Correspondence, Camaraderie, and Community: the Second World War for a Mother and Son

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aviation Classics Magazine

Avro Vulcan B2 XH558 taxies towards the camera in impressive style with a haze of hot exhaust fumes trailing behind it. Luigino Caliaro Contents 6 Delta delight! 8 Vulcan – the Roman god of fire and destruction! 10 Delta Design 12 Delta Aerodynamics 20 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan 62 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.6 Nos.1 and 2 64 RAF Scampton – The Vulcan Years 22 The ‘Baby Vulcans’ 70 Delta over the Ocean 26 The True Delta Ladies 72 Rolling! 32 Fifty years of ’558 74 Inside the Vulcan 40 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.3 78 XM594 delivery diary 42 Vulcan display 86 National Cold War Exhibition 49 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.4 88 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.7 52 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.5 90 The Council Skip! 53 Skybolt 94 Vulcan Furnace 54 From wood and fabric to the V-bomber 98 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.8 4 aviationclassics.co.uk Left: Avro Vulcan B2 XH558 caught in some atmospheric lighting. Cover: XH558 banked to starboard above the clouds. Both John M Dibbs/Plane Picture Company Editor: Jarrod Cotter [email protected] Publisher: Dan Savage Contributors: Gary R Brown, Rick Coney, Luigino Caliaro, Martyn Chorlton, Juanita Franzi, Howard Heeley, Robert Owen, François Prins, JA ‘Robby’ Robinson, Clive Rowley. Designers: Charlotte Pearson, Justin Blackamore Reprographics: Michael Baumber Production manager: Craig Lamb [email protected] Divisional advertising manager: Tracey Glover-Brown [email protected] Advertising sales executive: Jamie Moulson [email protected] 01507 529465 Magazine sales manager: -

The Magazine of the Raf Yatesbury Association. Incorporating Raf Stations Cherhill, Compton Bassett, Townsend and Yatesbury

SEPTEMBER 2011 No 51 THE MAGAZINE OF THE RAF YATESBURY ASSOCIATION. INCORPORATING RAF STATIONS CHERHILL, COMPTON BASSETT, TOWNSEND AND YATESBURY The Seven Standards on Parade at our Remembrance Service See page 4 Photo by Gordon Chivers RAF YATESBURY ASSOCIATION Patron Air Marshal Sir Alec Morris KBE, CB. COMMITTEE Chairman & Rev. B.L. Morris, Canterbury Bells, Ansford Hill, Castle Cary, Honorary Chaplain Somerset. BA7 7JL. Tel: 01963 351154 email: [email protected] Vice-Chairman Ron Stempfer,24 Hazlemere Gardens, Worcester Park, Surrey, & Standard Bearer KT4 8AH Tel: 0208 3375401 email: [email protected] Honorary Secretary Mrs. Rosie Watt, 5 Heather Way, Calne, Wiltshire, SN11 0QR & Treasurer Tel: 01249 814754 Minutes Secretary Alan Trinder, 7 Manor Road, Wantage, Oxfordshire, OX12 8DP Tel: 01235 763940 Membership Phil Tomaselli, 146 Stockwood Lane, Bristol, BS14 8TA Secretary Tel: 01275 836795 Public Relations Tony Gernon, 35 Bransby Road, Chessington, Surrey, KT9 & Standard Bearer 2JZ Tel: 0208 2874610 SPARKS Editor Clive Simpson, 113 Daubeney Road, London, E5 0EG Tel: 02032 225322 email: [email protected] Cenotaph Co-ordinator David Clark, 35 Lampern Crescent, Billericay, Essex, CM12 0FE Tel: 01277 625448 Webmaster Bill Hauxwell, 18 Hollyhock Close, Kempshott, Basingstoke, & Archivist Hants, RG22 5RF Tel: 01256 472035 Member without Portfolio Albert Mundy, 33 Priory Way, Haywards Heath, West Sussex, RH16 3LS Tel: 01444 413448 LOCAL BRANCH REPRESENTATIVE Eastern Branch David Clark (See above for contact details) 2 www.rafyatesbury.webs.com FROM THE U/T EDITOR The U/T tag was to be removed but before it is I must confess that our Membership Secretary was contacted by a member who told him my number was unobtainable. -

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631 Call# Title Author Subject 000.1 WARBIRD MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD EDITORS OF AIR COMBAT MAG WAR MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD IN MAGAZINE FORM 000.10 FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM, THE THE FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM YEOVIL, ENGLAND 000.11 GUIDE TO OVER 900 AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS USA & BLAUGHER, MICHAEL A. EDITOR GUIDE TO AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS CANADA 24TH EDITION 000.2 Museum and Display Aircraft of the World Muth, Stephen Museums 000.3 AIRCRAFT ENGINES IN MUSEUMS AROUND THE US SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION LIST OF MUSEUMS THROUGH OUT THE WORLD WORLD AND PLANES IN THEIR COLLECTION OUT OF DATE 000.4 GREAT AIRCRAFT COLLECTIONS OF THE WORLD OGDEN, BOB MUSEUMS 000.5 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE LIST OF COLLECTIONS LOCATION AND AIRPLANES IN THE COLLECTIONS SOMEWHAT DATED 000.6 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE AVIATION MUSEUMS WORLD WIDE 000.7 NORTH AMERICAN AIRCRAFT MUSEUM GUIDE STONE, RONALD B. LIST AND INFORMATION FOR AVIATION MUSEUMS 000.8 AVIATION AND SPACE MUSEUMS OF AMERICA ALLEN, JON L. LISTS AVATION MUSEUMS IN THE US OUT OF DATE 000.9 MUSEUM AND DISPLAY AIRCRAFT OF THE UNITED ORRISS, BRUCE WM. GUIDE TO US AVIATION MUSEUM SOME STATES GOOD PHOTOS MUSEUMS 001.1L MILESTONES OF AVIATION GREENWOOD, JOHN T. EDITOR SMITHSONIAN AIRCRAFT 001.2.1 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE BRYAN, C.D.B. NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM COLLECTION 001.2.2 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE, SECOND BRYAN,C.D.B. MUSEUM AVIATION HISTORY REFERENCE EDITION Page 1 Call# Title Author Subject 001.3 ON MINIATURE WINGS MODEL AIRCRAFT OF THE DIETZ, THOMAS J. -

FLAG of BOTSWANA - a BRIEF HISTORY Where in the World

Part of the “History of National Flags” Series from Flagmakers FLAG OF BOTSWANA - A BRIEF HISTORY Where In The World Trivia You must be granted permission from the government to fly the flag. Technical Specification Adopted: 30th September 1966 Proportion: 2:3 Design: A light blue field with horizontal black stripe with white border. Colours: PMS – Blue: 284C Brief History On 31st of March 1885, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland established the Bechuanaland Protectorate when Boer freebooters threatened the people of Botswana. Rather than have a specific colonial flag the Union Jack of Great Britain and Ireland was flown. The Protectorate lasted until 1966 when Botswana became the independent country of the Republic of Botswana and gained its own flag. The flag is a blue field with horizontal black stripe with a white border. This design was specifically chosen to contrast with the flag of South African flag as the country was under apartheid and symbolises harmony and peace between black and European people. The Union Jack of Great Britain and Ireland The Flag of the Republic of Botswana (1885 to 1966) (1966 to Present Day) Coat of Arms of Botswana The Coat of Arms of Botswana were adopted in 1966 and features a shield with three cogwheels representing industry at the top, three waves representing water in the centre and a red bulls head representing cattle herding. At the sides of the shield are zebras; the right-hand zebra holds sorghum and the left hand zebra holds ivory. Underneath is the motto PULA that means ‘rain.’ The Standard of the President of Botswana The Standard of the President of Botswana takes the light blue field from the national flag with a white black-bordered circle with the Coat of Arms of Botswana in the centre. -

Military Aircraft Crash Sites in South-West Wales

MILITARY AIRCRAFT CRASH SITES IN SOUTH-WEST WALES Aircraft crashed on Borth beach, shown on RAF aerial photograph 1940 Prepared by Dyfed Archaeological Trust For Cadw DYFED ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST RHIF YR ADRODDIAD / REPORT NO. 2012/5 RHIF Y PROSIECT / PROJECT RECORD NO. 105344 DAT 115C Mawrth 2013 March 2013 MILITARY AIRCRAFT CRASH SITES IN SOUTH- WEST WALES Gan / By Felicity Sage, Marion Page & Alice Pyper Paratowyd yr adroddiad yma at ddefnydd y cwsmer yn unig. Ni dderbynnir cyfrifoldeb gan Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf am ei ddefnyddio gan unrhyw berson na phersonau eraill a fydd yn ei ddarllen neu ddibynnu ar y gwybodaeth y mae’n ei gynnwys The report has been prepared for the specific use of the client. Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited can accept no responsibility for its use by any other person or persons who may read it or rely on the information it contains. Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited Neuadd y Sir, Stryd Caerfyrddin, Llandeilo, Sir The Shire Hall, Carmarthen Street, Llandeilo, Gaerfyrddin SA19 6AF Carmarthenshire SA19 6AF Ffon: Ymholiadau Cyffredinol 01558 823121 Tel: General Enquiries 01558 823121 Adran Rheoli Treftadaeth 01558 823131 Heritage Management Section 01558 823131 Ffacs: 01558 823133 Fax: 01558 823133 Ebost: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Gwefan: www.archaeolegdyfed.org.uk Website: www.dyfedarchaeology.org.uk Cwmni cyfyngedig (1198990) ynghyd ag elusen gofrestredig (504616) yw’r Ymddiriedolaeth. The Trust is both a Limited Company (No. 1198990) and a Registered Charity (No. 504616) CADEIRYDD CHAIRMAN: Prof. B C Burnham. CYFARWYDDWR DIRECTOR: K MURPHY BA MIFA SUMMARY Discussions amongst the 20th century military structures working group identified a lack of information on military aircraft crash sites in Wales, and various threats had been identified to what is a vulnerable and significant body of evidence which affect all parts of Wales. -

Hark the Heraldry Angels Sing

The UK Linguistics Olympiad 2018 Round 2 Problem 1 Hark the Heraldry Angels Sing Heraldry is the study of rank and heraldic arms, and there is a part which looks particularly at the way that coats-of-arms and shields are put together. The language for describing arms is known as blazon and derives many of its terms from French. The aim of blazon is to describe heraldic arms unambiguously and as concisely as possible. On the next page are some blazon descriptions that correspond to the shields (escutcheons) A-L. However, the descriptions and the shields are not in the same order. 1. Quarterly 1 & 4 checky vert and argent 2 & 3 argent three gouttes gules two one 2. Azure a bend sinister argent in dexter chief four roundels sable 3. Per pale azure and gules on a chevron sable four roses argent a chief or 4. Per fess checky or and sable and azure overall a roundel counterchanged a bordure gules 5. Per chevron azure and vert overall a lozenge counterchanged in sinister chief a rose or 6. Quarterly azure and gules overall an escutcheon checky sable and argent 7. Vert on a fess sable three lozenges argent 8. Gules three annulets or one two impaling sable on a fess indented azure a rose argent 9. Argent a bend embattled between two lozenges sable 10. Per bend or and argent in sinister chief a cross crosslet sable 11. Gules a cross argent between four cross crosslets or on a chief sable three roses argent 12. Or three chevrons gules impaling or a cross gules on a bordure sable gouttes or On your answer sheet: (a) Match up the escutcheons A-L with their blazon descriptions. -

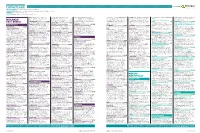

Contract Leads Powered by EARLY PLANNING Projects in Planning up to Detailed Plans Submitted

Contract Leads Powered by EARLY PLANNING Projects in planning up to detailed plans submitted. PLANS APPROVED Projects where the detailed plans have been approved but are still at pre-tender stage. TENDERS Projects that are at the tender stage CONTRACTS Approved projects at main contract awarded stage. Agent: Plan My Property, 1 Regent Street, Council of Kings Lynn & West Norfolk Norfolk Job: Detail Plans Granted for 4 Plans Granted for housing Client: Cambridge Ltd Agent: John Thompson & Partners Ltd, 17 Street, Skipton, North Yorkshire, BD23 1JR Tel: Fraisthorpe Wind Farm Limited, Willow Court, Finedon, Wellingborough, Northamptonshire, Developer: Trundley Design Services, Salgate houses Client: Mr. David Master Developer: City Council Agent: Cambridge City Council, - 23 Calton Road, Edinburgh, Lothian, EH8 01756 700364 West Way, Minns Business Park, Oxford, OX2 MIDLANDS/ NN9 5NB Tel: 01933 383604 Barn, Islington Road, Tilney All Saints, King’s Peter Humphrey Associates, 30 Old Market, The Guildhall, Market Square, Cambridge, CB2 8DL Contractor: Keepmoat Homes Ltd, Land Adjacent, Halton Moor Road 0JB Tel: 01865 261300 NOTTINGHAM £4.8M Lynn, Norfolk, PE34 4RY Tel: 01553 617700 Town Centre, Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, PE13 3QJ Contractor: Keepmoat Homes, 950 Regeneration House, Gorsey Lane, Coleshill, Halton £1m DURHAM £0.8M EAST ANGLIA Land South Of, Abbey Lane Aslockton LEICESTER £1.1M 1NB Tel: 01945 466966 Capability Green, Luton, Bedfordshire, LU1 Birmingham, West Midlands, B46 1JU Tel: Planning authority: Leeds Job: Outline Brancepeth -

Official Lineages, Volume 4: Operational Flying Squadrons

A-AD-267-000/AF-004 THE INSIGNIA AND LINEAGES OF THE CANADIAN FORCES Volume 4 OPERATIONAL FLYING SQUADRONS LES INSIGNES ET LIGNÉES DES FORCES CANADIENNES Tome 4 ESCADRONS AÉRIENS OPÉRATIONNELS A CANADIAN FORCES HERITAGE PUBLICATION UNE PUBLICATION DU PATRIMOINE DES FORCES CANADIENNES National Défense A-AD-267-000/AF-004 Defence nationale THE INSIGNIA AND LINEAGES OF THE CANADIAN FORCES VOLUME 4 - OPERATIONAL FLYING SQUADRONS (BILINGUAL) (Supersedes A-AD-267-000/AF-000 dated 1975-09-23) LES INSIGNES ET LIGNÉES DES FORCES CANADIENNES TOME 4 - ESCADRONS AÉRIENS OPÉRATIONNEL (BILINGUE) (Remplace l’ A-AD-267-000/AF-000 datée 1975-09-23) Issued on Authority of the Chief of the Defence Staff Publiée avec l'autorisation du Chef de l'état-major de la Défense OPI: DHH BPR : DHP 2000-04-05 A-AD-267-000/AF-004 LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES ÉTAT DES PAGES EN VIGUEUR Insert latest changed pages, dispose of superseded Insérer les pages le plus récemment modifiées et pages with applicable orders. disposer de celles qu'elles remplacent conformément aux instructions applicables. NOTE NOTA The portion of the text affected by the latest La partie du texte touchée par le plus récent change is indicated by a black vertical line in the modificatif est indiquée par une ligne verticale margin of the page. Changes to illustrations are dans la marge. Les modifications aux illustrations indicated by miniature pointing hands or black sont indiquées par des mains miniatures à l'index vertical lines. pointé ou des lignes verticales noires. Dates of issue for original and changes pages are: Les dates de publication pour les pages originales et les pages modifiées sont : Original/page originale ............0 ......... -

Royal Canadian Air Force's Managed Readiness Plan

Royal Canadian Air Force’s Managed Readiness Plan Major Marc-André La Haye JCSP 47 PCEMI 47 Master of Defence Studies Maîtrise en études de la défense Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and do Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs et not represent Department of National Defence or ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Ministère de Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used la Défense nationale ou des Forces canadiennes. Ce without written permission. papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par le Minister of National Defence, 2021. ministre de la Défense nationale, 2021. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE – COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 47 – PCEMI 47 2020 – 2021 MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES – MAÎTRISE EN ÉTUDES DE LA DÉFENSE ROYAL CANADIAN AIR FORCE MANAGED READINESS PLAN By Major M.A.J.Y. La Haye “This paper was written by a candidate « La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College in stagiaire du Collège des Forces canadiennes fulfilment of one of the requirements of the pour satisfaire à l'une des exigences du Course of Studies. The paper is a cours. L'étude est un document qui se scholastic document, and thus contains rapporte au cours et contient donc des faits facts and opinions which the author alone et des opinions que seul l'auteur considère considered appropriate and correct for appropriés et convenables au sujet. Elle ne the subject. -

1 Canadians in the Air, 1914–1919, 1939–1945

Canadians in the Air, 1914–1919, 1939–1945 Paul Goranson Anchoring the Kite cwm 19710261-3180 Beaverbrook Collection of War Art Canadian War Museum warmuseum.ca/learn Canadians in the Air 1 Canadians in the Air, 1914–1919, 1939–1945 Introduction Large-scale military aviation began with the First World War, not long after the 1909 flight of the Silver Dart marked the start of aviation in Canada. As no Canadian Air Force yet existed, thousands of Canadians fought the First World War in British flying units. Canadians first served with the Royal Flying Corps (rfc) or with the Royal Naval Air Service (rnas). These two services amalgamated on 1 April 1918 into the Royal Air Force (raf). In total, an estimated 13,000–22,000 individuals from Canada joined the British flying services. In 1924, the Royal Canadian Air Force (rcaf) was created. With the outbreak of war in September 1939, the rcaf was able to draw on an existing cadre of officers and airmen and also attracted experienced personnel from private enterprise. By 1945, close to 250,000 men and women had served in the rcaf at home and abroad. This guide will illustrate the process of researching an individual’s service, from the essential starting point of service documents to supporting resources for detail and further discovery. Helpful hint See lac’s Military Abbreviations used in Service Files page. warmuseum.ca/learn Canadians in the Air 2 Photo album of Flight Lieutenant William Burt Bickell, Royal Air Force cwm 19850379-001_p14 George Metcalf Archival Collection Canadian War Museum First World War, 1914–1919 While some recruitment and training were done Royal Flying Corps: For airmen who died or were in Canada, the flying services were British in discharged before 1 April 1918, their service records organization, administration, and operation. -

North Weald the North Weald Airfield History Series | Booklet 4

The Spirit of North Weald The North Weald Airfield History Series | Booklet 4 North Weald’s role during World War 2 Epping Forest District Council www.eppingforestdc.gov.uk North Weald Airfield Hawker Hurricane P2970 was flown by Geoffrey Page of 56 Squadron when he Airfield North Weald Museum was shot down into the Channel and badly burned on 12 August 1940. It was named ‘Little Willie’ and had a hand making a ‘V’ sign below the cockpit North Weald Airfield North Weald Museum North Weald at Badly damaged 151 Squadron Hurricane war 1939-45 A multinational effort led to the ultimate victory... On the day war was declared – 3 September 1939 – North Weald had two Hurricane squadrons on its strength. These were 56 and 151 Squadrons, 17 Squadron having departed for Debden the day before. They were joined by 604 (County of Middlesex) Squadron’s Blenheim IF twin engined fighters groundcrew) occurred during the four month period from which flew in from RAF Hendon to take up their war station. July to October 1940. North Weald was bombed four times On 6 September tragedy struck when what was thought and suffered heavy damage, with houses in the village being destroyed as well. The Station Operations Record Book for the end of October 1940 where the last entry at the bottom of the page starts to describe the surprise attack on the to be a raid was picked up by the local radar station at Airfield by a formation of Messerschmitt Bf109s, which resulted in one pilot, four ground crew and a civilian being killed Canewdon. -

Operation Freshie (1953)

Operation Freshie (1953) For most university students, “learning” means enrolling in a set number of courses each year and grinding your way through them until, in the fullness of time, you finally have your degree(s) in hand and are off to make the world a Better Place. In my day, the standard academic fare was, for some, complemented by military training programs sponsored by the three armed services. The Royal Canadian Air Force version was known as the University Reserve Training Plan (URTP), and its purpose was to stimulate interest in the Air Force and to ensure a flow of trained university students as commissioned officers for the Regular service or the Reserves. To deliver the program, provision was made in 1948 for the establishment of RCAF (Auxiliary) University Flights at all the major schools across the country. The University of Manitoba Flight was one of the first formed. After a few years, the Flights were elevated to Squadron status. The students’ training program covered three years. They attended lectures during the academic year, with pay, and could look forward to summer jobs as Flight Cadets while receiving flying or specialist training. For up to 22 weeks during three consecutive summers, they could be employed as pilot, navigator, or radio officer trainees, or in eleven non-flying specialist categories that ranged from aeronautical engineering to chaplaincy. Each University Flight/Squadron was to have an establishment of around 100 cadets, with selection being made at the rate of approximately 35 freshmen annually. At the University of Manitoba, a Tri-Service Day was instituted as part of Freshie Week that was laid on shortly after the school year began in September.