Realising Botswana's Vision to Stop Hiv/Aids by 2016: The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combined Seventeenth to Twenty-Second Periodic Reports Submitted by Botswana Under Article 9 of the Convention, Due Since 2009*

United Nations CERD/C/BWA/17-22 International Convention on Distr.: General 21 July 2020 the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination Original: English English, French and Spanish only Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Combined seventeenth to twenty-second periodic reports submitted by Botswana under article 9 of the Convention, due since 2009* [Date received: 30 January 2020] * The present document is being issued without formal editing. GE.20-09810(E) CERD/C/BWA/17-22 General Information Replies to the list of issues prior to reporting CERD/C/BWA/QPR/17-22 Reply to paragraph 1 of the list of issues 1. In Botswana, the primary legislation that offers protection to human rights covered by the Convention is the Constitution. Section 3 of the Constitution accords fundamental rights and freedoms to every person on a non-discriminatory basis, including race. In addition, Section 15 of the Constitution specifically prohibits discrimination on the basis of, among others, race. 2. Since Botswana’s last report, significant legislative developments which promote and protect human rights covered by this Convention have taken place. These include the enactment of the Local Government Act of 2008, Cybercrime and Computer Related Crimes Act of 2018 and the Children’s Act of 2009. These laws incorporate the principle of non-discrimination on the basis of race in public procurement, transmission of electronic material and administration of the Children’s Act, respectively. 3. In terms of institutional framework, the Government has established a Human Rights Unit within the Ministry of Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Administration. -

MINISTRY of DEFENCE JUSTICE and SECURITY PROCUREMEN PLAN 2021-2022 MDJS HEADQUARTERS Proje Ct Code Project Name Budget Amount Ac

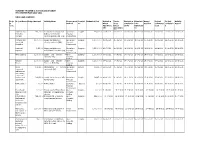

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE JUSTICE AND SECURITY PROCUREMEN PLAN 2021-2022 MDJS HEADQUARTERS Proje Project Name Budget Amount Activity Name Procurement Descipli Estimated Cost Invitation Tender Evaluation Submissio Award Project Project Activity ct Method ne Direct Close completion n for Decision Commence Completio Report Code Appointme Direct by PE Adjudicati ment n ntte Appointme on ntte Uniforms and 143,230.00 A Contract for Supply and Quotations Supplies 143,230.00 20-04-2021 08-05-2021 08-04-2021 04-12-2021 15-06-2021 15-06-2021 22-06-2021 26-08-2021 Protective Delivery of Protective Proposal Clothing Clothing and Uniform (HQ) Procurement Domestic and 1,500,000.00 Supply and delivery of Quotations Supplies 1,500,000.00 16-08-2021 31-08-2021 31-08-2021 09-06-2021 15-06-2021 15-06-2021 22-06-2021 26-08-2021 household cleaning materials (HQ) Proposal Requisites Procurement Incidental 2,350,000 Supply and delivery of Quotations Supplies 2,350,000.00 16-07-2021 08-03-2021 08-05-2021 08-09-2021 08-12-2021 16-08-2021 20-08-2021 23-08-2021 Expenses Refreshments for MDJS (HQ) Proposal Procurement Office supplies 1,500,000.00 Supply and Delivery of Open Supplies 1,500,000.00 14-06-2021 07-09-2021 14-07-2021 23-07-2021 29-07-2021 08-02-2021 23-08-2021 27-08-2021 Sationery (HQ) Domestic Bidding Genuine 1,500,000.00 Supply and Delivery of Open Supplies 1,500,000.00 14-06-2021 07-09-2021 14-07-2021 23-07-2021 29-07-2021 08-02-2021 23-08-2021 27-08-2021 Toners Toners to MDJS HQ Domestic Bidding Office 172,110.00 Maintanance of running Quotations Service -

Tender Advert

TENDER ADVERT www.etender.co.bw Botswana Prison Service - DJS/MTC/PRI 031/2020/2021 Companies are invited to express their interest in the consultancy services on conditions of service for non-uniformed (civilian) staff of the Botswana Prison Service Closing: 21 January 2021 09H00 Site Visit: Contacts Senior Superintendent Ntshebe 3611711/21 3975398/003 [email protected] Senior Superintendent Bedi 3611711/21 3975398/003 [email protected] Collection : The physical address for the collection of Tender Document is Botswana Prison Service Headquarters, Broadhurst Industrial, Plot No. 10211, next to Mafulo House at the Supplies Office. Documents may be collected during office days between 07:30 and 12:45 and from 13:45 to 16:30 with effect from 14th December 2020. Queries relating to the issuance of these documents may be addressed to: Senior Superintendent Ntshebe and Senior Superintendent Bedi at Telephone No. 3611711/21, Fax Nos. 3975398/003, Email: [email protected] and [email protected] Fee: Delivery: The names and addresses of companies should be clearly marked on the envelope. One (1) original marked “Original” plus two (2) copies marked “Copy” must be hand-delivered in sealed envelopes. Identification details to be shown on each tender offer are: “Tender No. DJS/MTC/PRI 031/2020/2021 - Expression of Interest for Consultancy Services on Conditions of Service for Non-Uniformed (Civilian) Staff of the Botswana Prison Service”. Tender offers will be submitted to The Secretary, Ministerial Tender Committee, Ministry of Defence, Justice and Security Headquarters, Central Square Building, Ground Floor, Office No. 004 at the Tender Opening Hall, Gaborone, Central Business District, Phase 2, Plot No. -

Republic of Botswana - European Community

Republic of Botswana - European Community JOINT ANNUAL REPORT 2008 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Country Performance ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Update on the political situation and political governance ................................................................. 4 1.2 Update on the economic situation and economic governance............................................................. 6 1.3 Update on the poverty and social situation......................................................................................... 10 1.4 Update on the environmental situation............................................................................................... 12 2. Overview of past and ongoing co-operation................................................................................................. 13 2.1 Reporting on the financial performance of EDF resources............................................................... 13 2.2 Reporting on General and Sector Budget Support............................................................................ 14 2.3 Project and programmes in the focal and non-focal areas................................................................ 15 2.3.1 Focal Sector: Human Resource Development......................................................................... -

Securing Recognition of Minorities and Maginalized People and Their Rights in Botswana

Evaluation: Securing Recognition of Minorities and Marginalized People and their Rights in Botswana PROJECT EVALUATION REPORT FINAL SECURING RECOGNITION OF MINORITIES AND MAGINALIZED PEOPLE AND THEIR RIGHTS IN BOTSWANA Submitted to: Minorities Rights Group International, 54 Commercial Street, London E1, 6LT, United Kingdom Submitted by: Tersara Investments P.O. Box 2139, Gaborone, Botswana, Africa 2/27/2019 This document is property of Minorities Rights Group International, a registered UK Charity and Company Limited by Guarantee and its Partners. 1 Evaluation: Securing Recognition of Minorities and Marginalized People and their Rights in Botswana Document details Client Minority Rights Group International Project title Consulting Services for the Final Evaluation: Securing Recognition of Minorities and Marginalized Peoples and their Rights in Botswana Document type Final Evaluation Document No. TS/18/MRG/EVAL00 This document Text (pgs.) Tables (No.) Figures (no.) Annexes Others comprises 17 3 7 2 N/A Document control Document version Detail Issue date TS/19/MRG/EVAL01 Project Evaluation Report FINAL for 13 June 2019 MRGI 2 Evaluation: Securing Recognition of Minorities and Marginalized People and their Rights in Botswana Contents Document details ..................................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Document control ................................................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF FIGURES (TABLES, CHARTS) -

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization. Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ijagbemi, Bayo, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 17:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196133 LAND TENURE REFORMS AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN BOTSWANA: IMPLICATIONS FOR URBANIZATION by Bayo Ijagbemi ____________________ Copyright © Bayo Ijagbemi 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Bayo Ijagbemi entitled “Land Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Thomas Park _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Stephen Lansing _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr David Killick _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Mamadou Baro Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

State of the Nation Address to the 3Rd Session of the 10Th Parliament

State of the Nation Address to the 3rd Session of the 10th Parliament 08/11/11 State of the Nation Address to the 3rd Session of the 10th Parliament State of the Nation Address to the 3rd Session of the 10th Parliament STATE OF THE NATION ADDRESS BY HIS EXCELLENCY Lt. GEN. SERETSE KHAMA IAN KHAMA PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA TO THE THIRD SESSION OF THE TENTH PARLIAMENT "BOTSWANA FIRST" 7th November 2011, GABORONE: 1. Madam Speaker, before we begin, I request that we all observe a moment of silence for those who have departed during the past year. Thank you. 2. Let me also take this opportunity to commend the Leader of the House, His Honour the Vice President, on his recent well deserved awards. In addition to the Naledi ya Botswana, which he received for his illustrious service to the nation, His Honour also did us proud when he received a World Citizen Award for his international, as well as domestic, contributions. I am sure other members will agree with me that these awards are deserving recognition of a true statesman. 3. Madam Speaker, it is a renewed privilege to address this Honourable House and the nation. This annual occasion allows us to step back and take a broader look at the critical challenges we face, along with the opportunities we can all embrace when we put the interests of our country first. 4. As I once more appear before you, I am mindful of the fact that this address will be the subject of further deliberations. -

The Big Governance Issues in Botswana

MARCH 2021 THE BIG GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN BOTSWANA A CIVIL SOCIETY SUBMISSION TO THE AFRICAN PEER REVIEW MECHANISM Contents Executive Summary 3 Acknowledgments 7 Acronyms and Abbreviations 8 What is the APRM? 10 The BAPS Process 12 Ibrahim Index of African Governance Botswana: 2020 IIAG Scores, Ranks & Trends 120 CHAPTER 1 15 Introduction CHAPTER 2 16 Human Rights CHAPTER 3 27 Separation of Powers CHAPTER 4 35 Public Service and Decentralisation CHAPTER 5 43 Citizen Participation and Economic Inclusion CHAPTER 6 51 Transparency and Accountability CHAPTER 7 61 Vulnerable Groups CHAPTER 8 70 Education CHAPTER 9 80 Sustainable Development and Natural Resource Management, Access to Land and Infrastructure CHAPTER 10 91 Food Security CHAPTER 11 98 Crime and Security CHAPTER 12 108 Foreign Policy CHAPTER 13 113 Research and Development THE BIG GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN BOTSWANA: A CIVIL SOCIETY SUBMISSION TO THE APRM 3 Executive Summary Botswana’s civil society APRM Working Group has identified 12 governance issues to be included in this submission: 1 Human Rights The implementation of domestic and international legislation has meant that basic human rights are well protected in Botswana. However, these rights are not enjoyed equally by all. Areas of concern include violence against women and children; discrimination against indigenous peoples; child labour; over reliance on and abuses by the mining sector; respect for diversity and culture; effectiveness of social protection programmes; and access to quality healthcare services. It is recommended that government develop a comprehensive national action plan on human rights that applies to both state and business. 2 Separation of Powers Political and personal interests have made separation between Botswana’s three arms of government difficult. -

A Nnual Report 2018 /19

/19 /19 2018 Report nnual A Enabling Stakeholders formulate policies, plan and make decisions. policies, planandmake formulate Enabling Stakeholders Annual Report 2018 /19 Annual Report 2018/19 LETTER TO THE MINISTER Statistics Botswana Private Bag 0024 Gaborone September 27, 2019 The Honourable Minister Kenneth O. Matambo Ministry of Finance and Economic Development Private Bag 008 Gaborone Dear Sir, In accordance with Section 25 (1) of the Statistics Act of 2009, I hereby submit the Annual Report for Statistics Botswana for the year ended 31st March 2019. Letsema G. Motsemme Statistics Botswana Board Chairman 01 Annual Report 2018/19 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 03 Executive Management 18 Botswana Demographic Survey 33 Strategic Foundations 04 Statistician General’s Review 20 Human Resources Management 34 Statistics Botswana 06 Statistics Highlights 26 Marketing of Official Statistics 38 and Brand Visibility Strategy Map Consumer Price Index (CPI) 28 Financial Statements 41 Board of Directors 08 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) 29 Appendices 68 Board Chairman’s Statement 10 International Merchandise Trade 30 Corporate Goverance 14 Formal Sector Employment 31 Internal Audit and Risk 16 Work Permits 32 Management 02 Annual Report 2018/19 INTRODUCTION About Statistics Botswana Statistics Botswana (SB) was set up as a Other responsibilities are as follows: parastatal under the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development. The Organization a. Producing and providing Government, the operates under the 2009 Statistics Act. The private sector, parastatals and international Organization is under the oversight direction organizations, the civil society and the of the Board of Directors, membership which general public with statistical information is drawn from Government, the Private Sector for evidence based decision-making, policy and Non-Governmental Organizations. -

Government Gazette

REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Vol. XV, No. 64 GABORONE 21st October, 1977. CONTENTS Page Presidential Awards — G.N. No. 598of 1977 ......................................................................................... 854 Acting Appointment - Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Mineral Resources and Water Affairs G.N. No. 599 of 1977 ......................................................................................................................... 854 Acting Appointment - Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Finance and Development Planning — G.N. No. No. 600 of 1977 ......................................................................................................................... 855 Acting Appointment - Auditor-General — G.N. No. 601 of 1977......................................................... 855 Appointment of General Registration Period — G.N. No. 602 of 1977 ................................................ 855 Application for Change in Establishment of School — G.N. No. 603 of 1977 ......................................................................................................................... 856 G.N. No. 604 of 1977 ......................................................................................................................... 856 G.N. No. 605 of 1977 ......................................................................................................................... 856 G.N. No. 606 of 1977 ........................................................................................................................ -

His Excellency

International Day of Democracy Parliamentary Conference on Democracy in Africa organized jointly by the Inter-Parliamentary Union and the Parliament of Botswana Gaborone, Botswana, 14 – 16 September 2009 SUMMARY RECORDS DIRECTOR OF CEREMONY (MRS MONICA MPHUSU): His Excellency the President of Botswana, Lieutenant General Seretse Khama Ian Khama, IPU President, Dr Theo-Ben Gurirab, Deputy Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Ms Thokozani Khupe, Former President of Togo Mr Yawovi Agboyibo, Members of the diplomatic community, President and founder of Community Development Foundation Ms Graça Machel, Honourable Speakers, Cabinet Ministers, Permanent Secretary to the President, Honourable Members of Parliament, Dikgosi, if at all they are here, Distinguished Guests. I wish to welcome you to the Inter-Parliamentary Union Conference. It is an honour and privilege to us as a nation to have been given the opportunity to host this conference especially during our election year. This conference comes at a time when local politicians are criss-crossing the country as the election date approaches. They are begging the general public to employ them. They want to be given five year contract. Your Excellencies, some of you would have observed from our local media how vibrant and robust our democracy is. This demonstrates the political maturity that our society has achieved over the past 43 years since we attained independence. Your Excellencies, it is now my singular honour and privilege to introduce our host, the Speaker of the National Assembly of the Republic -

CIMS Newsletter, Vol 5, Issue 2, 2013

Volume 5 • Issue 2 MAY 2013 Administration of Justice Newsletter E- GOVERNANCE TEAM TAKES WEBSITE TO STAFF ..................5 Gauging Of Stations ........6 INSIDE THIS ISSUE MR G. NTHOMIWA APPOINTED A JUDGE OF THE HIGH COURT ......3 DEFENCE ATTACHES VISIT THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE .........9 HIGH COURT JUDGES VISIT TANZANIAN JUDICIAL SERVICE COMMISSION DTCB .........4 DELEGATION VISITS BOTSWANA...................... 12 MOCHUDI MAGISTRATE COURT- A SUCCESS DURING THE GAUGING OF MARCH- SEPTEMBER 2012......18 19 Ask the Guru!.... MR G. NTHOMIWA Editorial APPOINTED A JUDGE Vision he CIMS team would like to commend the good work that the users all over the courts continue “Access to Justice to give in. Users your never ending, T for All by 2016.” relentless commitment towards CRMS is beginning to bear fruits as evidenced by the October 2012-March 2013 gauging results. When the lowest court in rating used to garner as little as 35% , this time the last court has garnered a comfortable 53%. And the highest court this time has also broken record. At 89%, this is the highest ever for the number one station in the history of gauging. This is remarkable!!! However we have not completely won the battle, our criminal cases and scanning are still the areas that need our special Mission attention. What needs to be done? Please see the full article by Ms G Dintsi. To uphold human rights, Democracy and the rule of Ms King covers the Legal Year opening celebration. Please enjoy the article and law in accordance with the the splash of pictures that accompany the Constitution of Botswana article.