Viral and Sheep-Ish Encounters with Fashion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Academy Journal

The A cademy Journal Lawrence Academ y/Fall 2012 IN THIS EDITION COMMENCEMENT 28 – 32 REUNION WEEKEND 35 – 39 ANNUAL REPORT 52 – 69 The best moments in my life in schools (and perhaps of life in First Word general) have contained a particular manner of energy. As I scan my past, certain images and sensations light up the sensors with by Dan Scheibe, Head of School an unusual intensity. I remember a day during my junior year in These truly “First Words” gravitate around the following high school when I was returning to my room after class on a particular and powerful forces: the beginning of the school year, bright but otherwise unspectacular day in the fall. The post-lunch the beginning of another chapter in Lawrence Academy’s rich glucose plunge was looming, but still, I acutely remember an history, and (obviously) the beginning of my tenure as head of unusual bounce in my stride as I approached my room on “The school. I draw both strength and conviction from the energies Plateau” (a grandiose name for the attic above the theater where associated with such beginnings. The auspicious nature of the they housed a small collection of altitude-tolerant boarders). moment makes it impossible to resist some enthusiastic The distinct physical sensations of lightness were accompanied introductory contemplations. by emotional sensations of delight not usually associated with Trustees of Lawrence Trustees with 25 or More Academy Years of Service Editors and Contributors Bruce M. MacNeil ’70, President 1793 –1827 Rev. Daniel Chaplin (34) Dave Casanave, Lucy C. Abisalih ’76, Vice President 1793 –1820 Rev. -

Cultural Translations and East Asian Perspectives1 Sarah Cheang and Elizabeth Kramer

Fashion and East Asia: Cultural Translations and East Asian Perspectives1 Sarah Cheang and Elizabeth Kramer Introduction Fashion speaks to communities across borders, involving inter-lingual processes and translations across cultures, media, and sectors. This special issue explores East Asian fashion as a multifaceted process of cultural translation. Contributions to this special issue are drawn from the AHRC funded network project, ‘Fashion and Translation: Britain, Japan, China and Korea’ (2014-15)2, and the following articles investigate the role of clothing fashions as a powerful and pervasive cultural intermediary within East Asia as well as between East Asian and European cultures. Thinking about East Asia through transnational fashion allows us to analyze creative and cultural distinctiveness in relation to imitation, transformation and exchange, and to look for dialogues, rather than oppositions, between the global and the local. This approach is not only useful but also essential in a world that has been connected by textile trading networks for millennia, and yet feels increasingly characterized by the transnational and by globalized communication. As Sam Maher has asserted, ‘Few industries weave together the lives of people from all corners of the globe to quite the extent that the textile and garment industries do’ (2015-16: 11). The planet is connected through everyday clothing choices, and for millions the industry also provides their livelihood. In her discussion of transcultural art, Julie Codell emphasizes that borders ‘are permeable and liminal, not restrictive spaces’ and that we can see in the production, consumption and reception of transcultural art the coexistence of diverse cultures expressed in ambiguous, discontinuous or new ways (2012: 7). -

![Debt Shall Be [$2099572950]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1965/debt-shall-be-2099572950-1531965.webp)

Debt Shall Be [$2099572950]

SESSION OF 1988 Act 1988-23 111 No. 1988-23 AN ACT SB 515 Amending the act of December 8, 1982 (P.L.848, No.235), entitled “An act pro- viding for the adoption of capital projects related to the repair, rehabilitation or replacement of highway bridges to be financed from current revenue or by the incurring of debt and capital projects related to highway and safety improvement projects to be financed from current revenue of the Motor License Fund,” further providing for or adding projectsin Allegheny County, Beaver County, Bedford County, Berks County, Blair County, Bradford County, Bucks County, Butler County, Cambria County, Cameron County, Centre County, Chester County, Clearfield County, Crawford County, Cum- berland County, Dauphin County, Delaware County, Elk County, Erie County, Forest County, Franklin County, Fulton County, Greene County, Huntingdon County, Indiana County, Jefferson County, Lackawanna County, Lancaster County, Lawrence County, Lebanon County, Lehigh County, Luzerne County, Lycoming County, McKean County, Mercer County, Mifflin County, Monroe County, Montgomery County, North- ampton County, Northumberland County, Perry County, Philadelphia County, Pike County, Potter County, Schuylkill County, Snyder County, Somerset County, Susquehanna County, Tioga County, Venango County, Warren County, Washington County, Wayne County, Westmoreland County and Wyoming County; and making mathematicalcorrections. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania hereby enacts as follows: Section 1. Section 2 of the act of December 8, 1982 (P.L.848, No.235), known as the Highway-Railroad and Highway Bridge Capital Budget Act for 1982-1983, amended July 9, 1986 (P.L.597, No.100), is amended toread: Section 2. Total authorization for bridge projects. -

Bike Boom: the Unexpected Resurgence of Cycling, 217 DOI 10.5822/ 978-1-61091-817-6, © 2017 Carlton Reid

Acknowledgments Thanks to all at Island Press, including but not only Heather Boyer and Mike Fleming. For their patience, thanks are due to the loves of my life—my wife, Jude, and my children, Josh, Hanna, and Ellie Reid. Thanks also to my Kickstarter backers, listed overleaf. As much of this book is based on original research, it has involved wading through personal papers and dusty archives. Librarians in America and the UK proved to be exceptionally helpful. It was wonderful—albeit distracting— to work in such gob-stoppingly beautiful libraries such as the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, and the library at the Royal Automobile Club in London. I paid numerous (fruitful) visits to the National Cycling Archive at the Modern Records Centre at Warwick University, and while this doesn’t have the architectural splendor of the former libraries, it more than made up for it in the wonderful array of records deposited by the Cyclists’ Touring Club and other bodies. I also looked at Ministry of Transport papers held in The National Archives in Kew, London (which is the most technologically advanced archive I have ever visited, but the concrete building leaves a lot to be desired). Portions of chapters 1 and 6 were previously published in Roads Were Not Built for Cars (Carlton Reid, Island Press, 2015). However, I have expanded the content, including adding more period sources. Carlton Reid, Bike Boom: The Unexpected Resurgence of Cycling, 217 DOI 10.5822/ 978-1-61091-817-6, © 2017 Carlton Reid. Kickstarter Backers Philip Bowman Robin Holloway -

The Journal Journal

The Journal of the International Veteran Cycle Association Issue No. 52 March 2014 For more information see pages 23, 24 in this Journal or email [email protected] Contents President’s message…………..page 3 Le mot du President…………..page 3 Bericht des Prasedente…….....Seite 4 Items of Interest………………......5-7 Points d'intérêt …………………..5-7 Interessante Artikel ……….…….5-7 New books……………………....8-10 Nouveaux livres ………………...8-10 Neue Bücher …………..……….8-10 Reports of events…………..…..11-17 Rapport………………...………11-17 Berichte ……………...………..11-17 Calendar of events………….….18-23 Calendrier des événements ..…..18-23 Veranstaltungskalender ……….18-23 Next Rally 2014 in Hungary..…24-25 Rallye 2014 en Hongrie …….…24-25 Nächste Rallye in Ungarn …….24-25 Advertisements………………..25-26 Annonces ……………………...25-26 Werbung ………………...…….25-26 The International Veteran Cycle ASSOCIATION The International Veteran Cycle Association (IVCA) is an association of organizations and individuals interested in vintage bicycles: riding, collecting, restoration, history and their role in society. Statement of Purpose The International Veteran Cycle Association is dedicated to the preservation of the history of the bicycle and bicycling and the enjoyment of the bicycle as a machine. On 26th May 1986, at Lincoln ,UK, the International Veteran Cycle Association (IVCA in short) was formed by Veteran Cycle Clubs, Museums and Collectors of old pedal cycles and related objects from various countries. The Objectives of the Association are: To encourage interests and activities relating to all old human-powered vehicles of one or more wheels deriving from the velocipede tradition. To support and encourage research and classification of their history and to act as a communication medium between clubs, societies and museums world-wide on mutual matters relating to old cycles. -

Professional Engineers

PROFESSIONAL ENGINEERS Abadie, Randall James 10756 Abernathy, Calvin Glen 10339 Abu-Yasein, Omar Ali 16397 Adams, Bruce Harold 08468 Shell Explor & Prod. Co. Cook Coggin Engrs., Inc. A & A Engineering URS Corporation Sr Staff Civil Engr Engineer President/Sr. Engr. Vice President PO Box 61933 Cook Coggin Engrs., Inc. 5911 Renaissance Place 1621 Audubon Street New Orleans, LA 70161 703 Crossover Road Suite B New Orleans, LA 70118-5501 (504)728-4755 Tupelo, MS 38802 Toledo, OH 43623 (504)837-6326 (662)842-7381 (419)292-1983 Abbas, Michael Dean 19060 Adams, Gary Robert 17933 Atlas Engineering, Inc. Abesingha, Chandra 17493 Abughazleh, Qasem 15842 Adams Consulting Engrs Principal Struct Eng Padminie Mohammad Executive VP 7944 Grow Lane Civil Eng. Associates,Inc URS Corporation 910 S. Kimball Ave. Houston, TX 77040 President Sr. Bridge Engr. Southlake, TX 76092 (713)939-4995 4028 Lambert Trail 307 W. Gatehouse Dr. #E (817)328-3200 Birmingham, AL 35242 Metairie, LA 70001 Abbate, Martin Anthony 10816 (205)595-0401 (504)218-0866 Adams, James Curry 13032 URS Washington Division Tennessee Valley Authorit Mngr Electrical Abolhassani, Ali 16297 Achee Jr, Lloyd Joseph 05569 Manager 4060 Forest Run Circle Structural Concepts Engr. Achee Surv. & Engr. PLLC 2130 County Road 165 Medina, OH 44256 Dir. Of Engineering Owner Rogersville, AL 35652-9603 (216)523-3998 1200 N. Jefferson St. 1808 13th Street (256)386-3655 Suite F Pascagoula, MS 39567 Abbattista, Steven 14813 Anaheim, CA 92807 (228)762-5454 Adams, Jared J 19752 O'Dea, Lynch, Abbattista (714)632-7330 SidePlate Systems, Inc. Vice President Achord, Aaron Joseph 10160 Sr. -

Avoiding the Trick Keeping Pets Safe on What Can Be a Scary Holidayiday

DECORATIONS: Elaborated props spur good Halloween sales. | 2E The Paducah Sun Life| Sunday, October 23, 2011 | paducahsun.com Section E Avoiding the trick Keeping pets safe on what can be a scary holidayiday BY REBECCA FELDHAUSAUS [email protected] t’s diffi cult not to smile when you see a dogog dressed to the nines as a queen, a bumblebee or a mermaid.aid. It’s a festivefestive I holiday, so why not include the four-leggeded members ofof the family? Although it’s fun to dress man’s best friend upup forfor Halloween, local veterinarians suggest extra attention for petspets around the spooky holiday to avoid physical and mentaltal stress. Dr. Daniel Everett, local veterinarian, said therehere are several things pet owners should be aware of comecome Hal- loween. First is food. For some families, pets areare like their children; they want to treat them just like everyoneryone else. Pets should generally not receive any kind of candy,y, Everett said.said. “Dog treats are not made for kids and kid treatseats are not made for dogs,” Everett said simply. It doesn’t take sugary treats to cause upset stomachstomachs in pets, he said. Any change in diet can throw an animal’smal’s digestivedigestive system off, causing diarrhea and vomiting. One way to avoid dogs and cats getting into candy is to put the pets in interior rooms of the house, away fromrom windows, doors and the candy bowl. That way, pets can’tt get to the treats, and they aren’t outside to get any specialal treats fromfrom passersby. -

History and Temporal Tourism

"SO YOU WANT TO BE A RETRONAUT?”: HISTORY AND TEMPORAL TOURISM Tiffany L. Knoell A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2020 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kenneth Borland Graduate Faculty Representative Esther Clinton Thomas Edge © 2020 Tiffany L. Knoell All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor In “So You Want to Be A Retronaut?”: History and Temporal Tourism, I examine how contemporary individuals explore and engage with the past beyond the classroom through nostalgic consumerism, watching historical reality television, visiting historical sites or living history museums, handling historical objects, and, in many cases, participating in living history or historical re-enactment. The phrase “make America great again” taps directly into a belief that our nation has been diverted from a singular history that was better, purer, or even happier. What it ignores, though, is that the past is fraught for millions of Americans because their history – based on generations of inequality – is not to be celebrated, but rather commemorated for those who died, those who survived, and those who made their place in a nation that often didn’t want them. To connect to that complicated history, many of us seek to make that history personal and to see a reflection of who we are in the present in the mirror of past. For this project I conducted 54 interviews of subjects gathered from a variety of historically significant commemorations and locations such as the 2013 and 2015 memorial observances at Gettysburg, PA, and sites at Mount Vernon, Historic Jamestowne, and Colonial Williamsburg, VA. -

International Education Column 20191120

CHINA DAILY Wednesday, November 20, 2019 | 19 YOUTH A design piece by the “sustainability design award” Students take winner, Celine Zara Constantinides from the University of Huddersfield in the United a chic step on Kingdom. career path closing ceremony. A global fashion contest uncovers “One appealing aspect of this con future talent, Li Yingxue in Beijing test is that fashion and Xie Chuanjiao in Qingdao report. newcomers can have many opportu nities to communi ith the red orb of the trial networking, design shows, cate with industry sun spilling its light exhibitions, seminars, a fashion insiders,” says Guan. on the sea, spectators contest and an award ceremony. Zhu Shaofang, vice on Zhanqiao Pier, A team of 20 judges scored the president of the China Qingdao, W East China’s Shandong designers’ works under five key met Fashion Association, said province, were treated to a radiant rics: fashion, quality, market, tech She participated in the during the event that the fashion spectacular. nology and responsibility. The Tweed Run in London, an competition served as a The pier, a landmark tourist attrac judges talked to each designer to annual event in which platform to cultivate talent tion, was transformed by the bright better understand their design con cyclists ride through Lon in fashion, and she praised colors of the models’ outfits elegantly cepts. don in British tweeds that “the competition not displayed on the 440meterlong The young designers also show and brogues. only enables upand centuryold “runway”. cased their creations at an exhibi Guan says that, in coming young design The pier, once used as a navy dock tion at Qingdao Mixc, a popular her design, she tried ers to display their built in 1892 during the Qing Dynas shopping mall, and members of the to express her nos work and communi ty (16441911), was actually decreed public were asked to vote for their talgia for her col cate with each other, a national industrial heritage site in favorite designs. -

High Society

NO. 37 (1829) САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГ-ТАЙМС WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2014 WWW.SPTIMES.RU NIKOLAY SHESTAKOV SHESTAKOV NIKOLAY Inspired by the popular crime novels by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, over 300 people took part in the city’s annual Tweed Run on Sept. 13, dressed in their best Sherlock Holmes HIGH SOCIETY outfits and riding a 10-kilometer route throughout the city, the longest in the event’s history, before being rewarded with a traditional English-style picnic at the end. NATIONAL NEWS BUSINESS FOCUS Voting The Cosmo Effect ARTS & CULTURE Controversy Celebrating Queerfest Swedish rocker Jenny Wilson Nationwide elections steps up to front the annual overshadowed by scandals Russia’s leading magazine LGBT festival. Page 8. and violation reports. Page 3. celebrates 20 years. Page 5. LocalNews www.sptimes.ru | Wednesday, September 17, 2014 ❖ 2 Poltavchenko Win Marked by Controversy By Sergey Chernov gitimate — both by the way of selecting THE ST. PETERSBURG TIMES candidates and by the methods of voting Acting governor Georgy Poltavchenko and counting the votes,” the party said officially received a record-breaking 79.3 in a statement. percent of votes at in a controversial gu- Poltavchenko, who was appointed bernatorial election — the first since as the head of St. Petersburg by Presi- 2003 — in St. Petersburg on Sunday. dent Vladimir Putin in August 2011, Speaking on the city-sponsored De- stepped aside as governor to run in an mocracy Day outdoor pop concert on early gubernatorial election in June, Palace Square in the evening, Pol- but continued to perform his duties as tavchenko described the election as an acting governor. -

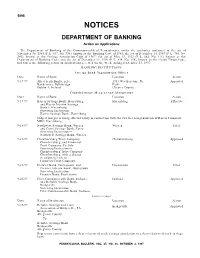

NOTICES DEPARTMENT of BANKING Action on Applications

5098 NOTICES DEPARTMENT OF BANKING Action on Applications The Department of Banking of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, under the authority contained in the act of November 30, 1965 (P. L. 847, No. 356), known as the Banking Code of 1965; the act of December 14, 1967 (P. L. 746, No. 345), known as the Savings Association Code of 1967; the act of May 15, 1933 (P. L. 565, No. 111), known as the Department of Banking Code; and the act of December 19, 1990 (P. L. 834, No. 198), known as the Credit Union Code, has taken the following action on applications received for the week ending September 23, 1997. BANKING INSTITUTIONS Foreign Bank Organization Offices Date Name of Bank Location Action 9-17-97 Allied Irish Banks, p.l.c. 1703 Weatherstone Dr. Approved Bankcentre, Ballsbridge Paoli Dublin 4, Ireland Chester County Consolidations, Mergers and Absorptions Date Name of Bank Location Action 9-17-97 Harris Savings Bank, Harrisburg, Harrisburg Effective and Harris Interim Savings Bank I, Harrisburg Surviving Institution— Harris Savings Bank, Harrisburg Subject merger is being effected solely in connection with the two-tier reorganization of Harris Financial, MHC, Harrisburg. 9-18-97 Northwest Savings Bank, Warren Warren Filed and Corry Savings Bank, Corry Surviving Institution— Northwest Savings Bank, Warren 9-18-97 Chambersburg Trust Company, Chambersburg Approved Chambersburg, and Financial Trust Company, Carlisle Surviving Institution— Chambersburg Trust Company Chambersburg, with a change in corporate title to Financial Trust Company 9-22-97 -

Football for a Cure Jay Verspeelt Citizen Staff Reporter

Turn To page 4 Turn To page 7 Turn To page 8 Volume VIII I ssue IV www .T he medIa plex .com ocTober 16, 2012 e h T CONVERGED CITIZEN The Inaugural Tweed Run Football for a cure Jay Verspeelt Citizen Staff Reporter The day before Thanksgiving saw the Inaugural Windsor Tweed Run, a city cycle ride begin - ning in Walkerville. About 30 people showed up for the the Inaugural Windsor Tweed Run, a riverfront cycle ride starting in Walkerville, ending in Sandwich town and finally returning to Walkerville. Participants wore outfits as if it were the turn of the 20th century Britain. All types of bikes were allowed, but classic bikes were encour - aged. The event was created over pints at the Kildare House by Windsor residents Stephen Hargreaves and Chris Holt. It was inspired by the London Photo by Jay Verspeelt Tweed Run which started in Photo by Marissa DeBortoli Sara Howie on her Linus bicy - 2009 as a bike across the city cle participating in the Ecole Secondaire l'Essor player Matt Marentette (4) runs with the ball while teammate It now includes 400 partici - Inaugural Windsor Tweed Run Mitch Diluca (80) blocks St Joseph's Catholic High School player Austin Cartier Oct. pants a year. in Walkerville Oct. 7. 4 . October is breast cancer awareness month and local football teams are campaign - Holt, a Ford tradesperson, is ing to raise money. Organized by Tami Hawkins, a teacher at Tecumseh Vista currently opening a bike shop along the way including the Academy, the event has been running for three years and donates all profits to the in Walkerville next to Jones & Manchester Pub, where partic - Windsor Regional Cancer Centre to improve patient care.