The Inflicted Livestock Ban and Poor 'Gu' Rains with Latent Drought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Hum Ethio Manitar Opia Rian Re Espons E Fund D

Hum anitarian Response Fund Ethiopia OCHA, 2011 OCHA, 2011 Annual Report 2011 Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Humanitarian Response Fund – Ethiopia Annual Report 2011 Table of Contents Note from the Humanitarian Coordinator ................................................................................................ 2 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 2011 Humanitarian Context ........................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Map - 2011 HRF Supported Projects ............................................................................................. 6 2. Information on Contributors ................................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Donor Contributions to HRF .......................................................................................................... 7 3. Fund Overview .................................................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Summary of HRF Allocations in 2011 ............................................................................................ 8 3.1.1 HRF Allocation by Sector ....................................................................................................... -

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

Hydrological Extremes and Their Association with ENSO Phases in Ethiopia

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/681528; this version posted June 24, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Hydrological Extremes and their Association with ENSO Phases in Ethiopia Abu Tolcha Gari Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research Corresponding author: Email: [email protected]; Tel: +251-9-1281-2790, Fax: +251-022-331-1508 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/681528; this version posted June 24, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Abstract Ethiopia is a rain fed agriculture country, which is subjected to high climate variability in space and time, leading to hydrological extremes causing loss of life and property more frequently. Droughts are more common and sometime floods are experienced in various parts of the country. Being a tropical country, the inter-annual climate variability in Ethiopia is dominated by ENSO (ElNino and Southern Oscillation). In this study, an attempt has been made to determine the occurrence of droughts and floods on monthly basis, by calculating the monthly SPI (Standardized Precipitation Index) using the available rainfall data during (1975-2005) at selected 26 stations that spread across the country. Based on the monthly SPI values computed, the droughts and floods of different intensities; extreme, severe and dry have been determined for all stations. -

Management Plan of Babile Elephant Sanctuary

BABILE ELEPHANT SANCTUARY MANAGEMENT PLAN December, 2010 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Wildlife for Sustainable Authority (EWCA) Development (WSD) Citation - EWCA and WSD (2010) Management Plan of Babile Elephant Sanctuary. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 216pp. Acronyms AfESG - African Elephant Specialist Group BCZ - Biodiversity Conservation Zone BES - Babile Elephant Sanctuary BPR - Business Processes Reengineering CBD - Convention on Biological Diversity CBEM - Community Based Ecological Monitoring CBOs - Community Based Organizations CHA - Controlled Hunting Area CITES - Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora CMS - Convention on Migratory Species CSA - Central Statistics Agency CSE - Conservation Strategy of Ethiopia CUZ - Community Use Zone DAs - Development Agents DSE - German Foundation for International Development EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EPA - Environmental Protection Authority EWA - Ethiopian Wildlife Association EWCA - Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority EWCO - Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Organization EWNHS - Ethiopian Wildlife and Natural History Society FfE - Forum for Environment GDP - Gross Domestic Product GIS - Geographic Information System ii GPS - Global Positioning System HEC – Human-Elephant Conflict HQ - Headquarters HWC - Human-Wildlife Conflict IBC - Institute of Biodiversity Conservation IRUZ - Integrated Resource Use Zone IUCN - International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources KEAs - Key Ecological Targets -

Measles Outbreak Investigation and Response in Jarar Zone of Ethiopian Somali Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia

International Journal of Microbiological Research 8 (3): 86-91, 2017 ISSN 2079-2093 © IDOSI Publications, 2017 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.ijmr.2017.86.91 Measles Outbreak Investigation and Response in Jarar Zone of Ethiopian Somali Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia 12Yusuf Mohammed and Ayalew Niguse 1Ethiopian Somali Regional Health Bureau, Jigjiga, P.O. Box: 238, Jigjiga, Ethiopia 2Department of Microbiology and Public Health, Jigjiga University, P.O. Box: 1020, Jigjiga, Ethiopia Abstract: Suspected measles outbreak was notified from Degahbour hospital to the Emergency Management Team at the Regional Health Bureau. A team of experts was dispatched to the site with the objectives of confirming the existence of the outbreak, initiate measures and formulate recommendations based on the results of present outbreak investigation. We conducted descriptive cross sectional study from February to March 2016. We reviewed medical records of suspected cases; we interviewed the Health care workers, visited affected household and interviewed parents and guardians of cases. We used line list for describing measles cases interms of time, place and person. We collected five blood samples from patients for Lab confirmation. We entered and analyzed using Epi-Info7 version 7.1.0.6. During the investigation period, 406 measles cases with 5 deaths were reported with overall Attack Rate (AR) and Case Fatality Rate (CFR) was (28.2/10, 000 population, 1.2%) respectively. High AR (28.6/10000population) was reported from male. The CFR difference was not statistically significant (P value=0.66) by sex. High AR (127/10000population) was reported from age group < 1 years. When we compared AR by those < 5 years and >5 years, there was statistically significant difference (P-value= 0.00). -

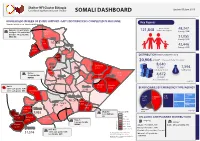

Somali Dashboard +Distribution Breakdown

Shelter-NFI Cluster Ethiopia Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SOMALI DASHBOARD Update 05 June 2018 HOUSEHOLDS IN NEED OF ES/NFI SUPPORT- GAP*/ DISTRIBUTIONS COMPLETED IN MAY/JUNE Key Figures *Number of HH inGA need - Number of HH suported HH in need of 48,347 Gablalu- 100 partial kits 121,848 Shelter/ NFI support Hadigala- 330 partial kits Gablablu Priority 1 HH Dembel- 140 partial kits 1,673 ERCS/IRC 31,055 Siti Priority 2 HH Erer 10,808 2,630 Fafan 42,446 Miesso Priority 3 HH 3,598 15,157 Jijiga DISTRIBUTION SINCE JANUARY 2018 Babile 1,464 10, 592 20,906 (2,482)* HH received Shelter/ NFI support Erer Gashamo 8,640 4,941 Jarar 3, 733 (1,390)* 7,594 Full Shelter/NFI kits Cash Grants Qubi 7, 343 S Berano Boh 2,114 500 partial kits Noqob Danot Doolo 1,546 4,672 NDRMC 2,537 (1,102)* 3,841 Gerbo 12,068 Partial Shelter/NFI kits 1,476 on-going* Warder Geladin Hudet Korahe 3,712 2,144 BENEFICIARIES BY EMERGENCY TYPE/AGENCY 1,500 cash grants- IOM 3,193 1,000 cash grants- NRC Guradamole Berano 2,720 290 NRC CONCERN CONFLICTIOM Shabelle FLOOD CONFLICT 3,630 2,602 9,0507,094 7,462 9,050 Karsa Dulla 16, 578 (2,482)* IRC/ERCS Afder Kelafo 2,570 1,449 Hargele 9,520 SCI 7,033 702 Mustahil 3,000 NDRMC 2,000 Deka Suftu 3,419 Liben DROUGHT 2,364 on-going* Mustahil Number of HH 3,814 9,955 1,000 fulll kits Hudet 0 SCI 1 - 500 12,718 Mubarak ON-GOING AND PLANNED DISTRIBUTIONS Dolo Odo 500 - 1,000 6,002 Hargele on-going 1,989 1,500 partial kits 1,000 - 2,000 planned 2,000 - 5,000 Moyale NDRMC Adadle- 750 full kits /NRC Kelafo- 450 partial kits /SCI 5,000 -

11 HS 000 ETH 013013 A4.Pdf (English)

ETHIOPIA:Humanitarian Concern Areas Map (as of 04 February 2013) Eritrea > !ª !ª> Note: The following newly created woreda boundaries are not Tahtay !ª E available in the geo-database; hence not represented in this Nutrition Hotspot Priority Laelay Erob R R !ª Adiyabo Mereb Ahferom !ª Tahtay Gulomekeda !ª I E map regardless of their nutrition hot spot priority 1 & 2: Adiyabo Leke T D Adiyabo Adwa Saesie Dalul Priority one Asgede Tahtay R S Kafta Werei Tsaedaemba E E Priority 1: Dawa Sarar (Bale zone), Goro Dola (Guji zone), Abichu Tsimbila Maychew !ª A Humera Leke Hawzen Berahle A Niya( North Showa zone) and Burka Dintu (West Hararge Priority two > T I GR AY > Koneba Central Berahle zone) of Oromia region, Mekoy (Nuer zone) of Gambella Western Naeder Kola Ke>lete Awelallo Priority three Tselemti Adet Temben region, Kersadula and Raso (Afder zone), Ararso, Birkod, Tanqua > Enderta !ª Daror and Yo'ale (Degahabour zone), Kubi (Fik zone), Addi Tselemt Zone 2 No Priority given Arekay Abergele Southern Ab Ala Afdera Mersin (Korahe zone), Dhekasuftu and Mubarek (Liben Beyeda Saharti Erebti Debark Hintalo !ª zone), Hadigala (Shinille zone) and Daratole (Warder Abergele Samre > Megale Erebti Bidu Wejirat zone) of Somali region. Dabat Janamora > Bidu International Boundary Alaje Raya North Lay Sahla Azebo > Wegera Endamehoni > > Priority 2: Saba Boru (Guji zone) of Oromia region and Ber'ano Regional Boundary Gonder Armacho Ziquala > A FA R !ª East Sekota Raya Yalo Teru (Gode zone) and Tulu Guled (Jijiga zone) of Somali region. Ofla Kurri Belesa -

Agency Deyr/Karan 2012 Seasonal

Food Supply Prospects FOR THE YEAR 2013 ______________________________________________________________________________ Disaster Risk Management and Food Security Sector (DRMFSS) Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) March 2013 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Table of Contents Glossary ................................................................................................................. 2 Acronyms ............................................................................................................... 3 EXCUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 11 REGIONAL SUMMARY OF FOOD SUPPLY PROSPECT ............................................. 14 SOMALI ............................................................................................................. 14 OROMIA ........................................................................................................... 21 TIGRAY .............................................................................................................. 27 AMHARA ........................................................................................................... 31 AFAR ................................................................................................................. 34 BENISHANGUL GUMUZ ..................................................................................... 37 SNNP ............................................................................................................... -

Peace in Puntland: Mapping the Progress Democratization, Decentralization, and Security and Rule of Law

Peace in Puntland: Mapping the Progress Democratization, Decentralization, and Security and Rule of Law Pillars of Peace Somali Programme Garowe, November 2015 Acknowledgment This Report was prepared by the Puntland Development Re- search Center (PDRC) and the Interpeace Regional Office for Eastern and Central Africa. Lead Researchers Research Coordinator: Ali Farah Ali Security and Rule of Law Pillar: Ahmed Osman Adan Democratization Pillar: Mohamoud Ali Said, Hassan Aden Mo- hamed Decentralization Pillar: Amina Mohamed Abdulkadir Audio and Video Unit: Muctar Mohamed Hersi Research Advisor Abdirahman Osman Raghe Editorial Support Peter W. Mackenzie, Peter Nordstrom, Jessamy Garver- Affeldt, Jesse Kariuki and Claire Elder Design and Layout David Müller Printer Kul Graphics Ltd Front cover photo: Swearing-in of Galkayo Local Council. Back cover photo: Mother of slain victim reaffirms her com- mittment to peace and rejection of revenge killings at MAVU film forum in Herojalle. ISBN: 978-9966-1665-7-9 Copyright: Puntland Development Research Center (PDRC) Published: November 2015 This report was produced by the Puntland Development Re- search Center (PDRC) with the support of Interpeace and represents exclusively their own views. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the contribut- ing donors and should not be relied upon as a statement of the contributing donors or their services. The contributing donors do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor do they accept responsibility for any use -

MIND the GAP Commercialization, Livelihoods and Wealth Disparity in Pastoralist Areas of Ethiopia

MIND THE GAP Commercialization, Livelihoods and Wealth Disparity in Pastoralist Areas of Ethiopia Yacob Aklilu and Andy Catley December 2010 Contents Summary ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Objectives .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Structure of the report .......................................................................................................................... 5 2. Livestock exports from pastoral areas of Ethiopia: recent trends and issues ......................................... 6 2.1 The growing trade: economic gains outweigh ethnicity and trust........................................................ 7 2.2 The cross‐border trade from Somali Region and Borana ...................................................................... 8 2.3 Trends in formal exports from Ethiopia .............................................................................................. 12 2.4 A boom in prices and the growth of bush markets ............................................................................