Lancaster, Pa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

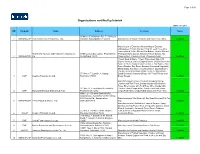

Organizations Certified by Intertek

Page 1 of 39 Organizations certified by Intertek update 30-6-2016 NO Program Name Address Certscope Status 45 Moo 1, Petchkasem Rd., T. Yaicha, A. 1 GMP&HACCP Thai Watana Rice Product Co., Ltd. Sampran Nakornpathom Thailand Manufacture of Noodle Products and Frozen Rice Stick. Certified Manufacture of Essential Oils and Natural Extracts. (Mangosteen Extract, Sompoi Extract, Leech Lime Juice Concentrated, Coffee Extract, Koi Extract, Licorice Extract, Thai-China Flavours and Fragrances Industry Co., 99 Moo 2, Lat Bua Luang, Phra Nakhon Thongpanchang Extract, Chrysanthemum Extract, Nut 2 GMP&HACCP Ltd. Si Ayutthaya 13230 Grass Extract, Pueraria Extract, Ginseng Extract) Certified Frozen Soup & Sauce, Frozen Pasteurized Egg, Chili Sauce, Ketchup, Various Dipping Sauce, Oyster Sauce and Sauce in Hermetically Sealed Container, Fish Sauce, Fish Sauce Powder, Soy Sauce Powder, Processed Vegetable, Mixed Salad, Soy Sauce, Cooking Sauce, Dipping Sauce, Vinegar & Vinegar Drinks, Salad Cream & Mayonnaise, 55 Moo. 6 T. Lumdin, A. Muang, Salad Dressing, Seasoning Paste, Oil Food Release and 3 GMP Kewpie (Thailand) Co.,Ltd. Ratchaburi 70000 Bread Spread. Certified Manufacturing of Cracker Products including Shrimp Cracker with Pork Floss, Shrimp Cracker with Chicken Floss, Rice Cracker with Pork Floss, Rice Cracker with 21 Moo 17, T.Lumlukka, A.Lumlukka, Chicken Floss, Propped Rice Cracker with Pork Floss, 4 GMP Marut and Khanom Siriphan Ltd.,Part. Phathumthani 12150 Crispy Pork Floss, Crispy Rolled Biscuit with Pork Floss Certified Office : 2/11 Bhisarn Suntornkij Rd., Sawankaloke, Sukhothai 64110 Factory: 61/4 Phichai Rd., Sawankaloke, Manufacturing of Soy Bean Oil, Soy Bean Meal and Full Fat 5 GMP&HACCP P.A.S. -

The Food Timeline

Culinary History Timeline is a listing of the culinary history timeline with article and/or information resources. http://www.foodtimeline.org/food1.html http://food.oregonstate.edu/ref/culture/ CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL ASPECTS OF FOODS (zu jedem Stichwort- entweder link / oder – Text) http://www.foodtimeline.org/foodfaqa.html Ever wonder what the Vikings ate when they set off to explore the new world? How Thomas Jefferson made his ice cream? What the pioneers cooked along the Oregon Trail? Who invented the potato chip...and why? Welcome to the Food Timeline. Food history is full of fascinating lore and contradictory facts. Historians will tell you it is not possible to express this topic in exact timeline format. They are quite right. Everything we eat is the product of culinary evolution. On the other hand? It is possible to place both foods and recipes on a timeline based on print evidence and historic context. This is what we're all about. About culinary research. P:\Frei_OltersdorfU\eTexte\Ernährungsverhalten - Daten\Ernährungsgeschichte\The food time line.doc American culinary traditions & historic surveys ---Americans at the Table: Reflections on Food and Culture, U.S. Dept. Of State ---Eating in the 20th Century, U.S.Dept. of Agriculture ---Historic American Christmas Dinner Menus ---Historic American Thanksgiving Dinner Menus ---Key Ingredients: America By Food, Smithsonian Insitution ---Not by Bread Alone: America's Culinary Heritage, Cornell Universty ---America the Bountiful, University of California at Davis ---An American Feast: Food, Dining and Entertainment in the United States (1776-1931) ---Cultural Diversity: Eating in America, Ohio State University ---Picnics in America ---School lunches ---State foods, need to cook something up for a school report? Military rations ---U.S. -

Organizations Certified by Intertek การผลิตผลิตภัณฑ์อาหารและเครื่อ

Page 1 of 40 Organizations certified by Intertek การผลติ ผลติ ภณั ฑอ์ าหารและเครอื่ งดมื่ (ISIC Code 15) update 21-04-2020 Certification NO TC Program Name Address Issue date Expiry date Status Scope number 1 83 HACCP&GMP Thai-China Flavours and Fragrances Industry Co., 99 Moo 2, Lat Bua Luang, Phra Nakhon Si Manufacture of Essential Oils and Natural Extracts. 24041107012 7th September 2018 8th September 2020 Certified (Codex) Ltd. Ayutthaya 13230 (Mangosteen Extract, Sompoi Extract, Leech Lime Juice Concentrated, Coffee Extract, Koi Extract, Licorice Extract, Thongpanchang Extract, Chrysanthemum Extract, Nut Grass Extract, Pueraria Extract, Ginseng Extract) 2 88 HACCP&GMP N.E. Agro Industry Company Limited 249 Moo 2, Ban Tanong Thown, T.Viengcom, Manufacture of Brown Sugar. 24041812004 25th March 2019 24th March 2022 Certified (Codex) A.Kumphawapi, Udonthani Province 41110 Thailand 3 113 HACCP&GMP OSC Siam Silica Co., Ltd. 6I-3A Road, Maptaphut Industrial Estate, T. MANUFACTURE OF SILICON DIOXIDE. 24040911002 11th July 2018 31st August 2021 Certified (Codex) Maptaphut, A. Muang, Rayong 21150 Thailand 4 205 HACCP&GMP P.A.S. Export & Silo Co., Ltd. Office : 2/11 Bhisarn Suntornkij Rd., Sawankaloke, MANUFACTURING OF SOY BEAN OIL. 24041411002 6th August 2017 10th August 2020 Certified (Codex) Sukhothai 64110Factory: 61/4 Phichai Rd., Sawankaloke, Sukhothai 64110 5 319 HACCP&GMP Bangkok Lab & Cosmetic Co., ltd. 48/1 Nongshaesao Road, Moo 5, Tumbon Namphu, MANUFACTURE OF DIETARY SUPPLEMENT PRODUCTS 24061502004 9th September 2019 8th September 2022 Certified (Codex) Ampur Meung, Ratchaburi 70000 Thailand (POWDER : CALCIUM, COLLAGEN AND FIBER/ TABLET : CALCIUM AND COLLAGEN/ CAPSULE : CHITOSAN) 6 510 HACCP&GMP Sahachol Food Supplies Co., Ltd. -

Divine Flavored Catering (New York) Catering Menu

Divine Flavored Catering (New York) Catering Menu Catering Menu Delivery throughout 5 boroughs plus New Rochelle & Yonkers. Delivery fees range from $35 to $100. Areas outside of this please call for delivery fee. We are now accepting Bank Transfers, Zelle, Venmo & Cashapp. Delivery Orders Must Be Picked Up Outside of The Address Given. Due to Parking Limitations We Cannot Bring Food Inside The Delivery Address. Delivery Disclosure. Mid-Manhattan to lower Manhattan $35 & higher, depending on order size. Orders above $500 a 15% delivery fee will be added to customers card at time of billing. SHIPPING NOW AVAILABLE ANYWHERE IN THE CONTINENTAL US. SHIPPING CHARGES ARE BASED ON WEIGHT AND WILL BE ADDED TO THE FINAL BILL BY THE RESTAURANT. Available: 9 am to 8 pm 7 days Order Online SHIPPING NOW AVAILABLE! WE NOW OFFER SHIPPING ANYWHERE IN THE CONTINENTAL US. SHIPPING CHARGES WILL BE BASED ON WEIGHT AND CHARGES WILL BE ADDED TO THE FINAL BILL BY THE RESTAURANT. --------------------------------------------------------- DELIVERY Delivery Orders Must Be Picked Up Outside of The Address Given. Due to Parking Limitations We Cannot Bring Food Inside The Delivery Address. ------------------------------------------------------- All Items Are Served AS IS No Modifications Allowed ------------------------------------------------------- Thanksgiving Menu ● Thanksgiving Menu 1 (Serves 10) $400 Choose 1 Appetizer; - Spiced jumbo prawns or Cream of chicken soup with French bread. 1 Salad; - Green garden salad or Baked potatoes salad. Entree; - Broiled stewed goat meat & Chicken ala orange. 1 Side; - Vegetable fried rice or Jollof rice. 1 Dessert; Fresh fruit salad or Chocolate cake. ● Thanksgiving Menu 2 (Serves 10) $400 Choice of 1 Appetizers; Meat pie / Suya (Thin sliced beef marinated in northern yajji pepper spice), or Purf purf / akara (Honey bean puree, chopped red onions, and chili with shrimp powder). -

Balanced Menus Recipe Toolkit

Welcome to the Balanced Menus Recipe Toolkit. This toolkit contains entrée recipes submitted by health care facilities across the country to assist you in providing nutritious, delicious meals to your patients, visitors, and staff as you participate in the Balanced Menus Challenge ENTRÉE RECIPES Acorn Squash with Wild Rice Pilaf Akara (Black Eyed Pea Fritters) Asparagus and Ricotta Cheese Quesadillas Baked Tilapia Fresco Bean and Kale Soup Chicken Chili with White Beans Chicken Primavera Dal Tadka Good Shepherd Chili Grilled Chicken Quinoa Pilaf Herb Crusted Trout Iranian Stuffed Tomatoes Jewish Stuffed Cabbage Rolls Organic Asian Pear Salad Oven Poached Salmon Pumpkin Chili Quinoa Garbanzo Bean Tabbouleh Seared Sea Bass over Bulgur Wheat with Lemon Vinaigrette Southwestern Stuffed Peppers Spinach Corn Casserole Tofu Steaks with Red Pepper Sauce Vegan Pasta Primavera Vegetable Tofu Stir Fry Vegetarian Meatloaf Wild Rice Mushroom Soup Whole Wheat Fettuccini with Winter Greens Enjoy these recipes as you work to create foodservice operations that are healthy for people, your community, and our environment! Developed by Members of the Sustainable Foods in Health Care taskforce A network relationship of the American Dietetic Association’s Hunger and Environmental Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group and Health Care Without Harm. Acorn Squash Stuffed with Wild Rice Pilaf Recipe provided by: Good Shepherd Health Care Center Serving size: ½ squash + ¾ C stuffing Ingredients for: 50 Servings Measurement Ingredients Acorn Squash 25 Acorn squash, cut -

The Africa Project a PROGRAM of the ASSOCIATION of YALE ALUMNI

The Africa Project A PROGRAM OF THE ASSOCIATION OF YALE ALUMNI YAMORANSA AND ACCRA, GHANA July 27 – August 7, 2012 (Extension to August 10 – North Ghana) Half NEWSLETTER June 2012 Table of Contents FUN STUFF ............................................................................................................... 1 HARD WORK ........................................................................................................... 1 CHOW TIME! ............................................................................................................ 2 ACTION ITEMS OR WHAT YOU NEED TO DO NOW! ....................................... 4 Fun stuff The purpose of this Newsletter is to let you know that iif you are in town, sometime within the next week you should receive your package of travel goodies from AYA. It should contain: - A hat - A tourbook - A Participant Directory - A bag - Two Luggage Tags - And a Packing List Please bring all the items except the packing list with you on the trip – naturally the luggage tags should be put to their proper use right away. If you have not received the package by July 1, please contact Joao at [email protected] to let him know. Hard Work Thank you to all of those, which is most of you, who have been working so hard to prepare for your projects. Today I received a long list of students – this will be amazing. I will send the list to the education and athletics groups as I soon as I know from Kwame whether we make the class sections or if they will do that. If I haven’t heard by tomorrow, I will send it as is (don’t be overwhelmed – this is opportunity!) Keep those emails flying… The Africa Project NEWSLETTER #5 June 2012 Chow Time! What kind of food will you be eating in Ghana? Wikipedia can tell you all about it with some small annotations from us… There are diverse traditional dishes from each ethnic group, tribe and clan from the north to the south and from the east to west. -

ED079230.Pdf

1110 1.4 111111-6- MICROCOPY RESOLUTIONr_TEST CHART NAION AL' BUREAU. OVSAMONIDS-1963!,- DOCUMENT RESUME ED 079 230 SP 006 016 TITLE Schools Are People..An Anthology of Stories Highlighting the Human Drama of Teaching and Learning. INSTITUTION National Education Association, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 203p. AVAILABLE FROMNEA Publication-Sales Section, 1201 Sixteenth Street, N. _W., Washington; D. C. 20036 (Stock Now 381-11960 $3.50) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 BC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Classroom Environment; *Fiction; *Literary Perspective; *Student Teacher Relationship; *Teacher Education ABSTRACT This is a collectiqn of stories written by novelists, educators, and short story writers._It is designed to allow the teacher to experience vicariously the successes and failures of their counterparts' through fiction. The stories are about students and teachers in and out of the classroom setting._Included are such noted writers as Shirley Jackson, Harper-Leer-James Michener, Claude Brown, Jesse Stuart, and others. (JB) r I FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY NOV21 1972 An Anthology of Stories Highlighting the Human Drama of Teaching and Learning From TODAY'S EDUCATION: NEA JOURNAL and Other Sources nea NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION U.5 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THISCOPY. EDUCATION A WELFARE RIGHTEO MATERIAL HAS BEENGRANTED BY NATIONAL INSTITUTEOF , EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO 14/E4 DUCE() EXACTLY AS THE PERSON OR RECEIVED FROM ATING IT POINTSORGANIZATION OF ORIGIN TO ERIC AND ORGANIZATIONS VIEW OR OPINIONS OPERATING STATED DO NOT UNOER AGREEMENTS WITH THE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONALNECESSARILY REPRE NATIONAL IN- INSTITUTE OF STITUTE OF EDUCATION. FURTHERREPRO. EDUCATION POSITIONOR POLICY RUCTION OUTSIDE THE FRIGSYSTEM RE. -

The Effect of Novel Frying Methods on Quality of Breaded Fried Foods

The Effect of Novel Frying Methods on Quality of Breaded Fried Foods Rhonda Bengtson Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Biological Systems Engineering Parameswarakumar Mallikarjunan, Chair John S. Cundiff George J. Flick, Jr. July 17, 2006 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: pressure frying, vacuum frying, fish sticks, nitrogen gas, compressed air ©2006 Rhonda Bengtson The Effect of Novel Frying Methods on Quality of Breaded Fried Foods By Rhonda Bengtson Parameswarakumar Mallikarjunan, Chair Biological Systems Engineering ABSTRACT Fried foods are popular around the world. They are also high in fat and considered unhealthy by many people. Reducing the fat content of fried food may allow for even more growth in their popularity, while allowing for healthier eating. Furthermore, vacuum-frying and frying with nitrogen gas have both been shown to extend the life of frying oil. In this study, the use of novel frying methods as a way to reduce fat content of breaded fried foods was evaluated. A pressure fryer was modified so that fish sticks could be vacuum-fried and fried using external gas (nitrogen and compressed air) as the pressurizing media. These products were compared to those pressure fried and fried atmospherically in terms of crust color, moisture content, oil content, texture, and juiciness. Overall, products fried using nitrogen and air were not found to be significantly different (p < 0.05) from each other. These products were both more tender and lower in oil content than steam-fried fish sticks. -

Teenage Murder Suspects Still at Large by Sompratch Saowakhon Single Arrest Warrant for All Four All Four Are Suspects in the Mit Murder in the Case

Volume 14 Issue 8 News Desk - Tel: 076-236555February 24 - March 2, 2007 Daily news at www.phuketgazette.net 25 Baht The Gazette is published in association with Island-wide security IN THIS ISSUE NEWS: Swiss man stabs po- CCTV now online lice; Two die in head-on By Janyaporn Morel smash. Pages 2 & 3 INSIDE STORY: Patong Beach PHUKET: The next time you are masseuse set ablaze in having a night out on the town in broad daylight. Patong, Kata-Karon or Phuket Pages 4 & 5 City be sure to keep a smile on your face: you might be on TV. AROUND THE NATION: To Don Col Peerayuth Karachedi, Muang or not to Don Muang? Superintendent for Administrative Airlines are divided. Page 8 Affairs at Phuket Provincial Po- AROUND THE SOUTH: More lice Station, told the Gazette on than 30 bombs ring in the February 14 that a closed-circuit Chinese New Year in the television (CCTV) system has Deep South. Page 9 been fully tested and is now op- erational in the three popular PEOPLE: Club diva Barbara Tucker belts out her famous tourist locations. anthems in the name of Love. Each of the three locales Pages 14 & 15 has 16 cameras linked to a com- mand center at a local police sta- AMBROSIA’S SECRETS: Fishing tion in Kathu, Chalong and for compliments nets few re- Phuket City, respectively. sults. Page 17 Installed under a 16-million- WATCHERS WATCHING: Worawit Worrawiboonpong, Manager of CAT Telecom’s Phuket Office, shows LIFESTYLE: Strap-ons and slip- baht contract with telecommuni- cations provider CAT Telecom off the capabilities of the new high-tech surveillance system to Phuket City Police Superintendent Col ons – shoes; U2’s latest Nos Svettalekha at the Phuket City Police Station CCTV Command Center. -

Mmmmmmmmmmsmm NW

. mmmmmmmmmmsmm ftO Mr - V y mm MP-- Established July , 1856. Iinvnr ttt t . L, 1 "AWAUAN ISLANDS, WEDNESDAY. MAY iom n,f,TA- TM T www. VV u V i All tl I ' PBICE FIVX1 .... i ft DMZ13 I'M ifn.iant corporation wn. .k An0.1NKY3. I.f yt?JMay,..1J00' enraed in the business interests of corporations. Is EY frt-iKh- t n It generally FOR for Mrl?rllnK Pa""K"s and admitted that bribery and corruption . m A JL'I'i-- ' Atkinson upon by rife are Jr.-On- everywhere, Vw IN - that there is scarcely a j nil over ? The defendants department "'''(' Merchant ereforri0oraU0n- are in the average city govern '""'. Btruct ou!0 " carr". and I o In- - nunt that will bear investigation, that SEEN IN blackmail and the sale of law are com- -- Jwi LOU to the oonclualon from mon things. Law - . cimf the puts a penalty on vd i v. C Arhl l-- ,,s, unl V1 tn.e th ay of April Maladministration of ,J ...... - No. j 9 iu law on the part of (!. Wnt M1N ..r! :pJa'rtift Peered himself hi a fit anc hose in authority puts a premium on STRELS r.Tn.-i- ue on D it .i board the AiW.rquirfs. 8aloons in most of our Miowera. one of tnft Htwinwri c ORRU to be - I of closed , i: n"v to l;ms. v.'1"1, corl,orat'on. Malkdmfn-rre- ,'. from Honolu- Sundays. m , lu to v . tt. Ictoria, stranonV 1 TOR Krt other port), Hritlh Columbia, and ?h laW prants absolution NW ( u. -

During the Deep-Frying of Akara, Traditional Cowpea-Paste Balls, in Brazil

GRASAS Y ACEITES 70 (2) April–June 2019, e305 ISSN-L: 0017-3495 https://doi.org/10.3989/gya.0703182 A real case study on the physicochemical changes in crude palm oil (Elaeis guineensis) during the deep-frying of akara, traditional cowpea-paste balls, in Brazil S. Feitosaa, E.F. Boffob, C.S.C. Batistab, J. Velascoc, C.S. Silvaa, R. Bonfima and D.T. Almeidaa,* aSchool of Nutrition, Federal University of Bahia - UFBA, Av. Araújo Pinho 32, 40110-150, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. bDepartment of Organic Chemistry, Institute of Chemistry, Federal University of Bahia – UFBA, 40170-290, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. cInstituto de la Grasa, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Campus Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Ctra. de Utrera km 1, E-41013 Sevilla, Spain. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Submitted: 02 July 2018; Accepted: 16 October 2018; 18 February 2019 SUMMARY: The objective of this study was to evaluate the physicochemical changes in crude palm oil during a real case of deep-frying ofa akar, cowpea-paste balls, fried and sold in the streets o f Brazil. Discontinuous frying over five consecutive days, using 5-h frying a day, was performed according to traditional practices. The formation of polar compounds was evaluated by the IUPAC official method and by quick tests based on mea- sures of physical properties, Testo 270 and Fri-check. In addition, 1H-NMR spectroscopy was applied to evalu- ate physicochemical changes. The results showed that after 15-h frying the total content of polar compounds (TPC) exceeded the limit of 25% established in most of the recommendations and regulations on heated oils. -

A Symphony of Flavors

A Symphony of Flavors A Symphony of Flavors: Food and Music in Concert Edited by Edmundo Murray A Symphony of Flavors: Food and Music in Concert Edited by Edmundo Murray This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Edmundo Murray and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7726-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7726-8 CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................................... vii Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction: Singing while Sowing Edmundo Murray Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 17 The Deliriously Tempting Complementarity of Syrian Food and Music Rihab Kassatly Bagnole Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 46 Music as the Food of Longing in Ireland and Irish America Sean Williams Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 65 Classical