Bulletin of Tibetology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Paper on Tibetan Culture

http://english.people.com.cn/features/tibetpaper/tibeta.html White Paper on Tibetan Culture Following is the full text of the white paper on "The Development of Tibetan Culture" released by the Information Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China June 22: Foreword I. The Spoken and Written Tibetan Language Is Widely Studied and Used, and Being Developed II. Cultural Relics and Ancient Books and Records Are Well Preserved and Utilized III. Folk Customs and Freedom of Religious Belief Are Respected and Protected IV. Culture and Art Are Being Inherited and Developed in an All- Round Way V. Tibetan Studies Are Flourishing, and Tibetan Medicine and Pharmacology Have Taken On a New Lease of Life VI. Popular Education Makes a Historic Leap VII. The News and Publishing, Broadcasting, Film and Television Industries Are Developing Rapidly Conclusion Foreword China is a united multi-ethnic country. As a member of the big family of the Chinese nation, the Tibetan people have created and developed their brilliant and distinctive culture during a long history of continuous exchanges and contacts with other ethnic groups, all of whom have assimilated and promoted each other's cultures. Tibetan culture has all along been a dazzling pearl in the treasure- house of Chinese culture as well as that of the world as a whole. The gradual merger of the Tubo culture of the Yalong Valley in the middle part of the basin of the Yarlung Zangbo River, and the ancient Shang-Shung culture of the western part of the Qinghai- Tibet Plateau formed the native Tibetan culture. -

The Prayer, the Priest and the Tsenpo: an Early Buddhist Narrative from Dunhuang

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 30 Number 1–2 2007 (2009) The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc. As a peer-reviewed journal, it welcomes scholarly contributions pertaining to all facets of Buddhist EDITORIAL BOARD Studies. JIABS is published twice yearly. KELLNER Birgit Manuscripts should preferably be sub- KRASSER Helmut mitted as e-mail attachments to: [email protected] as one single fi le, Joint Editors complete with footnotes and references, in two diff erent formats: in PDF-format, BUSWELL Robert and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- Document-Format (created e.g. by Open CHEN Jinhua Offi ce). COLLINS Steven Address books for review to: COX Collet JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur- und GÓMEZ Luis O. Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Prinz-Eugen- HARRISON Paul Strasse 8-10, A-1040 Wien, AUSTRIA VON HINÜBER Oskar Address subscription orders and dues, changes of address, and business corre- JACKSON Roger spondence (including advertising orders) JAINI Padmanabh S. to: KATSURA Shōryū Dr Jérôme Ducor, IABS Treasurer Dept of Oriental Languages and Cultures KUO Li-ying Anthropole LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. University of Lausanne MACDONALD Alexander CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland email: [email protected] SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina Web: http://www.iabsinfo.net SEYFORT RUEGG David Fax: +41 21 692 29 35 SHARF Robert Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 40 per STEINKELLNER Ernst year for individuals and USD 70 per year for libraries and other institutions. For TILLEMANS Tom informations on membership in IABS, see back cover. -

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts By Ramin Etesami A thesis submitted to the graduate school in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the International Buddhist College, Thailand March, 20 Abstract The Tulku institution is a unique characteristic of Tibetan Buddhism with a central role in this tradition, to the extent that it is present in almost every aspect of Tibet’s culture and tradition. However, despite this central role and the scope and diversity of the socio-religious aspects of the institution, only a few studies have so far been conducted to shed light on it. On the other hand, an aura of sacredness; distorted pictures projected by the media and film industries;political propaganda and misinformation; and tendencies to follow a pattern of cult behavior; have made the Tulku institution a highly controversial topic for research; and consequently, an objective study of the institution based on a critical approach is difficult. The current research is an attempt to comprehensively examine different dimensions of the Tulku tradition with an emphasis on the issue of its orthodoxy with respect to the core doctrines of Buddhism and the social implications of the practice. In this research, extreme caution has been practiced to firstly, avoid any kind of bias rooted in faith and belief; and secondly, to follow a scientific methodology in reviewing evidence and scriptures related to the research topic. Through a comprehensive study of historical accounts, core Buddhist texts and hagiographic literature, this study has found that while the basic Buddhist doctrines allow the possibility for a Buddhist teacher or an advanced practitioner to “return back to accomplish his tasks, the lack of any historical precedence which can be viewed as a typical example of the practice in early Buddhism makes the issue of its orthodoxy equivocal and relative. -

Buddhism and Medicine in Tibet: Origins, Ethics, and Tradition

Buddhism and Medicine in Tibet: Origins, Ethics, and Tradition William A. McGrath Herndon, Virginia B.Sc., University of Virginia, 2007 M.A., University of Virginia, 2015 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia May, 2017 Abstract This dissertation claims that the turn of the fourteenth century marks a previously unrecognized period of intellectual unification and standardization in the Tibetan medical tradition. Prior to this time, approaches to healing in Tibet were fragmented, variegated, and incommensurable—an intellectual environment in which lineages of tantric diviners and scholarly literati came to both influence and compete with the schools of clinical physicians. Careful engagement with recently published manuscripts reveals that centuries of translation, assimilation, and intellectual development culminated in the unification of these lineages in the seminal work of the Tibetan tradition, the Four Tantras, by the end of the thirteenth century. The Drangti family of physicians—having adopted the Four Tantras and its corpus of supplementary literature from the Yutok school—established a curriculum for their dissemination at Sakya monastery, redacting the Four Tantras as a scripture distinct from the Eighteen Partial Branches addenda. Primarily focusing on the literary contributions made by the Drangti family at the Sakya Medical House, the present dissertation demonstrates the process -

Magic, Healing and Ethics in Tibetan Buddhism

Magic, Healing and Ethics in Tibetan Buddhism Sam van Schaik (The British Library) Aris Lecture in Tibetan and Himalayan Studies Wolfson College, Oxford, 16 November 2018 I first met Michael Aris in 1997, while I was in the midst of my doctoral work on Jigme LingPa and had recently moved to Oxford. Michael resPonded graciously to my awkward requests for advice and helP, meeting with me in his college rooms, and rePlying to numerous emails, which I still have printed out and on file (this was the 90s, when we used to print out emails). Michael also made a concerted effort to have the Bodleian order an obscure Dzogchen text at my request, giving me a glimPse into his work as an advocate of Tibetan Studies at Oxford. And though I knew Anthony Aris less well, I met him several times here in Oxford and elsewhere, and he was always a warm and generous Presence. When I came to Oxford I was already familiar with Michael’s work, esPecially his book on Jigme LingPa’s account of India in the eighteenth century, and his study of the treasure revealer Pema LingPa. Michael’s aPProach, symPathetic yet critical, ProPerly cautious but not afraid to exPlore new connections and interPretations, was also an insPiration to me. I hoPe to reflect a little bit of that sPirit in this evening’s talk. What is magic? So, this evening I’m going to talk about magic. But what is ‘magic’ anyway? Most of us have an idea of what the word means, but it is notoriously difficult to define. -

Population and Society in Contemporary Tibet

Population and Society in Contemporary Tibet Rong MA Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2011 ISBN 978-962-209-202-0 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co. Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents List of Tables vii List of Figures xiii Foreword by Melvyn Goldstein xv Acknowledgments xvii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Geographic Distribution and Changes in the Tibetan Population 17 of China 3. The Han Population in the Tibetan-inhabited Areas 41 4. Analyses of the Population Structure in the Tibetan Autonomous 71 Region 5. Migration in the Tibetan Autonomous Region 97 6. Economic Patterns and Transitions in the Tibet Autonomous 137 Region 7. Income and Consumption of Rural and Urban Residents in the 191 Tibetan Autonomous Region 8. Tibetan Spouse Selection and Marriage 241 vi Contents 9. Educational Development in the Tibet Autonomous Region 273 10. Residential Patterns and the Social Contacts between Han and 327 Tibetan Residents in Urban Lhasa Notes 357 References (Chinese and English) 369 Glossary of Terms 385 Index 387 List of Tables Table 2.1. The Geographic Distribution of Ethnic Tibetans in China 21 Table 2.2. -

Tibet Was Never Part of China Before 1950: Examples of Authoritative Pre-1949 Chinese Documents That Prove It

Article Tibet was Never Part of China Before 1950: Examples of Authoritative pre-1949 Chinese Documents that Prove It Hon-Shiang LAU Abstract The claim ‘Tibet has been part of China since antiquity’ is crucial for the PRC to legitimize her annexation of Tibet in 1950. However, the vast amount of China’s pre-1949 primary-source records consistently indicate that this claim is false. This paper presents a very small sample of these records from the Ming and the Qing dynasties to illustrate how they unequivocally contradict PRC’s claim. he People’s Republic of China (PRC) claims that ‘Tibet has been part of China T since antiquity西藏自古以来就是中国的一部分.’ The Central Tibet Administration (CTA), based in Dharamshala in India, refuses to accede to this claim, and this refusal by the CTA is used by the PRC as: 1. A prima facie proof of CTA’s betrayal to her motherland (i.e., China), and 2. Justification for not negotiating with the CTA or the Dalai Lama. Why must the PRC’s insist that ‘Tibet has been part of China since antiquity’? China is a signatory to the 1918 League-of-Nations Covenants and the 1945 United- Nations Charter; both documents prohibit future (i.e., post-1918) territorial acquisitions via conquest. Moreover, the PRC incessantly paints a sorry picture of Prof. Hon-Shiang LAU is an eminent Chinese scholar and was Chair Professor at the City University of Hong Kong. He retired in 2011 and has since then pursued research on Chinese government records and practices. His study of Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, and Manchu period official records show that Tibet was never treated as part of China. -

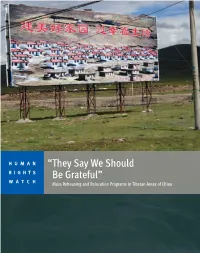

Report on Tibetan Herder Relocation Programs

HUMAN “They Say We Should RIGHTS Be Grateful” WATCH Mass Rehousing and Relocation Programs in Tibetan Areas of China “They Say We Should Be Grateful” Mass Rehousing and Relocation Programs in Tibetan Areas of China Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0336 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2013 ISBN: 978-1-62313-0336 “They Say We Should Be Grateful” Mass Rehousing and Relocation Programs in Tibetan Areas of China Map: Tibetan Autonomous Areas within the People’s Republic of China ............................... i Glossary ............................................................................................................................ -

Bulletin of Tibetology Seeks to Serve the Specialist As Welt As the General Reader with an Inter Est in This Field of Study

Bulletin of Tilbettology ~ NEW SERIES 1997 No.2 7 Augu.t" 1997 filKKIM REliEARI:H INBTITUft OF TIBETOLD&Y .&AN&TaI( ••IKIUM The Bulletin of Tibetology seeks to serve the specialist as welt as the general reader with an inter est in this field of study. The motif portraying the stupa on the mountain suggests the dimensions of the field. EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor Tashi Tobden I.A.S. Member Shri Bhajagovinda Ghosh Member Sonam Gyatso Dpkham Member Acharya Samten Gyatso Member Dr. Rigzin Ngodup Bulletin of Tn.lbetology NEW SERIES 1997 No.2 7 Augu.t. 1997 SIKKIM RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF TIBETOL06Y 6AN6TOK. SIKKIM Me-Giang: Drukpa Tshezhi 7 August 1997 Printed at Sikkim National Press, Gangtok, Sikkim Published by Director, Sikkim Research Institute of Tibetology Gangtok, Sikkim-737 102 CONT~NTS Page 1. PROMOTION OF SANSKRIT'STUDIES IN SIKKIM 5 S.K. Pathak 2. 1;.~ENDS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF BUDDHISM IS ~,Biswanath Banerjee ! 3. SOME.HUMAN ASPECTS PROMULGATED AMONG THE TiBETANS WITH REFERENCE TO ZA MA TOG BSKOD PA (KARANOA VYUHA) 19 Buddhadev Bhattacharya 4. THE CONCEPTS OF V AJRA AND ITS SYMBOLIC TRANSFORMA TION 2.5 B. Ghosh .5. a) THE JHANAS IN THE THERAVADA BUDDHISM 44 P.G. Yogi b) STHAVIRVADI BOUDHA SADHANA (HINDI) 49 P.G. Yogi 6. NOTES AND TOPICS: 67 a) ON TIBETOLOGY (Reprint B.T. No. I, 1964) Maharaj Kumar Paiden Thondup Namgyal 69 b) SANSKRIT AND TIBET AN (Reprint Himalayan Times, AprilS, 1959) 75 Maharaj Kumar Palden Thondup Namgyal c) ON BUDDHISTICS (HYBRID) SANSKRIT (Reprint B.T. N.S. No. -

The Redactions of the Adbhutadharmaparyāya from Gilgit

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Gregory Schopen Roger Jackson Indiana University Fairfield University Bloomington, Indiana, USA Fairfield, Connecticut, USA EDITORS Peter N. Gregory Ernst Steinkellner University of Illinois University of Vienna Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki University de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo,Japan Steven Collins Robert Thurman Concordia University Amherst College Montreal, Canada Amherst, Massachusetts, USA Volume 11 1988 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES The Soteriological Purpose of Nagarjuna's Philosophy: A Study of Chapter Twenty-Three of the Mula-madhyamaka-kdrikds, by William L. Ames 7 The Redactions ofthe Adbhutadharmaparydya from Gilgit, by Yael Bentor 21 Vacuite et corps actualise: Le probleme de la presence des "Personnages V6nereY' dans leurs images selon la tradition du bouddhismejaponais, by Bernard Frank 51 Ch'an Commentaries on the Heart Sutra: Preliminary Inferences on the Permutation of Chinese Buddhism, by John R. McRae 85 II. BOOK REVIEWS 1. An Introduction to Buddhism, by Jikido Takasaki (Fernando Tola and Carmen Dragonetti) 115 2. On Being Mindless: Buddhist Meditation and the Mind-Body Problem, by Paul J. Griffiths (Frank Hoffman) 116 3. The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism, by Roderick S. Bucknell and Martin Stuart-Fox (Roger Jackson) 123 OBITUARY 131 LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS 136 The Redactions of the Adbhutadharmaparydya from Gilgit* by Yael Bentor L Introduction The importance of the Gilgit collection of Sanskrit Buddhist manuscripts has long been recognized. It provides us with Sanskrit manuscripts of texts which were either previously un known in their original language or were known only through much later manuscripts which have been found in Nepal, Tibet and Japan.1 The present work includes an edition of the Ad bhutadharmaparydya (Ad), a text which falls into the former cate gory, based on three Sanskrit manuscripts from Gilgit. -

Songs on the Road: Wandering Religious Poets in India, Tibet, and Japan

6. Buddhist Surrealists in Bengal Per Kværne Abstract Towards the end of the first millennium CE, Buddhism in Bengal was dominated by the Tantric movement, characterized by an external/physical as well as internal/meditational yoga, believed to lead to spiritual enlightenment and liberation from the round of birth and death. This technique and its underlying philosophy were expressed in the Caryāgīti, a collection of short songs in Old Bengali composed by a category of poets and practitioners of yoga, some of whom apparently had a peripatetic lifestyle. One of the peculiarities of Old Bengali is the presence of a large number of homonyms, permitting play on ambiguous images. This, it is argued in the first part of the chapter, is the key to understanding many songs that are seemingly meaningless or nonsensical, or that could be superficially taken to be simply descriptions of everyday life in the countryside of Bengal. By means of their very form, the songs convey the idea of the identity of the secular and the spiri- tual, of time and eternity. The second part of the chapter makes a leap in time, space, and culture, by suggesting a resonance for the Caryāgīti in the Surrealist Movement of Western art. I Having milked the tortoise the basket cannot hold – How to cite this book chapter: Kværne, P. 2021. Buddhist Surrealists in Bengal. In: Larsson, S. and af Edholm, K. (eds.) Songs on the Road: Wandering Religious Poets in India, Tibet, and Japan. Pp. 113–126. Stockholm: Stockholm University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16993/bbi.f. -

Reading the Early Biography of the Tibetan Queen Yeshe Tsogyal

Literature and the Moral Life: Reading the Early Biography of the Tibetan Queen Yeshe Tsogyal The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Angowski, Elizabeth. 2019. Literature and the Moral Life: Reading the Early Biography of the Tibetan Queen Yeshe Tsogyal. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029522 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Literature and the Moral Life: Reading the Early Biography of the Tibetan Queen Yeshe Tsogyal A dissertation presented by Elizabeth J. Angowski to The Committee on the Study of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of The Study of Religion Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 24, 2019 © 2019 Elizabeth J. Angowski All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Janet Gyatso Elizabeth J. Angowski Literature and the Moral Life: Reading the Early Biography of the Tibetan Queen Yeshe Tsogyal ABSTRACT In two parts, this dissertation offers a study and readings of the Life Story of Yeshé Tsogyal, a fourteenth-century hagiography of an eighth-century woman regarded as the matron saint of Tibet. Focusing on Yeshé Tsogyal's figurations in historiographical and hagiographical literature, I situate my study of this work, likely the earliest full-length version of her life story, amid ongoing questions in the study of religion about how scholars might best view and analyze works of literature like biographies, especially when historicizing the religious figure at the center of an account proves difficult at best.