The First Amendment Case for Corporate Religious Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. XX-XX In the Supreme Court of the United States KATHLEEN SEBELIUS, SECRETARY OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, ET AL., PETITIONERS v. HOBBY LOBBY STORES, INC., ET AL. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI DONALD B. VERRILLI, JR. Solicitor General Counsel of Record STUART F. DELERY Assistant Attorney General EDWIN S. KNEEDLER Deputy Solicitor General JOSEPH R. PALMORE Assistant to the Solicitor General MARK B. STERN ALISA B. KLEIN Attorneys Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 [email protected] (202) 514-2217 QUESTION PRESENTED The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA), 42 U.S.C. 2000bb et seq., provides that the government “shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion” unless that burden is the least restrictive means to further a compelling governmen- tal interest. 42 U.S.C. 2000bb-1(a) and (b). The ques- tion presented is whether RFRA allows a for-profit corporation to deny its employees the health coverage of contraceptives to which the employees are other- wise entitled by federal law, based on the religious objections of the corporation’s owners. (I) PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS Petitioners are Kathleen Sebelius, Secretary of Health and Human Services; the Department of Health and Human Services; Thomas E. Perez, Secre- tary of Labor; the Department of Labor; Jacob J. Lew, Secretary of the Treasury; and the Department of the Treasury. Respondents are Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc.; Mardel, Inc.; David Green; Barbara Green; Mart Green; Steve Green; and Darsee Lett. -

Oklahoma Department of Career and Technology Education

Oklahoma Department of Career and Technology Education Information Commons / Research August 2012 Metro Technology Center Economic Overview Report Economic Modeling Specialists, Inc. | www.economicmodeling.com Region Info Name: Metro Technology Center County Areas: Oklahoma, Oklahoma (40109) Metro Technology Center Population (2011) 730,090 Jobs (2011) 539,771 Average Earnings (2011) $50,050 Unemployed (2/2012) 20,672 Completions (2010) 12,388 GRP (2011) $41,386,855,056 Exports (2011) $72,698,600,435 Imports (2011) $45,876,219,885 Economic Modeling Specialists, Inc. | www.economicmodeling.com 1 Metro Technology Center | Population 730,090 5.7% 2011 Population Population Growth for the Last 5 Years 19.2% of State National Growth 4.7% 2011 % of Age Group Population Population Under 5 years 54,150 7.4% 5 to 9 years 50,543 6.9% 10 to 14 years 47,596 6.5% 15 to 19 years 46,300 6.3% 20 to 24 years 56,054 7.7% 25 to 29 years 59,557 8.2% 30 to 34 years 52,937 7.3% 35 to 39 years 45,764 6.3% 40 to 44 years 44,285 6.1% 45 to 49 years 47,333 6.5% 50 to 54 years 50,978 7.0% 55 to 59 years 45,747 6.3% 60 to 64 years 38,971 5.3% 65 to 69 years 27,503 3.8% 70 to 74 years 20,370 2.8% 75 to 79 years 16,659 2.3% 80 to 84 years 13,089 1.8% 85 years and over 12,253 1.7% Economic Modeling Specialists, Inc. -

1309 North Meridian Avenue Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73107 114 Multifamily Units Proximate to Major Arterials

1309 North Meridian Avenue Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73107 114 Multifamily Units Proximate to Major Arterials • Convenient drive times to retail, entertainment, and casual dining • Less than ten minutes from Southern Nazarene University and OSU-OKC • Proximate to major arterials with access to chief employers across Oklahoma City OFFER SOLICITATION PROCESS PROPERTY VISITATION Prospective purchasers will have the opportunity to visit Meridian Mansions (Property) via pre-scheduled property tours. These tours CONTACT INFORMATION will include access to a representative sampling of units and access OKLAHOMA CITY OFFICE to common areas and other similar facilities. In order to accommodate 204 North Robinson the Property’s ongoing operations, property visitation will require advance notice and scheduling. Suite 700 Oklahoma City, OK 73102 T 405-602-3040 OFFER SUBMISSION Offers should be presented in the form of a non-binding Letter of Intent, spelling out the significant terms and conditions of Purchaser’s offers including, but not limited to (1) asset pricing, (2) due diligence Justin Wilson and closing time frame, (3) Earnest Money deposit, (4) a description T 405-605-2546 of the debt / equity structure, and (5) qualifications to close. The [email protected] purchase terms shall require that all cash be paid at closing. Offers should be delivered to the attention of one of the brokers at the email addresses listed. Ted Prince T 405-630-0862 FINANCING [email protected] For parties interested in receiving debt quotes, ARA facilitates -

March Briefcase

March, 2021 Vol. 54, No. 3 A Publication of the OKLAHOMA COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION WWW.OKCBAR.ORG A Very Special “Special Judge” By Jeffery W. Massey, Asst. Dist. Atty How does one approach the sometimes sensitive sub- ject of asking a judge about his taking leave of the bench? Such decisions are deeply personal and often sensitive. However the departure of the Hon. Geary Walke was undertaken with grace and poise; just like his tenure on the bench. The Judge departed the courthouse without great fanfare or pomp. His request. Those that knew him desired to sing his accolades and years of devoted service. I had the fortune of being practicing before His Honor for two years and observed the passion and dignity he brought to his court. Now that a few months have passed, I have successfully tracked down the elusive retired jurist for observations and missives regarding his career. Oyez, Oyez, Oyez! Draw near for the Hon. Geary Walke, late special judge of the Oklahoma County District Court: On Retirement: The Frightful Coronavirus Pandemic of 2020 was a great time to retire. Forced social isolation resulted in con- stant reading, purely for enjoyment, and more relaxation/ couch potato training than anyone needs. I memorized all the dialogue for every episode of every season of The Big Bang Theory. I actually read all the articles in each National Geographic (not just perusing the photos). I am enjoying my granddaughters who are talented and probably the smartest girls in the entire world. I’m getting reacquainted with my wife, Barbara (who was my high school sweetheart and who retired from Hobby Lobby Corporate office in June), which has been a treat. -

Yukon Village Yukon Village

YUkon village newYUkon construction village suburbnew construction of oklahoma city suburb of oklahoma city CLICK HERE AND EXECUTE CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENT FOR FULL MARKETING PACKAGE one of the lowest For more info on this opportunity please contact: RICK SANNER BOB SANNER unemployment rates and [email protected] | (415) 274-2709 [email protected] | (415) 274-2717 highest growth rates in the us CA DRE #: 01792433 CA DRE #: 00869657 1600 Garth Brooks Blvd, Yukon, OK 73099 JOHN ANDREINI CHRIS KOSTANECKI [email protected] | (415) 274-2715 [email protected] | (415) 274-2701 CA BRE# 01440360 In Association with: Bob CA BRE# 01002010 Sullivan, OK Licensed Broker In Association(405) 840 0610 with rsullivan@: Bob Sullivan, OK Licensed Broker Capital Pacific collaborates. Click here to meet the rest of our San Francisco team. (405)ccim.net 840 0610 [email protected] PURCHASE PRICE ... $33,000,000 CAP RATE .......... 7.54% METRO AREA - Investment Highlights Cash REQUIRED .... $18,524,035 POPULATION OF OVER translates to Oklahoma City has RENTABLE SF ...........6 Buildings Totaling 185,681 SF 1,250,000 one of the lowest LAND AREA ............5 Parcels Totaling 22 Acres unemployment rates YEAR BUIlt ............2008-2014 in the U.S. >> LEASED. .93.74% Yukon Village is a well-leased 185,681 sf center, built in phases 2008-2014. Most of the occupancy is national, name- brand tenants, and it is 14 miles west of downtown Oklahoma City. This offering consists of six buildings on five parcels. Three parcels are encumbered by the same securitized loan, and two parcels are unencumbered. INVESTMENT AND LEASE HIGHLIGHTS: Low vacancy: PetSmart, Hobby Lobby, Big Lots, Kirkland’s anchored shopping center Assumable non-recourse loan of approximately $15 million at 5.25% with 30-year amortization, 10 years remaining Second phase will be completed in September. -

Oklahoma Largest Employers 1000+ Employees

Oklahoma Top Employers by # of Employees (1,000 and above) New 2021 2021 Statewide 2019 Statewide 2021 Employer Primary NAICS Employment Employment Ranking Estimate Estimate 1 *Department Of Defense (U.S.)- See breakdown at bottom 928110 69,000-70,000 68,000-69,000 2 Wal-Mart Associates Inc. 493110, 452311 38,500-39,500 32,100-32,200 493110, 492110, 3 Amazon (Fulfillment, Amazon Web Services & Whole Foods) 11,000-11,500 2,000-2,500 454110, 445110 4 Integris Health, Inc. 622110 9,600-9,700 8,800-8,900 5 Hobby Lobby Store Inc 424990 7,700-7,800 6,500-6,600 6 Oklahoma State University 611310 7,000-7,100 7,100-7,200 7 Chickasaw Nation (gaming and non-government business) 713290, 453 6,800-6,900 7,400-7,500 8 U.S. Postal Service 491110 6,700-6,800 6,800-6,900 9 Saint Francis Hospital Inc 622110 6,400-6,500 6,100-6,200 923140, 622110, 10 Department of Veterans Affairs/ U.S. Veterans Administration 6,300-6,400 5,700-5,800 621111 10 Oklahoma Department of Human Services 923130 6,300-6,400 6,300-6,400 12 University Of Oklahoma (Norman Campus) 611310 6,000-6,100 6,500-6,600 13 Mercy Health (MHM Support Services) 561110, 622110 5,900-6,000 6,200-6,300 13 OU Health Sciences Center (Board of Regents) 611310, 621111 5,900-6,000 6,700-6,800 15 Braum's Inc 722513, 311520 5,600-5,700 5,300-5,400 16 OU Medicine/ OU Medical Center 622110 5,200-5,300 4,300-4,400 17 Choctaw Nation Of OK (other businesses/non-government) 445, 447, 713 5,100-5,200 6,100-6,200 17 Tulsa Public Schools 611110 5,100-5,200 5,800-5,900 19 American Airlines, Inc. -

ANNOUNCING NEW BOARD CHAIRMAN and CLASS Allied Arts Launched the 2016 Fiscal Year Under the Leadership Ofc

Allied Arts Quarterly Newsletter Volume 9, Issue 1, Fall/Winter 2015 Enriching Our Communities ARTThrough Advancement of the Arts MATTERS ANNOUNCING NEW BOARD CHAIRMAN AND CLASS Allied Arts launched the 2016 fiscal year under the leadership ofC. Renzi Stone as chairman of the board of directors for the next two years. Stone will oversee a 96-member board of directors with a focus on implementing strategic initiatives including growing a culture of support for the arts, enhancing the Allied Arts message and improving services to Allied Arts grantees. The start of the fiscal year also welcomed 19 new members to the Allied Arts board of directors. They have already added energy, enthusiasm and unique skill sets to short- and long-term planning. C. Renzi Stone Laura Aufleger Chairman and CEO Dir. of Corp. Projects Saxum OnCue Greg Arend Graham Colton Karen Delaney Chris Doyle Mike Emmelhainz Elizabeth Hunt Managing Partner Recording Artist Community Executive Vice Operations Director Manager, Marketing Deloitte Volunteer President – Operations The Boeing Company & Communications Chesapeake Energy ITC Holdings Corp. Chris Kenney Jim Kessler Amanda Brad Krieger Travis Mason Valerie Naifeh VP & General Counsel Principal Kirkpatrick-Lawler Chairman Director Owner American Fidelity Candor Performance Realtor Arvest Bank Cushman Wakefield Naifeh Fine Jewelry Metro Mark Realtors Paul Renfrow Bill Schonacher Chuck Spicer Jerry Steward Kristin Thomas Jeff Thompson Vice President, Public President & CEO President & CEO President Vice President, President of Business Affairs, Corporate IBC Bank OU Medical System Oklahoma City Public Relations Development Administration Community College Continental Resources MTM Recognition OGE Energy Corp. ALLIED ARTS ORIENTATION As part of the annual board orientation, new members, as well as some board veterans, toured five Allied Arts member agency facilities, hearing from 16 agency representatives. -

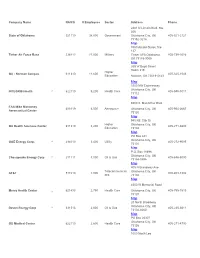

Map Map Map Map Map Map Map Map Map

Company Name NAICS # Employees Sector Address Phone 2401 N Lincoln Blvd, Ste. 206 State of Oklahoma 921110 38,000 Government Oklahoma City, OK 405-521-2121 73152-3218 Map 7460 Arnold Street, Ste 127 Tinker Air Force Base 336412 27,000 Military Tinker AFB Oklahoma, 405-739-2026 OK 73145-9005 Map 339 W Boyd Street, Room 319 Higher OU - Norman Campus 611310 11,600 405-325-1543 Education Norman, OK 73019-5143 Map 3300 NW Expressway Oklahoma City, OK INTEGRIS Health * 622110 9,200 Health Care 405-949-3011 73112 Map 6500 S. MacArthur Blvd FAA Mike Monroney 488119 6,500 Aerospace Oklahoma City, OK 405-954-2665 Aeronautical Center 73125 Map 940 NE 13th St Higher Oklahoma City, OK OU Health Sciences Center 611310 4,200 405-271-3800 Education 73104 Map PO Box 321 OklOklahomah CitCity, OK OGE Energy Corp. * 238210 3,400 Utility 405-272-9595 73101 Map P.O. Box 18496 Oklahoma City, OK Chesapeake Energy Corp * 211111 3,000 Oil & Gas 405-848-8000 73154-0496 Map 405 N Broadway Ave Telecommunicati Oklahoma City, OK AT&T 517210 3,000 800-403-3302 ons 73102 Map 4300 W Memorial Road Mercy Health Center 621493 2,750 Health Care Oklahoma City, OK 405-755-1515 * 73120 Map 20 North Broadway Oklahoma City, OK Devon Energy Corp * 331513 2,600 Oil & Gas 405-235-3611 73102-8260 Map PO Box 26307 Oklahoma City, OK OU Medical Center 622110 2,600 Health Care 405-271-4700 73126 Map 1000 North Lee SSM Health Care of Oklahoma City, OK * 622110 2,600 Health Care 405-272-7000 Oklahoma, Inc. -

2007-08 Annual Report

2007-2008 Annual Report Enriching Our Communities Through Advancement of the Arts Message from the Chairman of the Board and the President......................................................2 The Impact of Member Agencies........................................................3 Elevating the Arts................................................................................4 Investing in the Arts...........................................................................5 Allied Arts Events................................................................................6 Donor Listing...................................................................................7-11 Board of Directors.............................................................................12 Allocations Committee............................................................................13 Staff........................................................................................................14 1 Message from the Chairman of the Board and the President With support from all sectors of our community, Allied Arts reached new levels of success this year. The 2008 annual campaign broke our previous record and raised more than $2.85 million for the arts in Central Oklahoma. As a result, for the first time in our 37-year history, Allied Arts has allocated more than $2 million to our member agencies for their operational needs and educational programming. Beyond the monetary figures, what does this mean for the arts and our community? It means a culturally vibrant -

Oklahoma-Largest-Employers-List.Pdf

Oklahoma Top Employers by # of Employees (1,000 and above) New Updated! 2019 Statewide 2018 Statewide 2016 Statewide 2019 Current Employer NAICS CURRENT Employment Employment Employment State Ranking Estimate Estimate Estimate 1 Department Of Defense (U.S.)- *See breakdown on last pg. 928110 68,000 - 69,000 68,000 - 69,000 68,000 - 69,000 2 Wal-Mart Associates Inc. 493110, 452311 32,100-32,200 33,500 - 34,000 33,000 - 33,500 3 Integris Health, Inc. 622110 8,800-8,900 8,500 - 9,000 9,000 - 9,500 4 Chickasaw Nation (gaming and non-government business) 713290, 453 7,400-7,500 7,000 - 7,500 7,000 - 7,500 5 Oklahoma State University 611310 7,100-7,200 7,000 - 7,500 7,000 - 7,500 6 U.S. Postal Service 491110 6,800-6,900 6,500 - 7,000 6,500 - 7,000 7 OU Health Sciences Center (Board of Regents) 611310, 621111 6,700-6,800 6,500 - 7,000 7,000 - 7,500 8 Hobby Lobby Store Inc 424990 6,500-6,600 5,500 - 6,000 5,500 - 6,000 8 University Of Oklahoma (Norman Campus) 611310 6,500-6,600 6,500 - 7,000 7,000 - 7,500 10 Oklahoma Department of Human Services 923130 6,300-6,400 6,500 - 7,000 7,500 - 8,000 11 Mercy Health (MHM Support Services) 561110, 622110 6,200-6,300 6,000 - 6,500 6,000 - 6,500 12 Choctaw Nation Of OK (other businesses/non-government) 445, 447, 713 6,100-6,200 5,500 - 6,000 4,500 - 5,000 12 Saint Francis Hospital Inc 622110 6,100-6,200 5,500 - 6,000 5,500 - 6,000 14 Tulsa Public Schools 611110 5,800-5,900 6,000 - 6,500 6,000 - 6,500 923140, 622110, 15 Department of Veterans Affairs/ U.S. -

Pastor Rodney Fouts

2020 MISSION OF HOPE VIRTUAL CELEBRATION SEPTEMBER 10TH BOB GOFF FEATURED SPEAKER AND AUTHOR Bob Goff is the New York Times Best-Selling Author of Love Does, Everybody Always and Dream Big, the Honorary Consul to the Republic of Uganda, an attorney, and the founder of Love Does—a nonprofit human rights organization operating in Uganda, India, Nepal, Iraq and Somalia. He’s a lover of balloons, cake pops, and helping people pursue their big dreams. Bob’s greatest ambitions in life are to love others, do stuff, and, most importantly, to hold hands with his wife Sweet Maria Goff and spend time with their amazing kids. Bob calls himself a “recovering lawyer” because after practicing law for 25 years, then becoming the Hon. Consul to Uganda, he gave up his law firm to pursue writing and speaking full time. The best part has been connecting with so many people who are on a terrific adventure as well. Bob has inspired millions to dream big and make life more awesome. He is driven by a desire to help others unlock their potential to love and be loved greater. For more, check out BobGoff.com and LoveDoes.org. DARCI LYNNE SPECIAL MUSICAL GUEST Winning NBC’s “America’s Got Talent” at just 12-years old by the most votes for a final performance in the history of the show, singer/ ventriloquist Darci Lynne impresses audiences across the country with her sweetheart disposition and undeniable, show-stopping talent beyond her years. Accompanied by her musical friends including a divaesque rabbit: Petunia, a shy and soulful mouse: Oscar and a sarcastic old woman: Edna. -

HOBBY LOBBY STORES, INC., MARDEL, INC., DAVID GREEN, BARBARA GREEN, STEVE GREEN, MART GREEN, and DARSEE LETT, Respondents

No. 13-354 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— KATHLEEN SEBELIUS, SECRETARY OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, ET AL., Petitioners, v. HOBBY LOBBY STORES, INC., MARDEL, INC., DAVID GREEN, BARBARA GREEN, STEVE GREEN, MART GREEN, AND DARSEE LETT, Respondents. ———— On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit ———— BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS ———— PAUL D. CLEMENT S. KYLE DUNCAN MICHAEL H. MCGINLEY Counsel of Record BANCROFT PLLC ERIC C. RASSBACH 1919 M Street, N.W. LUKE W. GOODRICH Suite 470 MARK L. RIENZI Washington, D.C. 20036 LORI H. WINDHAM (202) 234-0090 ADÈLE AUXIER KEIM THE BECKET FUND FOR PETER M. DOBELBOWER RELIGIOUS LIBERTY General Counsel and 3000 K Street, N.W. Chief Legal Officer Suite 220 JOHN GRAHAM Washington, D.C. 20007 Assistant General Counsel (202) 349-7209 HOBBY LOBBY STORES, INC. [email protected] 7701 S.W. 44th Street Oklahoma City, OK 73179 JOSHUA D. HAWLEY (405) 745-1720 UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI SCHOOL OF LAW 323 Hulston Hall Columbia, MO 65211 (573) 882-0394 Counsel for Respondents WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. – (202) 789-0096 – WASHINGTON, D. C. 20002 QUESTION PRESENTED The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (“RFRA”), 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb et seq., provides that the government “shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion” unless that burden satisfies strict scrutiny. Id. § 2000bb-1(a), (b). Respondents are a family and their closely held businesses, which they operate according to their religious beliefs. A regulation under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act requires Respondents to provide insurance coverage for all FDA-approved “contraceptive methods [and] sterilization procedures.” 78 Fed.