American Grape Growing and Wine Making (1883)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BULLETIN No, 48

TEXAS AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATIONS. BULLETIN No, 48 . t h e : i POSTOFFICE: COLLEGE STATION, BRAZOS CO., T E X A S. AUSTIN: BEN C. JONES & CO., STATE PRINTERS 1 8 9 8 [ 1145 ] TEXAS AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATIONS. OFFICERS. GOVERNING BOARD. (BOARD OF DIRECTORS A. & M. COLLEGE.) HON. F. A. REICHARDT, President..................................................................Houston. HON. W . R. CAvITT.................................................................................................. Bryan. HON. F. P. HOLLAND............................................................................................... Dallas. HON. CHAS. ROGAN .......... ............................................................................Brown wood. HON. JEFF. JOHNSON............................................................................................... Austin. HON. MARION SANSOM................................•.......................................................Alvarado. STATION STAFF. THE PRESIDENT OF THE COLLEGE. J. H. CONNELL, M. SC......................................................................................... Director. H. II. HARRINGTON, M . SC'..................................................................................Chemist. M. FRANCIS, D. V . M ...................................................................................Veterinarian . R. H. PRICE, B. S ....................................................................................... Horticulturist. B. C. PITTuCK. B. S. A..................................................................................Agriculturist. -

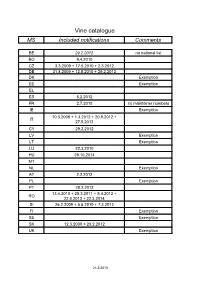

Vine Catalogue MS Included Notifications Comments

Vine catalogue MS Included notifications Comments BE 29.2.2012 no national list BG 9.4.2010 CZ 3.3.2009 + 17.5.2010 + 2.3.2012 DE 31.8.2009 + 12.5.2010 + 29.2.2012 DK Exemption EE Exemption EL ES 8.2.2012 FR 2.7.2010 no maintainer numbers IE Exemption 10.3.2008 + 1.3.2012 + 20.9.2012 + IT 27.5.2013 CY 29.2.2012 LV Exemption LT Exemption LU 22.3.2010 HU 29.10.2014 MT NL Exemption AT 2.2.2012 PL Exemption PT 28.2.2012 13.4.2010 + 25.3.2011 + 5.4.2012 + RO 22.4.2013 + 22.3.2014 SI 26.2.2009 + 5.5.2010 + 7.3.2012 FI Exemption SE Exemption SK 12.3.2009 + 20.2.2012 UK Exemption 21.5.2015 Common catalogue of varieties of vine 1 2 3 4 5 Known synonyms Variety Clone Maintainer Observations in other MS A Abbuoto N. IT 1 B, wine, pas de Abondant B FR matériel certifiable Abouriou B FR B, wine 603, 604 FR B, wine Abrusco N. IT 15 Accent 1 Gm DE 771 N Acolon CZ 1160 N We 725 DE 765 B, table, pas de Admirable de Courtiller B FR matériel certifiable Afuz Ali = Regina Agiorgitiko CY 163 wine, black Aglianico del vulture N. I – VCR 11, I – VCR 14 IT 2 I - Unimi-vitis-AGV VV401, I - Unimi-vitis- IT 33 AGV VV404 I – VCR 7, I – VCR 2, I – Glianica, Glianico, Aglianico N. VCR 13, I – VCR 23, I – IT 2 wine VCR 111, I – VCR 106, I Ellanico, Ellenico – VCR 109, I – VCR 103 I - AV 02, I - AV 05, I - AV 09, I - BN 2.09.014, IT 31 wine I - BN 2.09.025 I - Unimi-vitis-AGT VV411, I - Unimi-vitis- IT 33 wine AGTB VV421 I - Ampelos TEA 22, I - IT 60 wine Ampelos TEA 23 I - CRSA - Regione Puglia D382, I - CRSA - IT 66 wine Regione Puglia D386 Aglianicone N. -

Cassis Twenty‐Three Shades of White

8/20/2019 Cassis Twenty‐three Shades of White Elizabeth Gabay MW Wine Scholar Guild, 14 August 2019 Where in France? Cassis 1 8/20/2019 Cold Mistral Mont Ste Victoire Massif Ste Baume Humid maritime winds Cassis The Calanques are deep fjords 2 8/20/2019 Deep under sea trenches near the coast brings cold water and cool air up into the calanques 215 hectares of Cassis vineyards Cap Canaille, the highest maritime cliff in Europe at 394m Cassis is like a vast amphitheatre facing towards the sea. 3 8/20/2019 Only around 10% of the region has vineyards which can be divided into two 2. ‘Les Janots’ along a valley areas. orientated southwest‐north east and stretching from 1. ‘Le Plan’ located Bagnol to the Janots. The in the western part slopes face south east. Sites of Cassis and the called ‘Rompides’, ‘Pignier’ least intensly (gentle slopes). planted. The vineyards are on 3. «Revestel» flatter lands. under Cap Canaille the ‘Janots’ rise up to the slopes These vineyards and rocky cliffs of ‘La Saoupe’ generally face east and ‘Le Baou Redon’. south east. These vineyards generally face west north west. Gravel, large ‘galets’ Reef limestone and limestone Clay and Calcaire limestone Three Zones 1. in the west, a flat surface bordering Cassis in the direction of Bédoule, a low calcareous brown soil developed on alluvium. 4 8/20/2019 2. the valley of Rompides, Bagnol Janots, through the Crown of Charlemagne. It is a basin with two types of exposure, South‐West and North‐East, and a variable gradient, increasing on the south‐east side of the Rompides. -

Determining the Classification of Vine Varieties Has Become Difficult to Understand Because of the Large Whereas Article 31

31 . 12 . 81 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 381 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 3800/81 of 16 December 1981 determining the classification of vine varieties THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/ 70 ( 4), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 591 /80 ( 5), sets out the classification of vine varieties ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the classification of vine varieties should be substantially altered for a large number of administrative units, on the basis of experience and of studies concerning suitability for cultivation; . Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organization of the Whereas the provisions of Regulation ( EEC) market in wine C1), as last amended by Regulation No 2005/70 have been amended several times since its ( EEC) No 3577/81 ( 2), and in particular Article 31 ( 4) thereof, adoption ; whereas the wording of the said Regulation has become difficult to understand because of the large number of amendments ; whereas account must be taken of the consolidation of Regulations ( EEC) No Whereas Article 31 of Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 816/70 ( 6) and ( EEC) No 1388/70 ( 7) in Regulations provides for the classification of vine varieties approved ( EEC) No 337/79 and ( EEC) No 347/79 ; whereas, in for cultivation in the Community ; whereas those vine view of this situation, Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/70 varieties -

European Commission

29.9.2020 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union C 321/47 OTHER ACTS EUROPEAN COMMISSION Publication of a communication of approval of a standard amendment to the product specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 17(2) and (3) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 (2020/C 321/09) This notice is published in accordance with Article 17(5) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 (1). COMMUNICATION OF A STANDARD AMENDMENT TO THE SINGLE DOCUMENT ‘VAUCLUSE’ PGI-FR-A1209-AM01 Submitted on: 2.7.2020 DESCRIPTION OF AND REASONS FOR THE APPROVED AMENDMENT 1. Description of the wine(s) Additional information on the colour of wines has been inserted in point 3.3 ‘Evaluation of the products' organoleptic characteristics’ in order to add detail to the description of the various products. The details in question have also been added to the Single Document under the heading ‘Description of the wine(s)’. 2. Geographical area Point 4.1 of Chapter I of the specification has been updated with a formal amendment to the description of the geographical area. It now specifies the year of the Geographic Code (the national reference stating municipalities per department) in listing the municipalities included in each additional geographical designation. The relevant Geographic Code is the one published in 2019. The names of some municipalities have been corrected but there has been no change to the composition of the geographical area. This amendment does not affect the Single Document. 3. Vine varieties In Chapter I(5) of the specification, the following 16 varieties have been added to those listed for the production of wines eligible for the ‘Vaucluse’ PGI: ‘Artaban N, Assyrtiko B, Cabernet Blanc B, Cabernet Cortis N, Floreal B, Monarch N, Muscaris B, Nebbiolo N, Pinotage N, Prior N, Soreli B, Souvignier Gris G, Verdejo B, Vidoc N, Voltis B and Xinomavro N.’ (1) OJ L 9, 11.1.2019, p. -

Our Native Grape. Grapes and Their Culture. Also Descriptive List of Old

GREEN MOUNTAIN, Our Native Grape. Grapes and Their Culture ALSO DESCRIPTIVE LIST OF OLD AND NEW VARIETIES, PUBLISHED BY C MITZKY & CO. 1893- / W. W. MORRISON, PRINTER, 95-99 EAST MAIN STREET ROCHESTER, N. Y. \ ./v/^f Entered according to Act ot Congress, in the year 1893, by C. MITZKY & CO., Rochester, N. Y., in the office of tlie Librarian of Congress, at Washington, 1). C. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. :.^ ^ 5 •o •A ' * Introduction. RAPE GROWING is fast becoming a great industry. Its importance is almost incalculable, and it should re- ceive every reasonable encouragement. It is not our intention in this manual, ' OUR NATIVE GRAPE," to make known new theories, but to improve on those already in practice. Since the publication ot former works on this subject a great many changes have taken place ; new destructive diseases have ap- peared, insects, so detrimental to Grapevines, have increased, making greater vigilance and study neces- sary. / New varieties of Grapes have sprung up with great rapidity Many labor-saving tools have been introduced, in fact. Grape culture of the present time is a vast improvement on the Grape culture of years ago. The material herein contained has been gathered by the assistance of friends all over the country in all parts of the United States, and compiled and arranged that not alone our own ex- perience, but that of the best experts in the country, may serve as a guide to the advancement of Grape culture. We have spared neither time or expense to make this work as complete as possible. With all our efforts, however, we feel compelled to ask forbearance for our shortcom- ings and mild judgment for our imperfections. -

Sixth International Congress on Mountain and Steep Slope Viticulture

SEXTO CONGRESO INTERNACIONAL SOBRE VITICULTURA DE MONTAÑA Y EN FUERTE PENDIENTE SIXTH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS ON MOUNTAIN AND STEEP SLOPE VITICULTURE San Cristobal de la Laguna (Isla de Tenerife) – España 26 – 28 de Abril de 2018 “Viticultura heroica: de la uva al vino a través de recorridos de sostenibilidad y calidad" “Heroic viticulture: from grape to win through sustainability and quality” ACTOS PROCEEDINGS COMUNICACIONES ORALES ORAL COMMUNICATIONS ISBN 978-88-902330-5-0 PATROCINIOS Generating Innovation Between Practice and Research SEXTO CONGRESO INTERNACIONAL SOBRE VITICULTURA DE MONTAÑA Y EN FUERTE PENDIENTE SIXTH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS ON MOUNTAIN AND STEEP SLOPE VITICULTURE SESIÓN I SESSION I Mecanización y viticultura de precisión en los viñedos en fuerte pendiente Mechanization and precision viticulture for steep slope vineyard PATROCINIOS Generating Innovation Between Practice and Research Steep slope viticulture in germany – dealing with present and future challenges Mathias Scheidweiler1, Manfred Stoll1, Hans-Peter Schwarz2, Andreas Kurth3, Simone Mueller Loose3, Larissa Strub3, Gergely Szolnoki3, and Hans-Reiner Schultz4 1) Dept. of General and Organic Viticulture, Geisenheim University, Von-Lade-Strasse, 65366 Geisenheim, Germany. [email protected] 2) Department of Engineering, Geisenheim University 3) Department of Business Administration and Market Research, Geisenheim University 4) President, Geisenheim University ABSTRACT For many reasons the future viability of steep slope viticulture is under threat, with changing climatic conditions and a high a ratio of costs to revenue some of the most immediate concerns. Within a range of research topics, steep slope viticulture is still a major focus at the University of Geisenheim. We will discuss various aspects of consumer´s recognition, viticultural constraints in terms of climatic adaptations (water requirements, training system or fruit composition) as well as innovations in mechanisation in the context of future challenges of steep slope viticulture. -

9, 2017 at Mount Snow Grand Summit Hotel in West Dover, Vermont 2,497

2,497 Total Entries Judged April 7 - 9, 2017 at Mount Snow Grand Summit Hotel in West Dover, Vermont 2,497....................total entries 50 different categories and included an astonishing array of vari- etals and wine styles. New this year was the addition of the Apple 506.......................wine flights Hard Cider and Perry category to meet demand from hobbyists. Kit 759............. total judging hours wines competed alongside fresh-grape entries in this blind tasting. Entries were awarded gold, silver, bronze and best of show medals 50................... American states based on the average score given by the judging panel. The Grand 6............... Canadian provinces Champion Wine award was the top overall scoring wine across all categories and is being renamed this year the “Gene Spaziani Grand 7............................. Countries Champion Wine” in recognition of our longtime judging director. The Club of the Year was given to the club whose members won the most medals and the Retailer of the Year and U-Vint of the rom April 7 to 9, 2017, a total of 2,497 different wines were Year awards were given to the winemaking supply stores whose judged at the Grand Summit Hotel and Conference Center at customers outperformed other similar shops. Finally the Winemaker Mount Snow Resort in West Dover, Vermont. This year’s of the Year award was given to the individual entrant who has the f competition was again the largest wine competition highest average score across their top 5 scoring wines in the com- of its kind in the world. The 2,497 entries arrived from hobby petition. -

Canada-EU Wine and Spirits Agreement

6.2.2004 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 35/3 AGREEMENT between the European Community and Canada on trade in wines and spirit drinks THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY, hereafter referred to as ‘the Community', and CANADA, hereafter jointly referred to as ‘the Contracting Parties', RECOGNISING that the Contracting Parties desire to establish closer links in the wine and spirits sector, DESIROUS of creating more favourable conditions for the harmonious development of trade in wine and spirit drinks on the basis of equality and mutual benefit, HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS: TITLE I — ‘labelling' shall mean any tag, brand, mark, pictorial or other descriptive matter, written, printed, stencilled, marked, embossed or impressed on, or attached to, a INITIAL PROVISIONS container of wine or a spirit drink, Article 1 — ‘WTO Agreement' refers to the Marrakesh Agreement establishing the World Trade Organisation, Objectives 1. The Contracting Parties shall, on the basis of — ‘TRIPs Agreement' refers to the Agreement on trade-related non-discrimination and reciprocity, facilitate and promote aspects of intellectual property rights, which is contained trade in wines and spirit drinks produced in Canada and the in Annex 1C to the WTO Agreement, Community, on the conditions provided for in this Agreement. 2. The Contracting Parties shall take all reasonable measures — ‘1989 Agreement' refers to the Agreement between the to ensure that the obligations laid down in this Agreement are European Economic Community and Canada concerning fulfilled and that the objectives set out in this Agreement are trade and commerce in alcoholic beverages concluded on attained. 28 February 1989. Article 2 2. -

Télécharger Le

Publié au BO-AGRI le 12 décembre 2019 Cahier des charges de l’appellation d’origine contrôlée « AJACCIO » homologué par arrêté du 6 décembre 2019, publié au JORF du 8 décembre 2019 CHAPITRE Ier I. - Nom de l’appellation Seuls peuvent prétendre à l’appellation d’origine contrôlée « Ajaccio », initialement reconnue par le décret du 21 avril 1971 sous le nom « Coteaux d’Ajaccio », les vins répondant aux dispositions particulières fixées ci-après. II. - Dénominations géographiques et mentions complémentaires Pas de disposition particulière. III. - Couleur et types de produit L’appellation d’origine contrôlée « Ajaccio » est réservée aux vins tranquilles blancs, rouges et rosés. IV. - Aires et zones dans lesquelles différentes opérations sont réalisées 1°- Aire géographique La récolte des raisins, la vinification et l’élaboration des vins sont assurées sur le territoire des communes suivantes du département de la Corse-du-Sud : Afa, Ajaccio, Alata, Albitreccia, Ambiegna, Appietto, Arbori, Arro, Bastelicaccia, Calcatoggio, Canelle, Carbuccia, Cargèse, Casaglione, Casalabriva, Cauro, Coggia, Cognocoli-Monticchi, Coti-Chiavari, Cuttoli-Corticchiato, Eccica-Suarella, Grosseto-Prugna, Ocana, Peri, Piana, Pietrosella, Pila-Canale, Saint-André-d’Orcino, Sari-d’Orcino, Sarrola-Carcopino, Serra-di-Ferro, Tavaco, Valle-di-Mezzana, Vero, Vico et Villanova. 2°- Aire parcellaire délimitée Les vins sont issus exclusivement des vignes situées dans l’aire parcellaire de production telle qu’approuvée par l’Institut national de l’origine et de la qualité lors des la séances du comité national compétent du 27 mai 1982 et du 19 juin 2019. L’Institut national de l’origine et de la qualité dépose auprès des mairies des communes mentionnées au 1° les documents graphiques établissant les limites parcellaires de l’aire de production ainsi approuvées. -

Corot Noir’™ Grape B.I

NUMBER 159, 2006 ISSN 0362-0069 New York’s Food and Life Sciences Bulletin New York State Agricultural Experiment Station, Geneva, a Division of the New York State College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, A Statutory College of the State University, at Cornell University ‘Corot noir’™ Grape B.I. Reisch1, R.S. Luce1, Bruce Bordelon2, and T. Henick-Kling3 ‘Corot noir’™ (pronounced “kor-oh nwahr”) is a mid to late season red wine grape suit- able for either blending or the production of varietal wines. The wine has a deep red color and attractive cherry and berry fruit aromas. Its tannin structure is complete from the front of the mouth to the back, with big soft tannins. The vine is moderately win- ter hardy and moderately resistant to fungal diseases. ORIGIN DESCRIPTION ‘Corot noir’™ was developed by the Own-rooted vines grown in phylloxera grape breeding program at Cornell Univer- (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae Fitch) infested soils sity, New York State Agricultural Experi- have been long-lived and vigorous. To date, ment Station. It is a complex interspecifi c there have been no indications that graft- hybrid red wine grape resulting from a ing onto rootstocks is necessary, but caution cross made in 1970 between Seyve Villard should be exercised in soils where phyllox- 18-307 and ‘Steuben’ (Fig. 1). From 250 era is more of a problem than in the Finger seeds, 160 seedlings were grown in a nurs- Lakes of New York. ery then transplanted to a seedling vine- Vines of ‘Corot noir’ have been ob- yard in 1975. Thirty-three seedlings were served in plantings at the New York State fermented for evaluation of wine character- Agricultural Experiment Station and in- istics, and about fi fteen were propagated for formation on productivity, diseases, pests, further testing. -

AWC 2013 Competition Results

AWC 2013 Competition Results name cl class score medal ingredients Saunders, Edward A Aperitif Sherry 19 Gold & Cellarcraft International - Specialty Series Kit - Creamy Sherry Best in Class Pearson, Tony A Aperitif Sherry 18.5 Gold 100% California Palomino Grapes Sweetness (3) Solera Beattie, David A Aperitif Sherry 16.5 Silver Made from an assorted variety of white wines added to a sherry carboy and finally bottled in 2012. Thornton, Bill A Aperitif Sherry 16.5 Silver 1999 Sherry Kit, Wine Kitz, Vidal 1999, Palamino Concentrate. Proportions unknown (records lost) Goodhew, Ron A Aperitif Sherry 16 Silver Winexpert Speciale Sherry Rennie, Bill A Aperitif Sherry 16 Silver Dry Fino style - Solera aged. Ingredients generally have been inexpensive white kits, fermented with flor yeast. Solera is 13 years old. Kroitzsch, Axel A Aperitif Sherry 15.5 Bronze Herbed Aperitif Quast, Mervin A Aperitif Sherry 15.5 Bronze 100% malvasia Bianca (California - Franicas) Mayer, Glen B Aperitif 16.5 Silver & herbed Aperitif Best in Class Kroitzsch, Axel B Aperitif 15.5 Bronze Aperitif Rennie, Bill B Aperitif 14 Bronze Herbed "red" vermouth. Solera aged - Ingredients have been slightly ozidized wines, herbs and spices include wormwood, chinchona bark, anise, woodruff, bitter orange. Fortified with gin. Starr, John B Aperitif 14 Bronze 50% fresh blackberries, 25% NY Muscat fresh grapes, 25% ruby port kit- Winekitz speciality Series Saunders, Edward B Aperitif 13 RJ Spagnols - Restricted Quantity Series Kit - Muscat Mott, Elayne B Aperitif 12 85% plum wine