Studia Graeco-Arabica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Hal Victor Cardiff III 2015

Copyright by Hal Victor Cardiff III 2015 The Thesis Committee for Hal Victor Cardiff III Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Drinking with the Dead: Odyssean Nekuomanteia and Sympotic Sophrosyne in Classical Greek Vase Painting APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Nassos Papalexandrou Penelope Davies Drinking with the Dead: Odyssean Nekuomanteia and Sympotic Sophrosyne in Classical Greek Vase Painting by Hal Victor Cardiff III, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2015 Abstract Drinking with the Dead: Odyssean Nekuomanteia and Sympotic Sophrosyne in Classical Greek Vase Painting Hal Victor Cardiff III, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Nassos Papalexandrou Though the episode is well known from Book 11 of the Odyssey (11.23-330, 385- 567), only two painted vases survive from antiquity that clearly depict Odysseus' nekuomanteion ("consultation with the dead"): a mid-fifth century Attic pelike by the Lykaon Painter (Boston, MFA: 34.79), and an early-fourth century Lucanian kalyx-krater by the Dolon Painter (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale: 422). Owing to their rarity, these images have long interested scholars, but what has largely been missing from the discussion are attempts to situate the vase paintings of necromancy within a context of use. This thesis places these objects at their original functional context of the symposium, the ancient Greek, all-male drinking party. Following a hermeneutic method of analysis, I explore the ways in which ancient symposiasts might have looked at and understood the pictorial programs on these two objects as a reflection of their convivial activities and values. -

A History of Cynicism

A HISTORY OF CYNICISM Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com A HISTORY OF CYNICISM From Diogenes to the 6th Century A.D. by DONALD R. DUDLEY F,llow of St. John's College, Cambrid1e Htmy Fellow at Yale University firl mll METHUEN & CO. LTD. LONDON 36 Essex Street, Strand, W.C.2 Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com First published in 1937 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com PREFACE THE research of which this book is the outcome was mainly carried out at St. John's College, Cambridge, Yale University, and Edinburgh University. In the help so generously given to my work I have been no less fortunate than in the scenes in which it was pursued. I am much indebted for criticism and advice to Professor M. Rostovtseff and Professor E. R. Goodonough of Yale, to Professor A. E. Taylor of Edinburgh, to Professor F. M. Cornford of Cambridge, to Professor J. L. Stocks of Liverpool, and to Dr. W. H. Semple of Reading. I should also like to thank the electors of the Henry Fund for enabling me to visit the United States, and the College Council of St. John's for electing me to a Research Fellowship. Finally, to• the unfailing interest, advice and encouragement of Mr. M. P. Charlesworth of St. John's I owe an especial debt which I can hardly hope to repay. These acknowledgements do not exhaust the list of my obligations ; but I hope that other kindnesses have been acknowledged either in the text or privately. -

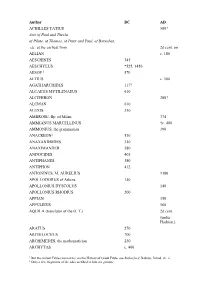

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

December 3, 1992 CHAPTER VIII

December 3, 1992 CHAPTER VIII: EARLY HELLENISTIC DYNAMISM, 323-146 Aye me, the pain and the grief of it! I have been sick of Love's quartan now a month and more. He's not so fair, I own, but all the ground his pretty foot covers is grace, and the smile of his face is very sweetness. 'Tis true the ague takes me now but day on day off, but soon there'll be no respite, no not for a wink of sleep. When we met yesterday he gave me a sidelong glance, afeared to look me in the face, and blushed crimson; at that, Love gripped my reins still the more, till I gat me wounded and heartsore home, there to arraign my soul at bar and hold with myself this parlance: "What wast after, doing so? whither away this fond folly? know'st thou not there's three gray hairs on thy brow? Be wise in time . (Theocritus, Idylls, XXX). Writers about pederasty, like writers about other aspects of ancient Greek culture, have tended to downplay the Hellenistic period as inferior. John Addington Symonds, adhering to the view of the great English historian of ancient Greece, George Grote, that the Hellenistic Age was decadent, ended his Problem in Greek Ethics with the loss of Greek freedom at Chaeronea: Philip of Macedon, when he pronounced the panegyric of the Sacred Band at Chaeronea, uttered the funeral oration of Greek love in its nobler forms. With the decay of military spirit and the loss of freedom, there was no sphere left for that type of comradeship which I attempted to describe in Section IV. -

Hippocrates in Context Studies in Ancient Medicine

HIPPOCRATES IN CONTEXT STUDIES IN ANCIENT MEDICINE EDITED BY JOHN SCARBOROUGH PHILIP J. VAN DER EIJK ANN HANSON NANCY SIRAISI VOLUME 31 HIPPOCRATES IN CONTEXT Papers read at the XIth International Hippocrates Colloquium University of Newcastle upon Tyne 27–31 August 2002 EDITED BY PHILIP J. VAN DER EIJK BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 Cover illustration: Late fifteenth-century portrait of Hippocrates sitting, reading. Behind him, two standing philosophers dispute (Wellcome Library, London). This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A C.I.P. record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISSN 0925–1421 ISBN 90 04 14430 7 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................ ix Acknowledgements ...................................................................... xiii Abbreviations ............................................................................. -

Logos in Greek Philosophy and Christian Thought

Durham E-Theses Ontologies of freedom and necessity: an investigation of the concepts of logos in Greek philosophy and Christian thought Cvetkovic, Vladimir How to cite: Cvetkovic, Vladimir (2001) Ontologies of freedom and necessity: an investigation of the concepts of logos in Greek philosophy and Christian thought, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4269/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ONTOLOGIES OF FREEDOM AND NECESSITY An Investigation of the concepts of logos in Greek philosophy and Christian thought Vladimir Cvetkovic Degree: MA The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published in any form, including Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent. All information derived from this thesis must be acknowledged appropriately. University of Durham Department of Theology 2001. -

In Season and out of Season': 2 Timothy 4:2 Abraham J

JBL 103/2 (1984) 235-243 IN SEASON AND OUT OF SEASON': 2 TIMOTHY 4:2 ABRAHAM J. MALHERBE Yale Divinity School, New Haven, CT 06510 Insufficient attention has been paid to what turns out to be a remark able admonition to Timothy: ". preach the word, be urgent in season and out of season (epistêthi eukairös akairös), convince, rebuke and exhort, be unfailing in patience and in teaching." Because epistêthi has no object, the relation of the admonition to the rest of the sentence is unclear,1 but it seems natural to take it as pointing to the preceding keryxon.2. Understood thus, Timothy is commanded to have "an attitude of prompt attention that may at any moment pass into action/'3 Eukairös akairös is an oxymoron and is "made still more emphatic by the omission of the copula."4 It has sounded proverbial to some com mentators,5 and C. Spicq has pointed out that eukairia is a rhetor ical term.6 Exegetes have primarily been interested in the person or persons to whom the preaching should be opportune or inopporune. Some have held that the reference is to Timothy,7 others to Timothy's 1 Some commentators do not discuss the relationship to the rest of the sentence or are themselves unclear on how they understand it, e.g., W. Lock, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Pastoral Epistles (ICC; New York: Scribner, 1924); Ε. K. Simpson, The Pastoral Epistles (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1954) 152; J. Jeremías, Die Briefe an Timo- theus und Titus (NTD; Göttingen: Vandenhœck und Ruprecht, 1963) 56; M. -

The Stromata, Or Miscellanies

The Stromata, or Miscellanies THE STROMATA, OR MISCELLANIES 299 638 Book I Book I 639 Chapter I.—Preface—The Author’s Object—The Utility of Written Compositi… 951 CHAPTER I.—PREFACE—THE AUTHOR’S OBJECT—THE UTILITY OF WRITTEN COMPOSITIONS. [Wants the beginning] . that you may read them under your hand, and may be able to preserve them. Whether written compositions are not to be left behind at all; or if they are, by whom? And if the former, what need there is for written compositions? and if the latter, is the composition of them to be assigned to earnest men, or the opposite? It were certainly ridiculous for one to disapprove of the writing of earnest men, and approve of those, who are not such, engaging in the work of composition. Theopompus and Timæus, who composed fables and slanders, and Epicurus the leader of atheism, and Hipponax and Archilochus, are to be allowed to write in their own shameful manner. But he who proclaims the truth is to be prevented from leaving behind him what is to benefit posterity. It is a good thing, I reckon, to leave to posterity good children. This is the case with children of our bodies. But words are the progeny of the soul. Hence we call those who have instructed us, fathers. Wisdom is a communicative and philanthropic thing. Accordingly, Solomon says, “My son, if thou receive the saying of my commandment, and hide it with thee, thine ear shall hear wisdom.”952 He points out that the word that is sown is hidden in the soul of the learner, as in the earth, and this is spiritual planting. -

Masters, Pupils and Multiple Images in Greek Red-Figure Vase Painting

MASTERS, PUPILS AND MULTIPLE IMAGES IN GREEK RED-FIGURE VASE PAINTING DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Sue Allen Hoyt, B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Mark D. Fullerton, Adviser Professor Timothy J. McNiven __________________________ Adviser Professor Howard Crane History of Art Graduate Program Text copyright by Sue Allen Hoyt 2006 ABSTRACT Little is known about Athenian vase-painting workshops of the 6th through 4th centuries BC. Almost no references exist in ancient literature, and there are few archaeological remains besides the vases themselves. I examined the technical details of vase-painting “copies”–images of uncommon scenes on vases by painted different painters– and compared the steps in the painting process, (especially the preliminary sketches), to see if these could supply any information about workshop practices. The research revealed that there are differences in sketches executed by different painters, and that there were often obvious differences in the care exercised in the different steps of the painting process. When the different steps consistently exhibit different levels of skill in execution, this suggests that workshops were organized so that workers with few skills performed the tasks that demanded the least; more-skilled workers painted the less-important borders etc., and the most-advanced painted the figures. On a few vases the sketch lines were more skillfully executed than the paintings that overlay them. Further, in the case of the Marsyas Painter and the Painter of Athens 1472, more than one pair of vases with replicated rare scenes ii exists. -

The Persian Bird's Conquest

Cahn’s Quarterly 1/2020 Recipe from Antiquity The Persian Bird’s Conquest By Yvonne Yiu bustle that ensues following his cry: “When he sings his song of dawning everybody jumps out of bed – smiths, potters, tanners, cobblers, bathmen, corn-dealers, lyre-turning shield-makers; the men put on their shoes and go out to work although it is not yet light.” (Arist., Birds 488-92). Furthermore, cocks fulfilled a number of symbolic and ritual functions, for instance as sacrificial an- imals or as love tokens from the adult male (erastes) to the younger male (eromenos). Not least, cockfighting was a very popular sport. However, the “Persian bird’s" actual con- quest, which enabled it to become the most common bird in the world with a current population estimated at around 23 billion by the FAO, paradoxically did not begin until it found a place on the dinner menu. It is difficult to determine when, exactly, Picentine bread and sala cattabia Apiciana on A PLATE. Clay. Dm. 26 cm. Roman, 3rd-5th cent. A.D. CHF 3,200. A GRATER. Bronze. L. 14 cm. Etruscan, 5th-3rd cent. B.C. CHF 1,800. A KNIFE. Bronze, iron. L. 14.7 cm. Roman, chicken eggs and meat became a significant 1st-3rd cent. A.D. CHF 1,800. A SPOON. Silver. L. 9.5 cm. Roman, 2nd-4th cent. A.D. CHF 2,800. nutritional factor in the Mediterranean. An- drew Dalby assumes that in the course of “Those were terrible times for the Athenians. native to Southeast Asia. The earliest conclu- the Classical Period chickens rapidly sup- The fleet had been lost in the Sicilian Expe- sive evidence of domestication comes from planted the less productive goose, which dition, Lamachos was no longer, Nikias was the Bronze Age Indus Culture and dates from had been the farmyard egg-layer in Greece dead, the Lacedaemonians besieged Attica," ca. -

The Double Axe and Approaching the Question of Karian-Kretan Interaction

Karia and Krete: a study in social and cultural interaction Naomi H Carless Unwin UCL DPhil History 1 I, Naomi H Carless Unwin, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract My thesis focuses on social and cultural interaction between Karia (in south western Anatolia) and Krete, over a long time span; from the Bronze Age to the Roman period. A persistent tradition existed in antiquity linking the Karians with Krete; this was mirrored in civic mythologies in Karia, as well as in cults and toponyms. My research aims to construct a new framework in which to read these traditions. The way in which a community ‘remembered’ its past was not an objective view of history; traditions were transmitted because they were considered to reflect something about a society. The persistence of a Kretan link within Karian mythologies and cults indicates that Krete was ‘good to think with’ even (or especially) during a period when Karia itself was undergoing changes (becoming, in a sense, both ‘de-Karianized’ and ‘Hellenized’). I focus on the late Classical and Hellenistic periods, from which most of our source material derives. The relevance of a shared past is considered in light of actual contacts between the two regions: diplomatic, economic, cultural and military. Against the prevailing orthodoxy, which maintains that traditions of earlier contacts, affinities and kinship between peoples from different parts of the Mediterranean were largely constructs of later periods, I take seriously the origins of such traditions and explore how the networks that linked Minoan Krete with Anatolia could have left a residuum in later conceptualisations of regional history. -

Representations of Truth and Falsehood in Hellenistic Poetry

Representations of Truth and Falsehood in Hellenistic Poetry A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of Classics Of the College of Arts and Sciences by Kathleen Kidder B.A. University of Texas at Austin February 2018 Committee Chair: Kathryn J. Gutzwiller, Ph.D. Abstract This dissertation examines how five Hellenistic poets represent the processes of evaluating truth and falsehood. Applying the philosophic concept of a criterion of truth, I demonstrate that each poetic persona interrogates truth by suggesting a different kind of criterion. Due to the indebtedness of Hellenistic poetry to previous literature, the second chapter summarizes the evolution of pertinent vocabulary for truth and falsehood, tracking the words’ first appearances in early poetry to their reappearance in Hellenistic verse. In my third chapter, I discuss notions concerning the relationship between truth and poetry throughout Greek literary history. The fourth chapter covers Aratus’ Phaenomena and Nicander’s Theriaca, two poems containing scientific subject matter framed as true. Yet, as I argue, the poems’ contrasting treatments of myths attest to the differences in the knowability of the respective material. In the Phaemomena, a poem about visible signs, Aratus’ myths offer a model for interpreting an ordered Stoic universe via regular and perceptible signs. By contrast, Nicander’s myths replicate the uncertainty of his subject matter (deadly creatures and remedies) and the necessity of direct experience as a criterion. The dichotomy between certainty and uncertainty applies also to the fifth chapter, which analyzes the narratorial voices of Callimachus in the Aetia and Apollonius of Rhodes in the Argonautica.