Mipham Gyatso Rinpoche's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery

Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery Dominique Townsend Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Dominique Townsend All rights reserved ABSTRACT Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery Dominique Townsend This dissertation investigates the relationships between Buddhism and culture as exemplified at Mindroling Monastery. Focusing on the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, I argue that Mindroling was a seminal religio-cultural institution that played a key role in cultivating the ruling elite class during a critical moment of Tibet’s history. This analysis demonstrates that the connections between Buddhism and high culture have been salient throughout the history of Buddhism, rendering the project relevant to a broad range of fields within Asian Studies and the Study of Religion. As the first extensive Western-language study of Mindroling, this project employs an interdisciplinary methodology combining historical, sociological, cultural and religious studies, and makes use of diverse Tibetan sources. Mindroling was founded in 1676 with ties to Tibet’s nobility and the Fifth Dalai Lama’s newly centralized government. It was a center for elite education until the twentieth century, and in this regard it was comparable to a Western university where young members of the nobility spent two to four years training in the arts and sciences and being shaped for positions of authority. This comparison serves to highlight commonalities between distant and familiar educational models and undercuts the tendency to diminish Tibetan culture to an exoticized imagining of Buddhism as a purely ascetic, world renouncing tradition. -

The Lhasa Jokhang – Is the World's Oldest Timber Frame Building in Tibet? André Alexander*

The Lhasa Jokhang – is the world's oldest timber frame building in Tibet? * André Alexander Abstract In questo articolo sono presentati i risultati di un’indagine condotta sul più antico tempio buddista del Tibet, il Lhasa Jokhang, fondato nel 639 (circa). L’edificio, nonostante l’iscrizione nella World Heritage List dell’UNESCO, ha subito diversi abusi a causa dei rifacimenti urbanistici degli ultimi anni. The Buddhist temple known to the Tibetans today as Lhasa Tsuklakhang, to the Chinese as Dajiao-si and to the English-speaking world as the Lhasa Jokhang, represents a key element in Tibetan history. Its foundation falls in the dynamic period of the first half of the seventh century AD that saw the consolidation of the Tibetan empire and the earliest documented formation of Tibetan culture and society, as expressed through the introduction of Buddhism, the creation of written script based on Indian scripts and the establishment of a law code. In the Tibetan cultural and religious tradition, the Jokhang temple's importance has been continuously celebrated soon after its foundation. The temple also gave name and raison d'etre to the city of Lhasa (“place of the Gods") The paper attempts to show that the seventh century core of the Lhasa Jokhang has survived virtually unaltered for 13 centuries. Furthermore, this core building assumes highly significant importance for the fact that it represents authentic pan-Indian temple construction technologies that have survived in Indian cultural regions only as archaeological remains or rock-carved copies. 1. Introduction – context of the archaeological research The research presented in this paper has been made possible under a cooperation between the Lhasa City Cultural Relics Bureau and the German NGO, Tibet Heritage Fund (THF). -

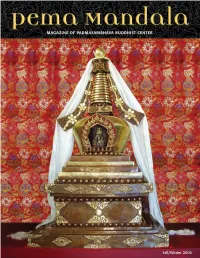

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

The Prayer, the Priest and the Tsenpo: an Early Buddhist Narrative from Dunhuang

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 30 Number 1–2 2007 (2009) The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc. As a peer-reviewed journal, it welcomes scholarly contributions pertaining to all facets of Buddhist EDITORIAL BOARD Studies. JIABS is published twice yearly. KELLNER Birgit Manuscripts should preferably be sub- KRASSER Helmut mitted as e-mail attachments to: [email protected] as one single fi le, Joint Editors complete with footnotes and references, in two diff erent formats: in PDF-format, BUSWELL Robert and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- Document-Format (created e.g. by Open CHEN Jinhua Offi ce). COLLINS Steven Address books for review to: COX Collet JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur- und GÓMEZ Luis O. Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Prinz-Eugen- HARRISON Paul Strasse 8-10, A-1040 Wien, AUSTRIA VON HINÜBER Oskar Address subscription orders and dues, changes of address, and business corre- JACKSON Roger spondence (including advertising orders) JAINI Padmanabh S. to: KATSURA Shōryū Dr Jérôme Ducor, IABS Treasurer Dept of Oriental Languages and Cultures KUO Li-ying Anthropole LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. University of Lausanne MACDONALD Alexander CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland email: [email protected] SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina Web: http://www.iabsinfo.net SEYFORT RUEGG David Fax: +41 21 692 29 35 SHARF Robert Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 40 per STEINKELLNER Ernst year for individuals and USD 70 per year for libraries and other institutions. For TILLEMANS Tom informations on membership in IABS, see back cover. -

Escape to Lhasa Strategic Partner

4 Nights Incentive Programme Escape to Lhasa Strategic Partner Country Name Lhasa, the heart and soul of Tibet, is a city of wonders. The visits to different sites in Lhasa would be an overwhelming experience. Potala Palace has been the focus of the travelers for centuries. It is the cardinal landmark and a structure of massive proportion. Similarly, Norbulingka is the summer palace of His Holiness Dalai Lama. Drepung Monastery is one of the world’s largest and most intact monasteries, Jokhang temple the heart of Tibet and Barkhor Market is the place to get the necessary resources for locals as well as souvenirs for tourists. At the end of this trip we visit the Samye Monastery, a place without which no journey to Tibet is complete. StrategicCountryPartner Name Day 1 Arrive in Lhasa Country Name Day 1 o Morning After a warm welcome at Gonggar Airport (3570m) in Lhasa, transfer to the hotel. Distance (Airport to Lhasa): 62kms/ 32 miles Drive Time: 1 hour approx. Altitude: 3,490 m/ 11,450 ft. o Leisure for acclimatization Lhasa is a city of wonders that contains many culturally significant Tibetan Buddhist religious sites and lies in a valley next to the Lhasa River. StrategicCountryPartner Name Day 2 In Lhasa Country Name Day 2 o Morning: Set out to visit Sera and Drepung Monasteries Founded in 1419, Sera Monastery is one of the “great three” Gelukpa university monasteries in Tibet. 5km north of Lhasa, the Sera Monastery’s setting is one of the prettiest in Lhasa. The Drepung Monastery houses many cultural relics, making it more beautiful and giving it more historical significance. -

Inner Mongolia

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: CHN30730 Country: China Date: 13 October 2006 Keywords: CHN30730 – Tibetan Buddhism – Government Treatment – Inner Mongolia This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Please provide some background information on this Huang Jiao group. 2. Please provide information on the Chinese government’s treatment of this group, especially in Mongolia. RESPONSE 1. Please provide some background information on this Huang Jiao group. The file indicates that the applicant is from Tongliao, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. The applicant claims to practice a religion from Tibet similar to Buddhism. According to the US Department of State, most ethnic Mongolians practice Tibetan Buddhism (US Department of State 2006, International Religious Freedom Report 2006 – China, 15 September, Section 1 – Attachment 1). Huang Jiao means yellow religion in Chinese. One reference to huang jiao was found amongst the sources consulted. The article published in The Drama Review in 1989 reports that huang jiao is the yellow sect of Tibetan Buddhism (Liuyi, Qu et al 1989, ‘The Yi: Human Evolution Theatre’, The Drama Review, Vol 33, No 3, Autumn, p.105 – Attachment 2). The yellow sect of Tibetan Buddhism is more commonly known as Gelug but is also known as Geluk, Gelugpa, Gelukpa, Gelug pa, Geluk pa and the Yellow Hat sect. -

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts By Ramin Etesami A thesis submitted to the graduate school in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the International Buddhist College, Thailand March, 20 Abstract The Tulku institution is a unique characteristic of Tibetan Buddhism with a central role in this tradition, to the extent that it is present in almost every aspect of Tibet’s culture and tradition. However, despite this central role and the scope and diversity of the socio-religious aspects of the institution, only a few studies have so far been conducted to shed light on it. On the other hand, an aura of sacredness; distorted pictures projected by the media and film industries;political propaganda and misinformation; and tendencies to follow a pattern of cult behavior; have made the Tulku institution a highly controversial topic for research; and consequently, an objective study of the institution based on a critical approach is difficult. The current research is an attempt to comprehensively examine different dimensions of the Tulku tradition with an emphasis on the issue of its orthodoxy with respect to the core doctrines of Buddhism and the social implications of the practice. In this research, extreme caution has been practiced to firstly, avoid any kind of bias rooted in faith and belief; and secondly, to follow a scientific methodology in reviewing evidence and scriptures related to the research topic. Through a comprehensive study of historical accounts, core Buddhist texts and hagiographic literature, this study has found that while the basic Buddhist doctrines allow the possibility for a Buddhist teacher or an advanced practitioner to “return back to accomplish his tasks, the lack of any historical precedence which can be viewed as a typical example of the practice in early Buddhism makes the issue of its orthodoxy equivocal and relative. -

The Tibetan Translation of the Indian Buddhist Epistemological Corpus

187 The Tibetan Translation of the Indian Buddhist Epistemological Corpus Pascale Hugon* As Buddhism was transmitted to Tibet, a huge number of texts were translated from Sanskrit, Chinese and other Asian languages into Tibetan. Epistemological treatises composed by In dian Buddhist scholars – works focusing on the nature of »valid cognition« and exploring peripheral issues of philosophy of mind, logic, and language – were, from the very beginning, part of the translated corpus, and had a profound impact on Tibetan intellectual history. This paper looks into the progression of the translation of such works in the two phases of the diffusion of Buddhism to Tibet – the early phase in the seventh to the ninth centuries and the later phase starting in the late tenth century – on the basis of lists of translated works in various catalogues compiled in these two phases and the contents of the section »epistemo logy« of canonical collections (Tenjur). The paper inquires into the prerogatives that directed the choice of works that were translated, the broader or narrower diffusion of existing trans lations, and also highlights preferences regarding which works were studied in particular contexts. I consider in particular the contribution of the famous »Great translator«, Ngok Loden Shérap (rngog blo ldan shes rab, 10591109), who was also a pioneer exegete, and discuss some of the practicalities and methodology in the translation process, touching on the question of terminology and translation style. The paper also reflects on the status of translated works as authentic sources by proxy, and correlatively, on the impact of mistaken translations and the strategies developed to avoid them. -

Please Click This Link

5, rond -point du Vignoble SAKYA TSECHEN LING F-67520 KUTTOLSHEIM (FRANCE) INSTITUT EUROP ÉEN DE Téléphone : +33 (0)3 88 87 73 80 BOUDDHISME TIBÉTAIN Secrétariat : +33 (0)3 88 87 73 80 FONDATEUR : KHENCHEN GU ÉSH É SHÉRAB E-mail : [email protected] GYALTSEN AMIPA RINPOCHÉ Site web : http://sakyatsechenling.eu Kuttolsheim, December 1 st 2019 Seminars at SAKYA TSECHEN LING Kuttolsheim in 2020 24 - 26 January: Prayer Sampa Lhundrupma - Khenpo Tashi Sampa Lhundrupma, The Prayer to Guru Rinpoche That Spontaneously Fulfills All Wishes , is a prayer that forms the seventh chapter of Le'u Dünma, a terma revealed in the fourteenth century. It was given to the prince Mutri Tsenpo, the King of Gungthang, and son of King Trisong Detsen, by Padmasambhava as he was leaving for the land of the rakshasa demons in the southwest. Tulku Zangpo Drakpa revealed this famous and powerful prayer. 14 - 16 February: The 37 practices of Bodhisattvas, part II - Khenpo Tashi The mind training text, 37 Bodhisattva Practices , was written in Tibet in the fourteenth century by the Sakya master Togme Zangpo. Togme Zangpo was well known as being an actual Bodhisattva, and his text is studied by all of the various Tibetan traditions. It is in fact a great classic of Tibetan literature and for centuries has inspired many practitioners on the path of Mahayana, as it offers many concrete cues to integrate every experience of life in the spiritual path. 22 February: GUTOR & Mahakala day 16:00 Mahakala ritual with Gutor , a ritual to eliminate negativities accumulated during the past year and to build protection for the upcoming new Tibetan year. -

A Brief Introduction to Buddhism and the Sakya Tradition

A brief introduction to Buddhism and the Sakya tradition © 2016 Copyright © 2016 Chödung Karmo Translation Group www.chodungkarmo.org International Buddhist Academy Tinchuli–Boudha P.O. Box 23034 Kathmandu, Nepal www.internationalbuddhistacademy.org Contents Preface 5 1. Why Buddhism? 7 2. Buddhism 101 9 2.1. The basics of Buddhism 9 2.2. The Buddha, the Awakened One 12 2.3. His teaching: the Four Noble Truths 14 3. Tibetan Buddhism: compassion and skillful means 21 4. The Sakya tradition 25 4.1. A brief history 25 4.2. The teachings of the Sakya school 28 5. Appendices 35 5.1. A brief overview of different paths to awakening 35 5.2. Two short texts on Mahayana Mind Training 39 5.3. A mini-glossary of important terms 43 5.4. Some reference books 46 5 Preface This booklet is the first of what we hope will become a small series of introductory volumes on Buddhism in thought and practice. This volume was prepared by Christian Bernert, a member of the Chödung Karmo Translation Group, and is meant for interested newcomers with little or no background knowledge about Buddhism. It provides important information on the life of Buddha Shakyamuni, the founder of our tradition, and his teachings, and introduces the reader to the world of Tibetan Buddhism and the Sakya tradition in particular. It also includes the translation of two short yet profound texts on mind training characteristic of this school. We thank everyone for their contributions towards this publication, in particular Lama Rinchen Gyaltsen, Ven. Ngawang Tenzin, and Julia Stenzel for their comments and suggestions, Steven Rhodes for the editing, Cristina Vanza for the cover design, and the Khenchen Appey Foundation for its generous support. -

How to Do Prostration by Sakya Pandita

How to do prostration By Sakya Pandita NAMO MANJUSHRIYE NAMO SUSHIRIYE NAMA UTAMA SHIRIYE SVAHA NAMO GURU BHYE NAMO BUDDHA YA NAMO DHARMA YA NAMO SANGHA YA By offering prostrations toward the exalted Three Jewels, may I and all sentient beings be purified of our negativities and obscurations. Folding the two hands evenly, may we attain the integration of method and wisdom. Placing folded hands on the crown, may we be born in the exalted pure realm of Sukhavati. Placing folded hands at the forehead, may we purify all negative deeds and obscurations of the body. Placing folded hands at the throat, may we purify all negative deeds and obscurations of the voice. Placing folded hands at the heart, may we purify all negative deeds and obscurations of the mind. Separating the folded hands, may we be able to perform the benefit of beings through the two rupakaya. Touching the two knees to the floor, may we gradually travel the five paths and ten stages. Placing the forehead upon the ground, may we attain the eleventh stage of perpetual radiance. Bending and stretching the four limbs, may we spontaneously accomplish the four holy activities of peace, increase, magnetizing, and subjugation of negative forces. Bending and stretching all veins and channels, may we untie the vein knots. Straightening and stretching the backbone and central channel, may we be able to insert all airs without exception into the central channel. Rising from the floor, may we be able to attain liberation by not abiding in samsara. 1 Repeatedly offering this prostration many times, may we be able to rescue sentient beings by not abiding in peace. -

Bulletin of Tibetology

Bulletin of Tibetology VOLUME 45 NO. 1 2009 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK, SIKKIM The Bulletin of Tibetology seeks to serve the specialist as well as the general reader with an interest in the field of study. The motif portraying the Stupa on the mountains suggests the dimensions of the field. Bulletin of Tibetology VOLUME 45 NO. 1 2009 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK, SIKKIM Patron HIS EXCELLENCY SHRI BALMIKI PRASAD SINGH, THE GOVERNOR OF SIKKIM Advisor TASHI DENSAPA, DIRECTOR NIT Editorial Board FRANZ-KARL EHRHARD ACHARYA SAMTEN GYATSO SAUL MULLARD BRIGITTE STEINMANN TASHI TSERING MARK TURIN ROBERTO VITALI Editor ANNA BALIKCI-DENJONGPA Guest Editor for Present Issue DANIEL A. HIRSHBERG Assistant Editors TSULTSEM GYATSO ACHARYA THUPTEN TENZING The Bulletin of Tibetology is published bi-annually by the Director, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok, Sikkim. Annual subscription rates: South Asia, Rs150. Overseas, $20. Correspondence concerning bulletin subscriptions, changes of address, missing issues etc., to: Administrative Assistant, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok 737102, Sikkim, India ([email protected]). Editorial correspondence should be sent to the Editor at the same address. Submission guidelines. We welcome submission of articles on any subject of the history, language, art, culture and religion of the people of the Tibetan cultural area although we would particularly welcome articles focusing on Sikkim, Bhutan and the Eastern Himalayas. Articles should be in English or Tibetan, submitted by email or on CD along with a hard copy and should not exceed 5000 words in length. The views expressed in the Bulletin of Tibetology are those of the contributors alone and not the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology.