Literature and Film B5.140

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michał Krzykawski, Zuzanna Szatanik Gender Studies in French

Michał Krzykawski, Zuzanna Szatanik Gender Studies in French Romanica Silesiana 8/1, 22-30 2013 Mi c h a ł Kr z y K a w s K i , zu z a n n a sz a t a n i K University of Silesia Gender Studies in French They are seen as black therefore they are black; they are seen as women, therefore, they are women. But before being seen that way, they first had to be made that way. Monique WITTIG 12 Within Anglo-American academia, gender studies and feminist theory are recognized to be creditable, fully institutionalized fields of knowledge. In France, however, their standing appears to be considerably lower. One could risk the statement that while in Anglo-American academic world, gender studies have developed into a valid and independent critical theory, the French academe is wary of any discourse that subverts traditional universalism and humanism. A notable example of this suspiciousness is the fact that Judith Butler’s Gen- der Trouble: Feminism and a Subversion of Identity, whose publication in 1990 marked a breakthrough moment for the development of both gender studies and feminist theory, was not translated into French until 2005. On the one hand, therefore, it seems that in this respect not much has changed in French literary studies since 1981, when Jean d’Ormesson welcomed the first woman, Marguerite Yourcenar, to the French Academy with a speech which stressed that the Academy “was not changing with the times, redefining itself in the light of the forces of feminism. Yourcenar just happened to be a woman” (BEASLEY 2, my italics). -

Pour Une Littérature-Monde En Français”: Notes for a Rereading of the Manifesto

#12 “POUR UNE LITTÉRATURE-MONDE EN FRANÇAIS”: NOTES FOR A REREADING OF THE MANIFESTO Soledad Pereyra CONICET – Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas Instituto de Investigaciones en Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales (UNLP – CONICET). Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad Nacional de La Plata – Argentina María Julia Zaparart Instituto de Investigaciones en Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales (UNLP – CONICET). Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad Nacional de La Plata – Argentina Illustration || Paula Cuadros Translation || Joel Gutiérrez and Eloise Mc Inerney 214 Article || Received on: 31/07/2014 | International Advisory Board’s suitability: 12/11/2014 | Published: 01/2015 License || Creative Commons Attribution Published -Non commercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. 452ºF Abstract || The manifesto “Pour une littérature-monde en français” (2007) questioned for the first time in a newspaper of record the classification of the corpus of contemporary French literature in terms of categories of colonial conventions: French literature and Francopohone literature. A re-reading of the manifesto allows us to interrogate the supplementary logic (in Derrida’s term) between Francophone literatures and French literature through analyzing the controversies around the manifesto and some French literary awards of the last decade. This reconstruction allows us to examine the possibilities and limits of the notions of Francophonie and world-literature in French. Finally, this overall critical approach is demonstrated in the analysis of Atiq Rahimi’s novel Syngué sabour. Pierre de patience. Keywords || French Literature | Francophonie | Transnational Literatures | Atiq Rahimi 215 The manifesto “Pour une littérature-monde en français” appeared in the respected French newspaper Le monde des livres in March NOTES 1 2007. -

2012-13 Humanities Undergraduate Stage 2 & 3 Module Handbook

2012-13 Humanities Undergraduate Stage 2 & 3 Module Handbook 04 School of European Culture and Languages CL310 Greek for Beginners Version Campus Term(s) Level Credit (ECTS) Assessment Convenor 1 Canterbury Autumn and C 30 (15) 80% Exam, 20% Coursework Alwis Dr A Spring Contact Hours 1 hour seminar and 2 hour seminar per week Method of Assessment 20% Coursework (two assessment tests of equal weighting); 80% Exam Synopsis The aim of the module is to provide students with a firm foundation in the Classical Greek language. The text book used combines grammar and syntax with passages about a farmer and his family living in fifth-century Attica. As the story progresses, we move onto the Peloponnesian war and thus adapted texts of Thucydides. Reading is therefore ensured from the very first lesson. Extracts from the Bible will also be used. The module will follow the structured approach of Athenaze I (OUP). Preliminary Reading $%%27 0$16),(/' $3ULPHURI*UHHN*UDPPDU$FFLGHQFHDQG6\QWD[ 'XFNZRUWK 0%$/0( */$:$// $WKHQD]H, 283UHYLVHGHG CL311 Latin for Beginners Version Campus Term(s) Level Credit (ECTS) Assessment Convenor 1 Canterbury Autumn and C 30 (15) 80% Exam, 20% Coursework Keaveney Dr A Spring Contact Hours 44 contact hours (22 lectures, 22 classes) Method of Assessment Synopsis This course introduces Latin to complete, or near, beginners, aiming to cover the basic aspects of grammar required for understanding, reading and translating this ancient language. Using a textbook, in which each chapter focuses on different topics of grammar, the students apply what they have learnt through the translation of sentences adapted from ancient authors. -

Experiencing Literature 72

Udasmoro / Experiencing Literature 72 EXPERIENCING LITERATURE Discourses of Islam through Michel Houellebecq’s Soumission Wening Udasmoro Universitas Gadjah Mada [email protected] Abstract This article departs from the conventional assumption that works of literature are only texts to be read. Instead, it argues that readers bring these works to life by contextualizing them within themselves and draw from their own life experiences to understand these literary texts’ deeper meanings and themes. Using Soumission (Surrender), a controversial French novel that utilizes stereotypes in its exploration of Islam in France, this research focuses on the consumption of literary texts by French readers who are living or have lived in a country with a Muslim majority, specifically Indonesia. It examines how the novel’s stereotypes of Muslims and Islam are understood by a sample of French readers with experience living in Indonesia. The research problematizes whether a textual and contextual gap exists in their reading of the novel, and how they justify this gap in their social practices. In any reading of a text, the literal meaning (surface meaning) is taken as it is or the hidden meaning (deep meaning), but in a text that is covert in meaning, the reader may either venture into probing the underlying true meaning or accept the literal meaning of the text. However, this remains a point of contention and this research explores this issue using critical discourse analysis in Soumission’s text, in which the author presents the narrator’s views about Islam. The question that underpins this analysis is whether a reader’s life experiences and the context influence his or her view about Islam in interpreting Soumission’s text. -

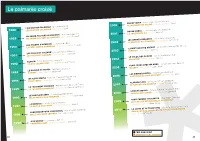

Le Palmarès Croisé

Le palmarès croisé 1988 L’EXPOSITION COLONIALE - Erik Orsenna (Seuil) INGRID CAVEN - Jean-Jacques Schuhl (Gallimard) L’EXPOSITION COLONIALE - Erik Orsenna (Seuil) 2000 ALLAH N’EST PAS OBLIGÉ - Ahmadou Kourouma (Seuil) UN GRAND PAS VERS LE BON DIEU - Jean Vautrin (Grasset) ROUGE BRÉSIL - Jean-Christophe Rufin (Gallimard) 1989 UN GRAND PAS VERS LE BON DIEU - Jean Vautrin (Grasset) 2001 LA JOUEUSE DE GO - Shan Sa (Grasset) LES CHAMPS D’HONNEUR - Jean Rouaud (Minuit) LES OMBRES ERRANTES - Pascal Quignard (Grasset) 1990 LE PETIT PRINCE CANNIBALE - Françoise Lefèvre (Actes Sud) 2002 LA MORT DU ROI TSONGOR - Laurent Gaudé (Actes Sud) 1991 LES FILLES DU CALVAIRE - Pierre Combescot (Grasset) LA MAÎTRESSE DE BRECHT - Jacques-Pierre Amette (Albin Michel) LES FILLES DU CALVAIRE - Pierre Combescot (Grasset) 2003 FARRAGO - Yann Apperry (Grasset) TEXACO - Patrick Chamoiseau (Gallimard) 1992 LE SOLEIL DES SCORTA - Laurent Gaudé (Actes Sud) L’ÎLE DU LÉZARD VERT - Edouardo Manet (Flammarion) 2004 UN SECRET - Philippe Grimbert (Grasset) 1993 LE ROCHER DE TANIOS - Amin Maalouf (Grasset) TROIS JOURS CHEZ MA MÈRE - François Weyergans (Grasset) CANINES - Anne Wiazemsky (Gallimard) 2005 MAGNUS - Sylvie Germain (Albin Michel) 1994 UN ALLER SIMPLE - Didier Van Cauwelaert (Albin Michel) LES BIENVEILLANTES - Jonathan Littell (Gallimard) BELLE-MÈRE - Claude Pujade-Renaud (Actes Sud) 2006 CONTOURS DU JOUR QUI VIENT - Léonora Miano (Plon) LE TESTAMENT FRANÇAIS - Andreï Makine (Mercure de France) 1995 ALABAMA SONG - Gilles Leroy (Mercure de France) LE TESTAMENT FRANÇAIS -

BILL THOMAS Director [email protected] Bill Is A

NOTE RE DATA PROTECTION: I CONSENT TO YOU KEEPING MY DETAILS ON FILE AND DISTRIBUTING FOR EMPLOYMENT PURPOSES. BILL THOMAS Director [email protected] Bill is a freelance director for TV. He’s directed documentary drama for nearly 100 episodes for various channels including BBC, National Geographic, Discovery, and Channel 5. In addition, he has directed a micro-budget feature film, shorts, online sketch comedy, 2nd Unit action, and miniature effects. He has also Edit Produced a number of documentaries, and directed audio drama plays. Bill has had a lot of experience directing units in the UK and abroad, including working with animals and children, pyrotechnics and action, various periods of history, modern day, blood/gore, VFX, and vehicles. He is passionate about creating high quality drama and has a reputation for getting the most out of limited time, resources, and budgets. BACKGROUND Originally from the North East of Scotland, Bill moved South and began working in film and TV art departments. Over the years he has worked as a Prop and Model Maker on many big budget movies. These include Star Wars, five of the Harry Potters, V for Vendetta, James Bond, and Christopher Nolan’s “The Dark Knight Rises”, as well as making various action props for The Bill, Family Affairs, and London’s Burning. He also worked as an Art Director on around 40 productions for various companies including: BBC Arts, Brook Lapping, Raw, Darlow Smithson, Wall to Wall, and Pioneer. LINKS SHOWREEL http://bthomas.net/showreels/ -

Victims of History and Culture: Women in the Novels of Khaled Hosseini and Siba Shakib

VICTIMS OF HISTORY AND CULTURE: WOMEN IN THE NOVELS OF KHALED HOSSEINI AND SIBA SHAKIB ABSTRACT THESIS V : SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF IN t ENGLISH j^ BY JAMSHEED AHMAD T7880 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Dr. Aysha Munira Rasheed DEPftRTMKNT OF ENGblSH ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY AUGARH -202002 (INDIA) 2012 T7880 Abstract The thesis entitled "Victimsof History and Culture: Women in the Novels of Khaled Hosseini and Siba Shakib" has been chapterised into four chapters. It attempts to discuss the victimization of women characters in the hands of history and culture. Women and History Though the novels concerned are not historical in the strict sense of the word, the title of the thesis demands a parallel study of literary (the novels) and non-literary (the history of the country) texts. Both the novelists have drawn in abundance from the historical happenings of Afghanistan. The unstable political history of Afghanistan which had been marked by power struggles, armed revolts and mass uprisings had a direct bearing on the social fabric of this multi-ethnic country which is well mirrored in the novels. History of Afghanistan stands a testimony to the fact that the issues related to women have always been one of the various reasons for unstable polity. A cursory examination of history reveals that at various junctures in the history, the issues related to women have been among the reasons behind the fall of various regimes. Afghanistan is a country with deep patriarchal roots and a tribal-based family structure. In Afghanistan, family is at the heart of the society. -

Diversity Report 2010 1 Diversity Report 2010 Literary Translation in Current European Book Markets

Diversity Report 2010 1 Diversity Report 2010 Literary Translation in Current European Book Markets. An analysis of authors, languages, and flows. Written by Miha Kovač and Rüdiger Wischenbart, with Jennifer Jursitzky and Sabine Kaldonek, and additional research by Julia Coufal. www.wischenbart.com/DiversityReport2010 Contact: [email protected] 2 Executive Summary The Diversity Report 2010, building on previous research presented in the respective reports of 2008 and 2009, surveys and analyzes 187 mostly European authors of contemporary fiction concerning translations of their works in 14 European languages and book markets. The goal of this study is to develop a more structured, data-based understanding of the patterns and driving forces of the translation markets across Europe. The key questions include the following: What characterizes the writers who succeed particularly well at being picked up by scouts, agents, and publishers for translation? Are patterns recognizable in the writers’ working biographies or their cultural background, the language in which a work is initially written, or the target languages most open for new voices? What forces shape a well-established literary career internationally? What channels and platforms are most helpful, or critical, for starting a path in translation? How do translations spread? The Diversity Report 2010 argues that translated books reflect a broad diversity of authors and styles, languages and career paths. We have confirmed, as a trend with great momentum, that the few authors and books at the very top, in terms of sales and recognition, expand their share of the overall reading markets with remarkable vigor. Not only are the real global stars to be counted on not very many fingers. -

Director/Producer

PIP GILMOUR - DIRECTOR/PRODUCER T +1 202-550-0220 PROFILE E: [email protected] W: www.pipgtv.com Pip is an experienced director, producer, writer and show runner with a reputation for delivering quality specials, series and national commercials. Her sense of story combined with her strong directing skills come together to create illuminating programs that entertain, inform and engage audiences. Pip thrives in a team environment and values her reputation for delivering projects on time and on budget. RECENT WORK AMC/Movistar LA FORTUNA 2nd unit producer for US production. MOD Pictures. CNN FILMS DIANA Field producer for US production. October Films. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC 911 Field Producer for US production. 72 Films. DISCOVERY CHANNEL KILLERS OF THE COSMOS Segment field director. Wall To Wall. HULU DOPESICK Director for promotionals. Riverside Entertainment. CAMPING WORLD TRAVEL DIFFERENT Writer/Director for new ad campaign. Just East Of West. BBC2 THE TRUMP SHOW Field producer for US production. 72 Films. SMITHSONIAN CHANNEL BEYOND STONEWALL Executive producer. Highland Pictures. CALL ME DANCER Director, documentary feature in-production. Shampaine Pictures. PRODUCTION CREDITS SMITHSONIAN CHANNEL • SERIOUSLY AMAZING OBJECTS (3 x 60 produced by Pip Gilmour Productions) Executive Producer, Show Runner & development producer • INCREDIBLE FLYING JETPACKS (1 x 60 produced by Pip Gilmour Productions) Executive Producer, Writer, Director and Development • INCREDIBLE FLYING CARS (2 x 60 produced by Pip Gilmour Productions) Executive Producer, Writer, -

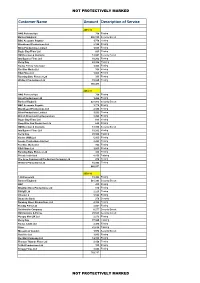

Customer Name Amount Description of Service

NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED Customer Name Amount Description of Service 2011-12 ANG Partnerships 708 Filming Bank of England 446,355 Security Escort BBC Accounts Payable 1,779 Filming Blackbeard Productions Ltd 2,180 Filming Blink Productions Limited 1,535 Filming Bugle Boy Films Ltd 661 Filming HM Revenue & Customs 12,041 Security Escort Intelligence Films Ltd 10,262 Filming Kerry Day 83,306 Training Kudos Film & Television 3,924 Filming Red Bee Media Ltd 354 Filming RSA Films Ltd 1,063 Filming Running Bare Pictures Ltd 333 Filming Winford Productions Ltd 15,985 Filming 580,485 2010-11 ANG Partnerships 708 Filming Anna Productions Ltd 1,266 Filming Bank of England 527,973 Security Escort BBC Accounts Payable 1,779 Filming Blackbeard Productions Ltd 2,180 Filming Blink Productions Limited 1,535 Filming British Broadcasting Corporation 2,495 Filming Bugle Boy Films Ltd 661 Filming Deep Blue Sea Production Ltd 649 Filming HM Revenue & Customs 17,150 Security Escort Intelligence Films Ltd 10,262 Filming Kerry Day 83,306 Training Kudos (WM) Ltd 5,105 Filming Locate Productions Limited 2,203 Filming Red Bee Media Ltd 354 Filming RSA Films Ltd 1,063 Filming Running Bare Pictures Ltd 333 Filming Private Individual 4,153 Training The Love Commercial Production Company Ltd 878 Filming Winford Productions Ltd 15,985 Filming 680,037 2009-10 1-800 Love Ltd 19,494 Filming Bank of England 581,343 Security Escort BBC 433 Filming Brighton Rock Productions Ltd 610 Filming BSKyB Ltd 2,223 Filming Channel 4 3,526 Filming Deutsche Bank 270 Security Dombey Street -

Filming in Lincoln's

Film Productions in Lincoln’s Inn Because of its varied architecture, beautiful gardens, spacious squares, historic halls and panelled rooms, Lincoln’s Inn has long been used by film production companies as a location, and by television companies for interviews as well as drama productions with either a legal theme or a period setting. Among productions which have used the Inn are: 2017 The Children’s Act (FilmNation Entertainment) 2016 Limehouse Golem (New Sparta Films) Richard III (Documentary, BFI) 2015 Wonder Woman (Warner Brothers) Suffragette (Gillerd Production Services Limited) Grantchester Limited (ITV) Downton Abbey (BBC) Spotless (Spotless Productions Ltd) Partners in Crime (BBC) SS-GB (BBC) Who Do You Think You Are? (Wall to Wall Media) Defenders of the Sky (History Channel) 2014 Suffragette (Gillerd Production Services Limited) Grantchester (ITV) The Suspicions of Mr Whicher (ITV) Welsh History Series – Huw Edwards (BBC) Secrets from the Clink (ITV) PAN (Dombey Street Productions) The Theory of Everything (Cosmos Ltd) Mr Holmes (Slight Trick Productions Ltd) The Man who knew Infinity (Pinewood Studios) Spotless (Spotless Productions Ltd) Partners in Crime (BBC) Silent Witness (BBC) 2013 Agatha Christies’ Poirot (ITV Studios Limited) Dracula (Carnival Productions Ltd) The Muppets…Again (More Muppets Productions Limited) Angelica (Angelica Film Productions Inc) Downtown Abbey Series Four (Carnival Productions Ltd) Fleming (Ecosse Films) Shakespeare’s London Theatres (Illuminations TV) 2012 Shakespeare’s London Theatres (Illuminations -

From Media Hype to Twitter Storm from Media Hype to Twitter Storm

Peter VastermanPeter (ed.) Peter Vasterman (ed.) From Media Hype to Twitter Storm News Explosions and From Media Hype to Twitter Storm Twitter to Hype Media From Their Impact on Issues, Crises and Public Opinion From Media Hype to Twitter Storm From Media Hype to Twitter Storm News Explosions and Their Impact on Issues, Crises, and Public Opinion Edited by Peter Vasterman Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Alain Delorme, MURMURATIONS Ephemeral Plastic Sculptures #2. www.alaindelorme.com Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 217 8 e-isbn 978 90 4853 210 0 doi 10.5117/9789462982178 nur 811 © P. Vasterman / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2018 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. It is not difficult to see the similarities between massive starling flocks, flying as one and creating new shapes – murmurations – and the way media operate during explosive news waves, the main topic in this book. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 11 Preface 13 Hans Mathias Kepplinger Introduction 17 Peter Vasterman I.