Maria Rubins “Neither East Nor West: Polyphony and Deterritorialisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michał Krzykawski, Zuzanna Szatanik Gender Studies in French

Michał Krzykawski, Zuzanna Szatanik Gender Studies in French Romanica Silesiana 8/1, 22-30 2013 Mi c h a ł Kr z y K a w s K i , zu z a n n a sz a t a n i K University of Silesia Gender Studies in French They are seen as black therefore they are black; they are seen as women, therefore, they are women. But before being seen that way, they first had to be made that way. Monique WITTIG 12 Within Anglo-American academia, gender studies and feminist theory are recognized to be creditable, fully institutionalized fields of knowledge. In France, however, their standing appears to be considerably lower. One could risk the statement that while in Anglo-American academic world, gender studies have developed into a valid and independent critical theory, the French academe is wary of any discourse that subverts traditional universalism and humanism. A notable example of this suspiciousness is the fact that Judith Butler’s Gen- der Trouble: Feminism and a Subversion of Identity, whose publication in 1990 marked a breakthrough moment for the development of both gender studies and feminist theory, was not translated into French until 2005. On the one hand, therefore, it seems that in this respect not much has changed in French literary studies since 1981, when Jean d’Ormesson welcomed the first woman, Marguerite Yourcenar, to the French Academy with a speech which stressed that the Academy “was not changing with the times, redefining itself in the light of the forces of feminism. Yourcenar just happened to be a woman” (BEASLEY 2, my italics). -

Nimble Tongues: Studies in Literary Translingualism

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Book Previews Purdue University Press 2-2020 Nimble Tongues: Studies in Literary Translingualism Steven G. Kellman Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_previews Part of the Language Interpretation and Translation Commons This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. NIMBLE TongueS Comparative Cultural Studies Ari Ofengenden, Series Editor The series examines how cultural practices, especially contemporary creative media, both shape and themselves are shaped by current global developments such as the digitization of culture, virtual reality, global interconnectedness, increased people flows, transhumanism, environ- mental degradation, and new forms of subjectivities. We aim to publish manuscripts that cross disciplines and national borders in order to pro- vide deep insights into these issues. Other titles in this series Imagining Afghanistan: Global Fiction and Film of the 9/11 Wars Alla Ivanchikova The Quest for Redemption: Central European Jewish Thought in Joseph Roth’s Works Rares G. Piloiu Perspectives on Science and Culture Kris Rutten, Stefaan Blancke, and Ronald Soetaert Faust Adaptations from Marlowe to Aboudoma and Markland Lorna Fitzsimmons (Ed.) Subjectivity in ʿAṭṭār, Persian Sufism, and European Mysticism Claudia Yaghoobi Reconsidering the Emergence of the Gay Novel in English and German James P. Wilper Cultural Exchanges between Brazil and France Regina R. Félix and Scott D. Juall (Eds.) Transcultural Writers and Novels in the Age of Global Mobility Arianna Dagnino NIMBLE TongueS Studies in Literary Translingualism Steven G. Kellman Purdue University Press • West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright 2020 by Purdue University. -

Pour Une Littérature-Monde En Français”: Notes for a Rereading of the Manifesto

#12 “POUR UNE LITTÉRATURE-MONDE EN FRANÇAIS”: NOTES FOR A REREADING OF THE MANIFESTO Soledad Pereyra CONICET – Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas Instituto de Investigaciones en Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales (UNLP – CONICET). Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad Nacional de La Plata – Argentina María Julia Zaparart Instituto de Investigaciones en Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales (UNLP – CONICET). Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad Nacional de La Plata – Argentina Illustration || Paula Cuadros Translation || Joel Gutiérrez and Eloise Mc Inerney 214 Article || Received on: 31/07/2014 | International Advisory Board’s suitability: 12/11/2014 | Published: 01/2015 License || Creative Commons Attribution Published -Non commercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. 452ºF Abstract || The manifesto “Pour une littérature-monde en français” (2007) questioned for the first time in a newspaper of record the classification of the corpus of contemporary French literature in terms of categories of colonial conventions: French literature and Francopohone literature. A re-reading of the manifesto allows us to interrogate the supplementary logic (in Derrida’s term) between Francophone literatures and French literature through analyzing the controversies around the manifesto and some French literary awards of the last decade. This reconstruction allows us to examine the possibilities and limits of the notions of Francophonie and world-literature in French. Finally, this overall critical approach is demonstrated in the analysis of Atiq Rahimi’s novel Syngué sabour. Pierre de patience. Keywords || French Literature | Francophonie | Transnational Literatures | Atiq Rahimi 215 The manifesto “Pour une littérature-monde en français” appeared in the respected French newspaper Le monde des livres in March NOTES 1 2007. -

2012-13 Humanities Undergraduate Stage 2 & 3 Module Handbook

2012-13 Humanities Undergraduate Stage 2 & 3 Module Handbook 04 School of European Culture and Languages CL310 Greek for Beginners Version Campus Term(s) Level Credit (ECTS) Assessment Convenor 1 Canterbury Autumn and C 30 (15) 80% Exam, 20% Coursework Alwis Dr A Spring Contact Hours 1 hour seminar and 2 hour seminar per week Method of Assessment 20% Coursework (two assessment tests of equal weighting); 80% Exam Synopsis The aim of the module is to provide students with a firm foundation in the Classical Greek language. The text book used combines grammar and syntax with passages about a farmer and his family living in fifth-century Attica. As the story progresses, we move onto the Peloponnesian war and thus adapted texts of Thucydides. Reading is therefore ensured from the very first lesson. Extracts from the Bible will also be used. The module will follow the structured approach of Athenaze I (OUP). Preliminary Reading $%%27 0$16),(/' $3ULPHURI*UHHN*UDPPDU$FFLGHQFHDQG6\QWD[ 'XFNZRUWK 0%$/0( */$:$// $WKHQD]H, 283UHYLVHGHG CL311 Latin for Beginners Version Campus Term(s) Level Credit (ECTS) Assessment Convenor 1 Canterbury Autumn and C 30 (15) 80% Exam, 20% Coursework Keaveney Dr A Spring Contact Hours 44 contact hours (22 lectures, 22 classes) Method of Assessment Synopsis This course introduces Latin to complete, or near, beginners, aiming to cover the basic aspects of grammar required for understanding, reading and translating this ancient language. Using a textbook, in which each chapter focuses on different topics of grammar, the students apply what they have learnt through the translation of sentences adapted from ancient authors. -

Experiencing Literature 72

Udasmoro / Experiencing Literature 72 EXPERIENCING LITERATURE Discourses of Islam through Michel Houellebecq’s Soumission Wening Udasmoro Universitas Gadjah Mada [email protected] Abstract This article departs from the conventional assumption that works of literature are only texts to be read. Instead, it argues that readers bring these works to life by contextualizing them within themselves and draw from their own life experiences to understand these literary texts’ deeper meanings and themes. Using Soumission (Surrender), a controversial French novel that utilizes stereotypes in its exploration of Islam in France, this research focuses on the consumption of literary texts by French readers who are living or have lived in a country with a Muslim majority, specifically Indonesia. It examines how the novel’s stereotypes of Muslims and Islam are understood by a sample of French readers with experience living in Indonesia. The research problematizes whether a textual and contextual gap exists in their reading of the novel, and how they justify this gap in their social practices. In any reading of a text, the literal meaning (surface meaning) is taken as it is or the hidden meaning (deep meaning), but in a text that is covert in meaning, the reader may either venture into probing the underlying true meaning or accept the literal meaning of the text. However, this remains a point of contention and this research explores this issue using critical discourse analysis in Soumission’s text, in which the author presents the narrator’s views about Islam. The question that underpins this analysis is whether a reader’s life experiences and the context influence his or her view about Islam in interpreting Soumission’s text. -

Jean-Christophe RUFIN, Président D'honneur De L'édition 2017 De LIVR

Jean-Christophe RUFIN, Président d’honneur de l’édition 2017 de LIVR’ À VANNES LEVR E GWENED La 10 e édition du salon littéraire LIVR’À VANNES aura lieu les 9, 10 et 11 juin 2017 dans les jardins des Remparts de Vannes, en présence de 200 auteurs de littérature générale, bretonne, BD et jeunesse. Pour fêter les 10 ans de l’un des plus grands événements littéraires bretons gratuits attirant chaque année 30 000 visiteurs, la Ville de Vannes est fière d’annoncer que Jean-Christophe RUFIN sera le Président d’honneur de la prochaine édition. Présidé par Patrick Mahé avec à la direction artistique Sylvie Rostain, le salon LIVR’À VANNES est organisé par la Ville de Vannes, en partenariat avec cinq libraires généralistes et spécialisés de Vannes. Les 10 ans de l’événement marquent aussi le changement de nom du Salon du Livre en Bretagne, qui devient LIVR’À VANNES / LEVR E GWENED . PRÉSIDENT D’HONNEUR DE LIVR’À VANNES 2017 : Jean-Christophe RUFIN Médecin de formation, engagé très tôt dans le mouvement humanitaire, mais aussi voyageur et diplomate, Jean-Christophe Rufin est écrivain multiple. Membre de l’Académie française depuis 2008, on lui doit pas moins de trois essais politiques et quatorze œuvres littéraires. Son quinzième roman, Le tour du monde du roi Zibeline sortira en avril prochain (Éditions Gallimard, Roman, Blanche, Avril 2017). © F. Mantovani. Biographie : Né en 1952 à Bourges dans le Cher, il étudie au lycée Claude Bernard à Paris, reçoit le diplôme de l’Institut d’études politiques de Paris et par la suite devient médecin, interne et chef de clinique à la faculté de médecine de Paris. -

Encounter: Essays by Milan Kundera

TIM JONES is a PhD candidate at the University of East Anglia in Norwich. His thesis explores Milan Kundera's three, critically-neglected French novels, Slowness, Identity, and Ignorance. His paper on Slowness can be found at the Review of European Studies website. Book Review Encounter: Essays by Milan Kundera Trans. by Linda Asher, London: Faber and Faber, 2010, 192 pp., £12.99, ISBN 978-0-571-25089-9 / Tim Jones ALMOST EXACTLY HALFWAY THROUGH his latest collection of essays, Milan Kundera provides, in a manner with which readers of both his fiction and non- fiction will be familiar, a working definition of the noun that he has chosen for his title. An encounter, he informs us, is ‘not a social relation, not a friendship, not even an alliance’, but ‘a spark; a lightning flash; random chance’ (pp. 83– 84). This explanation grants some cohesion between the thematic concerns and peformative elements of a book in danger of appearing frustratingly eclectic, which blends reworked versions of material published elsewhere—in some cases, as with Kundera’s musings on musician Iannis Xenakis, decades ago— with entirely new compositions, together introducing a series of fascinating subjects but mostly refusing to dwell on any single one for more than a few short paragraphs. The second of Encounter’s nine parts, for example, discusses several European novels that Kundera finds particularly interesting, but in affording each only two or three pages his explorations often sound much like the truncated soundbites that novels of his own, such as Immortality and Slowness, work hard to denounce. -

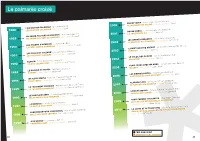

Le Palmarès Croisé

Le palmarès croisé 1988 L’EXPOSITION COLONIALE - Erik Orsenna (Seuil) INGRID CAVEN - Jean-Jacques Schuhl (Gallimard) L’EXPOSITION COLONIALE - Erik Orsenna (Seuil) 2000 ALLAH N’EST PAS OBLIGÉ - Ahmadou Kourouma (Seuil) UN GRAND PAS VERS LE BON DIEU - Jean Vautrin (Grasset) ROUGE BRÉSIL - Jean-Christophe Rufin (Gallimard) 1989 UN GRAND PAS VERS LE BON DIEU - Jean Vautrin (Grasset) 2001 LA JOUEUSE DE GO - Shan Sa (Grasset) LES CHAMPS D’HONNEUR - Jean Rouaud (Minuit) LES OMBRES ERRANTES - Pascal Quignard (Grasset) 1990 LE PETIT PRINCE CANNIBALE - Françoise Lefèvre (Actes Sud) 2002 LA MORT DU ROI TSONGOR - Laurent Gaudé (Actes Sud) 1991 LES FILLES DU CALVAIRE - Pierre Combescot (Grasset) LA MAÎTRESSE DE BRECHT - Jacques-Pierre Amette (Albin Michel) LES FILLES DU CALVAIRE - Pierre Combescot (Grasset) 2003 FARRAGO - Yann Apperry (Grasset) TEXACO - Patrick Chamoiseau (Gallimard) 1992 LE SOLEIL DES SCORTA - Laurent Gaudé (Actes Sud) L’ÎLE DU LÉZARD VERT - Edouardo Manet (Flammarion) 2004 UN SECRET - Philippe Grimbert (Grasset) 1993 LE ROCHER DE TANIOS - Amin Maalouf (Grasset) TROIS JOURS CHEZ MA MÈRE - François Weyergans (Grasset) CANINES - Anne Wiazemsky (Gallimard) 2005 MAGNUS - Sylvie Germain (Albin Michel) 1994 UN ALLER SIMPLE - Didier Van Cauwelaert (Albin Michel) LES BIENVEILLANTES - Jonathan Littell (Gallimard) BELLE-MÈRE - Claude Pujade-Renaud (Actes Sud) 2006 CONTOURS DU JOUR QUI VIENT - Léonora Miano (Plon) LE TESTAMENT FRANÇAIS - Andreï Makine (Mercure de France) 1995 ALABAMA SONG - Gilles Leroy (Mercure de France) LE TESTAMENT FRANÇAIS -

Victims of History and Culture: Women in the Novels of Khaled Hosseini and Siba Shakib

VICTIMS OF HISTORY AND CULTURE: WOMEN IN THE NOVELS OF KHALED HOSSEINI AND SIBA SHAKIB ABSTRACT THESIS V : SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF IN t ENGLISH j^ BY JAMSHEED AHMAD T7880 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Dr. Aysha Munira Rasheed DEPftRTMKNT OF ENGblSH ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY AUGARH -202002 (INDIA) 2012 T7880 Abstract The thesis entitled "Victimsof History and Culture: Women in the Novels of Khaled Hosseini and Siba Shakib" has been chapterised into four chapters. It attempts to discuss the victimization of women characters in the hands of history and culture. Women and History Though the novels concerned are not historical in the strict sense of the word, the title of the thesis demands a parallel study of literary (the novels) and non-literary (the history of the country) texts. Both the novelists have drawn in abundance from the historical happenings of Afghanistan. The unstable political history of Afghanistan which had been marked by power struggles, armed revolts and mass uprisings had a direct bearing on the social fabric of this multi-ethnic country which is well mirrored in the novels. History of Afghanistan stands a testimony to the fact that the issues related to women have always been one of the various reasons for unstable polity. A cursory examination of history reveals that at various junctures in the history, the issues related to women have been among the reasons behind the fall of various regimes. Afghanistan is a country with deep patriarchal roots and a tribal-based family structure. In Afghanistan, family is at the heart of the society. -

Diversity Report 2010 1 Diversity Report 2010 Literary Translation in Current European Book Markets

Diversity Report 2010 1 Diversity Report 2010 Literary Translation in Current European Book Markets. An analysis of authors, languages, and flows. Written by Miha Kovač and Rüdiger Wischenbart, with Jennifer Jursitzky and Sabine Kaldonek, and additional research by Julia Coufal. www.wischenbart.com/DiversityReport2010 Contact: [email protected] 2 Executive Summary The Diversity Report 2010, building on previous research presented in the respective reports of 2008 and 2009, surveys and analyzes 187 mostly European authors of contemporary fiction concerning translations of their works in 14 European languages and book markets. The goal of this study is to develop a more structured, data-based understanding of the patterns and driving forces of the translation markets across Europe. The key questions include the following: What characterizes the writers who succeed particularly well at being picked up by scouts, agents, and publishers for translation? Are patterns recognizable in the writers’ working biographies or their cultural background, the language in which a work is initially written, or the target languages most open for new voices? What forces shape a well-established literary career internationally? What channels and platforms are most helpful, or critical, for starting a path in translation? How do translations spread? The Diversity Report 2010 argues that translated books reflect a broad diversity of authors and styles, languages and career paths. We have confirmed, as a trend with great momentum, that the few authors and books at the very top, in terms of sales and recognition, expand their share of the overall reading markets with remarkable vigor. Not only are the real global stars to be counted on not very many fingers. -

The Curtain: an Essay in Seven Parts

The Curtain: An Essay in Seven Parts HarperCollins, 2007 - 176 pages - 0060841958, 9780060841959 - 2007 - The Curtain: An Essay in Seven Parts - Milan Kundera - “A magic curtain, woven of legends, hung before the world. Cervantes sent Don Quixote journeying and tore through the curtain. The world opened before the knight-errant in all the comical nakedness of its prose.― In this thought-provoking, endlessly enlightening, and entertaining essay on the art of the novel, renowned author Milan Kundera suggests that “the curtain― represents a ready-made perception of the world that each of us has—a pre-interpreted world. The job of the novelist, he argues, is to rip through the curtain and reveal what it hides. Here an incomparable literary artist cleverly sketches out his personal view of the history and value of the novel in Western civilization. In doing so, he celebrates a prose form that possesses the unique ability to transcend national and language boundaries in order to reveal some previously unknown aspect of human existence. file download xefo.pdf Life Is Elsewhere - The author initially intended to call this novel The Lyrical Age. The lyrical age, according to Kundera, is youth, and this novel, above all, is an epic of adolescence; an - ISBN:0060997028 - Jul 25, 2000 - 432 pages - Fiction - Milan Kundera, Aaron Asher Fiction - Milan Kundera - All too often, this brilliant novel of thwarted love and revenge miscarried has been read for its political implications. Now, a quarter century after The Joke was first - ISBN:9780060995058 - Feb 26, 1993 - 336 pages - The JOKE Parts Fiction - A New York Times Notable Book Irena and Josef meet by chance while returning to their homeland, which they had abandoned twenty years earlier. -

Kundera‟S Artful Exile: the Paradox of Betrayal

KUNDERA‟S ARTFUL EXILE: THE PARADOX OF BETRAYAL Yauheniya A Spallino-Mironava A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of the Arts in the Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures (Comparative Slavic Languages and Literatures) Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Hana Píchová Radislav Lapushin Christopher Putney ABSTRACT YAUHENIYA SPALLINO-MIRONAVA: Kundera‟s Artful Exile. The Paradox of Betrayal (Under the direction of Hana Píchová) The Czech novelist Milan Kundera who has lived in France since 1975 is all too familiar with betrayal, which punctuates both his life and his works. The publication of his novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being in 1984 sparked a heated debate among some of the most prominent Czech dissidents at home and leading Czech intellectuals in exile. Accusations of betrayal leveled against the author are central to the polemic, but the main area of contention addresses the larger questions of the role, rights, and freedoms of a writer of fiction, as expressed by two branches of Czechoslovak culture: exilic and dissident. By examining the dispute surrounding Kundera‟s best-known novel and tracing the trajectory of the betrayals he allegedly committed in exile, I seek to investigate the broader philosophical issue of a novelist‟s freedom, to delineate the complexities of an exilic writer‟s propensity to betray, and to demonstrate, using Kundera‟s own conception of the novel as a genre, that his betrayals are in fact positive, liberating, and felicitous. ii Table of Contents Chapters Introduction: Betrayal and Exile ..............................................................................1 I.