Investigation of the Consonant Endings of the Chaoshan Dialect: a Result of Language Contact and Horizontal Transmission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater Bay Area Logistics Markets and Opportunities Colliers Radar Logistics | Industrial Services | South China | 29 May 2020

COLLIERS RADAR LOGISTICS | INDUSTRIAL SERVICES | SOUTH CHINA | 29 MAY 2020 Rosanna Tang Head of Research | Hong Kong SAR and Southern China +852 2822 0514 [email protected] Jay Zhong Senior Analyst | Research | Guangzhou +86 20 3819 3851 [email protected] Yifan Yu Assistant Manager | Research | Shenzhen +86 755 8825 8668 [email protected] Justin Yi Senior Analyst | Research | Shenzhen +86 755 8825 8600 [email protected] GREATER BAY AREA LOGISTICS MARKETS AND OPPORTUNITIES COLLIERS RADAR LOGISTICS | INDUSTRIAL SERVICES | SOUTH CHINA | 29 MAY 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INSIGHTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 3 MAP OF GBA LOGISTICS MARKETS AND RECOMMENDED CITIES 4 MAP OF GBA TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM 5 LOGISTICS INDUSTRY SUPPLY AND DEMAND 6 NEW GROWTH POTENTIAL AREA IN GBA LOGISTICS 7 GBA LOGISTICS CLUSTER – ZHUHAI-ZHONGSHAN-JIANGMEN 8 GBA LOGISTICS CLUSTER – SHENZHEN-DONGGUAN-HUIZHOU 10 GBA LOGISTICS CLUSTER – GUANGZHOU-FOSHAN-ZHAOQING 12 2 COLLIERS RADAR LOGISTICS | INDUSTRIAL SERVICES | SOUTH CHINA | 29 MAY 2020 Insights & Recommendations RECOMMENDED CITIES This report identifies three logistics Zhuhai Zhongshan Jiangmen clusters from the mainland Greater Bay The Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau We expect Zhongshan will be The manufacturing sector is Area (GBA)* cities and among these Bridge Zhuhai strengthens the a logistics hub with the now the largest contributor clusters highlights five recommended marine and logistics completion of the Shenzhen- to Jiangmen’s overall GDP. logistics cities for occupiers and investors. integration with Hong Kong Zhongshan Bridge, planned The government aims to build the city into a coastal logistics Zhuhai-Zhongshan-Jiangmen: and Macau. for 2024, connecting the east and west banks of the Peral center and West Guangdong’s > Zhuhai-Zhongshan-Jiangmen’s existing River. -

Some Notes on Implosive Consonants in Nyangatom

Studies in Ethiopian Languages, 5 (2016), 11-20 Some Notes on Implosive Consonants in Nyangatom Moges Yigezu (Addis Ababa University) [email protected] Abstract Nyangatom is a member of the Teso-Turkana cluster within the Eastern-Niltoic group of languages (Vossen 1982) and is spoken in Ethiopia, in the lower Omo valley, by approximately 25,000 speakers (CSA 2008). While there is a detailed description on the Turkana variety spoken in Kenya (Heine 1980, Dimmendaal 1983) there are few grammatical sketches on the Nyangatom variety (Dimmendaal (2007) and Kadanya & Schroder (2011)) spoken in Ethiopia. The status of implosives in the Teso-Turkana group in general and in Nyangatom in particular has not been investigated more clearly and different authors have reached different conclusions in the past. Heine (1980), for instance, recorded implosives as having a phonemic status in Turkana while Dimmendaal (1983) has described implosives in Turkana as variants of their voiced counterparts. In Nyangatom the grammatical sketches published so far have not identified implosive consonants as phonemes of the language. The current contribution gives a preliminary phonological analysis of implosives in Nyangatom with some comparative-historical notes and claim that implosives are full-fledged phonemes in Nyangatom and the opposition is between voiceless stops and implosives while the voiced stops are virtually absent from the phonological system. 1 Introduction Nyangatom belongs to the Teso- Turkana dialect cluster that consists of four major groups and spread over four East African countries, namely, the Nyangatom in Ethiopia, the Toposa in Southern Sudan, the Turkana in Kenya, and the Karamojong in North Eastern Uganda. -

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

Recovering Xiangshan Culture and the Joint Local Development

Asian Social Science; Vol. 10, No. 11; 2014 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Recovering Xiangshan Culture and the Joint Local Development Ruihui Han1 1 Humanities School, Jinan University, Zhuhai, Guangdong Province, China Correspondence: Ruihui Han, Humanities School, Jinan University, Zhuhai, Guangdong Province, China. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 21, 2014 Accepted: May 5, 2014 Online Published: May 30, 2014 doi:10.5539/ass.v10n11p77 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v10n11p77 Abstract Xiangshan culture is a beautiful flower in Chinese modern history. The paper analyzes the origin, development, waning and influence of it. It is innovating and pioneering, and has the features of inclusiveness, mercantilism and its own historical heritage. Recovering Xiangshan culture has significant meaning for the local development of economy, society and culture. And that would also provide the positive driving force for the historic progress of all the China. Keywords: Xiangshan culture, Xiangshanese, modernization, social development, cultural development 1. Introduction The requirement of regional integration of Zhongshan, Zhuhai and Jiangmen often appeared in recent years. For example, the bill for combining Zhongshan, Zhuhai and Jiangmen as Zhujiang City was tabled by Guangdong Zhigong Party committee in January, 2014. The same bill was also tabled by the Macau member of CPPCC(Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference) in March, 2013. The city administration partition hinders the regional development of Xiangshan. Integration of the three cities can improve the cooperation with the destruction of administration partition. The bills are thought as a good idea but cannot be realized easily. -

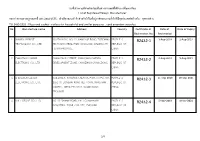

No. Manufacture Name Address Country Certificate of Registration

รายชื่อโรงงานทที่ าผลิตภัณฑ์ในตา่ งประเทศทไี่ ดร้ ับการขึ้นทะเบียน List of Registered Foreign Manufacturer ขอบขา่ ยตามมาตรฐานเลขท ี่ มอก.2432-2555 : เตา้ เสียบและเตา้ รับส าหรับใชใ้ นทอี่ ยู่อาศัยและงานทวั่ ไปทมี่ จี ุดประสงค์คล้ายกัน : ชดุ สายพ่วง TIS 2432-2555 : Plugs and socket - outlets for household and similar purposes : cord extention setsrules No. Manufacture name Address Country Certificate of Date of Date of Expiry Registration No. Registration 1 XIAMEN SEEBEST SOUTH BLDG, NO. 31 XIANGYUE ROAD, TORCH HI- PEOPLE' S R2432-1 3-Aug-2018 2-Aug-2021 TECHNOLOGY CO., LTD. TECH INDUSTRIAL PARK (XIANG'AN), XIAMEN CITY, REPUBLIC OF FUJIAN PROVINCE CHINA 2 CHAOZHOU NANKE CHANGCHUN STREET, XIANGQIAO GARDEN PEOPLE' S R2432-2 6-Aug-2018 5-Aug-2021 ELECTRONIC CO., LTD. DEVELOPMENT ZONE, CHAOZHOU GUANGDONG REPUBLIC OF CHINA 3 SHENZHEN CLEVER BUILDING 8, BAIWANG CREATIVE PARK (UTPC), NO. PEOPLE' S R2432-3 11-Sep-2018 10-Sep-2021 ELECTRONIC CO., LTD. 1051 OF SONGBAI ROAD XILI TOWN, NANSHAN REPUBLIC OF DISTRICT, SHENZHEN CITY, GUANGDONG CHINA PROVINCE 4 BULL GROUP CO., LTD. NO. 32 SHAHAI ROAD, EAST GUANHAIWEI PEOPLE' S R2432-4 5-Nov-2018 4-Nov-2021 INDUSTRIAL ZONE, CIXI CITY, ZHEJIANG REPUBLIC OF CHINA 1/4 รายชื่อโรงงานทที่ าผลิตภัณฑ์ในตา่ งประเทศทไี่ ดร้ ับการขึ้นทะเบียน List of Registered Foreign Manufacturer ขอบขา่ ยตามมาตรฐานเลขท ี่ มอก.2432-2555 : เตา้ เสียบและเตา้ รับส าหรับใชใ้ นทอี่ ยู่อาศัยและงานทวั่ ไปทมี่ จี ุดประสงค์คล้ายกัน : ชดุ สายพ่วง TIS 2432-2555 : Plugs and socket - outlets for household and similar purposes : cord extention setsrules No. Manufacture name Address Country Certificate of Date of Date of Expiry Registration No. Registration 5 DONGGUAN GWTEE ELECTRIC GETIAN INDUSTRIAL ZONE, CHAOLANG VILLAGE, PEOPLE' S R2432-5 16-Nov-2018 15-Nov-2021 MANUFACTURE CO., LTD. -

Analysis of CO2 Emission in Guangdong Province, China

Feasibility Study of CCUS-Readiness in Guangdong Province, China (GDCCSR) Final Report: Part 1 Analysis of CO2 Emission in Guangdong Province, China GDCCSR-GIEC Team March 2013 Authors (GDCCSR-GIEC Team) Daiqing Zhao Cuiping Liao Ying Huang, Hongxu Guo Li Li, Weigang Liu (Guangzhou Institute of Energy Conversion, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou, China) For comments or queries please contact: Prof. Cuiping Liao [email protected] Announcement This is the first part of the final report of the project “Feasibility Study of CCS-Readiness in Guangdong (GDCCSR)”, which is funded by the Strategic Programme Fund of the UK Foreign & Commonwealth Office joint with the Global CCS Institute. The report is written based on published data mainly. The views in this report are the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Guangzhou Institute of Energy Conversion, nor of the funding organizations. The complete list of the project reports are as follows: Part 1 Analysis of CO2 emission in Guangdong Province, China. Part 2 Assessment of CO2 Storage Potential for Guangdong Province, China. Part 3 CO2 Mitigation Potential and Cost Analysis of CCS in Power Sector in Guangdong Province, China. Part 4 Techno-economic and Commercial Opportunities for CCS-Ready Plants in Guangdong Province, China. Part 5 CCUS Capacity Building and Public Awareness in Guangdong Province, China Part 6 CCUS Development Roadmap Study for Guangdong Province, China Analysis of CO2 Emission in Guangdong Province Contents Background for the Report .........................................................................................2 -

11Th International Conference on Chaozhou Studies

11TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CHAOZHOU STUDIES AUGUST 17 – 19, 2015 UNIVERSITY OF VICTORIA VICTORIA, BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA PHOTO BY UVIC PHOTO SERVICES UVIC PHOTO BY PHOTO 八 潮 第十 N IO T 年 N E V T H N E O 1 C 8 L t h A T N E O I O T C A H N E R W E T N I 11TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CHAOZHOU STUDIES A 痦⼧♧㾉惐㷖㕂꣢灇雭⠔11TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CHAOZHOU STUDIES Revised Program & Itinerary Revised Program & Itinerary Due to the absence of a number of scheduled present- Due to the absence of a number of scheduled present- ers, we have had to make changes to the conference ers, we have had to make changes to the conference program. Please see the revised schedule & itinerary for program. Please see the revised schedule & itinerary for updated times and locations. updated times and locations. HUANG Ting will not be able to present the keynote HUANG Ting will not be able to present the keynote speech during the Opening Plenary. Instead, we will speech during the Opening Plenary. Instead, we will hear from ZHOU Shaochan. A short biography is hear from ZHOU Shaochan. A short biography is included below. included below. The following sessions have been combined and will be The following sessions have been combined and will be at 11:30 am on Tuesday: at 11:30 am on Tuesday: • Religion and Characters will be in Fraser 157 • Religion and Characters will be in Fraser 157 • Dialect #1 and Dialect #2 will be in Fraser 158 • Dialect #1 and Dialect #2 will be in Fraser 158 Professor ZHOU Shaochuan, PhD in History ワ㼱䊛侅䱇⾎〷㷖⽇㡦 Professor ZHOU Shaochuan is from Shantou, Guangdong Province in China, ワ㼱䊛⽇㡦勻荈䎛⚎寀㣢梡⟣ currently a professor and doctoral tutor at School of Chinese Ancient Books ⻌❩䋗薴㣐㷖〢硂♸⠛絡俒⻊灇 and Traditional Culture, Beijing Normal University. -

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation - Chinese Producers of Wooden Cabinets and Vanities Company Name Company Information Company Name: A Shipping A Shipping Street Address: Room 1102, No. 288 Building No 4., Wuhua Road, Hongkou City: Shanghai Company Name: AA Cabinetry AA Cabinetry Street Address: Fanzhong Road Minzhong Town City: Zhongshan Company Name: Achiever Import and Export Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 103 Taihe Road Gaoming Achiever Import And Export Co., City: Foshan Ltd. Country: PRC Phone: 0757-88828138 Company Name: Adornus Cabinetry Street Address: No.1 Man Xing Road Adornus Cabinetry City: Manshan Town, Lingang District Country: PRC Company Name: Aershin Cabinet Street Address: No.88 Xingyuan Avenue City: Rugao Aershin Cabinet Province/State: Jiangsu Country: PRC Phone: 13801858741 Website: http://www.aershin.com/i14470-m28456.htmIS Company Name: Air Sea Transport Street Address: 10F No. 71, Sung Chiang Road Air Sea Transport City: Taipei Country: Taiwan Company Name: All Ways Forwarding (PRe) Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 268 South Zhongshan Rd. All Ways Forwarding (China) Co., City: Huangpu Ltd. Zip Code: 200010 Country: PRC Company Name: All Ways Logistics International (Asia Pacific) LLC. Street Address: Room 1106, No. 969 South, Zhongshan Road All Ways Logisitcs Asia City: Shanghai Country: PRC Company Name: Allan Street Address: No.188, Fengtai Road City: Hefei Allan Province/State: Anhui Zip Code: 23041 Country: PRC Company Name: Alliance Asia Co Lim Street Address: 2176 Rm100710 F Ho King Ctr No 2 6 Fa Yuen Street Alliance Asia Co Li City: Mongkok Country: PRC Company Name: ALMI Shipping and Logistics Street Address: Room 601 No. -

Shop Direct Factory List Dec 18

Factory Factory Address Country Sector FTE No. workers % Male % Female ESSENTIAL CLOTHING LTD Akulichala, Sakashhor, Maddha Para, Kaliakor, Gazipur, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 669 55% 45% NANTONG AIKE GARMENTS COMPANY LTD Group 14, Huanchi Village, Jiangan Town, Rugao City, Jaingsu Province, China CHINA Garments 159 22% 78% DEEKAY KNITWEARS LTD SF No. 229, Karaipudhur, Arulpuram, Palladam Road, Tirupur, 641605, Tamil Nadu, India INDIA Garments 129 57% 43% HD4U No. 8, Yijiang Road, Lianhang Economic Development Zone, Haining CHINA Home Textiles 98 45% 55% AIRSPRUNG BEDS LTD Canal Road, Canal Road Industrial Estate, Trowbridge, Wiltshire, BA14 8RQ, United Kingdom UK Furniture 398 83% 17% ASIAN LEATHERS LIMITED Asian House, E. M. Bypass, Kasba, Kolkata, 700017, India INDIA Accessories 978 77% 23% AMAN KNITTINGS LIMITED Nazimnagar, Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 1708 60% 30% V K FASHION LTD formerly STYLEWISE LTD Unit 5, 99 Bridge Road, Leicester, LE5 3LD, United Kingdom UK Garments 51 43% 57% AMAN GRAPHIC & DESIGN LTD. Najim Nagar, Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 3260 40% 60% WENZHOU SUNRISE INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD. Floor 2, 1 Building Qiangqiang Group, Shanghui Industrial Zone, Louqiao Street, Ouhai, Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, China CHINA Accessories 716 58% 42% AMAZING EXPORTS CORPORATION - UNIT I Sf No. 105, Valayankadu, P. Vadugapal Ayam Post, Dharapuram Road, Palladam, 541664, India INDIA Garments 490 53% 47% ANDRA JEWELS LTD 7 Clive Avenue, Hastings, East Sussex, TN35 5LD, United Kingdom UK Accessories 68 CAVENDISH UPHOLSTERY LIMITED Mayfield Mill, Briercliffe Road, Chorley Lancashire PR6 0DA, United Kingdom UK Furniture 33 66% 34% FUZHOU BEST ART & CRAFTS CO., LTD No. 3 Building, Lifu Plastic, Nanshanyang Industrial Zone, Baisha Town, Minhou, Fuzhou, China CHINA Homewares 44 41% 59% HUAHONG HOLDING GROUP No. -

The Acquisition of Plosives and Implosives by a Fulfulde-Speaking Child Aged from 5 to 10

ICPhS XVII Regular Session Hong Kong, 17-21 August 2011 THE ACQUISITION OF PLOSIVES AND IMPLOSIVES BY A FULFULDE-SPEAKING CHILD AGED1 FROM 5 TO 10;29 MONTHS Ibrahima Cissé, Didier Demolin & Nathalie Vallée Gipsa-lab, CNRS, Grenoble Université, France [email protected] ABSTRACT half an hour twice a month from the age of 5 months to 10 months 29 days in his family (in the This paper reports an analysis of the acquisition of village of Nokara). M was recorded interacting plosives and implosives by a Fulfulde monolingual with his mother during “normal” daily life child aged from 5 months to 10 months and 29 activities. M is growing up in a Fulfulde days. Analyses revealed that before 11 months the monolingual family and village. child was making use of complex consonant-like implosives and prenasal plosives. We provided 2.1.2. The adult data new aerodynamic analyses of adult‟s implosive /ɓ/. These aerodynamic data revealed that in Fulfulde The adult data on implosives are from I., a 28 this phoneme exhibits both voiced and voiceless years old male native speaker of Fulfulde from allophones. Nokara. A list of words containing implosives was recorded. Each word was recorded 3 times using Keywords: acquisition of plosives and implosives, an EVA2® portable workstation. This portable Fulfulde workstation provides simultaneously synchronized intra-oral pressure (Ps) measured in hPa and an 1. INTRODUCTION audio waveform of speech. The audio recording Research on child phonological acquisition focuses sampling was at 44100KHz. on several aspects of the emergence of speech production in children: prosody [7], segments [2], 2.2. -

A Patois of Saintonge: Descriptive Analysis of an Idiolect and Assessment of Present State of Saintongeais

70-13,996 CHIDAINE, John Gabriel, 1922- A PATOIS OF SAINTONGE: DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS OF AN IDIOLECT AND ASSESSMENT OF PRESENT STATE OF SAINTONGEAIS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 Language and Literature, linguistics University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan •3 COPYRIGHT BY JOHN GABRIEL CHIDAINE 1970 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED A PATOIS OF SAINTONGE : DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS OF AN IDIOLECT AND ASSESSMENT OF PRESENT STATE OF SAINTONGEAIS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Gabriel Chidaine, B.A., M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by Depart w .. w PLEASE NOTE: Not original copy. Some pages have indistinct print. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS PREFACE The number of studies which have been undertaken with regard to the southwestern dialects of the langue d'oi'l area is astonishingly small. Most deal with diachronic considerations. As for the dialect of Saintonge only a few articles are available. This whole area, which until a few generations ago contained a variety of apparently closely related patois or dialects— such as Aunisian, Saintongeais, and others in Lower Poitou— , is today for the most part devoid of them. All traces of a local speech have now’ disappeared from Aunis. And in Saintonge, patois speakers are very limited as to their number even in the most remote villages. The present study consists of three distinct and unequal phases: one pertaining to the discovering and gethering of an adequate sample of Saintongeais patois, as it is spoken today* another presenting a synchronic analysis of its most pertinent features; and, finally, one attempting to interpret the results of this analysis in the light of time and area dimensions. -

Strongly Heterogeneous Transmission of COVID–19 in Mainland China: Local and Regional Variation

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.10.20033852; this version posted March 16, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Strongly heterogeneous transmission of COVID–19 in mainland China: local and regional variation Yuke Wang, MSc1, Peter Teunis, PhD1 March 10, 2020 Summary Background The outbreak of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) started in the city of Wuhan, China, with a period of rapid initial spread. Transmission on a regional and then national scale was promoted by intense travel during the holiday period of the Chinese New Year. We studied the variation in transmission of COVID-19, locally in Wuhan, as well as on a larger spatial scale, among different cities and even among provinces in mainland China. Methods In addition to reported numbers of new cases, we have been able to assemble detailed contact data for some of the initial clusters of COVID-19. This enabled estimation of the serial interval for clinical cases, as well as reproduction numbers for small and large regions. Findings We estimated the average serial interval was 4·8 days. For early transmission in Wuhan, any infectious case produced as many as four new cases, transmission outside Wuhan was less in- tense, with reproduction numbers below two. During the rapid growth phase of the outbreak the region of Wuhan city acted as a hot spot, generating new cases upon contact, while locally, in other provinces, transmission was low.