Crash No 107

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Llaaddiissllaavvkkuuddr

LvNZ-Ob.qxd 17.3.2005 11:21 StrÆnka 1 55 Vážení a milí čtenáři, kniha, kterou právě držíte, přináší 55 44 44 99 zcela nový pohled na téma Českoslovenští letci v němec - 99 11 11 –– kém zajetí 1940–1945. Většina dosavadní literatury se sou - –– 00 00 44 středila pouze na to, jak byl dotyčný letec, osádka, sestře - 44 99 99 len a jak následně upadl do zajetí. Ani autor této knihy se 11 11 ÍÍ nevyhnul popisu sestřelení a následného zajetí, které je ÍÍ TT TT EE ovšem zpracováno z širšího pohledu po důkladném vytěže - EE JJ JJ AA ní archivních materiálů. Autor této knihy začíná tím, co AA ZZ ZZ předcházelo sestřelení. Tedy, jak byli naši letci připraveni M M M M ÉÉ a vybaveni na možnost zajetí. Následuje popis sestřelení ÉÉ KK KK CC a následného zajetí. Čím je ovšem tato kniha zcela nová? CC EE EE Především tím, že kniha zajetím dotyčného letce nekončí, M M M M ĚĚ ale právě naopak, teprve zde kniha začíná. Kniha mimo jiné ĚĚ NN NN pojednává o organizaci zajateckého tábora a života v zaje - VV VV II tí samého. Jak probíhaly všední, ale i sváteční a výjimečné II CC CC TT dny v zajateckém táboře. Nebude vynechána ani otázka TT EE EE LL ú r o v n ě s t r a v o v á n í a u b y t o v á n í . V z t a h y m e z i z a j a t c i LL ÍÍ ÍÍ a německými strážnými. -

Anrc-Powb 1944-12

VO~. 2, ---...NO. II WOUNDED AMERICANS IN HUNGARY AND YUGOSLAVL\. At the end of June, the lot national Red Cross reported t~r. t th~re were l~ ~ound~d Americ: A U "If r-c N ;C~~~o~c'~o:~::~:;~~ "~:t.!!~~~n: It ISO N E R S 0 F W R B L L It :J" Hunganan mIl1tary hospital . ..... Budapest. A report on the v' ~t hed by the American National Red Cross for the Relatives of Amencan Pnsoners of War and CIvIlian Internees 1S1t stated that the men ~ere being Well cared for by Hung~nan doctors, and r;, N O. 12 WASHINGTON, D. C. DECEMBER 1944 tha.t they were entIrely satisfied Witht "_'-------------------------------------------- theIr treatment. They were sChed' j uled to be transferred ·to camps in Germany as soon as they had reo covered from their wounds. Un. The 1944 Christmas Package wounded aviators bpought down Nuts, mixed ___________ _________ · %, lb. over Hungary had been moved hristmas Package No. 2, packed are now held. The aim, of course, was Bouillon cubes __________________ 12 promptly to German camps. women volunteers in the Phila· to avoid railroad transport in Ger Fruit bars-________ ____________ _· 2 A later report by cable stated hia Center during the hottest many as much as possible. Dates ____ ___ __ _________ ______ __14 oz. that several Lazaretts in Hungary , of . the summ~r, r ~ ached G ~r Much thought was given to plan Cherries, canned__ ___ __ __ _____ ___ . 6 oz. containing in all about 60 wounded Y. VIa Sweden. -

EVADERS and PRISONERS 1941-42 to Be Led Straight to the Police Station by the German Who Had Thought He Was Saying "Deutsche?" and Wished to Surrender

CHAPTER 1 9 EVADERS AND PRISONER S O aircrew flying from English or Middle East bases the possibilit y T of falling into enemy hands was a continual danger. After 1940 , with air operations conducted principally over areas held by Germany an d Italy, every flight contained the seed of disaster, whether from enemy gun or fighter defences, adverse meteorological conditions, human erro r in navigation or airmanship, mechanical failure, or petrol shortage. Fre- quently, in dire straits, a captain of aircraft was forced to make the har d choice of ordering his crew to parachute into enemy territory or o f attempting to struggle back to base with the last and vital part of th e journey necessarily over the unrelenting sea . It is a measure of the resolution of British airmen that where any slim possibility existed the harder choice was taken, even though very frequently it ended in failure. Pilot Officer R. H. Middleton, Flight Sergeant A. McK. McDonald, Flying Officer A . W. R. Triggs and many others brought their crew s safely back to fight again by renouncing immediate safety at - the cost of freedom, but many Australians, in common with comrades of other Allied nations, perished in attempting the same achievement . Even though forced to abandon their aircraft over hostile territory , airmen were still not without hope if they reached the ground uninjured . The vast majority of R .A.A.F. men serving in England between 194 1 and 1945 operated with Bomber Command on night-bombing sorties , and when an aircraft was set afire, or exploded, or became uncontrollable a varying degree of opportunity was afforded for crew members to escape from their doomed aircraft. -

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of An

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of an Oral History Interview with FREDERICK M. WALD Aerial Gunner, Air Force, World War II and Career. 1996 OH 252 1 OH 252 Wald, Frederick M., (1921-2008). Oral History Interview, 1996. User Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 65 min.), analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Master Copy: 2 sound cassette (ca. 65 min.), analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Transcript: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Military Papers: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Abstract: Frederick M. Wald, a Marinette, Wisconsin native, discusses his career in the Air Force, including being held as a German prisoner of War during World War II. Wald talks about enlisting in the Air Corps in 1941 and being based at Tyndall Field (Florida) when the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred. He mentions being rejected for pilot and glider training, graduating from gunnery school and aerial gunners’ armament school, and having repeated complications with outdated medical records. In Boise (Idaho), Wald discusses forming a flight crew, flying a B-24 to Europe, and assignment to the 392 nd Bomb Group, 578 th Bomb Squadron, 8 th Air Force based in Wendling (England). He details being shot down on his second mission: losing three of four engines, the failure of the bailout alarm, and having no memory of his jump. After regaining consciousness in a French farmhouse, he talks about being sheltered by the French resistance for two weeks before being captured by the Gestapo. Wald talks being moved from the jail in Rouen to Luftwaffe headquarters in Paris, staying in the Rennes prison, and being held in solitary confinement in Frankfurt (Germany). -

Middle School History & Politics Society July 2020

MIDDLE SCHOOL HISTORY & POLITICS SOCIETY JULY 2020 PUBLICATION 1 Counter Arguments To Capitalism By Johnnie Willis-Bund In the following article I will not be directly attacking capitalism, however I will instead addressing arguments often made in capitalism’s favour (and hopefully showing that they hold very little water). I hope you find them interesting, and perhaps change your mind about the economic system you live under. The first and most common argument for capitalism is also, I find, one of the weakest. It starts of, as most capitalist arguments do. “Oh sure, communism’s a nice idea, BUT…” and then goes on like, “no one would have any incentive to work. The free market means your actions have consequences so you have to work hard.” This is a perversion of the truth. It’s the reverse of the truth. In fact, under capitalism, people have less of an incentive to work, because their labour is alienated. This means, because the means of production are privately owned (and not by the workers who actually use them) the work you do nd the profits of your labour get stolen by your boss. The very concept of profit itself depends on the fact that the labourers are underpaid. Don’t you think that this alienation may disincentivize workers and that they would be more inclined to work hard if they were able to claim the values of their own labour (by owning the means of production). What capitalism does is exploits people into doing work for other people and never receiving the value of their labours because they have been coerced into becoming another cog in the machine of surplus value theft because they would starve otherwise. -

1971-05-23 University of Notre Dame Commencement Program

One Hundred and Twenty-Sixth Commencement . Exercises OFFICIAL MAY ExERCISEs THE UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME NoTRE DAME, INDIANA THE GRADUATE ScHooL THE LAw ScHooL THE CoLLEGE OF ARTs AND LETTERS THE CoLLEGE OF SciENCE THE CoLLEGE OF ENGINEERING The Graduate and Undergraduate _Divisions of THE CoLLEGE OF BusiNEss ADMINISTRATION Athletic and Convocation Center At 2:00p.m. (Eastern Standard Time) Sunday, May 23, 1971 PROGRAM 0000 PRocEssiONAL CITATIONS FOR HoNORARY DEGREES by the Reverend James T. Burtchaell, C.S.C., S.S.L., Ph.D. Provost of the University THE CoNFERRING OF HoNORARY DEGREES by the Reverend Theodore -M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., S.T.D. President of the University PRESENTATION OF CANDIDATES FOR DEGREES by the Reverend Paul E. Beichner, C.S.C., Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School by Edward J. Murphy, J.D. Acting Dean of the Law School by Frederick J. Crosson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Letters by Bernard Waldman, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Science by Joseph C. Hogan, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Engineering by Thomas T. Murphy, M.C.S. Dean of the College of Business Administration THE CoNFERRING oF DEGREES by the Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., S.T.D. President of the University PREsENTATION OF THE FAcULTY AwARD PRESENTATION OF THE PROFESSOR THOMAS MADDEN FACULTY AwARD PREsENTATION OF THE PREsiDENT's AwARDS CoMMENCEMENT ADDRESS by Dr. Kenneth Keniston Yale Me_dical School New Haven, Connecticut SENIOR CLASS PRESIDENT'S ADDRESS by James J. D'Aurora CHARGE TO THE CLASS by the Reverend Theodore M. -

Prison Breaks 3

PRISON BREAKS 3 The larger than life story of Mark DeFriest, an infamous prison escape artist - the "Houdini of Florida" - whose notoriety and struggle with mental illness threaten his quest to be freed after 31 years behind bars. Animation from the Florida State Hospital escape sequence Mark DeFriest's life is living history. At age 19, his original sentence was for a nonviolent property crime, but because of additional punishment for escapes, he has spent his entire adult life behind bars. DeFriest has survived 31 years in prison, most of it in longterm solitary confinement in a custom cell above the electric chair at Florida State Prison. He has been raped, beaten, shot and basically left for dead, but he has somehow lived to tell the tale. When he was sent to prison in 1981, five out of six doctors declared that he was mentally incompetent to be sentenced. They warned the judges that Mark couldn't learn better behavior and needed treatment. Instead, he was allowed to plead guilty, even at one point to a Life Sentence. The documentary brings this story to life. True to the psychiatrists' expectations, Mark has amassed an astonishing number of disciplinary reports in prison for things like possession of escape paraphernalia, but also for behavioral violations like telling the guards his name was James Bond. "He's a little bit crazy, a little bit manipulative, but not really a bad person", as his former lawyer puts it. Apparently that point was lost on the system, as Mark has always been held with the worst of the worst. -

Squadron Leader Roger Bushell – 601 Squadron

Profile – Squadron Leader Roger Bushell – 601 Squadron. (From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia) 30 August 1910 – 29 March 1944 (aged 33) Left - Bushell in RAF uniform just before his capture. Right – Bushell having a laugh (permission to use pic kindly given by 601 Sqn web site) Place of Birth; Springs, Transvaal, South Africa Place of Death; Saarbrücken, Germany Years of Service; 1932-1944 Rank; Squadron Leader Commands held; No. 92 Squadron RAF (1939-1940) Squadron Leader Roger Joyce Bushell RAF (30 August 1910 – 29 March 1944) was a South Africa born British Auxiliary Air Force pilot who organised and led the famous escape from the Nazi prisoner of war camp, Stalag Luft III. He was a victim of the Stalag Luft III murders. The escape was used as the basis for the film The Great Escape. The character played by Richard Attenborough, Roger Bartlett, is modelled on Roger Bushell. Birth and early life Bushell was born in Springs, Transvaal, South Africa on 30 August 1910 to English parents Benjamin Daniel and Dorothy Wingate Bushell (nee White). His father, a mining engineer, had emigrated to the country from England and he used his wealth to ensure that Roger received a first class education. He was first schooled in Johannesburg, then aged 14 went to Wellington College in Berkshire, England. In 1929, Bushell matriculated to Pembroke College, Cambridge to read law. Bushell was keen to pursue non-academic interests from an early age. Roger Bushell excelled in athletics and represented Cambridge in skiing. Skiing One of Bushell's passions and talents was skiing: in the early 1930s he was declared the fastest Briton in the male downhill category. -

Stefan Geck, Dulag Luft/Auswertestelle West

Francia-Recensio 2009/4 19./20. Jahrhundert – Histoire contemporaine Stefan Geck, Dulag Luft/Auswertestelle West. Vernehmungslager der Luftwaffe für westalliierte Kriegsgefangene im Zweiten Weltkrieg, Frankfurt a. M., Berlin, Bern (Peter Lang) 2008, XX–544 p. (Europäische Hochschulschriften. Reihe 3: Geschichte und ihre Hilfswissenschaften, 1057). ISBN 978-3-631-57791-2, EUR 86,00. rezensiert von/compte rendu rédigé par Simon Paul Mackenzie, Columbia Over the past six decades a large number of memoirs written by ex-airmen held in the prisoner of war camps run by the Luftwaffe during the Second World War have been published in English, the majority focusing on escape attempts from places such as Stalag Luft III at Sagan. These memoirs, along with unpublished accounts, have been the primary source base for much of the secondary literature on the subject, particularly – though not exclusively – in English. The view from inside the wire, however, tells only part of the story. Though the record remains incomplete, as a number of scholars based in Austria, Canada and Germany have demonstrated both individually and collectively, there are now enough extant documents and other primary-source materials to reconstruct camp histories from the perspective of the captors instead of just the captives. Stefan Geck certainly proves this to be the case with respect to the Luftwaffe facilities handling intelligence gathering among newly captured Allied airmen, the story of which – especially given current debates about techniques and the laws of war – possesses a lot of contemporary resonance. The recollections of Royal Air Force and United States Army Air Force aircrew members who fell into German hands invariably at least touch on their experience at the hands of Luftwaffe interrogators; yet aside from a few references here and there, the system within which the interrogators operated has remained largely unexamined by scholars of the Second World War. -

The Excavation of WWII RAF Bomber, Halifax LV881-ZA-V

Pre-print - For the Journal of Conflict Archaeology (2018) The Excavation of WWII RAF Bomber, Halifax LV881-ZA-V PHIL MARTERa, RONALD VISSERb, PIM ALDERSc, CHRISTOPH RÖDERd, MICHAEL GOTTWALDe, MIRKO MANKf, STEVEN HUBBARDg, UDO RECKERh aDepartment of Archaeology, University of Winchester, UK; bDepartment of Archaeology, Saxion University of Applied Sciences, Deventer, The Netherlands; chessenARCHÄOLOGIE , Wiesbaden, Germany; dIndependent Aviation Archaeologist, Flugzeugwrackmuseum, Ebsdorfergrund, Germany; eDirector of Archaeology of the Federal State of Hesse, Wiesbaden, Germany. ABSTRACT. This article outlines the preliminary results of archaeological fieldwork at the crash site of RAF Halifax bomber LV881-ZA-V and explores some of the challenges presented by the excavation of this military wartime crash site. The aircraft and her crew were shot down by a German night fighter in the early hours of March 31st 1944 during the infamous Nuremberg Raid. Four of her crew were killed and the remaining three were taken prisoner and later took part in the ‘Long March’. All three survived the war. An international team comprised of staff and students from Germany, the Netherlands, Finland and the UK explored what remained of the crash site, located on a hill outside the village of Steinheim, north east of Frankfurt in the German Federal State of Hesse. KEY WORDS: World War II, RAF, Bomber Command, Crash site, Aviation Archaeology, Halifax bomber. Introduction The village of Steinheim lies among the gently rolling hills of the Wetterau region, some 50 km north east of Frankfurt in the district of Gießen (see Figure 1a and 1b). The rural district of Gießen forms part of the German Federal State of Hesse, and was an area frequently over-flown by Allied bombers during World War II. -

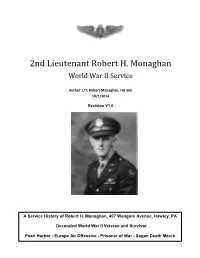

2Nd Lieutenant Robert H. Monaghan World War II Service

2nd Lieutenant Robert H. Monaghan World War II Service Author: LTC Robert Monaghan, His Son 10/1/2014 Revision V1.0 A Service History of Robert H. Monaghan, 407 Wangum Avenue, Hawley, PA Decorated World War II Veteran and Survivor Pearl Harbor - Europe Air Offensive - Prisoner of War - Sagan Death March 0 2nd Lieutenant Robert H. Monaghan World War II Military Service FOREWORD After our Mother died, we found a treasure trove of personal documents relating to our Father’s war time experiences. There were letters written home from pre-World War II, while he was stationed with the artillery in Hawaii, and after Pearl Harbor before he went to flight school. His US Army orders, Department of Defense notifications, Red Cross, magazines, newspaper clippings, POW documents, and other documents I found in my Mother’s papers enabled me to develop a narrative of his Army life. Letters written to his family also provide his view of the war while in the 306th Bomb Group and the boring life of a Prisoner of War in Stalag Luft III. Also included was a recipe list used to cook meals from various Red Cross rations for his combine. Most interesting was his diary detailing the Sagan Death March. While much has been written about the Death March, his papers reveal the daily experience from the Stalag Luft III evacuation to his arrival in Stalag Luft IIA in Southern Germany and subsequent rescue by General Patton’s Armored Division. By chance I located a member of his Stalag Luft III Combine Charles A. -

Four Months a Prisoner of War in 1945

State of Illinois Rod R. Blagojevich, Governor Illinois Department of Natural Resources Illinois State Geological Survey Four Months a Prisoner of War in 1945 Jack A. Simon Special Report 4 Front cover: Jack A. Simon, 1944. Released by the authority of the State of Illinois 0.3M - 2007 quadrennial meeting, held in the United States for the first time, brought more than 600 scientists from 25 foreign countries to Champaign-Urbana. Four Months a Prisoner of War In 1980, the Survey staff under Simon’s leadership observed the Survey’s 75th in 1945 Anniversary with a symposium, “Perspectives in Geology.” At that time, Simon noted the need for new studies applied to the broad spectrum of problems in waste disposal, new geologic criteria for location of oil and gas in the state, and coal Jack A. Simon conservation, recovery, and productivity. He also recognized the expanding role of geology in land-use planning because of greater needs for land-use planning, mining, and major energy and industrial plant siting. He realized that groundwa- ter availability would also command increased research, and he foresaw major advances in computerization of many kinds of geologic data and their application in research and service. In 1981, Simon suffered a severe stroke, and, although he made a rapid and remark- able recovery, he retired that year. He was a familiar figure at almost all Survey functions during his retirement years, and he was always greeted warmly by many staff who had worked for him. He was a kind and generous man, but his profound modesty prevented many from understanding the full measure of his service to his community.