A Symphony of Flavors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DINNER MENU HUMMUS YOUR WAY DELUXE PLATTERS Served with Three Pitas Deluxe Platers Served with Hummus, Baba Ganough, Tahini Salad, Israeli Salad, Two Pitas

ALLAN’S FALAFEL DINNER MENU HUMMUS YOUR WAY DELUXE PLATTERS Served with three pitas Deluxe platers served with hummus, baba ganough, tahini salad, Israeli salad, two pitas. a choice of rice, red cabbage or fries. Classic Hummus: $6.95 Galit Hummus: $8.95 Allan's Famous Falafel Deluxe Platter: $18 Classic hummus topped with pickles, zatar, paprika, and olive. Our famous ground chickpeas, combined with spices, then formed into small balls. Hummus with Falafel: $9.95 Classic hummus served with falafel. Chicken Cutlet Delux Platter: $20.95 Seasoned chicken breast with onions and peppers, Hummus with Shawarma: $10.95 cooked on the grill. Layers of lamb and turkey, slowly roasted on a vertical grill, sliced thinly, served with classic hummus. Chicken Kebab Delux Platter: $21.95 Chicken cubes on a skewer, cooked on a charcoal grill. Hummus with Chicken Cutlet: $10 Seasoned chicken breast with onions and peppers, Kufta Kebab Delux Platter: $21.95 cooked on a grill, served with classic hummus. Minced ground beef and lamb, seasoned with spices, onion, parsley. APPETIZERS Turkey Shawarma Deluxe Platter: $22.95 Falafel (4 Balls): $3.50 Layers of lamb and turkey, slowly roasted on a vertical Chickpeas ground with parsley, cilantro, spices, formed into roasting grill, served in thin slices. balls and deep fried. - Mixed Grill Deluxe Platter: $26.95 Chicken, shawarma and kufta kebab. Stuffed Grape Leaves: 4 pieces: $5 8 pieces: $8.50 Rice, vegetables, spices, rolled in grape leaves. PLATE ENTREES Tzatziki Dip: small: $5.50 med: $7.50 Plates are served with green salad, hummus, tahini salad, Yogurt, cucumber, olive oil, fresh herbs. -

Point. Click. Eat. Dineinonline.Com

Point. Click. Eat. dineinonline.com 1 Questions & Answers What is Dine-In? What about drinks? We are a service that allows you to get food deliv- We offer a large variety of sodas in cans or 6-packs. ered from Michiana’s best restaurants! Place your We also offer lemonade, iced tea and bottled water. order with our service and we will make arrange- See back cover for a full drink menu. ments for the restaurant to prepare it and for a driver to deliver it! What hours are you open? How do I order? LUNCH Look through the menus in this book, then call us at (574) 675-9999. A friendly order taker will answer MONDAY - FRIDAY 10:00AM - 2:00PM the phone and guide you through the ordering pro- DINNER cess. Alternatively, visit our website to place your order online: www.dineinonline.com MONDAY - THURSDAY 4:00PM - 10:00PM FRIDAY 4:00PM - 10:30PM How much does it cost? SATURDAY 3:00PM - 10:30PM The restaurants ask that you order a minimum of SUNDAY 3:00PM - 9:00PM $10 worth of food. Restaurant food prices are the same as they would be if you picked up the order What restaurants are available? yourself*. We add a minimal delivery fee, which covers your entire order, no matter how big or Aladdin’s Eatery ..................................................................4 small. Menus and prices are subject to change at Barnaby’s Pizza .................................................................61 any time. To view the most up-to-date menus, visit Beef ‘O’ Brady’s ................................................................14 our website. Between -

Hummus• Falafel•Shawarma•Gyros Shish Kabab • Gourmet Burgers

Kids Menu Beverages For 10 and under kids only please! Limonana All Kids meals served with a choice of Fresh made Lemonade with fresh mint. French fries OR rice OR Israeli salad, Fresh and a small juice OR Arrowhead water. Turkish Coffee Cooked over stove top in Ibrik. Kids size Grilled Burger Espresso, Cappuccino, Latte Grilled 1/4 lb. 100% all beef burger. Served plain in a bun. With Cheddar cheese add 99¢ Hot Tea, Hot Coffee & Decaf Kids size Schnitzel Strips plate * Crispy pan fried breaded chicken breast strips. Ice Tea & Ice Coffee GF Kids size Chicken Shish Kabab plate * San Pellegrino Grilled cubes of marinated chicken breast. Mineral Water & Soda GF Balanced • Delicious • Healthy! Kids size Chicken Shawarma Plate * Bottled Spring Water Thin slices of marinated chicken. Kids size Gyros Plate * Snapple, Honest Tea Thin slices of Gyros strips and Tzatziki sauce. Orangina, Fiji Water Kids size Falafel Plate * Hummus • Falafel • Shawarma • Gyros 3 Falafel with 2oz. Tahini Sauce. Mex Coke & Jarritos * Add our delicious pita to any plate for $1.50 Malt Star (“black beer”) Select Soda Cans Shish Kabab • Gourmet Burgers Wine Desserts House wines by the glass • Quality Meats • Select wine bottles Baklava Beer Vegan, Vegetarian & Gluten Free Dishes Sweet Fillo Pastry with nuts. Select Domestic and Imported Beers We cater for all occasions and all allergies Lunch & Dinner Menu Hours: Monday - Thursday 11:00 AM - 8:00 PM Friday & Saturday 11:00 AM - 8:30 PM Sunday 11:00 AM - 3:00 PM Dine-In Take-Out Catering Tel: 925 297 6343 Www.Kabab-Burger.com 3647 Mt. -

Set Lunch & Buffet Selection16052014re

COFFEE BREAKS, SET LUNCH & BUFFET LUNCHES 2014 COFFEE BREAKS PAGE 3 LUNCH PAGE 8 FAMILY STYLE SELECTION PAGE 10 BUFFET SELECTION PAGE 14 Prices in this document are for 2014 and quoted in Thai Baht. These prices cannot be used beyond 2014, but the menus and content can act as an indication. COFFEE BREAKS, SET LUNCH & BUFFET LUNCHES Coee Breaks PAGE 2 COFFEE BREAKS, SET LUNCH & BUFFET LUNCHES COFFEE BREAKS Coee Breaks (Please tick) To be chosen from the coee breaks menu selection THB 370* 2x Savoury, 3x Sweet, 2 x Juice THB 425 3x Savoury, 3x Sweet, 2 x Juice THB 475 4x Savoury, 4x Sweet, 3 x Juice All the above include coffee & tea, red & green apples THEME COFFEE BREAKS (minimum of 50 persons & up, rate per person per break) DESCRIPTION RATE Ice Breaker Mango Mania Jungle Break 550 Thai Herbal Spa & Massage Break Phuket Fantasy BREAKFAST DESCRIPTION RATE Thai Buet Breakfast: minimum of 80 persons 470 Japanese Buet Breakfast: minimum of 80 persons 600 American Buet Breakfast: minimum of 80 persons 600 *Selection of the meeting package The above prices are quoted in Thai Baht (unless otherwise specified) and inclusive of 10% service charge and 7% government tax. Prices are non-commissionable. PAGE 3 COFFEE BREAKS, SET LUNCH & BUFFET LUNCHES SAVOURY European / Western selection Caesar salad wrap (V) Bbq chicken wings with tangy ranch sauce Pastrami and coleslaw on rye bread sandwich Deep fried sh nger with Cajun dipping sauce Smoked salmon nger sandwich Mini chicken fajita with guacamole Mini tomato and cheese ciabatta (V) Quiche Lorraine -

Aladdins-Nutritional-Info.Pdf

The purpose of this analysis is to assist you in making the right food choices for your personal needs. All nutrition information is based on the entire plate served. Please note the generous portion sizes of our dishes; in the spirit of Lebanese tradition, many of our dishes are intended to be shared. Take home containers are available if you wish to limit your intake and save a portion of your meal for another time. APPETIZERS Serving Calories Total Fat Sat. Fat Trans Fat Chol Sodium Potassium Carb Fiber Sugars Protein Size (g) (g) (g) (mg) (mg) (mg) (g) (g) (g) (g) Hummus - Small 8oz 418 23 3 0 0 1344 - 43 11 7 16 Hummus - Regular 18oz 608 32 4 0 0 2006 - 65 16 11 24 Hummus - Large 26oz 1216 64 9 0 0 4010 - 129 33 21 48 Tabouli - Small 4oz 204 19 3 0 0 440 335 9 3 2 2 Tabouli - Regular 9oz 403 37 5 0 0 847 670 18 5 5 4 Tabouli - Large 13oz 602 56 8 0 0 1255 1005 26 7 7 6 Baba Gannouj - Small 8oz 357 28 4 0 0 1264 - 26 6 5 9 Baba Gannouj - Regular 12oz 516 39 6 0 0 1901 - 39 9 8 14 Baba Gannouj - Large 24oz 1031 78 11 0 0 3801 - 77 17 17 27 Spicy Cauliflower 9oz 140 11 2 0 0 910 - 9 5 4 4 Foole M Damas - Small 7oz 297 24 3 0 0 1037 360 15 5 5 6 Foole M Damas - Regular 14oz 749 66 9 0 0 2071 648 31 9 8 13 Loubie - Small 8oz 135 8 1 0 0 558 389 12 3 5 3 Loubie - Regular 11oz 206 11 2 0 0 976 680 21 6 9 5 Falafel - Small 5.5oz 360 14 2 0 2 1725 724 45 9 10 17 Falafel - Regular 10oz 528 17 2 0 2 2714 1291 74 15 17 26 Dawali - Small 10oz 541 37 5 0 2 1057 881 46 8 10 11 Dawali - Regular 25oz 1090 75 11 0 6 2148 1770 92 16 19 22 Kibbie 12oz 831 60 13 1 69 1265 816 51 8 10 27 Sambusek 11oz 628 21 4 0 160 580 654 70 6 9 39 Fatayer 7oz 341 4 2 0 13 540 757 63 5 4 13 Sfiha 13oz 677 26 9 1 102 1587 1001 63 4 9 41 Vegetarian Combo 27oz 1293 72 10 0 2 4582 2294 113 22 26 45 SOUP Serving Calories Total Fat Sat. -

Delisky — VIP Jet Catering Menu

DeliSky — VIP Jet Catering Menu AIRPORT ORDER DETAILS Portugal, Lisbon Delivery Date: Delivery Time (LT): CONTACT A/C Registration: [email protected] Handling: +41 44 586 31 10 Heating Equipment: Name: Phone: Email: Bulk or ready to serve? BREAKFAST & BAKERY BREAD QTY Bread Rolls, per piece White Bread Roll, per piece Brown Bread Roll, per piece Large French Baguette, per piece White Sliced Bread Loaf Brown Sliced Bread Loaf Portuguese Corn Bread Pumpernickel Bread Bagel Grissini, 125 gr Olives, Saffron and Dried Fruits Bread Papari, 2 pieces Indian Cuisine Tandori Roti, 2 pieces Indian Cuisine Tandori Naan, 2 pieces Indian Cuisine Paneer Naan, 2 pieces Indian Cuisine Garlic Naan, 2 pieces Indian Cuisine 1/29 PASTRIES QTY Selection of Mini Portuguese Pastries, per piece Selection of Large Portuguese Pastries, per piece Mini Croissant Large Croissant Muffin Breakfast Cake CONDIMENTS QTY Butter pad, 10gr Butter, 20gr Butter Rosette, 30gr Butter Herbs, 20gr Traditional Portuguese Jam, 30gr Honey jar, 30gr Ketchup, small jar Mayonaise, small jar Mustard, small jar YOGHURTS QTY Organic Fruit Yoghurt, 150gr CEREALS QTY Cereal, 100gr Assorted Breakfast Cereal, mini box 250gr Assorted Breakfast Cereal, large box 400gr MUESLI & FRUITS QTY Fruit Salad, 100gr 2/29 COLD CUTS QTY Breakfast Cheeses, 300 gr Breakfast Meats, 300 gr BLINIS & PANCAKES QTY Pancakes, 2 pieces HOT BREAKFAST QTY Fried Eggs, per piece Scrambled Eggs, 2 eggs Scrambled Eggs with Baby Green Asparagus Tips, 200gr Grilled Tomatoes, 2 pieces Mushrooms, 100gr Baked Beans, 100gr -

Print Nutriton Draft

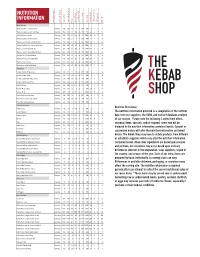

) l ) a e y g c r t ( i ) k u t ( r g s ) ( n e ) a ) g a ) b at ( g d e i g u i ( g F ) F ( s c Q M l m ( e a ) A y s m at e e r r NUTRITION c l g F o z z at y ) a i i r k o r ta m ( f g d r tt S S ( d ( e e e a i ug s s y t F n D S e e ) h s m at i i i ng ng r o g i i s e l l r r u e ( i l v v t b u n o o d r r l l o r ta ta t INFORMATION o a e e at o r a a h a r o o a S S C C F S T C S C T T P Wraps & Boxes The Box, Greens, Carved Chicken 1 Serving 380 180 20 6 0 195 690 11 4 6 38 The Box, Greens, Carved Lamb Beef 1 Serving 500 330 37 13 0 85 920 20 3 7 22 The Box, Greens, Falafel 1 Serving 460 190 22 3.5 0 10 1000 48 14 7 21 The Box, Greens, Grilled Chicken 1 Serving 470 280 31 7 0 185 780 11 3 6 36 The Box, Saffron Rice, Carved Chicken 1 Serving 720 280 31 12 0 200 1450 65 3 5 43 The Box, Saffron Rice, Carved Lamb Beef 1 Serving 840 430 48 20 0 90 1680 75 2 7 27 The Box, Saffron Rice, Falafel 1 Serving 810 290 33 10 0 15 1760 102 13 6 25 The Box, Saffron Rice, Grilled Chicken 1 Serving 810 380 42 14 0 190 1540 65 3 6 41 The Box, Fries, Carved Chicken 1 Serving 1020 470 53 8 0 195 1830 91 7 4 44 The Box, Fries, Carved Lamb Beef 1 Serving 1140 620 69 16 0 85 2060 100 6 6 28 The Box, Fries, Falafel 1 Serving 1100 490 54 6 0 10 2140 128 17 6 26 The Box, Fries, Grilled Chicken 1 Serving 1100 570 63 10 0 185 1920 91 7 5 42 The Kebabs Carved Chicken, Wrap or Box 1 Serving 260 100 12 3 0 185 610 2 1 0 34 Carved Chicken, Plate 1 Serving 360 150 16 4.5 0 255 860 2 1 0 48 Carved Lamb & Beef, Wrap or Box 1 Serving 370 250 28 11 0 75 840 11 0 -

Order Online

WRAPS & SANDWICHES DESSERTS All wraps/sandwiches are served with pita bread, $ lettuce, tomato, onion and tahini sauce. Kurdish Baklava (2 pieces) | 5.50 Ask for Gluten Free, Vegan and Vegetarian options. Layers of filo dough and pistachios in our home-made syrup Kazandibi (gf) | $5.50 Lamb & Beef Gyros Wrap | $10.95 Milk Pudding baked and caramelized Slow cooked, thin-sliced, marinated lamb & beef Kunefe | $7.50 Chicken Gyros Wrap | $10.95 Sweet shredded filo dough stuffed with salt-less cheese and A family owned and operated business Slow cooked, thin-sliced, pistachios serving delicious authentic flavors from the marinated chicken ORDER Rice Pudding (gf) | $5.00 ORDER Rice, milk, organic sugar, vanilla bean and cinnamon Mediterranean Coast to the Middle East. $ Adana Kebab Wrap | 10.95 ONLINE Decadent Chocolate Cake $7.00 Skewered charcoal grilled minced ONLINE-@ | sfkebab.--------@-------- New York Cheese Cake $7.00 Take Out, Catering lamb with fresh parsley, red onion com | and a touch of hot chili sfkebab.com Ice Cream | $5.50 ORDERORDER & Banquet Room available. Call (415) 255-2262 for Kofta Wrap | $10.95 ONLINEONLINE-@ -------- Minced beef with parsley and sumac onion WEEKEND BRUNCH -@com information. Served until 3PM sfkebab.------- Monday – Friday Salmon Wrap | $12.95 All egg dishes (except Breakfast Wrap) served with rosemary sfkebab.com Skewered charcoal grilled salmon with fresh tomato, roasted red potatoes, fresh fruit and home-made bread 11:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. lettuce and onion Mellemen (veg/gf) | $13.95 SF Kebab Mediterranean -

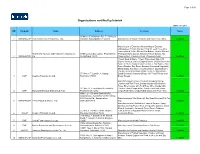

Organizations Certified by Intertek

Page 1 of 39 Organizations certified by Intertek update 30-6-2016 NO Program Name Address Certscope Status 45 Moo 1, Petchkasem Rd., T. Yaicha, A. 1 GMP&HACCP Thai Watana Rice Product Co., Ltd. Sampran Nakornpathom Thailand Manufacture of Noodle Products and Frozen Rice Stick. Certified Manufacture of Essential Oils and Natural Extracts. (Mangosteen Extract, Sompoi Extract, Leech Lime Juice Concentrated, Coffee Extract, Koi Extract, Licorice Extract, Thai-China Flavours and Fragrances Industry Co., 99 Moo 2, Lat Bua Luang, Phra Nakhon Thongpanchang Extract, Chrysanthemum Extract, Nut 2 GMP&HACCP Ltd. Si Ayutthaya 13230 Grass Extract, Pueraria Extract, Ginseng Extract) Certified Frozen Soup & Sauce, Frozen Pasteurized Egg, Chili Sauce, Ketchup, Various Dipping Sauce, Oyster Sauce and Sauce in Hermetically Sealed Container, Fish Sauce, Fish Sauce Powder, Soy Sauce Powder, Processed Vegetable, Mixed Salad, Soy Sauce, Cooking Sauce, Dipping Sauce, Vinegar & Vinegar Drinks, Salad Cream & Mayonnaise, 55 Moo. 6 T. Lumdin, A. Muang, Salad Dressing, Seasoning Paste, Oil Food Release and 3 GMP Kewpie (Thailand) Co.,Ltd. Ratchaburi 70000 Bread Spread. Certified Manufacturing of Cracker Products including Shrimp Cracker with Pork Floss, Shrimp Cracker with Chicken Floss, Rice Cracker with Pork Floss, Rice Cracker with 21 Moo 17, T.Lumlukka, A.Lumlukka, Chicken Floss, Propped Rice Cracker with Pork Floss, 4 GMP Marut and Khanom Siriphan Ltd.,Part. Phathumthani 12150 Crispy Pork Floss, Crispy Rolled Biscuit with Pork Floss Certified Office : 2/11 Bhisarn Suntornkij Rd., Sawankaloke, Sukhothai 64110 Factory: 61/4 Phichai Rd., Sawankaloke, Manufacturing of Soy Bean Oil, Soy Bean Meal and Full Fat 5 GMP&HACCP P.A.S. -

The Food Timeline

Culinary History Timeline is a listing of the culinary history timeline with article and/or information resources. http://www.foodtimeline.org/food1.html http://food.oregonstate.edu/ref/culture/ CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL ASPECTS OF FOODS (zu jedem Stichwort- entweder link / oder – Text) http://www.foodtimeline.org/foodfaqa.html Ever wonder what the Vikings ate when they set off to explore the new world? How Thomas Jefferson made his ice cream? What the pioneers cooked along the Oregon Trail? Who invented the potato chip...and why? Welcome to the Food Timeline. Food history is full of fascinating lore and contradictory facts. Historians will tell you it is not possible to express this topic in exact timeline format. They are quite right. Everything we eat is the product of culinary evolution. On the other hand? It is possible to place both foods and recipes on a timeline based on print evidence and historic context. This is what we're all about. About culinary research. P:\Frei_OltersdorfU\eTexte\Ernährungsverhalten - Daten\Ernährungsgeschichte\The food time line.doc American culinary traditions & historic surveys ---Americans at the Table: Reflections on Food and Culture, U.S. Dept. Of State ---Eating in the 20th Century, U.S.Dept. of Agriculture ---Historic American Christmas Dinner Menus ---Historic American Thanksgiving Dinner Menus ---Key Ingredients: America By Food, Smithsonian Insitution ---Not by Bread Alone: America's Culinary Heritage, Cornell Universty ---America the Bountiful, University of California at Davis ---An American Feast: Food, Dining and Entertainment in the United States (1776-1931) ---Cultural Diversity: Eating in America, Ohio State University ---Picnics in America ---School lunches ---State foods, need to cook something up for a school report? Military rations ---U.S. -

Organizations Certified by Intertek การผลิตผลิตภัณฑ์อาหารและเครื่อ

Page 1 of 40 Organizations certified by Intertek การผลติ ผลติ ภณั ฑอ์ าหารและเครอื่ งดมื่ (ISIC Code 15) update 21-04-2020 Certification NO TC Program Name Address Issue date Expiry date Status Scope number 1 83 HACCP&GMP Thai-China Flavours and Fragrances Industry Co., 99 Moo 2, Lat Bua Luang, Phra Nakhon Si Manufacture of Essential Oils and Natural Extracts. 24041107012 7th September 2018 8th September 2020 Certified (Codex) Ltd. Ayutthaya 13230 (Mangosteen Extract, Sompoi Extract, Leech Lime Juice Concentrated, Coffee Extract, Koi Extract, Licorice Extract, Thongpanchang Extract, Chrysanthemum Extract, Nut Grass Extract, Pueraria Extract, Ginseng Extract) 2 88 HACCP&GMP N.E. Agro Industry Company Limited 249 Moo 2, Ban Tanong Thown, T.Viengcom, Manufacture of Brown Sugar. 24041812004 25th March 2019 24th March 2022 Certified (Codex) A.Kumphawapi, Udonthani Province 41110 Thailand 3 113 HACCP&GMP OSC Siam Silica Co., Ltd. 6I-3A Road, Maptaphut Industrial Estate, T. MANUFACTURE OF SILICON DIOXIDE. 24040911002 11th July 2018 31st August 2021 Certified (Codex) Maptaphut, A. Muang, Rayong 21150 Thailand 4 205 HACCP&GMP P.A.S. Export & Silo Co., Ltd. Office : 2/11 Bhisarn Suntornkij Rd., Sawankaloke, MANUFACTURING OF SOY BEAN OIL. 24041411002 6th August 2017 10th August 2020 Certified (Codex) Sukhothai 64110Factory: 61/4 Phichai Rd., Sawankaloke, Sukhothai 64110 5 319 HACCP&GMP Bangkok Lab & Cosmetic Co., ltd. 48/1 Nongshaesao Road, Moo 5, Tumbon Namphu, MANUFACTURE OF DIETARY SUPPLEMENT PRODUCTS 24061502004 9th September 2019 8th September 2022 Certified (Codex) Ampur Meung, Ratchaburi 70000 Thailand (POWDER : CALCIUM, COLLAGEN AND FIBER/ TABLET : CALCIUM AND COLLAGEN/ CAPSULE : CHITOSAN) 6 510 HACCP&GMP Sahachol Food Supplies Co., Ltd. -

Divine Flavored Catering (New York) Catering Menu

Divine Flavored Catering (New York) Catering Menu Catering Menu Delivery throughout 5 boroughs plus New Rochelle & Yonkers. Delivery fees range from $35 to $100. Areas outside of this please call for delivery fee. We are now accepting Bank Transfers, Zelle, Venmo & Cashapp. Delivery Orders Must Be Picked Up Outside of The Address Given. Due to Parking Limitations We Cannot Bring Food Inside The Delivery Address. Delivery Disclosure. Mid-Manhattan to lower Manhattan $35 & higher, depending on order size. Orders above $500 a 15% delivery fee will be added to customers card at time of billing. SHIPPING NOW AVAILABLE ANYWHERE IN THE CONTINENTAL US. SHIPPING CHARGES ARE BASED ON WEIGHT AND WILL BE ADDED TO THE FINAL BILL BY THE RESTAURANT. Available: 9 am to 8 pm 7 days Order Online SHIPPING NOW AVAILABLE! WE NOW OFFER SHIPPING ANYWHERE IN THE CONTINENTAL US. SHIPPING CHARGES WILL BE BASED ON WEIGHT AND CHARGES WILL BE ADDED TO THE FINAL BILL BY THE RESTAURANT. --------------------------------------------------------- DELIVERY Delivery Orders Must Be Picked Up Outside of The Address Given. Due to Parking Limitations We Cannot Bring Food Inside The Delivery Address. ------------------------------------------------------- All Items Are Served AS IS No Modifications Allowed ------------------------------------------------------- Thanksgiving Menu ● Thanksgiving Menu 1 (Serves 10) $400 Choose 1 Appetizer; - Spiced jumbo prawns or Cream of chicken soup with French bread. 1 Salad; - Green garden salad or Baked potatoes salad. Entree; - Broiled stewed goat meat & Chicken ala orange. 1 Side; - Vegetable fried rice or Jollof rice. 1 Dessert; Fresh fruit salad or Chocolate cake. ● Thanksgiving Menu 2 (Serves 10) $400 Choice of 1 Appetizers; Meat pie / Suya (Thin sliced beef marinated in northern yajji pepper spice), or Purf purf / akara (Honey bean puree, chopped red onions, and chili with shrimp powder).