History and Temporal Tourism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Studies (FILM) 1

Film Studies (FILM) 1 FILM-115 World Cinema 3 Units FILM STUDIES (FILM) 54 hours lecture; 54 hours total This course will survey the historical, social, and artistic development FILM-100 Survey and Appreciation of Film 3 Units of cinema around the globe, introducing a range of international films, 54 hours lecture; 54 hours total movements, and traditions. This course is an introduction to the history and elements of filmmaking Transfers to both UC/CSU such as narrative, mise-en-scene, cinematography, acting, editing, and FILM-117 Director's Cinema 3 Units sound as well as approaches to film criticism. 54 hours lecture; 54 hours total Transfers to both UC/CSU This course examines the historical and artistic career of a seminal FILM-101 Introduction to Film Production 3 Units director in cinema history. Possible subjects include Martin Scorsese, 36 hours lecture; 54 hours lab; 90 hours total Alfred Hitchcock, Francis Ford Coppola, and Woody Allen. This course is designed to introduce you to the creative process Transfers to CSU only of filmmaking. We will study all aspects of production from the FILM-120 Horror Film 3 Units conceptualization of ideas and scripting, to the basic production 54 hours lecture; 54 hours total equipment and their functions, and finally the production and post- This course offers an in-depth examination of the popular horror film production processes. Assignments will emphasize visualization, through an analysis of its historical evolution, major theories, aesthetics shooting style, and production organization. Presentation of ideas in and conventions, and the impact of its role as a reflection of culture both the written word and visual media are integral to the production society. -

BILL THOMAS Director [email protected] Bill Is A

NOTE RE DATA PROTECTION: I CONSENT TO YOU KEEPING MY DETAILS ON FILE AND DISTRIBUTING FOR EMPLOYMENT PURPOSES. BILL THOMAS Director [email protected] Bill is a freelance director for TV. He’s directed documentary drama for nearly 100 episodes for various channels including BBC, National Geographic, Discovery, and Channel 5. In addition, he has directed a micro-budget feature film, shorts, online sketch comedy, 2nd Unit action, and miniature effects. He has also Edit Produced a number of documentaries, and directed audio drama plays. Bill has had a lot of experience directing units in the UK and abroad, including working with animals and children, pyrotechnics and action, various periods of history, modern day, blood/gore, VFX, and vehicles. He is passionate about creating high quality drama and has a reputation for getting the most out of limited time, resources, and budgets. BACKGROUND Originally from the North East of Scotland, Bill moved South and began working in film and TV art departments. Over the years he has worked as a Prop and Model Maker on many big budget movies. These include Star Wars, five of the Harry Potters, V for Vendetta, James Bond, and Christopher Nolan’s “The Dark Knight Rises”, as well as making various action props for The Bill, Family Affairs, and London’s Burning. He also worked as an Art Director on around 40 productions for various companies including: BBC Arts, Brook Lapping, Raw, Darlow Smithson, Wall to Wall, and Pioneer. LINKS SHOWREEL http://bthomas.net/showreels/ -

Unit Theory of Knowledge 1 UNIT: HISTORY IS a SHAPE

History is A Shape: History Unit Theory of Knowledge 1 UNIT: HISTORY IS A SHAPE Created by Amy Scott: Coral Reef High School Overall Unit Question: Does history move in a circle, an upwards progression, a downwards spiral, or a straight line? 1.Topic: History—in particular an examination of historical progress as it relates to time period and social setting. This unit will follow a discussion of “How to Think About Progress,” chapter 46 of Mortimer Adler’s The Great Ideas. The students will debate philosophically whether or not human societies experience real change, either physically or morally. Additionally moving from the world perspective to a specific American historical era, the student will project themselves back in time to “virtually” experience the economic and physical hazards of homesteading in the 1880’s. Through a series of pre-and-post film activities (based on the PBS film Frontier House) the student will consider whether or not “progress” necessarily leads to the overall betterment of men and their societies. Ultimately by looking at the merits and demerits of modern life compared to prairie life they will answer (at least for this time period) whether history moves upwards, circularly, downwards, or on a straight line. 2. Goals and Objectives: The student will learn how to think about progress as a concept of history. He will become familiar with the contrasting ideologies of Aristotle, Hegel, Kant, Marx, Spencer, Kant, and Toynbee. The student will also consider what conditions are indispensable to progress and try to clarify and isolate a specific definition of progress beyond the material realm. -

Thinking About Color and the 'Reality Effect' in the Cinema

revista Fronteiras – estudos midiáticos 16(3):215-227 setembro/dezembro 2014 © 2014 by Unisinos – doi: 10.4013/fem.2014.163.07 Thinking about color and the ‘Reality Effect’ in the cinema Considerando a cor e o “Efeito do Real” no cinema Maria Helena Braga e Vaz da Costa1 ABSTRACT A great number of different views regarding realism has been in evidence. Whether greater realism in the cinema is welcomed or whether it is criticized, there is no doubt that realism is always a matter of concern in discussions about cinema’s vocation. It is not easy to define realism, and even though the general opinion is that realism is a determining factor in the cinema, it was not always the only ideological need responsible for the introduction of new technologies into the cinema. This article will situate color within this perspective. Keywords: cinema, color, realism. RESUMO Um grande número de visões sobre o realismo cinematográfico tem estado em evidência. Independentemente da opinião se um maior realismo no cinema é bem-vindo ou deve ser criticado, parece não existir dúvida de que o realismo é sempre objeto de discussão no contexto da pretensa vocação do cinema. A temática do realismo é complexa, e mesmo que a opinião geral seja a de que o realismo é um fator determinante para o cinema, este não foi a única necessidade ideológica responsável pela introdução de novas tecnologias pelo aparato cinematográfico. Este artigo contextualiza a cor dentro dessa perspectiva. Palavras-chave: cinema, cor, realismo. Technological innovation can be explained, in the is no doubt that realism is always a matter of concern view of some authors, as the outcome of technological in discussions about cinema’s vocation. -

The Academy Journal

The A cademy Journal Lawrence Academ y/Fall 2012 IN THIS EDITION COMMENCEMENT 28 – 32 REUNION WEEKEND 35 – 39 ANNUAL REPORT 52 – 69 The best moments in my life in schools (and perhaps of life in First Word general) have contained a particular manner of energy. As I scan my past, certain images and sensations light up the sensors with by Dan Scheibe, Head of School an unusual intensity. I remember a day during my junior year in These truly “First Words” gravitate around the following high school when I was returning to my room after class on a particular and powerful forces: the beginning of the school year, bright but otherwise unspectacular day in the fall. The post-lunch the beginning of another chapter in Lawrence Academy’s rich glucose plunge was looming, but still, I acutely remember an history, and (obviously) the beginning of my tenure as head of unusual bounce in my stride as I approached my room on “The school. I draw both strength and conviction from the energies Plateau” (a grandiose name for the attic above the theater where associated with such beginnings. The auspicious nature of the they housed a small collection of altitude-tolerant boarders). moment makes it impossible to resist some enthusiastic The distinct physical sensations of lightness were accompanied introductory contemplations. by emotional sensations of delight not usually associated with Trustees of Lawrence Trustees with 25 or More Academy Years of Service Editors and Contributors Bruce M. MacNeil ’70, President 1793 –1827 Rev. Daniel Chaplin (34) Dave Casanave, Lucy C. Abisalih ’76, Vice President 1793 –1820 Rev. -

Literature and Film B5.140

ELiT Literaturehouse Europe Literature and Film B5.140 Ed. by Walter Grond and Beat Mazenauer Literature and Film Ed. by Walter Grond and Beat Mazenauer All contributions can be read on the website www.literaturhauseuropa.eu All rights reserved by the Authors/ELiT The Literaturehouse Europe is funded by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Union. Edition Rokfor Zürich/Berlin B5.140/18-12-2018 Konzeption: Rokfor Produktion: Gina Bucher Grafische Gestaltung: Rafael Koch Programmierung: Urs Hofer Gesamtherstellung: epubli, Berlin GET TO KNOW LITERATURE The Literaturhaus Europa was established in 2015 by institutions from six European countries and its mission was to spread the word about European contemporary literature. This set-up phase was achieved from 2015 to 2018 with support from the programme Creative Europe. A lively programme of events in Budapest, Hamburg, London, Ljubljana, Paris and in Wachau, Austria, was complemented with important publicity work under the title Observatory for European Contemporary Literature with weekly texts and blogs published about books, writers, trends or background analyses. The current fourth edition of «Trends in European Contemporary Literature» compiles a record of the European Literature Days 2018 with keynote texts by Katharina Hacker and Rüdiger Wischenbart on the topics of «Narrative in literature and film» and «The law of the series», plus a daily review by Ilinca Florian reflecting the content and atmosphere of the international festival. The main section of the fourth yearbook, as in previous years, com- prises texts published in the Observatory from January to December 2018 on the themes Europe, Trends in Contemporary Literature and Book Tips. -

Director/Producer

PIP GILMOUR - DIRECTOR/PRODUCER T +1 202-550-0220 PROFILE E: [email protected] W: www.pipgtv.com Pip is an experienced director, producer, writer and show runner with a reputation for delivering quality specials, series and national commercials. Her sense of story combined with her strong directing skills come together to create illuminating programs that entertain, inform and engage audiences. Pip thrives in a team environment and values her reputation for delivering projects on time and on budget. RECENT WORK AMC/Movistar LA FORTUNA 2nd unit producer for US production. MOD Pictures. CNN FILMS DIANA Field producer for US production. October Films. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC 911 Field Producer for US production. 72 Films. DISCOVERY CHANNEL KILLERS OF THE COSMOS Segment field director. Wall To Wall. HULU DOPESICK Director for promotionals. Riverside Entertainment. CAMPING WORLD TRAVEL DIFFERENT Writer/Director for new ad campaign. Just East Of West. BBC2 THE TRUMP SHOW Field producer for US production. 72 Films. SMITHSONIAN CHANNEL BEYOND STONEWALL Executive producer. Highland Pictures. CALL ME DANCER Director, documentary feature in-production. Shampaine Pictures. PRODUCTION CREDITS SMITHSONIAN CHANNEL • SERIOUSLY AMAZING OBJECTS (3 x 60 produced by Pip Gilmour Productions) Executive Producer, Show Runner & development producer • INCREDIBLE FLYING JETPACKS (1 x 60 produced by Pip Gilmour Productions) Executive Producer, Writer, Director and Development • INCREDIBLE FLYING CARS (2 x 60 produced by Pip Gilmour Productions) Executive Producer, Writer, -

Cultural Translations and East Asian Perspectives1 Sarah Cheang and Elizabeth Kramer

Fashion and East Asia: Cultural Translations and East Asian Perspectives1 Sarah Cheang and Elizabeth Kramer Introduction Fashion speaks to communities across borders, involving inter-lingual processes and translations across cultures, media, and sectors. This special issue explores East Asian fashion as a multifaceted process of cultural translation. Contributions to this special issue are drawn from the AHRC funded network project, ‘Fashion and Translation: Britain, Japan, China and Korea’ (2014-15)2, and the following articles investigate the role of clothing fashions as a powerful and pervasive cultural intermediary within East Asia as well as between East Asian and European cultures. Thinking about East Asia through transnational fashion allows us to analyze creative and cultural distinctiveness in relation to imitation, transformation and exchange, and to look for dialogues, rather than oppositions, between the global and the local. This approach is not only useful but also essential in a world that has been connected by textile trading networks for millennia, and yet feels increasingly characterized by the transnational and by globalized communication. As Sam Maher has asserted, ‘Few industries weave together the lives of people from all corners of the globe to quite the extent that the textile and garment industries do’ (2015-16: 11). The planet is connected through everyday clothing choices, and for millions the industry also provides their livelihood. In her discussion of transcultural art, Julie Codell emphasizes that borders ‘are permeable and liminal, not restrictive spaces’ and that we can see in the production, consumption and reception of transcultural art the coexistence of diverse cultures expressed in ambiguous, discontinuous or new ways (2012: 7). -

![Debt Shall Be [$2099572950]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1965/debt-shall-be-2099572950-1531965.webp)

Debt Shall Be [$2099572950]

SESSION OF 1988 Act 1988-23 111 No. 1988-23 AN ACT SB 515 Amending the act of December 8, 1982 (P.L.848, No.235), entitled “An act pro- viding for the adoption of capital projects related to the repair, rehabilitation or replacement of highway bridges to be financed from current revenue or by the incurring of debt and capital projects related to highway and safety improvement projects to be financed from current revenue of the Motor License Fund,” further providing for or adding projectsin Allegheny County, Beaver County, Bedford County, Berks County, Blair County, Bradford County, Bucks County, Butler County, Cambria County, Cameron County, Centre County, Chester County, Clearfield County, Crawford County, Cum- berland County, Dauphin County, Delaware County, Elk County, Erie County, Forest County, Franklin County, Fulton County, Greene County, Huntingdon County, Indiana County, Jefferson County, Lackawanna County, Lancaster County, Lawrence County, Lebanon County, Lehigh County, Luzerne County, Lycoming County, McKean County, Mercer County, Mifflin County, Monroe County, Montgomery County, North- ampton County, Northumberland County, Perry County, Philadelphia County, Pike County, Potter County, Schuylkill County, Snyder County, Somerset County, Susquehanna County, Tioga County, Venango County, Warren County, Washington County, Wayne County, Westmoreland County and Wyoming County; and making mathematicalcorrections. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania hereby enacts as follows: Section 1. Section 2 of the act of December 8, 1982 (P.L.848, No.235), known as the Highway-Railroad and Highway Bridge Capital Budget Act for 1982-1983, amended July 9, 1986 (P.L.597, No.100), is amended toread: Section 2. Total authorization for bridge projects. -

Bike Boom: the Unexpected Resurgence of Cycling, 217 DOI 10.5822/ 978-1-61091-817-6, © 2017 Carlton Reid

Acknowledgments Thanks to all at Island Press, including but not only Heather Boyer and Mike Fleming. For their patience, thanks are due to the loves of my life—my wife, Jude, and my children, Josh, Hanna, and Ellie Reid. Thanks also to my Kickstarter backers, listed overleaf. As much of this book is based on original research, it has involved wading through personal papers and dusty archives. Librarians in America and the UK proved to be exceptionally helpful. It was wonderful—albeit distracting— to work in such gob-stoppingly beautiful libraries such as the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, and the library at the Royal Automobile Club in London. I paid numerous (fruitful) visits to the National Cycling Archive at the Modern Records Centre at Warwick University, and while this doesn’t have the architectural splendor of the former libraries, it more than made up for it in the wonderful array of records deposited by the Cyclists’ Touring Club and other bodies. I also looked at Ministry of Transport papers held in The National Archives in Kew, London (which is the most technologically advanced archive I have ever visited, but the concrete building leaves a lot to be desired). Portions of chapters 1 and 6 were previously published in Roads Were Not Built for Cars (Carlton Reid, Island Press, 2015). However, I have expanded the content, including adding more period sources. Carlton Reid, Bike Boom: The Unexpected Resurgence of Cycling, 217 DOI 10.5822/ 978-1-61091-817-6, © 2017 Carlton Reid. Kickstarter Backers Philip Bowman Robin Holloway -

Web Search 1

Time Out!!! WEB SEARCH 1 Go to the following URL: http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest Your group’s focus is to search this Web site for the answers to the questions below. Once you have accessed this site, go to Events 1880-1890 to start your search. You may want to explore 1870-1880 as well. Your search will provide a historical context in which to better understand what our “real” life and fictional characters experienced during the 1800s. Good luck with your search! QUESTIONS: In 1882 what event would eventually affect the job market in the United States? Summarize this event. What happened in 1882 that made the West a little safer? Despite strong resistance, what event benefited white settlers? Whom did this event harm? What accomplishment changed the two-and-a-half year trip taken by Lewis and Clark to the Columbia River down to just a nine-day trip? Name some of the benefits and drawbacks of this accomplishment. Who was affected by the benefits and who was affected by the drawbacks? What environmental hazard was experienced? What caused the “near destruction of the Native American culture?” When did Montana join the Union? WEB SEARCH 1 ANSWER KEY http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest In 1882 what event would eventually affect the job market in the United States? Summarize this event. Chinese Exclusion Act What happened in 1882 that made the West a little safer? Jesse James was killed. Despite strong resistance, what event benefited white settlers? Land transfer Whom did this event harm? Lakota Indians What accomplishment changed the two-and-a-half year trip taken by Lewis and Clark to the Columbia River down to just a nine-day trip? Northern Pacific Railroad was completed. -

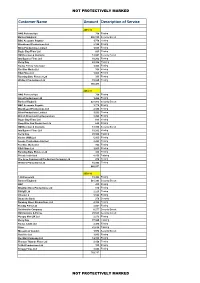

Customer Name Amount Description of Service

NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED Customer Name Amount Description of Service 2011-12 ANG Partnerships 708 Filming Bank of England 446,355 Security Escort BBC Accounts Payable 1,779 Filming Blackbeard Productions Ltd 2,180 Filming Blink Productions Limited 1,535 Filming Bugle Boy Films Ltd 661 Filming HM Revenue & Customs 12,041 Security Escort Intelligence Films Ltd 10,262 Filming Kerry Day 83,306 Training Kudos Film & Television 3,924 Filming Red Bee Media Ltd 354 Filming RSA Films Ltd 1,063 Filming Running Bare Pictures Ltd 333 Filming Winford Productions Ltd 15,985 Filming 580,485 2010-11 ANG Partnerships 708 Filming Anna Productions Ltd 1,266 Filming Bank of England 527,973 Security Escort BBC Accounts Payable 1,779 Filming Blackbeard Productions Ltd 2,180 Filming Blink Productions Limited 1,535 Filming British Broadcasting Corporation 2,495 Filming Bugle Boy Films Ltd 661 Filming Deep Blue Sea Production Ltd 649 Filming HM Revenue & Customs 17,150 Security Escort Intelligence Films Ltd 10,262 Filming Kerry Day 83,306 Training Kudos (WM) Ltd 5,105 Filming Locate Productions Limited 2,203 Filming Red Bee Media Ltd 354 Filming RSA Films Ltd 1,063 Filming Running Bare Pictures Ltd 333 Filming Private Individual 4,153 Training The Love Commercial Production Company Ltd 878 Filming Winford Productions Ltd 15,985 Filming 680,037 2009-10 1-800 Love Ltd 19,494 Filming Bank of England 581,343 Security Escort BBC 433 Filming Brighton Rock Productions Ltd 610 Filming BSKyB Ltd 2,223 Filming Channel 4 3,526 Filming Deutsche Bank 270 Security Dombey Street