ED079230.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gazette a Bounty an Escapee from Meet GCHS’S of Berries Scudder’S Pond? Valedictorian Page 15 Page 18 Page 6 Vol

HERALD________________ GLEN COVE _______________ Gazette A bounty An escapee from Meet GCHS’s of berries Scudder’s Pond? valedictorian Page 15 Page 18 Page 6 Vol. 28 No. 24 JUNE 13-19, 2019 $1.00 Is clean water in sight for Crescent Beach? By MIKE CoNN $200,000. gested solutions have involved [email protected] Past studies have concluded the installation of filters in the that the contamination comes pipes to clean the water as it Crescent Beach’s public acces- from runoff that finds its way flows through them. Last year, sibility — or lack of it — has been into pipes leading to Crescent DeRiggi-Whitton discussed differ- a source of frustration for many Beach. Water flowing through ent means of cleaning up the Glen Covers for the past decade. stream with Eric Swenson, exec- The beach was closed in 2009 due utive director of the Hempstead to bacterial contaminants in the Harbor Committee, and Dr. Sarah stream that empties out there. etlands are Meyland, an associate professor Although the level of contamina- naturally a water at the New York Institute of Tech- tion has fluctuated over the years, W nology and the director of the there have been instances when filter system. As water school’s Center for Water the concentration of bacteria in Resources Management. the stream has been over 1,000 migrates through a According to Meyland, com- times higher than what is munities across the country are deemed safe for humans. wetland, water quality is working to improve water quality A number of studies have improved. -

Nashville Daily Union, April-July 1862 Vicki Betts University of Texas at Tyler, [email protected]

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler By Title Civil War Newspapers 2016 Nashville Daily Union, April-July 1862 Vicki Betts University of Texas at Tyler, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/cw_newstitles Recommended Citation Betts, ickV i, "Nashville Daily Union, April-July 1862" (2016). By Title. Paper 101. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/738 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Civil War Newspapers at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in By Title by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NASHVILLE DAILY UNION April 13, 1862-July 31, 1862 NASHVILLE DAILY UNION, April 13, 1862, p. 3, c. 2 Remember—that at the Capitol Bakery, Restaurant and Family Grocery, 18 Cedar Street, Tennessee money is taken at par for Bread, family groceries of all descriptions, the best in the world. Everything in the eating line got up in the best style by one of the best cooks in the world. Ice Cream—that is, the ne plus ultra of this delightful luxury—fresh trout, choice Butter, superfine flour, at prices as low down as if you paid Gold. April 8—1w. NASHVILLE DAILY UNION, April 13, 1862, p. 3, c. 6 Union Feeling in Tennessee.—An officer of Col. Pope's Fifteenth Kentucky Regiment, writing to his brother in this city and describing its entrance into the town of Shelbyville, Bedford county, Tenn., gives the following glowing and cheering account of the loyalty of the inhabitants.—Louisville Journal. -

(Muise)\15-274 Amicus Brief Priests for Life.Wpd

NO. 15-274 In the Supreme Court of the United States WHOLE WOMAN’S HEALTH, et al., Petitioners, v. JOHN HELLERSTEDT, M.D., COMMISSIONER, TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF STATE HEALTH SERVICES, et al., Respondents. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE PRIESTS FOR LIFE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS ROBERT JOSEPH MUISE Counsel of Record American Freedom Law Center P.O. Box 131098 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48113 (734) 635-3756 [email protected] DAVID YERUSHALMI American Freedom Law Center 1901 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Suite 201 Washington, D.C. 20006 (855) 835-2352 Counsel for Amicus Curiae Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................... i STATEMENT OF IDENTITY AND INTERESTS OF AMICUS CURIAE PRIESTS FOR LIFE ...... 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ............. 3 ARGUMENT............................... 3 I. Texas Has a Legitimate Basis to Regulate Abortion in order to Minimize Its Harmful Effects.................................. 3 II. The Testimonies of Abortion Victims Demonstrate that More Abortion Regulations Are Needed, not Less...................... 5 CONCLUSION ............................ 13 APPENDIX Silent No More Testimonies ............App. 1 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CASES Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992) ............. 3, 4, 5 OTHER AUTHORITIES http://www.silentnomoreawareness.org/testimonies /index.aspx.............................. 6 Senate Comm. on Health -

Les Mis, Lyrics

LES MISERABLES Herbert Kretzmer (DISC ONE) ACT ONE 1. PROLOGUE (WORK SONG) CHAIN GANG Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye Look down, look down You're here until you die. The sun is strong It's hot as hell below Look down, look down There's twenty years to go. I've done no wrong Sweet Jesus, hear my prayer Look down, look down Sweet Jesus doesn't care I know she'll wait I know that she'll be true Look down, look down They've all forgotten you When I get free You won't see me 'Ere for dust Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye. !! Les Miserables!!Page 2 How long, 0 Lord, Before you let me die? Look down, look down You'll always be a slave Look down, look down, You're standing in your grave. JAVERT Now bring me prisoner 24601 Your time is up And your parole's begun You know what that means, VALJEAN Yes, it means I'm free. JAVERT No! It means You get Your yellow ticket-of-leave You are a thief. VALJEAN I stole a loaf of bread. JAVERT You robbed a house. VALJEAN I broke a window pane. My sister's child was close to death And we were starving. !! Les Miserables!!Page 3 JAVERT You will starve again Unless you learn the meaning of the law. VALJEAN I know the meaning of those 19 years A slave of the law. JAVERT Five years for what you did The rest because you tried to run Yes, 24601. -

The Godiva Effect a Woman's Reflections on Engineering at the University of Alberta

The Godiva Effect A Woman's Reflections on Engineering at the University of Alberta by Mildred Lau for Dr. Amy Kaler SOC 301: Sociology of Gender University of Alberta 11. March 2009 The Godiva Effect Mildred Lau (1091348) 1/9 Foreword: In the Beginning I began my university career in the Faculty of Engineering, and spent two-and-a-half years there1. It was not only because of my strength in math and physics that I chose engineering, but also because of cultural expectations. I had no idea what an engineer did. I could argue that I still don't know. But I had had mostly male friends in high school, and I expected that I could navigate the social life and the student image in the same way. Boy, was I wrong. Why did I leave engineering? Why did I not just “suck it up” and keep going? I think that factors involved included that engineering turned out to be nothing that I really wanted in terms of career prospects as well as the highly gendered environment which I describe below. I felt that it was better for my sanity and my productivity to choose a career goal that could utilize my overall abilities rather than a select few. It is not an experience that I regret having been through, and I try not to get too angry and rant too much about it, but of course there will be some (possibly unfair) generalizations... Looking Out and Looking In I was not aware of any WISEST or women-in-math-and-science programming that was available at my high school, so I signed up to study engineering, quite literally, “sight unseen.”2 Fortunately, for those not quite sure what engineering is after entering the program, an information seminar course is given throughout the first year. -

Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020

k Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020 For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk CONTENTS 5 USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS 5 EXPLANATION OF KASHRUT SYMBOLS 5 PROBLEMATIC E NUMBERS 6 BISCUITS 6 BREAD 7 CHOCOLATE & SWEET SPREADS 7 CONFECTIONERY 18 CRACKERS, RICE & CORN CAKES 18 CRISPS & SNACKS 20 DESSERTS 21 ENERGY & PROTEIN SNACKS 22 ENERGY DRINKS 23 FRUIT SNACKS 24 HOT CHOCOLATE & MALTED DRINKS 24 ICE CREAM CONES & WAFERS 25 ICE CREAMS, LOLLIES & SORBET 29 MILK SHAKES & MIXES 30 NUTS & SEEDS 31 PEANUT BUTTER & MARMITE 31 POPCORN 31 SNACK BARS 34 SOFT DRINKS 42 SUGAR FREE CONFECTIONERY 43 SYRUPS & TOPPINGS 43 YOGHURT DRINKS 44 YOGHURTS & DAIRY DESSERTS The information in this guide is only applicable to products made for the UK market. All details are correct at the time of going to press but are subject to change. For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk. Sign up for email alerts and updates on www.kosher.org.uk or join Facebook KLBD Kosher Direct. No assumptions should be made about the kosher status of products not listed, even if others in the range are approved or certified. It is preferable, whenever possible, to buy products made under Rabbinical supervision. WARNING: The designation ‘Parev’ does not guarantee that a product is suitable for those with dairy or lactose intolerance. WARNING: The ‘Nut Free’ symbol is displayed next to a product based on information from manufacturers. The KLBD takes no responsibility for this designation. You are advised to check the allergen information on each product. k GUESS WHAT'S IN YOUR FOOD k USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS Hi Noshers! PRODUCTS WHICH ARE KLBD CERTIFIED Even in these difficult times, and perhaps now more than ever, Like many kashrut authorities around the world, the KLBD uses the American we need our Nosh! kosher logo system. -

Thoughts... in This Issue >>> Finding an Agent That’S Right for You Transformation VBS Pictures and Thanks Great News and a Little Fun

JULY 2014 final thoughts... in this issue >>> Finding An Agent That’s Right For You Transformation VBS Pictures and Thanks Great news and a Little Fun Blakemore 4.0 Updates Online 4.0 Update Everything you wanted to know about Blakemore 4.0 is always available at http://jody.populr.me/blakemore-4-update Blakemore Staff Reminders of a couple of recent developments: Pastor: Monthly Edition The Trustees have determined that a six-figure investment in new HVAC is not in the Matthew Charlton church's best interests. Because of that, the option of Blakemore 4.0 continuing in its cur- ([email protected]) rent facility beyond a couple of years is now off the table. Our next options move to re- building at 3601 West End or moving to a new location (to be determined). Minister to Families: Gracie Dugan The Building Committee (aka Trustees) are also conducting a number of listening sessions ([email protected]) to help discern the priorities for a smaller, more efficient facility. These will continue through June to involve as many people as possible and ensure that the voice of the entire congregation is at the center of this conversation. Music Director: Beth Holzemer We are in the initial stages of drafting a Request For Proposal (RFP), which will go to de- ([email protected]) velopers to solicit their bids and ideas for the property. We expect this document to be ready by July. You can also view a current timeline at the website. Administrative Assistant: Steffie Misner IMPORTANT! Meanwhile, we as a congregation must address our urgent need to grow Blake- ([email protected]) In this sense, the Methodist way is to live within more - a couple Sundays back, Gracie preached a powerful sermon from Ezekiel about the re- Blakemore folks, we are in the middle of an in- newed life that is possible through God, even in "dem dry bones”. -

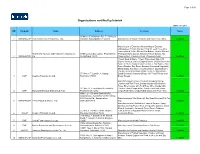

Organizations Certified by Intertek

Page 1 of 39 Organizations certified by Intertek update 30-6-2016 NO Program Name Address Certscope Status 45 Moo 1, Petchkasem Rd., T. Yaicha, A. 1 GMP&HACCP Thai Watana Rice Product Co., Ltd. Sampran Nakornpathom Thailand Manufacture of Noodle Products and Frozen Rice Stick. Certified Manufacture of Essential Oils and Natural Extracts. (Mangosteen Extract, Sompoi Extract, Leech Lime Juice Concentrated, Coffee Extract, Koi Extract, Licorice Extract, Thai-China Flavours and Fragrances Industry Co., 99 Moo 2, Lat Bua Luang, Phra Nakhon Thongpanchang Extract, Chrysanthemum Extract, Nut 2 GMP&HACCP Ltd. Si Ayutthaya 13230 Grass Extract, Pueraria Extract, Ginseng Extract) Certified Frozen Soup & Sauce, Frozen Pasteurized Egg, Chili Sauce, Ketchup, Various Dipping Sauce, Oyster Sauce and Sauce in Hermetically Sealed Container, Fish Sauce, Fish Sauce Powder, Soy Sauce Powder, Processed Vegetable, Mixed Salad, Soy Sauce, Cooking Sauce, Dipping Sauce, Vinegar & Vinegar Drinks, Salad Cream & Mayonnaise, 55 Moo. 6 T. Lumdin, A. Muang, Salad Dressing, Seasoning Paste, Oil Food Release and 3 GMP Kewpie (Thailand) Co.,Ltd. Ratchaburi 70000 Bread Spread. Certified Manufacturing of Cracker Products including Shrimp Cracker with Pork Floss, Shrimp Cracker with Chicken Floss, Rice Cracker with Pork Floss, Rice Cracker with 21 Moo 17, T.Lumlukka, A.Lumlukka, Chicken Floss, Propped Rice Cracker with Pork Floss, 4 GMP Marut and Khanom Siriphan Ltd.,Part. Phathumthani 12150 Crispy Pork Floss, Crispy Rolled Biscuit with Pork Floss Certified Office : 2/11 Bhisarn Suntornkij Rd., Sawankaloke, Sukhothai 64110 Factory: 61/4 Phichai Rd., Sawankaloke, Manufacturing of Soy Bean Oil, Soy Bean Meal and Full Fat 5 GMP&HACCP P.A.S. -

BAY COLT Barn 27 Hip No

Consigned by Hunter Valley Farm, Agent Hip No. BAY COLT Barn 318 Foaled May 28, 2016 27 Hennessy Johannesburg .................. Myth Scat Daddy ........................ Mr. Prospector Love Style ........................ Likeable Style BAY COLT Northern Dancer El Gran Senor .................... Sex Appeal High Walden .................... (1997) Roberto Modena ............................ Mofida (GB) By SCAT DADDY (2004). Black-type winner of $1,334,300, Florida Derby [G1] (GP, $600,000), etc. Leading sire 4 times in Chile, sire of 7 crops of racing age, 950 foals, 685 starters, 84 black-type winners, 507 winners of 1570 races and earning $48,770,911, 11 champions, including Dacita (CHI) ($1,052,769, Diana S. [G1] (SAR, $300,000), etc.), Il Campione (CHI) ($384,594, El Ensayo MEGA Chilean Derby [G1] , etc.), Solaria (CHI) ($255,591, El Derby [G1] , etc.), and of Lady Aurelia [G1] (hwt., $718,617). 1st dam HIGH WALDEN , by El Gran Senor. Winner at 2, £34,977, in England, 2nd Voda - fone Victress S., Oh So Sharp S., 3rd Tattersalls Musidora S. [G3] ; winner at 3 and 4, $196,671, in N.A./U.S., Matiara S. [L] (HOL, $90,000), 2nd Santa Ana H. [G2] . (Total: $250,620). Dam of 9 other registered foals, 9 of racing age, including a 2-year-old of 2017, 5 to race, 4 winners, including-- Razorbill (g. by Speightstown). 2 wins at 3, £15,662, in England; 8 wins, 6 to 8, 2017, $97,313, in N.A./U.S. (Total: $122,391). 2nd dam MODENA, by Roberto. Unraced. Half-sister to ZAIZAFON -G3 , Factual [G1] (Total: $59,515, sire, Dangora [G2] , Magnified . -

Land of Legends (IRE)

equineline.com Product 40P 01/21/21 12:56:37 EST Land Of Legends (IRE) Dark Bay or Brown Horse; Feb 19, 2016 Gone West, 84 b Zafonic, 90 b Zaizafon, 82 ch =Iffraaj (GB), 01 b Nureyev, 77 b Land Of Legends (IRE) =Pastorale (GB), 88 ch Park Appeal (IRE), 82 dk b/ Foaled in Ireland $In the Wings (GB), 86 b $Singspiel (IRE), 92 b =Homily (GB), 08 ch Glorious Song, 76 b Lahib, 88 dk b/ =Last Resort (GB), 97 ch =Breadcrumb (GB), 82 ch By IFFRAAJ (GB) (2001). Stakes winner of $695,587 USA in England, Betfair Cup Lennox S. [G2], etc. Sire of 12 crops of racing age, 2168 foals, 1441 starters, 72 stakes winners, 2 champions, 865 winners of 2370 races and earning $59,348,517 USA, including Turn Me Loose (Champion twice in New Zealand, $1,178,693 USA, Emirates S. [G1], etc.), Helal's Gold (Champion twice in Greece, $21,608 USA), Ribchester (IRE) (Hwt. 6 times in Europe, England and France, $3,503,680 USA, Prix du Haras de Fresnay-Le-Buffard - Jacques Le Marois [G1], etc.), Jungle Cat (Hwt. in United Arab Emirates, $1,794,385 USA, Azizi Developments Al Quoz Sprint [G1], etc.), Rizeena (Hwt. in Ireland, $1,035,044 USA, Coronation S. [G1], etc.). 1st dam =HOMILY (GB), by $Singspiel (IRE). Unraced in Great Britain. Dam of 5 foals, 4 to race, 3 winners-- Land Of Legends (IRE) (c. by =Iffraaj (GB)). See below. =Monologue (IRE) (g. by =Manduro (GER)). Winner at 4 in ENG, $3,098 (USA). -

The Food Timeline

Culinary History Timeline is a listing of the culinary history timeline with article and/or information resources. http://www.foodtimeline.org/food1.html http://food.oregonstate.edu/ref/culture/ CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL ASPECTS OF FOODS (zu jedem Stichwort- entweder link / oder – Text) http://www.foodtimeline.org/foodfaqa.html Ever wonder what the Vikings ate when they set off to explore the new world? How Thomas Jefferson made his ice cream? What the pioneers cooked along the Oregon Trail? Who invented the potato chip...and why? Welcome to the Food Timeline. Food history is full of fascinating lore and contradictory facts. Historians will tell you it is not possible to express this topic in exact timeline format. They are quite right. Everything we eat is the product of culinary evolution. On the other hand? It is possible to place both foods and recipes on a timeline based on print evidence and historic context. This is what we're all about. About culinary research. P:\Frei_OltersdorfU\eTexte\Ernährungsverhalten - Daten\Ernährungsgeschichte\The food time line.doc American culinary traditions & historic surveys ---Americans at the Table: Reflections on Food and Culture, U.S. Dept. Of State ---Eating in the 20th Century, U.S.Dept. of Agriculture ---Historic American Christmas Dinner Menus ---Historic American Thanksgiving Dinner Menus ---Key Ingredients: America By Food, Smithsonian Insitution ---Not by Bread Alone: America's Culinary Heritage, Cornell Universty ---America the Bountiful, University of California at Davis ---An American Feast: Food, Dining and Entertainment in the United States (1776-1931) ---Cultural Diversity: Eating in America, Ohio State University ---Picnics in America ---School lunches ---State foods, need to cook something up for a school report? Military rations ---U.S. -

10-Inch Contractor Table Saw 36-725 T2

10-inch Contractor Table Saw Scie de table de 10 pouces (254 mm) pour entrepreneurs Sierra de mesa de 10 pulgadas (254 mm) para contratista Français (32) Español (61) www.DeltaMachinery.com Instruction Manual Manuel d’utilisation Manual de instrucciones 36-725 T2 To reduce risk of serious injury, thoroughly read and comply with all warnings and instructions in this manual and on product. KEEP THIS MANUAL NEAR YOUR SAW FOR EASY REFERENCE AND TO INSTRUCT OTHERS TABLE OF CONTENTS IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS ..............................3 OPERATION ........................................................................20 SAFETY LOGOS ..................................................................3 Starting and Stopping the Saw ..........................................20 GENERAL POWER TOOL SAFETY RULES ...........................4 Overload Protection ..........................................................21 TABLE SAW SAFETY RULES ...............................................5 Making Cuts.....................................................................21 POWER CONNECTIONS .....................................................7 Rip Cuts .........................................................................22 Power Source ................................................................ 7 Bevel Rip Cuts ................................................................22 Grounding Instructions ................................................... 7 Cross-Cuts ......................................................................23