et littérature chrétiennes 89 1. Histoire des langues et des littératures classiques et orientales 91 2. Genres littéraires 94 3. Vocabulaire et stylistique 96 4. Thèmes littéraires 98 5. Patristique et Moyen Âge 102 6. Patristique et humanisme, Renaissance et Réforme, Temps modernes 105 7. Actualité des Pères III - La Bible et les Pères 108 0. Ouvrages généraux 111 1. Christianisme et judaïsme 114 2. -

Plotinus' Epistemology and His Reading of the Theaetetus

Plotinus' epistemology and his reading of the Theaetetus Sara Magrin Department of Philosophy McGill University, Montreal July 2009 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Copyright Sara Magrin 2009 Abstract: Plotinus' epistemology and his reading of the Theaetetus The thesis offers a reconstruction of Plotinus’ reading of the Theaetetus, and it presents an account of his epistemology that rests on that reading. It aims to show that Plotinus reads the Theaetetus as containing two anti-sceptical arguments. The first argument is an answer to radical scepticism, namely, to the thesis that nothing is apprehensible and judgement must be suspended on all matters. The second argument is an answer to a more moderate form of scepticism, which does not endorse a universal suspension of judgement, but maintains nonetheless that scientific knowledge is unattainable. The first chapter opens with a reconstruction of Plotinus’ reading of Theaet., 151e-184a, where Socrates examines the thesis that knowledge is sensation in light of Protagoras’ epistemology. In this chapter it is argued that Plotinus makes a polemical use of the discussion of Protagoras’ epistemology. Plotinus takes Plato to show that Protagoras’ views imply radical scepticism; and he attack the Stoics’ epistemological and ontological commitments by arguing that they imply Protagoras’ views, and thus lead to radical scepticism, too. The second chapter examines Plotinus’ interpretation of the ontology of the Timaeus. In Theaet., 151e-184a Plato shows that Protagoras’ epistemology leads to radical scepticism by arguing that it implies an allegedly Heracleitean conception of the sensible world. -

There's Always The

Peter VanNuffelen There’sAlwaysthe Sun Metaphysics and Antiquarianism in Macrobius Abstract: The present paper asks how Macrobius thinks his extensive allegories of statues of the gods and other elements of traditional religion are possible. He can be shown to espouse aNeoplatonic theory of images. This entails that truthful im- ages are onlypossible of the Soul and the lower levels of the world, whereas the two highest hypostases cannot be graspedbylanguageand man-made images. Even so, as the sun is an imageofthe highest principle, Macrobius’ reduction of all deities to the sun can be understood as adiscourse on the highest deity,albeit obliquely. How are images, then, truthful?Hedefends acommon theory of inspira- tion, accordingtowhich the creators of images participate in the Logoswhencreat- ing them. Philosophyisseen as the primordial discipline, containingthe knowledge necessary to create and interpret images. These conclusions allow us to pinpoint more preciselythe differences between Middle and Neoplatonism. How does one justify the use of man-made images of the divine if one posits asu- preme divine being that is beyond languageand discursive knowledge?More precise- ly:onwhat conditions can aNeoplatonist presume thatatraditionalcult imageof, say, Saturn, represents metaphysical truths?That myths, ceremonies, and cult im- ages could be interpreted as containing knowledge about the world is awell- known fact: allegoricalinterpretations are prominent in the Stoic and Platonist tra- dition.Ifscholars have often asked the question of what precise technique of allego- ry wasapplied to understand poetry,myth, and cult as philosophy, the question of how the sheer possibility of such an exercise was explained has onlyrecentlystarted to draw attention. -

The Philosophical Heritage of Desire for God in Ibn Ṭufayl's Ḥayy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duquesne University: Digital Commons Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 8-11-2018 The hiP losophical Heritage of Desire for God in Ibn Ṭufayl’s Ḥayy Ibn Yaqẓān Bethany Somma Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Somma, B. (2018). The hiP losophical Heritage of Desire for God in Ibn Ṭufayl’s Ḥayy Ibn Yaqẓān (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1468 This One-year Embargo is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PHILOSOPHIAL HERITAGE OF DESIRE FOR GOD IN IBN ṬUFAYL’S ḤAYY IBN YAQẒĀN A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and the Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Bethany Somma August 2018 Copyright by Bethany Somma 2018 1 THE PHILOSOPHIAL HERITAGE OF DESIRE FOR GOD IN IBN ṬUFAYL’S ḤAYY IBN YAQẒĀN By Bethany Somma Approved July 2, 2018 ___________________________ ____________________________ Dr. L. Michael Harrington Dr. Peter Adamson Associate Professor of Philosophy Professor of Late Antique and Arabic (Committee Chair) Philosophy, LMU Munich (Committee Co-chair) ____________________________ ____________________________ Dr. Thérèse Bonin Dr. Christof Rapp Associate Professor of Philosophy Professor of Ancient Philosophy (Committee Member) LMU Munich (Committee Member) ____________________________ ____________________________ Dr. -

Philosophy in Review/Comptes Rendus Philosophiques Academic Printing and Publishing

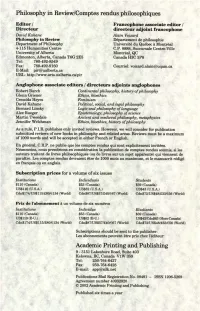

Philosophy in Review/Comptes rendus philosophiques Editor/ Francophone associate editor / Directeur directeur adjoint francophone David Kahane Alain Voizard Philosophy in Review Departement de philosophie Department of Philosophy Universite du Quebec a Montreal 4-115 Humanities Centre C.P. 8888, Succursale Centre-Ville University of Alberta Montreal, QC Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E5 Canada HSC 8P8 Tel: 780-492-8549 Fax: 780-492-9160 Courriel: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.arts.ualberta.ca/pir Anglophone associate editors / directeurs adjoints anglophones Robert Burch Continental philosophy, hist-Ory ofphilosophy Glenn Griener Ethics, bioethics Cressida Heyes Feminism DavidKahane Political, social, and legal philosophy Bemard Linsky Logic and philosophy of language Alex Rueger Epistemology, philosophy ofscience Martin Tweedale Ancient and medieval philosophy, metaphysics Jennifer Welchman Ethics, bioethics, history ofphilosophy As a rule, P.I.R. publishes only invited reviews. However, we will consider for publication submitted reviews of new books in philosophy and related areas. Reviews must be a maximum of 1000 words and will be accepted in either French or English. En general, C.R.P. ne publie que Jes comptes rendus qui sont explicitement invitees. Neanmoins, nous prendrions en consideration la publication de comptes rendus soumis, si Jes auteurs traitent de livres philosophiques (ou de livres sur un sujet apparente) qui viennent de paraitre. Les comptes rendus devraient etre de 1000 mots au maximum, -

By Wayne J. Hankey In

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF NEOPLATONISM IN FRANCE : A BRIEF PHILOSOPHICAL HISTORY by Wayne J. Hankey in Levinas and the Greek Heritage, by Jean-Marc Narbonne (pages 1-96), followed by One Hundred Years of Neoplatonism in France: A Brief Philosophical History, by Wayne Hankey (pages 97-248), Studies in Philosophical Theology (Leuven/Paris/Dudley, MA: Peeters, 2006) ISBN-10 90-429-1766-0 & ISBN-13 9789042917668. 2 Preface to the English Edition, Acknowledgements, and Dedication This essay has its origins more than twenty-five years ago, when I was working on what would become my God in Himself , a study of Aquinas’ doctrine of God. I desired to understand the reasons for a reversal I was discovering, one which enabled my particular treatment of St Thomas. It had become apparent to me that the “Aristotelian-Thomist philosophy” had largely given way within the French Catholic Church to more Platonic forms of philosophy, theology, and spirituality and that Aquinas had now been relocated within these. My quest spanning decades has been assisted by many who have passed, we may hope, to a far better reward than words of mine can bestow. I remember them all with joy and gratitude, but a memorial of one must be erected here: the sine qua non of my life in Paris was the never failing hospitality, friendship, learning, and the enthusiasm for the inquiry of which this book is the fruit of Bruno Charles Neveu. That he died while Cent ans was in press and was not able to see it added to my sorrow at his departure, a grief shared by the enormous flock of the scholars whom he supported and promoted so generously. -

Essays on Plato's Epistemology

ESSAYS ON PLATO’S EPISTEMOLOGY ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL PHILOSOPHY DE WULF-MANSION CENTRE Series I LIII Series Editors Russell L. Friedman Jan Opsomer Carlos Steel Gerd Van Riel Advisory Board Brad Inwood, University of Toronto, Canada Jill Kraye, The Warburg Institute, London, United Kingdom John Marenbon, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom Lodi Nauta, University of Groningen, The Netherlands Timothy Noone, The Catholic University of America, USA Robert Pasnau, University of Colorado at Boulder, USA Martin Pickavé, University of Toronto, Canada Pasquale Porro, Università degli Studi di Bari, Italy Geert Roskam, KU Leuven, Belgium The “De Wulf-Mansion Centre” is a research centre for Ancient, Medieval, and Renaissance philosophy at the Institute of Philosophy of the KU Leuven, Kardinaal Mercierplein, 2, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). It hosts the international project “Aristoteles latinus” and publishes the “Opera omnia” of Henry of Ghent and the “Opera Philosophica et Theologica” of Francis of Marchia. ESSAYS ON PLATO’S EPISTEMOLOGY Franco Trabattoni LEUVEN UNIVERSITY PRESS © 2016 by De Wulf-Mansioncentrum – De Wulf-Mansion Centre Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium) All rights reserved. Except in those cases expressly determined by law, no part of this publication may be multiplied, saved in an automated datafile or made public in any way whatsoever without the express prior written consent of the publishers. ISBN 978 94 6270 059 8 D/2016/1869/2 NUR: 732 To Giuliana, Giovanni and Anna Introduction Thought as Inner Dialogue (Theaet. e–a) Logos and doxa: The Meaning of the Refutation of the Third Definition of Epistêmê in the Theaetetus Theaetetus d–c: Truth without Certainty Foundationalism or Coherentism? On the Third Definition of Epistêmê in the Theaetetus What is the Meaning of Plato’s Theaetetus? Some Remarks on a New Annotated Translation of the Dialogue David Sedley’s Theaetetus The “Virtuous Circle” of Language.