Seeking Stability at Sustainable Cost: Principles for a New U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 'New Middle East,' Revised Edition

9/29/2014 Diplomatist BILATERAL NEWS: India and Brazil sign 3 agreements during Prime Minister's visit to Brazil CONTENTS PRINT VERSION SPECIAL REPORTS SUPPLEMENTS OUR PATRONS MEDIA SCRAPBOOK Home / September 2014 The ‘New Middle East,’ Revised Edition GLOBAL CENTRE STAGE In July 2014, President Obama sent the White House’s Coordinator for the Middle East, Philip Gordon, to address the ‘Israel Conference on Peace’ in Tel-Aviv. ‘How’ Gordon asked ‘will [Israel] have peace if it is unwilling to delineate a border, end the occupation and allow for Palestinian sovereignty, security, and dignity?’ This is a good question, but Dr Emmanuel Navon asks how Israel will achieve peace if it is willing to delineate a border, end the occupation and allow for Palestinian sovereignty, security, and dignity, especially when experience, logic and deduction suggest that the West Bank would turn into a larger and more lethal version of the Gaza Strip after the Israeli withdrawal During the last war between Israel and Hamas (which officially ended with a ceasefire on August 27, 2014), US Secretary of State John Kerry inadvertently created a common ground among rivals: Israel, the Palestinian Authority, Egypt and Jordan all agreed in July 2014 that Kerry had ruined the chances of a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas. Collaborating with Turkey DEFINITION and Qatar to reach a ceasefire was tantamount to calling the neighbourhood’s pyromaniac instead of the fire department to extinguish the fire. Qatar bankrolls Hamas and Turkey advocates on its behalf. While in Paris in July, Kerry was all smiles Diplomat + with Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu whose boss, Recep Erdogan, recently accused Israel of genocide and compared Netanyahu to Hitler. -

O'hanlon Gordon Indyk

Getting Serious About Iraq 1 Getting Serious About Iraq ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Philip H. Gordon, Martin Indyk and Michael E. O’Hanlon In his 29 January 2002 State of the Union address, US President George W. Bush put the world on notice that the United States would ‘not stand aside as the world’s most dangerous regimes develop the world’s most dangerous weapons’.1 Such statements, repeated since then in various forms by the president and some of his top advisers, have rightly been interpreted as a sign of the administration’s determination to overthrow Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein.2 Since the January declaration, however, attempts by the administration to put together a precise plan for Saddam’s overthrow have revealed what experience from previous administrations should have made obvious from the outset: overthrowing Saddam is easier said than done. Bush’s desire to get rid of the Iraqi dictator has so far been frustrated by the inherent difficulties of overthrowing an entrenched regime as well as a series of practical hurdles that conviction alone cannot overcome. The latter include the difficulties of organising the Iraqi opposition, resistance from Arab and European allies, joint chiefs’ concerns about the problems of over-stretched armed forces and intelligence assets and the complications caused by an upsurge in Israeli– Palestinian violence. Certainly, the United States has good reasons to want to get rid of Saddam Hussein. Saddam is a menace who has ordered the invasion of several of his neighbours, killed thousands of Kurds and Iranians with poison gas, turned his own country into a brutal police state and demonstrated an insatiable appetite for weapons of mass destruction. -

America's Anxious Allies: Trip Report from Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel by Meghan O'sullivan, Philip Gordon, Dennis Ross, James Jeffrey

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2696 America's Anxious Allies: Trip Report from Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel by Meghan O'Sullivan, Philip Gordon, Dennis Ross, James Jeffrey Sep 28, 2016 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Meghan O'Sullivan Meghan O'Sullivan is the Jeane Kirkpatrick Professor of the Practice of International Affairs at Harvard University's Kennedy School. Philip Gordon Philip Gordon is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a former White House coordinator for the Middle East, North Africa, and the Gulf region. Dennis Ross Dennis Ross, a former special assistant to President Barack Obama, is the counselor and William Davidson Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute. James Jeffrey Ambassador is a former U.S. special representative for Syria engagement and former U.S. ambassador to Turkey and Iraq; from 2013-2018 he was the Philip Solondz Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute. He currently chairs the Wilson Center’s Middle East Program. Brief Analysis A bipartisan team of distinguished former officials share their insights from a recent tour of key regional capitals. On September 26, The Washington Institute held a Policy Forum with Meghan O'Sullivan, Philip Gordon, Dennis Ross, and James Jeffrey, who recently returned from a bipartisan tour of Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel. O'Sullivan is the Jeane Kirkpatrick Professor at Harvard's Kennedy School and former special assistant to the president for Iraq and Afghanistan. Gordon is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and former White House coordinator for the Middle East, North Africa, and the Gulf region. -

The US Perspective on NATO Under Trump: Lessons of the Past and Prospects for the Future

The US perspective on NATO under Trump: lessons of the past and prospects for the future JOYCE P. KAUFMAN Setting the stage With a new and unpredictable administration taking the reins of power in Wash- ington, the United States’ future relationship with its European allies is unclear. The European allies are understandably concerned about what the change in the presidency will mean for the US relationship with NATO and the security guar- antees that have been in place for almost 70 years. These concerns are not without foundation, given some of the statements Trump made about NATO during the presidential campaign—and his description of NATO on 15 January 2017, just days before his inauguration, as ‘obsolete’. That comment, made in a joint interview with The Times of London and the German newspaper Bild, further exacerbated tensions between the United States and its closest European allies, although Trump did claim that the alliance is ‘very important to me’.1 The claim that it is obsolete rested on Trump’s incorrect assumption that the alliance has not been engaged in the fight against terrorism, a position belied by NATO’s support of the US conflict in Afghanistan. Among the most striking observations about Trump’s statements on NATO is that they are contradicted by comments made in confirmation hear- ings before the Senate by General James N. Mattis (retired), recently confirmed as Secretary of Defense, who described the alliance as ‘essential for Americans’ secu- rity’, and by Rex Tillerson, now the Secretary of State.2 It is important to note that the concerns about the future relationships between the United States and its NATO allies are not confined to European governments and policy analysts. -

The Kosovo Report

THE KOSOVO REPORT CONFLICT v INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE v LESSONS LEARNED v THE INDEPENDENT INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON KOSOVO 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford Executive Summary • 1 It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, Address by former President Nelson Mandela • 14 and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Map of Kosovo • 18 Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Introduction • 19 Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw PART I: WHAT HAPPENED? with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Preface • 29 Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the uk and in certain other countries 1. The Origins of the Kosovo Crisis • 33 Published in the United States 2. Internal Armed Conflict: February 1998–March 1999 •67 by Oxford University Press Inc., New York 3. International War Supervenes: March 1999–June 1999 • 85 © Oxford University Press 2000 4. Kosovo under United Nations Rule • 99 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) PART II: ANALYSIS First published 2000 5. The Diplomatic Dimension • 131 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, 6. International Law and Humanitarian Intervention • 163 without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, 7. Humanitarian Organizations and the Role of Media • 201 or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. -

Inside... Exchanging Ideas on Europe the Cinema of the EU

Exchanging Ideas on Europe NEWS UACES Issue 72 Summer 2012 UACES COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH NETWORKS Read about the latest UACES CRN events. PAGES 6-7 UACES ELECTION RESULTS Meet the new UACES committee members. PAGE 12 REPORTING EUROPE PRIZE Find out who was awarded this year’s prize at the award ceremony in London. PAGE 14 European Crisis, European Solidarity Tim Haughton reports on the 2012 JCMS Annual Review lecture by Erik Jones (pictured). PAGE 5 ASK ARCHIMEDES Can Europe maximise its potential by The Cinema of the EU: European Identity harnessing the value of its knowledge and Universality economy? PAGE 15 Brussels, 10 May 2012 Mariana Liz, King’s College London Aiming to offer an institutional perspective on contemporary European cinema, this presentation, part of the UACES Arena Seminar series, was centred on the EU’s major initiative in support of the audiovisual sector, the MEDIA Programme. The event provided a timely discussion on European fi lm and identity as ‘Creative Europe’, a new programme for the cultural sector, is being fi nalised and identifi cation with the European integration project weakens in the face of an economic and political crisis. UACES Annual Running since 1991, MEDIA supports a series of initiatives in the pre- and post- General Meeting production of fi lms, with the largest share of its budget (currently at €755 million) being allocated to distribution. Although the impact of MEDIA was briefl y addressed, the 17:00 - 17:45 seminar’s main focus was on the programme’s communication. After an overview of the Sunday 2nd September history of European identity in the EU – from the Declaration signed in 1973 to the failed constitution and the signing of the Lisbon Treaty in 2007 – the presentation analysed fi ve Passau, Germany clips produced by the European Commission to promote MEDIA. -

The Media and UN "Peacekeeping"Since the Gulf War

Vol. XVII No. 1, Spring 1997 The Media and UN "Peacekeeping"Since the Gulf War by Stephen Badsey Stephen Badsey is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of War Studies at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, and a Senior Research Fellow of the Institute for the Study of War and Society at DeMontfort University. INTRODUCTION 1 The changes in United Nations (UN) "peacekeeping" operations within the last five years have been both dramatic and multifaceted. This article attempts to show that the media (particularly those of the United States, which are dominant within, and may under most circumstances be taken as virtually identical to, the international media) have in all their aspects become, and remain, critical elements in determining the success or failure of these operations. It points to three principal areas of current practice regarding the media which have contributed to the failure or partial failure of recent UN "peacekeeping" missions. One of these is a failure of understanding of the media exhibited by the government and military forces of the United States, as the result of doctrine established before the end of the Cold War. Another is the failure of the UN or its constituent members to respond effectively to anti-peacekeeper propaganda, especially that promulgated by political authorities in target countries for "peacekeeping," and including their ability to exploit the international media for propaganda purposes. The third is the failure of the UN to develop "peacekeeping" doctrine which takes the value of the media into account. The article calls for advances in international relations theory in this field as an aid to further understanding. -

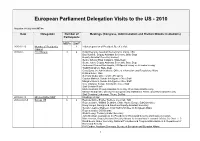

The Information Below Is Based on the Information Supplied to EPLO and Stored in Its Archives and May Differ from the Fina

European Parliament Delegation Visits to the US - 2010 Situation: 01 July 2010 MT/mt Date Delegation Number of Meetings (Congress, Administration and Bretton-Woods Institutions) Participants MEPs Staff* 2010-02-16 Member of President's 1 Initial preparation of President Buzek´s Visit Cabinet 2010-02- ECR Bureau 9 4 David Heyman, Assistant Secretary for Policy, TSA Dan Russell, Deputy Assistant Secretary ,State Dept Deputy Assistant Secretary Limbert, Senior Advisor Elisa Catalano, State Dept Stuart Jones, Deputy Assistant Secretary, State Dept Ambassor Richard Morningstar, US Special Envoy on Eurasian Energy Todd Holmstrom, State Dept Cass Sunstein, Administrator, Office of Information and Regulatory Affiars Kristina Kvien, NSC Sumona Guha, Office of Vice-President Gordon Matlock, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Margaret Evans, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Clee Johnson, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Staff Senator Risch Mark Koumans, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Dept Homeland Security Michael Scardeville, Director for European and Multilateral Affairs, Dept Homeland Security Staff Senators Lieberman, Thune, DeMint 2010-02-18 Mrs Lochbihler MEP 1 Meetings on Iran 2010-03-03-5 Bureau US 6 2 Representative Shelley Berkley, Co-Chair, TLD Representative William Delahunt, Chair, House Europe SubCommittee Doug Hengel, Energy and Sanctions Deputy Assistant Secretary Senator Jeanne Shaheen, Chair Subcommittee on European Affairs Representative Cliff Stearns Stuart Levey, Treasury Under Secretary John Brennan, Assistant to the President for -

FALL COMMENCEMENT 2020 CELEBRATING the GRADUATING CLASS So Enter That Daily Thou Mayest Grow in Knowledge Wisdom and Love

FALL COMMENCEMENT 2020 CELEBRATING THE GRADUATING CLASS So enter that daily thou mayest grow in knowledge wisdom and love. To the Class of 2020, Congratulations on your graduation from Ohio University! You are one of the fortunate who has experienced the nation’s best transformative learning experience. This year has not been what any of us had planned, as the COVID-19 global pandemic changed all of our lives. I want to thank you for boldly responding to these historic changes by continuing to learn together, work together and support one another. You have shown great resilience as you navigated the many challenges of 2020 and I am very proud of you. Your class is truly special and will always be remembered at Ohio University for your spirit and fortitude. Your time at Ohio University prepared you for your future, and now you and your classmates are beginning your careers, advancing in new academic programs or taking on other challenges. I want you to know, though, that your transformation is not yet complete. For a true education does not stop with a diploma; it continues throughout every day of your life. I encourage you to take the lessons you have learned at Ohio University and expand upon them in the years to come. As you have already learned, the OHIO alumni network is a vast enterprise – accomplished in their respectable professions, loyal to their alma mater, and always willing to help a fellow Bobcat land that next job or find an apartment/realtor in a new city. I urge you to seek out your nearest alumni chapter or a special interest society of alumni and friends, to reach out through social media (#ohioalumni), and to stay connected to Ohio University. -

Putting Europe First 71

Putting Europe First 71 Putting Europe First ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Ivo H. Daalder and James M. Goldgeier The Bush administration enters office at a time when flash-points around the globe – from the Middle East to Colombia and from the Persian Gulf to the Taiwan Straits – threaten to explode. This contrasts starkly with a Europe that today is relatively quiescent. The violence that bloodied south-eastern Europe throughout much of the 1990s has ended. Slobodan Milosevic, the man most responsible for Europe’s recent instability, has been swept from office. Except for isolated pockets like Belarus, democracy is ascendant throughout the continent. America’s oldest friends are creating an ever-closer union amongst themselves based on a single currency and a common defence and security policy. And Russia, though still struggling to emerge from decades of disastrous economic and political mismanagement, no longer threatens Europe’s stability and security. As Europe remains quiet and increasingly capable of taking care of itself, the new administration in Washington may be tempted to concentrate American efforts elsewhere around the globe. Bush’s national security adviser, Condoleezza Rice, suggested as much towards the end of last year’s presidential campaign. She said that Bush favoured a ‘new division of labour’ that would leave extended peacekeeping missions in Europe, such as those in the Balkans, to the Europeans so that the United States could focus its energies elsewhere. ‘The United States is the only power that -

The Honorable John F. Kelly January 30, 2017 Secretary Department of Homeland Security 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036

The Honorable John F. Kelly January 30, 2017 Secretary Department of Homeland Security 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 The Honorable Sally Yates Acting Attorney General Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530 The Honorable Thomas A. Shannon Acting Secretary Department of State 2201 C Street, NW Washington, DC 20520 Secretary Kelly, Acting Attorney General Yates, Acting Secretary Shannon: As former cabinet Secretaries, senior government officials, diplomats, military service members and intelligence community professionals who have served in the Bush and Obama administrations, we, the undersigned, have worked for many years to make America strong and our homeland secure. Therefore, we are writing to you to express our deep concern with President Trump’s recent Executive Order directed at the immigration system, refugees and visitors to this country. This Order not only jeopardizes tens of thousands of lives, it has caused a crisis right here in America and will do long-term damage to our national security. In the middle of the night, just as we were beginning our nation’s commemoration of the Holocaust, dozens of refugees onboard flights to the United States and thousands of visitors were swept up in an Order of unprecedented scope, apparently with little to no oversight or input from national security professionals. Individuals, who have passed through multiple rounds of robust security vetting, including just before their departure, were detained, some reportedly without access to lawyers, right here in U.S. airports. They include not only women and children whose lives have been upended by actual radical terrorists, but brave individuals who put their own lives on the line and worked side-by-side with our men and women in uniform in Iraq now fighting against ISIL. -

50-1 08 Forum.Indd

Forum Debating Bush’s Wars Editor’s note In the winter 2007–08 issue of Survival, Brookings Institution scholar Philip Gordon argued that America’s strategy against terror is failing ‘because the Bush administra- tion chose to wage the wrong war’. The Bush record is six years of failure, according to Gordon, because of a misdiagnosis of the origins of the problem, too much faith in mili- tary force and belligerent rhetoric, alienating friends and allies, conflating America’s foes into a single ‘enemy’, and misunderstanding the ideological fundamentals of the struggle. As the campaign to replace Bush intensifies, Survival invited former Bush speechwriter and Deputy Assistant to the President Peter Wehner and Kishore Mahbubani, Dean and Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore, to reflect on Gordon’s arguments. Their comments, and Philip Gordon’s response, follow. A Triumph of Ideology over Evidence Peter Wehner Philip H. Gordon is an intelligent man and a fine scholar. And ‘Winning the Right War’ makes some valid arguments (for example, highlighting the ‘resource gap’ between the rhetoric of the war against militant Islam and the resources devoted to it). But in the main I found his essay to be flawed, simplistic, and in some places even sloppy. Some of Gordon’s criticisms of the Bush administration are legitimate – I have written and spoken about those failures, especially related to Iraq, else- where – but he undermines them by presenting what is essentially a one-sided Peter Wehner, former Deputy Assistant to the President, served in the Bush administration from 2001–07.