50-1 08 Forum.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 'New Middle East,' Revised Edition

9/29/2014 Diplomatist BILATERAL NEWS: India and Brazil sign 3 agreements during Prime Minister's visit to Brazil CONTENTS PRINT VERSION SPECIAL REPORTS SUPPLEMENTS OUR PATRONS MEDIA SCRAPBOOK Home / September 2014 The ‘New Middle East,’ Revised Edition GLOBAL CENTRE STAGE In July 2014, President Obama sent the White House’s Coordinator for the Middle East, Philip Gordon, to address the ‘Israel Conference on Peace’ in Tel-Aviv. ‘How’ Gordon asked ‘will [Israel] have peace if it is unwilling to delineate a border, end the occupation and allow for Palestinian sovereignty, security, and dignity?’ This is a good question, but Dr Emmanuel Navon asks how Israel will achieve peace if it is willing to delineate a border, end the occupation and allow for Palestinian sovereignty, security, and dignity, especially when experience, logic and deduction suggest that the West Bank would turn into a larger and more lethal version of the Gaza Strip after the Israeli withdrawal During the last war between Israel and Hamas (which officially ended with a ceasefire on August 27, 2014), US Secretary of State John Kerry inadvertently created a common ground among rivals: Israel, the Palestinian Authority, Egypt and Jordan all agreed in July 2014 that Kerry had ruined the chances of a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas. Collaborating with Turkey DEFINITION and Qatar to reach a ceasefire was tantamount to calling the neighbourhood’s pyromaniac instead of the fire department to extinguish the fire. Qatar bankrolls Hamas and Turkey advocates on its behalf. While in Paris in July, Kerry was all smiles Diplomat + with Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu whose boss, Recep Erdogan, recently accused Israel of genocide and compared Netanyahu to Hitler. -

O'hanlon Gordon Indyk

Getting Serious About Iraq 1 Getting Serious About Iraq ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Philip H. Gordon, Martin Indyk and Michael E. O’Hanlon In his 29 January 2002 State of the Union address, US President George W. Bush put the world on notice that the United States would ‘not stand aside as the world’s most dangerous regimes develop the world’s most dangerous weapons’.1 Such statements, repeated since then in various forms by the president and some of his top advisers, have rightly been interpreted as a sign of the administration’s determination to overthrow Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein.2 Since the January declaration, however, attempts by the administration to put together a precise plan for Saddam’s overthrow have revealed what experience from previous administrations should have made obvious from the outset: overthrowing Saddam is easier said than done. Bush’s desire to get rid of the Iraqi dictator has so far been frustrated by the inherent difficulties of overthrowing an entrenched regime as well as a series of practical hurdles that conviction alone cannot overcome. The latter include the difficulties of organising the Iraqi opposition, resistance from Arab and European allies, joint chiefs’ concerns about the problems of over-stretched armed forces and intelligence assets and the complications caused by an upsurge in Israeli– Palestinian violence. Certainly, the United States has good reasons to want to get rid of Saddam Hussein. Saddam is a menace who has ordered the invasion of several of his neighbours, killed thousands of Kurds and Iranians with poison gas, turned his own country into a brutal police state and demonstrated an insatiable appetite for weapons of mass destruction. -

Download the Full Briefing

Briefing 4 May 2013 Why We – Especially the West – Need the UN Development System Kishore Mahbubani Western countries have created a UN development system that is underfunded and hamstrung by politics. As the relative power of the West declines, these countries should invest more in the UN to ensure global stability. Institutions of global governance are weak by design not default. Another constant of Western strategy has been to bypass established As Singapore’s permanent representative in New York, I encountered universal institutions for ad hoc groups like the G7 and G8 or senior members of the American establishment who lamented the multilateral organizations dominated by them like the Organization UN’s poor condition. The explanation was the domination by the for Economic Co-operation and Development and the North poor and weak states of Africa and Asia and the poor quality of Atlantic Treaty Organization. But they are not UN substitutes its bureaucrats. because they lack legitimacy. Even the G20, which is broadly representative, lacks a constitutional mandate and standing under To the best of my knowledge, no one seemed aware of a long- international law. It cannot replace the universal membership standing Western strategy, led primarily by Washington, to keep organizations of the UN family. The global convergence on norms the United Nations weak. Even during the Cold War, when Moscow and institutions to manage our global village requires inputs from and Washington disagreed on everything, both actively conspired legitimate global institutions. to keep the UN feeble: selecting pliable secretaries-general, such as Kurt Waldheim, and bullying them into dismissing or sidelining Most of our key global village councils are related to the United competent and conscientious international civil servants who Nations. -

America's Anxious Allies: Trip Report from Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel by Meghan O'sullivan, Philip Gordon, Dennis Ross, James Jeffrey

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2696 America's Anxious Allies: Trip Report from Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel by Meghan O'Sullivan, Philip Gordon, Dennis Ross, James Jeffrey Sep 28, 2016 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Meghan O'Sullivan Meghan O'Sullivan is the Jeane Kirkpatrick Professor of the Practice of International Affairs at Harvard University's Kennedy School. Philip Gordon Philip Gordon is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a former White House coordinator for the Middle East, North Africa, and the Gulf region. Dennis Ross Dennis Ross, a former special assistant to President Barack Obama, is the counselor and William Davidson Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute. James Jeffrey Ambassador is a former U.S. special representative for Syria engagement and former U.S. ambassador to Turkey and Iraq; from 2013-2018 he was the Philip Solondz Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute. He currently chairs the Wilson Center’s Middle East Program. Brief Analysis A bipartisan team of distinguished former officials share their insights from a recent tour of key regional capitals. On September 26, The Washington Institute held a Policy Forum with Meghan O'Sullivan, Philip Gordon, Dennis Ross, and James Jeffrey, who recently returned from a bipartisan tour of Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel. O'Sullivan is the Jeane Kirkpatrick Professor at Harvard's Kennedy School and former special assistant to the president for Iraq and Afghanistan. Gordon is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and former White House coordinator for the Middle East, North Africa, and the Gulf region. -

Seeking Stability at Sustainable Cost: Principles for a New U.S

Seeking Stability at Sustainable Cost: Principles for a New U.S. Strategy in the Middle East Report of the Task Force on Managing Disorder in the Middle East April 2017 Aaron Lobel Task Force Co-Chairs Founder and President, America Abroad Media Ambassador Eric Edelman Former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Mary Beth Long Former Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Jake Sullivan Affairs Former Director of Policy Planning, U.S. State Department Former National Security Advisor to the Vice President Alan Makovsky Former Senior Professional Staff Member, House Foreign Affairs Committee Task Force Members Ray Takeyh Ambassador Morton Abramowitz Former Senior Advisor on Iran, U.S. State Department Former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey General Charles Wald (ret., USAF) Henri Barkey Former Deputy Commander, U.S. European Command Director, Middle East Program, Woodrow Wilson International Center Former Commander, U.S. Central Command Air Forces Hal Brands Amberin Zaman Henry A. Kissinger Distinguished Professor of Global Affairs at the Columnist, Al-Monitor; Woodrow Wilson Center Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies Svante Cornell Staff Director, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program Blaise Misztal Director of National Security Ambassador Ryan Crocker Former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon Nicholas Danforth Senior Policy Analyst Ambassador Robert Ford Former Ambassador to Syria Jessica Michek Policy Analyst John Hannah Former Assistant for National Security Affairs to the Vice President Ambassador James Jeffrey Former Ambassador to Turkey and Iraq DISCLAIMER The findings and recommendations expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of the Bipartisan Policy Center’s founders or its board of directors. -

Hong Kong Magazine

THE WAY FORWARD Conference Summary 26-28 January 2021 China-United States Exchange Foundation 20/F, Yardley Commercial Building No.3 Connaught Road West, Sheung Wan Hong Kong Tel: (852) 2523 2083 Fax: (852) 2523 6116 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cusef.org.hk China Center for International Economic Exchanges No.5, Yong Ding Men Nei Street, Xicheng District Beijing, China Tel: (8610) 8336 2165 Fax: (8610) 8336 2165 Email: [email protected] Website: english.cciee.org.cn ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Tung Chee-hwa Chairman of the China-United States Exchange Foundation; Vice Chairman of the 13th CPPCC National Committee of China; Former Chief Executive of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region First of all, I want to thank all the speakers who joined us in this event. Do you know that our speakers were actually spread out in nine different time zones? Our European friends dialed in at 2 am in the morning. My great appreciation to all, for your sacrifice and your contributions. Second, I want to thank all the participants for watching or listening in. I hope the discussions in the past few days have been helpful to you — in understanding the challenges and what should be done to put the Chi- na-U.S. relationship back on the road to progress. Indeed, our many speakers and panelists have pointed out what should be done. If I were to summarize the thoughts expressed in these three days, I’d say: Return to the dialogue table. Restore respect and trust. Allow competition and cooperation to coexist. Think about the developing countries and low-income people that need help. -

The US Perspective on NATO Under Trump: Lessons of the Past and Prospects for the Future

The US perspective on NATO under Trump: lessons of the past and prospects for the future JOYCE P. KAUFMAN Setting the stage With a new and unpredictable administration taking the reins of power in Wash- ington, the United States’ future relationship with its European allies is unclear. The European allies are understandably concerned about what the change in the presidency will mean for the US relationship with NATO and the security guar- antees that have been in place for almost 70 years. These concerns are not without foundation, given some of the statements Trump made about NATO during the presidential campaign—and his description of NATO on 15 January 2017, just days before his inauguration, as ‘obsolete’. That comment, made in a joint interview with The Times of London and the German newspaper Bild, further exacerbated tensions between the United States and its closest European allies, although Trump did claim that the alliance is ‘very important to me’.1 The claim that it is obsolete rested on Trump’s incorrect assumption that the alliance has not been engaged in the fight against terrorism, a position belied by NATO’s support of the US conflict in Afghanistan. Among the most striking observations about Trump’s statements on NATO is that they are contradicted by comments made in confirmation hear- ings before the Senate by General James N. Mattis (retired), recently confirmed as Secretary of Defense, who described the alliance as ‘essential for Americans’ secu- rity’, and by Rex Tillerson, now the Secretary of State.2 It is important to note that the concerns about the future relationships between the United States and its NATO allies are not confined to European governments and policy analysts. -

Asian Studies 2021

World Scientific Connecting Great Minds ASIAN STUDIES 2021 AVAILABLE IN PRINT AND DIGITAL MORE DIGITAL PRODUCTS ON WORLDSCINET HighlightsHighlights Asian Studies Catalogue 2021 page 5 page 6 page 6 page 7 Editor-in-Chief: Kym Anderson edited by Bambang Susantono, edited by Kai Hong Phua Editor-in-Chief: Mark Beeson (University of Adelaide and Australian Donghyun Park & Shu Tian (Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, (University of Western National University, Australia) (Asian Development Bank, Philippines) National University of Singapore), et al. Australia, Australia) page 9 page 14 page 14 page 14 by Tommy Koh by Cuihong Cai by Victor Fung-Shuen Sit by Sui Yao (Ambassador-at-Large, (Fudan University, China) (University of Hong Kong, (Central University of Finance Singapore) & Lay Hwee Yeo Hong Kong) and Economics, China) (European Union Centre, Singapore) page 18 page 19 page 19 page 20 by Jinghao Zhou edited by Zuraidah Ibrahim by Alfredo Toro Hardy by Yadong Luo (Hobart and William Smith & Jeffie Lam (South China (Venezuelan Scholar (University of Miami, USA) Colleges, USA) Morning Post, Hong Kong) and Diplomat) page 26 page 29 page 32 page 32 by Cheng Li by & by Gungwu Wang edited by Kerry Brown Stephan Feuchtwang (Brookings Institution, USA) (National University of (King’s College London, UK) Hans Steinmüller (London Singapore, Singapore) School of Economics, UK) About World Scientific Publishing World Scientific Publishing is a leading independent publisher of books and journals for the scholarly, research, professional and educational communities. The company publishes about 600 books annually and over 140 journals in various fields. World Scientific collaborates with prestigious organisations like the Nobel Foundation & US ASIA PACIFIC ..................................... -

ECONOMICS and FINANCE Highlightshighlights Economics and Finance Catalogue 2019

World Scientific Connecting Great Minds 2 019 ECONOMICS AND FINANCE HighlightsHighlights Economics and Finance Catalogue 2019 page 9 page 9 page 10 page 12 by Dennis L Buchanan & edited by Michel Crouhy (NATIXIS, Editor-in-chief: by Graciela Chichilnisky Mark H A Davis (Imperial College France), Dan Galai & Zvi Wiener (The Tim Josling (Stanford) (Columbia University, USA) & Peter Bal London, UK) Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel) (Millemont Institute, USA) page 15 page 17 page 17 page 19 edited by Orley Ashenfelter (Princeton), by Victor R Fuchs (Stanford) Editor-in-chief: by Ronald W Jones Olivier Gergaud (KEDGE Business Teh-wei Hu (UC Berkeley) (University of Rochester, USA) School, France), Karl Storchmann (New York University, USA) & William Ziemba (UBC & London School of Economics, UK) page 19 page 22 page 23 page 25 edited by Dieter Ernst (East-West Center, by Henry Thompson by William T Ziemba (UBC & London by Alexander Lipton, USA & The Centre for International (Auburn University, USA) School of Economics, UK), Mikhail Quant of the Year 2000 Governance Innovation/CIGI, Canada) & Zhitlukhin (The Russian Academy of (MIT Connection Science, USA) Michael G Plummer (The Johns Hopkins Sciences, Russia) & Sebastien Lleo University, SAIS, Italy) (NEOMA Business School, France) page 26 page 28 page 29 page 29 by Robert Jarrow (Cornell) & edited by Pierre Perron edited by Charles-Albert Lehalle by Richard L Sandor (American Arkadev Chatterjea (Boston University, USA) (Capital Fund Management, France Financial Exchange, USA & (Indiana University, USA) & Imperial College London, UK) & Environmental Financial Products, Sophie Laruelle (UniversitéParis-Est LLC, USA & University of Chicago Law Créteil, France) School, USA) About World Scientific Publishing World Scientific Publishing is a leading independent c o n t e n t s publisher of books and journals for the scholarly, research, professional and educational communities. -

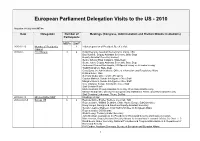

The Information Below Is Based on the Information Supplied to EPLO and Stored in Its Archives and May Differ from the Fina

European Parliament Delegation Visits to the US - 2010 Situation: 01 July 2010 MT/mt Date Delegation Number of Meetings (Congress, Administration and Bretton-Woods Institutions) Participants MEPs Staff* 2010-02-16 Member of President's 1 Initial preparation of President Buzek´s Visit Cabinet 2010-02- ECR Bureau 9 4 David Heyman, Assistant Secretary for Policy, TSA Dan Russell, Deputy Assistant Secretary ,State Dept Deputy Assistant Secretary Limbert, Senior Advisor Elisa Catalano, State Dept Stuart Jones, Deputy Assistant Secretary, State Dept Ambassor Richard Morningstar, US Special Envoy on Eurasian Energy Todd Holmstrom, State Dept Cass Sunstein, Administrator, Office of Information and Regulatory Affiars Kristina Kvien, NSC Sumona Guha, Office of Vice-President Gordon Matlock, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Margaret Evans, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Clee Johnson, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Staff Senator Risch Mark Koumans, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Dept Homeland Security Michael Scardeville, Director for European and Multilateral Affairs, Dept Homeland Security Staff Senators Lieberman, Thune, DeMint 2010-02-18 Mrs Lochbihler MEP 1 Meetings on Iran 2010-03-03-5 Bureau US 6 2 Representative Shelley Berkley, Co-Chair, TLD Representative William Delahunt, Chair, House Europe SubCommittee Doug Hengel, Energy and Sanctions Deputy Assistant Secretary Senator Jeanne Shaheen, Chair Subcommittee on European Affairs Representative Cliff Stearns Stuart Levey, Treasury Under Secretary John Brennan, Assistant to the President for -

FALL COMMENCEMENT 2020 CELEBRATING the GRADUATING CLASS So Enter That Daily Thou Mayest Grow in Knowledge Wisdom and Love

FALL COMMENCEMENT 2020 CELEBRATING THE GRADUATING CLASS So enter that daily thou mayest grow in knowledge wisdom and love. To the Class of 2020, Congratulations on your graduation from Ohio University! You are one of the fortunate who has experienced the nation’s best transformative learning experience. This year has not been what any of us had planned, as the COVID-19 global pandemic changed all of our lives. I want to thank you for boldly responding to these historic changes by continuing to learn together, work together and support one another. You have shown great resilience as you navigated the many challenges of 2020 and I am very proud of you. Your class is truly special and will always be remembered at Ohio University for your spirit and fortitude. Your time at Ohio University prepared you for your future, and now you and your classmates are beginning your careers, advancing in new academic programs or taking on other challenges. I want you to know, though, that your transformation is not yet complete. For a true education does not stop with a diploma; it continues throughout every day of your life. I encourage you to take the lessons you have learned at Ohio University and expand upon them in the years to come. As you have already learned, the OHIO alumni network is a vast enterprise – accomplished in their respectable professions, loyal to their alma mater, and always willing to help a fellow Bobcat land that next job or find an apartment/realtor in a new city. I urge you to seek out your nearest alumni chapter or a special interest society of alumni and friends, to reach out through social media (#ohioalumni), and to stay connected to Ohio University. -

Putting Europe First 71

Putting Europe First 71 Putting Europe First ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Ivo H. Daalder and James M. Goldgeier The Bush administration enters office at a time when flash-points around the globe – from the Middle East to Colombia and from the Persian Gulf to the Taiwan Straits – threaten to explode. This contrasts starkly with a Europe that today is relatively quiescent. The violence that bloodied south-eastern Europe throughout much of the 1990s has ended. Slobodan Milosevic, the man most responsible for Europe’s recent instability, has been swept from office. Except for isolated pockets like Belarus, democracy is ascendant throughout the continent. America’s oldest friends are creating an ever-closer union amongst themselves based on a single currency and a common defence and security policy. And Russia, though still struggling to emerge from decades of disastrous economic and political mismanagement, no longer threatens Europe’s stability and security. As Europe remains quiet and increasingly capable of taking care of itself, the new administration in Washington may be tempted to concentrate American efforts elsewhere around the globe. Bush’s national security adviser, Condoleezza Rice, suggested as much towards the end of last year’s presidential campaign. She said that Bush favoured a ‘new division of labour’ that would leave extended peacekeeping missions in Europe, such as those in the Balkans, to the Europeans so that the United States could focus its energies elsewhere. ‘The United States is the only power that