Media Reform and Democratization: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SERVICII DE TELEVIZIUNE Agenda

“ TELEKOM TV CEA MAI BUNA EXPERIENTA DE DIVERTISMENT” SERVICII DE TELEVIZIUNE agenda INTRO SERVICII TELEVIZIUNE IPTV ARGUMENTE DE VANZARE CONTINUT FUNCTIONALITATI DVBC ARGUMENTE DE VANZARE CONTINUT FUNCTIONALITATI DTH ARGUMENTE DE VANZARE CONTINUT FUNCTIONALITATI CATV ARGUMENTE DE VANZARE 2 TEHNOLOGIILE TV DISPONIBILE IN TELEKOM DTH =Televiziune digitala prin satelit IPTV = Televiziune digitala prin Internet DTH (Direct To Home) este intregul sistem de transmitere a IPTV (Internet Protocol Television ) reprezinta comunicarea semnalului de la HeadEnd pana la satelit si inapoi catre imaginilor si a sunetului intr-o retea care se bazează pe IP. In sistemul de receptie al abonatului. Romtelecom IPTV-ul este disponibil in retelele ADSL, VDSL si GPON. CATV = Televiziune analogica DVB-C = Televiziune digitala prin cablu CATV ( Community Access Television ) este sistemul de DVB-C (Digital Video Broadcasting - Cable) reprezinta distribuire a canalelor TV catre abonati prin intermediul standardul de emisie a televiziuniilor prin cablu in sistem semnalelor RF transmise prin cablu coaxial. digital. In Telekom, aceasta tehnologie este oferita prin intermediul retelelor FTTB/FTTH. Nu sunt necesare echipamente sublimentare pentru functionarea serviciului . Permite conectarea unui numar nelimitat de TV-uri in casa abonatului; 3 SOLUTII COMPLETE DE TELEVIZIUNE cea mai mare diversitate de canale TV cunoscute pentru majoritatea oamenilor (canale must have) competitii sportive in exclusivitate televiziune online gratuita promotii cu HBO inclus (canalul -

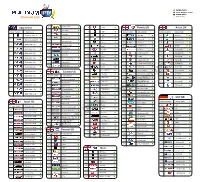

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS with SUNRISE TV TV Channel List for Printing

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS WITH SUNRISE TV TV channel list for printing Need assistance? Hotline Mon.- Fri., 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. Sat. - Sun. 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. 0800 707 707 Hotline from abroad (free with Sunrise Mobile) +41 58 777 01 01 Sunrise Shops Sunrise Shops Sunrise Communications AG Thurgauerstrasse 101B / PO box 8050 Zürich 03 | 2021 Last updated English Welcome to Sunrise TV This overview will help you find your favourite channels quickly and easily. The table of contents on page 4 of this PDF document shows you which pages of the document are relevant to you – depending on which of the Sunrise TV packages (TV start, TV comfort, and TV neo) and which additional premium packages you have subscribed to. You can click in the table of contents to go to the pages with the desired station lists – sorted by station name or alphabetically – or you can print off the pages that are relevant to you. 2 How to print off these instructions Key If you have opened this PDF document with Adobe Acrobat: Comeback TV lets you watch TV shows up to seven days after they were broadcast (30 hours with TV start). ComeBack TV also enables Go to Acrobat Reader’s symbol list and click on the menu you to restart, pause, fast forward, and rewind programmes. commands “File > Print”. If you have opened the PDF document through your HD is short for High Definition and denotes high-resolution TV and Internet browser (Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari...): video. Go to the symbol list or to the top of the window (varies by browser) and click on the print icon or the menu commands Get the new Sunrise TV app and have Sunrise TV by your side at all “File > Print” respectively. -

Mini Hd Mały Hd Duży Hd Mega Hd Mega + Hd

MINI HD MAŁY HD DUŻY HD MEGA HD MEGA + HD TVP1 HD TVP1 HD TVP1 HD TVP1 HD TVP1 HD TVP2 HD TVP2 HD TVP2 HD TVP2 HD TVP2 HD TVN HD TVN HD TVN HD TVN HD TVN HD Polsat HD Polsat HD Polsat HD Polsat HD Polsat HD TV4 TV4 TV4 TV4 TV4 TV6 TV6 TV6 TV6 TV6 TVN7 HD TVN7 HD TVN7 HD TVN7 HD TVN7 HD TTV TTV TTV TTV TTV Polsat 2 Polsat 2 BBC HD BBC HD BBC HD TVP Polonia TVP Polonia TVP HD TVP HD TVP HD TV Puls TV Puls Polsat 2 Polsat 2 Polsat 2 Puls 2 Puls 2 TVP Polonia TVP Polonia TVP Polonia Tele 5 Tele 5 TV Puls TV Puls TV Puls Polonia 1 Polonia 1 Puls 2 Puls 2 Puls 2 Mango 24 Mango 24 Tele 5 Tele 5 Tele 5 ATM Rozrywka TV ATM Rozrywka Polonia 1 Polonia 1 Polonia 1 Religia TV Edusat HD Mango 24 Mango 24 Mango 24 TV Trwam TVR HD ATM Rozrywka ATM Rozrywka ATM Rozrywka Kościół HD na żywo TVS HD Edusat HD Edusat HD Edusat HD Polsat Sport News Religia TV TVR HD TVR HD TVR HD TVP Info Szczecin TV Trwam TVS HD TVS HD TVS HD TVP Info Gorzów Kościół HD na żywo Religia TV Religia TV Religia TV TVP Info Polsat Sport News TV Trwam TV Trwam TV Trwam TVP Łódź TVN 24 HD Kościół HD na żywo Kościół HD na żywo Kościół HD na żywo TVP Wrocław Polsat News Polsat Sport News Polsat Sport News Polsat Sport News TVP Warszawa Polsat Biznes TVN 24 HD TVN 24 HD TVN 24 HD TVP Rzeszów TVN Biznes i Świat Polsat News Polsat News Polsat News TVP Olsztyn TVP Info Szczecin Polsat Biznes Polsat Biznes Polsat Biznes TVP Katowice TVP Info Gorzów TVN Biznes i Świat TVN Biznes i Świat TVN Biznes i Świat TVP Gdańsk TVP Info TVP Info Szczecin TVP Info Szczecin TVP Info Szczecin Stopklatka -

Decizia Nr. 1068 Din 21.11.2019 Privind Somarea S.C. UPC ROMÂNIA S.R.L

CONSILIUL NA Ţ IONAL AL AUDIOVIZUALULUI ROMÂNIA Autoritate publică BUCUREŞTI autonomă Bd. Libertăţii nr. 14 Tel.: 00 4 021 3055356 Sector 5, CP 050706 Fax: 00 4 021 3055354 www.cna.ro [email protected] Decizia nr. 1068 din 21.11.2019 privind somarea S.C. UPC ROMÂNIA S.R.L. Bucureşti, str. Sg. Constantin Ghercu nr. 1A, et. 8-10, sector 6 C.U.I. 12288994 Fax: 0311018101 Întrunit în şedinţă publică în ziua de 21 noiembrie 2019, Consiliul Naţional al Audiovizualului a analizat situația întocmită de Serviciul Inspecţie cu privire la reţelele de comunicaţii electronice din localitățile Ocland și Ocna de Jos, jud. Harghita și Tulcea, jud. Tulcea, aparţinând S.C. UPC ROMÂNIA S.R.L. Distribuitorul de servicii S.C. UPC ROMÂNIA S.R.L. deţine următoarele avize de retransmisie: - nr. A 5776/21.02.2008 pentru localitatea Ocland, jud. Harghita; - nr. A 5781/21.02.2008 pentru localitatea Ocna de Jos, jud. Harghita; - nr. A 5801/22.07.2019 pentru localitatea Tulcea, jud. Tulcea. În urma analizării situației sintetizate prezentate de Serviciul Inspecție, membrii Consiliului au constatat că distribuitorul de servicii S.C. UPC ROMÂNIA S.R.L. a încălcat prevederile articolelor 74 alin. (3) și 82 alin. (2) din Legea audiovizualului nr. 504/2002, cu modificările şi completările ulterioare. Potrivit dispozițiilor invocate: Art. 74 alin. (3): Distribuitorii de servicii pot modifica structura ofertei de servicii de programe retransmise numai cu acordul Consiliului. Art. 82 alin. (2): Distribuitorii care retransmit servicii de programe au obligaţia, la nivel regional şi local, să includă în oferta lor cel puţin două programe regionale şi două programe locale, acolo unde acestea există; criteriul de departajare va fi ordinea descrescătoare a audienţei. -

Liste Des Chaines

Available channel temporary unabled channel disabled channel Channels List channel replay Setanta Sport 46 92 Gold Family UK Asian UK 47 Box Nation channel number channel name 93 Dave channel number channel name channel number channel name 48 ESPN HD 1 beIN Sports News HD 94 Alibi 104 SKY ONE 158 Zee tv UK 49 Eurosport UK 95 E4 105 Sky Two UK 159 Zee cinema UK 2 Bein Sports Global HD 50 Eurosport 2 UK 96 More 4 106 Sky Living 160 Zee Punjabi UK 3 BEIN SPORT 1 HD 51 Sky Sports News 97 Dmax 107 Sky Atlantic UK 161 Zing UK 52 At The Races 4 BEIN SPORT 2 HD 98 5 STAR 108 Sky Arts1 162 Star Gold UK 53 Racing UK 5 BEIN SPORT 3 HD 99 3E 109 Sky Real Lives UK 163 Star Jalsha UK 54 Motor TV 100 Magic 110 Fox UK 164 Star Plus UK 6 BEIN SPORT 4 HD 55 Manchester United Tv 101 TV 3 111 Comedy Central UK 165 Star live UK 7 BEIN SPORT 5 HD 56 Chealsea Tv 102 Film 4 121 Comedy Central Extra UK 166 Ary Digital UK 57 Liverpool Tv 8 BEIN SPORT 6 HD 103 Flava 125 Nat Geo UK 167 Sony Tv UK 113 Food Network 126 Nat Geo Wild uk 168 Sony Sab Tv UK 9 BEIN SPORT 7 HD Cinema Uk 114 The Vault 127 Discovery UK 169 Aaj Tak UK 10 BEIN SPORT 8 HD channel number channel name 115 CBS Reality 128 Discovery Science uk 170 Geo TV UK 60 Sky Movies Premiere UK 11 BEIN SPORT 9 HD 116 CBS Action 129 Discovery Turbo UK 171 Geo news UK 61 Sky Select UK 12 BEIN SPORT 10 HD 130 Discovery History 172 ABP news Uk 62 Sky Action UK 117 CBS Drama 131 Discovery home UK 13 BEIN SPORT 11 HD 63 Sky Modern Great UK 118 True Movies 132 Investigation Discovery 64 Sky Family UK 119 True Movies -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

GOLD Package Channel & VOD List

GOLD Package Channel & VOD List: incl Entertainment & Video Club (VOD), Music Club, Sports, Adult Note: This list is accurate up to 1st Aug 2018, but each week we add more new Movies & TV Series to our Video Club, and often add additional channels, so if there’s a channel missing you really wanted, please ask as it may already have been added. Note2: This list does NOT include our PLEX Club, which you get FREE with GOLD and PLATINUM Packages. PLEX Club adds another 500+ Movies & Box Sets, and you can ‘request’ something to be added to PLEX Club, and if we can source it, your wish will be granted. ♫: Music Choice ♫: Music Choice ♫: Music Choice ALTERNATIVE ♫: Music Choice ALTERNATIVE ♫: Music Choice DANCE EDM ♫: Music Choice DANCE EDM ♫: Music Choice Dance HD ♫: Music Choice Dance HD ♫: Music Choice HIP HOP R&B ♫: Music Choice HIP HOP R&B ♫: Music Choice Hip-Hop And R&B HD ♫: Music Choice Hip-Hop And R&B HD ♫: Music Choice Hit HD ♫: Music Choice Hit HD ♫: Music Choice HIT LIST ♫: Music Choice HIT LIST ♫: Music Choice LATINO POP ♫: Music Choice LATINO POP ♫: Music Choice MC PLAY ♫: Music Choice MC PLAY ♫: Music Choice MEXICANA ♫: Music Choice MEXICANA ♫: Music Choice Pop & Country HD ♫: Music Choice Pop & Country HD ♫: Music Choice Pop Hits HD ♫: Music Choice Pop Hits HD ♫: Music Choice Pop Latino HD ♫: Music Choice Pop Latino HD ♫: Music Choice R&B SOUL ♫: Music Choice R&B SOUL ♫: Music Choice RAP ♫: Music Choice RAP ♫: Music Choice Rap 2K HD ♫: Music Choice Rap 2K HD ♫: Music Choice Rock HD ♫: Music Choice -

Chaines De La France

Chaines de la France CORONAVIRUS TF1 TF1 HEURE LOCALE -6 M6 M6 HEURE LOCALE -6 FRANCE O FRANCE 0 -6 FRANCE 1 ST-PIERRE ET MIQUELON FRANCE 2 FRANCE 2-6 FRANCE 3 FRANCE 3 HEURE LOCALE -6 FRANCE 4 FRANCE 4-6 FRANCE 5 FRANCE 5-6 BFM LCI EURONEWS TV5 CNEWS FRANCE 24 LCP PARI C8 C8 -6 W9 W9 HEURE LOCALE -6 FILM DE LA SÉRIE TF1 6TER PREMIÈRE DE PARIS 13E RUE TFX COMÉDIE PLUS DISTRICT DU CRIME SYFY FR ALTICE STUDIO POLAIRE + CANAL PARAMOUNT DÉCALE PARAMOUNT CLUB DE SÉRIE WARNER BREIZH NOVELAS NOLLYWOOD FR ÉPIQUE DE NOLLYWOOD A + TCM CINÉMA TMC TEVA HISTOIRE DE LA RCM AB1 CSTAR ACTION E! CHERIE 25 NRJ 12 OCS GEANTS OCS CHOC OCS MAX CANAL + CANAL + DECALE SÉRIE CANAL + CANEL + FAMILLE CINÉ + PREMIER CINÉ + FRISSON CINÉ + ÉMOTION CINÉ + CLASSIQUE CINÉ + FAMIZ CINÉ + CLUB ARTE USHUAIA VOYAGE GÉOGRAPHIQUE NATIONALE NATIONAL WILD CHAÎNE DE DÉCOUVERTE ID DE DÉCOUVERTE FAMILLE DE DÉCOUVERTE DÉCOUVERTE SC MUSÉE SAISONS CHASSE ET PECHE ANIMAUX PLANETE + PLANETE + CL PLANÈTE A ET E RMC DECOUVERTE TOUTE LHISTOIRE HISTOIRE MON TÉLÉVISEUR ZEN CSTAR HITS BELGIQUE PERSONNES NON STOP CLIQUE TV VICE TV RANDONNÉE RFM FR MTV DJAZZ MCM TRACE NRJ HITS MTV HITS MUSIQUE M6 Voici la liste des postes en français Québec inclus dans le forfait Diablo Liste des canaux FRENCH Québec TVA MONTRÉAL TVA MONTRÉAL WEB TVA SHERBROOKE TVA QUÉBEC TVA GATINEAU TVA TROIS RIVIERE WEB TVA HULL WEB TVA OUEST NOOVO NOOVO SHERBROOKE WEB NOOVO TROIS RIVIERE WEB RADIO CANADA MONTRÉAL ICI TELE WEB RADIO CANADA OUEST RADIO CANADA VANCOUVER RADIO CANADA SHERBROOKE RADIO CANADA QUÉBEC RADIO CANADA -

1 Consiliul Na Ț Ional Al Audiovizualului

CONSILIUL NAȚ IONAL AL AUDIOVIZUALULUI ROMÂNIA Autoritate publică autonomă BUCUREȘ TI Tel.: 00 4 021 3055356 Bd. Libertății nr. 14 Sector 5, CP 050706 Fax: 00 4 021 3055354 www.cna.ro [email protected] Decizia nr. 197/20.02.2020 privind amendarea cu 10.000 lei a S.C. RCS & RDS S.A., Str. Dr. Staicovici nr. 75, Forum 2000 Building, faza I, etaj 2, sector 5, BUCUREŞTI CUI 5888716 Fax: 0314004441 Întrunit în şedinţă publică în ziua de 20.02.2020, Consiliul Naţional al Audiovizualului a analizat raportul întocmit de Serviciul Inspecţie cu privire la reţeaua de comunicaţii electronice - staţia cap de reţea cu denumirea RCS&RDS Tulcea, aparţinând S.C. RCS&RDS SA. Distribuitorul de servicii S.C. RCS&RDS SA deţine avizul de retransmisie nr. A 7586/02.10.2012 pentru localitatea Tulcea, jud. Tulcea. Analizând raportul prezentat de Serviciul Inspecţie, membrii Consiliului au constatat că distribuitorul de servicii a încălcat prevederile art. 74 alin. (3) din Legea audiovizualului nr. 504/2002, cu modificările şi completările ulterioare, întrucât a retransmis servicii de programe fără a fi înscrise în oferta de servicii şi fără a solicita acordul Consiliului înainte de modificarea structurii acesteia. Potrivit dispoziţiilor invocate, distribuitorii de servicii pot modifica structura ofertei de servicii de programe retransmise numai cu acordul Consiliului. Potrivit raportului de constatare, în urma controlului efectuat de inspectorul teritorial al C.N.A. în data de 31.01.2020 în localitatea Tulcea, judeţul Tulcea, unde s-a efectuat un control la staţia cap de reţea cu denumirea RCS&RDS Tulcea, aparţinând S.C. -

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List Australia FOX Sport 502 FOX LEAGUE HD Australia FOX Sport 504 FOX FOOTY HD Australia 10 Bold Australia SBS HD Australia SBS Viceland Australia 7 HD Australia 7 TV Australia 7 TWO Australia 7 Flix Australia 7 MATE Australia NITV HD Australia 9 HD Australia TEN HD Australia 9Gem HD Australia 9Go HD Australia 9Life HD Australia Racing TV Australia Sky Racing 1 Australia Sky Racing 2 Australia Fetch TV Australia Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Rugby League 1 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 2 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 3 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 1HD Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 2HD Australia -

Generalistes 1. TF1 HD 2. M6 HD 3. Canal+ HD 4. Canal+ Decale

01 – FR – Generalistes 19. Serie Club HD 8. Nickelodeon Junior 1. TF1 HD 20. RTL9 9. Piwi+ HD 2. M6 HD 21. 13 Eme Rue HD 10. Nick4Teens 3. Canal+ HD 22. SyFy HD 11. Boing HD 4. Canal+ Decale HD 23. NT1 12. Canal J HD 5. France 2 HD 03 – FR – Sport 13. Boomerang HD 6. France 3 HD 1. Canal+ Sport HD 14. Manga 7. France 4 2. BEIN Sport 1 FR HD 15. GameOne 8. France 5 HD 3. BEIN Sport 2 FR HD 16. Cartoon Network HD 9. France O HD 4. BEIN Sport 3 FR HD 17. Disney Cinema 10. 6ter HD 5. SFR Sport 1 HD TEST 06 – FR – Infos - News 11. HD1 6. SFR Sport 2 HD 1. Euro News FR 12. Numero 23 HD 7. SFR Sport 3 HD 2. iTele HD 13. Cherie 25 HD 8. Foot+ 24h 3. FRANCE 24 FR 14. ARTE HD 9. GOLF+ HD 4. BFM TV 15. TV5 Monde 10. Infosport+ HD 5. LCI HD 16. W9 HD 11. Eurosport+ HD 06-1 – FR – Decalage +6 TS 17. D8 HD 12. Eurosport HD 1. TF1 HD +6 18. D17 HD 13. Eurosport 2 HD 2. M6 HD +6 19. Paris Premiere HD 14. Ma Chaine Sport HD 3. Canal+ HD +6 20. Comedie+ HD 15. OM TV HD 4. France 2 HD +6 21. E! Entertainment 16. BEIN Sport Max 5 HD 5. France 3 HD +6 22. June HD 17. BEIN Sport Max 6 HD 6. France 4 +6 23. Teva HD 18. BEIN Sport Max 7 HD 7. -

Must-Carry Rules, and Access to Free-DTT

Access to TV platforms: must-carry rules, and access to free-DTT European Audiovisual Observatory for the European Commission - DG COMM Deirdre Kevin and Agnes Schneeberger European Audiovisual Observatory December 2015 1 | Page Table of Contents Introduction and context of study 7 Executive Summary 9 1 Must-carry 14 1.1 Universal Services Directive 14 1.2 Platforms referred to in must-carry rules 16 1.3 Must-carry channels and services 19 1.4 Other content access rules 28 1.5 Issues of cost in relation to must-carry 30 2 Digital Terrestrial Television 34 2.1 DTT licensing and obstacles to access 34 2.2 Public service broadcasters MUXs 37 2.3 Must-carry rules and digital terrestrial television 37 2.4 DTT across Europe 38 2.5 Channels on Free DTT services 45 Recent legal developments 50 Country Reports 52 3 AL - ALBANIA 53 3.1 Must-carry rules 53 3.2 Other access rules 54 3.3 DTT networks and platform operators 54 3.4 Summary and conclusion 54 4 AT – AUSTRIA 55 4.1 Must-carry rules 55 4.2 Other access rules 58 4.3 Access to free DTT 59 4.4 Conclusion and summary 60 5 BA – BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 61 5.1 Must-carry rules 61 5.2 Other access rules 62 5.3 DTT development 62 5.4 Summary and conclusion 62 6 BE – BELGIUM 63 6.1 Must-carry rules 63 6.2 Other access rules 70 6.3 Access to free DTT 72 6.4 Conclusion and summary 73 7 BG – BULGARIA 75 2 | Page 7.1 Must-carry rules 75 7.2 Must offer 75 7.3 Access to free DTT 76 7.4 Summary and conclusion 76 8 CH – SWITZERLAND 77 8.1 Must-carry rules 77 8.2 Other access rules 79 8.3 Access to free DTT