Population and Society in Contemporary Tibet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule

TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A COMPILATION OF REFUGEE STATEMENTS 1958-1975 A SERIES OF “EXPERT ON TIBET” PROGRAMS ON RADIO FREE ASIA TIBETAN SERVICE BY WARREN W. SMITH 1 TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A Compilation of Refugee Statements 1958-1975 Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule is a collection of twenty-seven Tibetan refugee statements published by the Information and Publicity Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1976. At that time Tibet was closed to the outside world and Chinese propaganda was mostly unchallenged in portraying Tibet as having abolished the former system of feudal serfdom and having achieved democratic reforms and socialist transformation as well as self-rule within the Tibet Autonomous Region. Tibetans were portrayed as happy with the results of their liberation by the Chinese Communist Party and satisfied with their lives under Chinese rule. The contrary accounts of the few Tibetan refugees who managed to escape at that time were generally dismissed as most likely exaggerated due to an assumed bias and their extreme contrast with the version of reality presented by the Chinese and their Tibetan spokespersons. The publication of these very credible Tibetan refugee statements challenged the Chinese version of reality within Tibet and began the shift in international opinion away from the claims of Chinese propaganda and toward the facts as revealed by Tibetan eyewitnesses. As such, the publication of this collection of refugee accounts was an important event in the history of Tibetan exile politics and the international perception of the Tibet issue. The following is a short synopsis of the accounts. -

Tibet Brief October 2020 a Report of the International Campaign for Tibet

TIBET BRIEF OCTOBER 2020 A REPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL CAMPAIGN FOR TIBET NEW REPORT REVEALS COERCIVE LABOR PROGRAM IN TIBET IN THIS ISSUE 1 New report reveals coercive labor program in Tibet 2 Tibet raised at EU-China leaders’ virtual meeting 3 China elected to UN Human Rights Council but suffers another setback as criticism grows 4 ICT joins Global Day of Action against human Military-style training of “rural surplus laborers” in the Chamdo region of Tibet in 2016. (Photo: Tibet’s Chamdo, 30 June 2016). rights violations in China 5 Seventh Tibet Work Forum MIRRORING A PROGRAM OF FORCED LABOR IN XINJIANG, BEIJING IS promises more repression PUSHING GROWING NUMBERS OF TIBETANS INTO MILITARY-STYLE "TRAINING CENTERS", WHERE THEY ARE BEING TURNED INTO LOW- 6 Arrest of New York police PAID FACTORY WORKERS, A NEW REPORT HAS FOUND. officer accused of spying The report, released on 22 September of the TAR last year, includes a number for China reveals China’s by the Jamestown Foundation and of racist assumptions about Tibetans’ efforts against Tibetans corroborated by Reuters, documents “backwardness” and the need to reform their abroad a large-scale program in the Tibet thinking and cultural identity while making New ICT report exposes Autonomous Region (TAR) that pushed them loyal to the Chinese Communist 7 more than half a million rural Tibetans off Party. It also seeks to reduce the influence fraudulent “anti-gang” trial their land and into military-style training of Tibetans’ Buddhist religion, and to force of “Sangchu 10” Tibetans centers in the first seven months of this Tibetans to abandon their traditional way of Political Prisoner Focus year alone. -

White Paper on Tibetan Culture

http://english.people.com.cn/features/tibetpaper/tibeta.html White Paper on Tibetan Culture Following is the full text of the white paper on "The Development of Tibetan Culture" released by the Information Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China June 22: Foreword I. The Spoken and Written Tibetan Language Is Widely Studied and Used, and Being Developed II. Cultural Relics and Ancient Books and Records Are Well Preserved and Utilized III. Folk Customs and Freedom of Religious Belief Are Respected and Protected IV. Culture and Art Are Being Inherited and Developed in an All- Round Way V. Tibetan Studies Are Flourishing, and Tibetan Medicine and Pharmacology Have Taken On a New Lease of Life VI. Popular Education Makes a Historic Leap VII. The News and Publishing, Broadcasting, Film and Television Industries Are Developing Rapidly Conclusion Foreword China is a united multi-ethnic country. As a member of the big family of the Chinese nation, the Tibetan people have created and developed their brilliant and distinctive culture during a long history of continuous exchanges and contacts with other ethnic groups, all of whom have assimilated and promoted each other's cultures. Tibetan culture has all along been a dazzling pearl in the treasure- house of Chinese culture as well as that of the world as a whole. The gradual merger of the Tubo culture of the Yalong Valley in the middle part of the basin of the Yarlung Zangbo River, and the ancient Shang-Shung culture of the western part of the Qinghai- Tibet Plateau formed the native Tibetan culture. -

From Tibet Confidentially

FROM TIBET CONFIDENTIALLY Secret correspondence of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama to Agvan Dorzhiev, 1911-1925 Introduction, translation, and comments by Jampa Samten and Nikolay Tsyrempilov LIBRARY OF TIBETAN WORKS & ARCHIVES Copyright © 2011 Jampa Samten and Nikolay Tsyrempilov First print: 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-93-80359-49-6 Published by the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala, H.P. 176215, and printed at Indraprastha Press (CBT), Nehru House, New Delhi-110002 To knowledgeable Tsenshap Khenché Lozang Ngawang (Agvan Dorzhiev) Acknowledgement V We gratefully acknowledge the National Museum of Buriatia that kindly permitted us to copy, research, and publish in this book the valuable materials they have preserved. Our special thanks is to former Director of the Museum Tsyrenkhanda Ochirova for it was she who first drew our attention to these letters and made it possible to bring them to light. We thank Ven. Geshe Ngawang Samten and Prof. Boris Bazarov, great enthusiasts of collaboration between Buriat and Tibetan scholars of which this book is not first result. We are grateful to all those who helped us in our work on reading and translation of the letters: Ven. Beri Jigmé Wangyel for his valuable consultations and the staff of the Central University of Tibetan Studies Ven. Ngawang Tenpel, Tashi Tsering, Ven. Lhakpa Tsering for assistance in reading and interpretation of the texts. We express our particular gratitude to Tashi Tsering (Director of Amnye Machen Institute, Tibetan Centre for Advanced Studies, Dharamsala) for his valuable assistance in identification of the persons on the Tibetan delegation group photo published in this book. -

Bulletin of Tibetology

Bulletin of Tibetology VOLUME 45 NO. 1 2009 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK, SIKKIM The Bulletin of Tibetology seeks to serve the specialist as well as the general reader with an interest in the field of study. The motif portraying the Stupa on the mountains suggests the dimensions of the field. Bulletin of Tibetology VOLUME 45 NO. 1 2009 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK, SIKKIM Patron HIS EXCELLENCY SHRI BALMIKI PRASAD SINGH, THE GOVERNOR OF SIKKIM Advisor TASHI DENSAPA, DIRECTOR NIT Editorial Board FRANZ-KARL EHRHARD ACHARYA SAMTEN GYATSO SAUL MULLARD BRIGITTE STEINMANN TASHI TSERING MARK TURIN ROBERTO VITALI Editor ANNA BALIKCI-DENJONGPA Guest Editor for Present Issue DANIEL A. HIRSHBERG Assistant Editors TSULTSEM GYATSO ACHARYA THUPTEN TENZING The Bulletin of Tibetology is published bi-annually by the Director, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok, Sikkim. Annual subscription rates: South Asia, Rs150. Overseas, $20. Correspondence concerning bulletin subscriptions, changes of address, missing issues etc., to: Administrative Assistant, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok 737102, Sikkim, India ([email protected]). Editorial correspondence should be sent to the Editor at the same address. Submission guidelines. We welcome submission of articles on any subject of the history, language, art, culture and religion of the people of the Tibetan cultural area although we would particularly welcome articles focusing on Sikkim, Bhutan and the Eastern Himalayas. Articles should be in English or Tibetan, submitted by email or on CD along with a hard copy and should not exceed 5000 words in length. The views expressed in the Bulletin of Tibetology are those of the contributors alone and not the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology. -

Tibet Was Never Part of China Before 1950: Examples of Authoritative Pre-1949 Chinese Documents That Prove It

Article Tibet was Never Part of China Before 1950: Examples of Authoritative pre-1949 Chinese Documents that Prove It Hon-Shiang LAU Abstract The claim ‘Tibet has been part of China since antiquity’ is crucial for the PRC to legitimize her annexation of Tibet in 1950. However, the vast amount of China’s pre-1949 primary-source records consistently indicate that this claim is false. This paper presents a very small sample of these records from the Ming and the Qing dynasties to illustrate how they unequivocally contradict PRC’s claim. he People’s Republic of China (PRC) claims that ‘Tibet has been part of China T since antiquity西藏自古以来就是中国的一部分.’ The Central Tibet Administration (CTA), based in Dharamshala in India, refuses to accede to this claim, and this refusal by the CTA is used by the PRC as: 1. A prima facie proof of CTA’s betrayal to her motherland (i.e., China), and 2. Justification for not negotiating with the CTA or the Dalai Lama. Why must the PRC’s insist that ‘Tibet has been part of China since antiquity’? China is a signatory to the 1918 League-of-Nations Covenants and the 1945 United- Nations Charter; both documents prohibit future (i.e., post-1918) territorial acquisitions via conquest. Moreover, the PRC incessantly paints a sorry picture of Prof. Hon-Shiang LAU is an eminent Chinese scholar and was Chair Professor at the City University of Hong Kong. He retired in 2011 and has since then pursued research on Chinese government records and practices. His study of Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, and Manchu period official records show that Tibet was never treated as part of China. -

Report on Tibetan Herder Relocation Programs

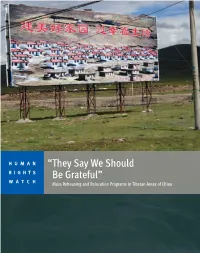

HUMAN “They Say We Should RIGHTS Be Grateful” WATCH Mass Rehousing and Relocation Programs in Tibetan Areas of China “They Say We Should Be Grateful” Mass Rehousing and Relocation Programs in Tibetan Areas of China Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0336 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2013 ISBN: 978-1-62313-0336 “They Say We Should Be Grateful” Mass Rehousing and Relocation Programs in Tibetan Areas of China Map: Tibetan Autonomous Areas within the People’s Republic of China ............................... i Glossary ............................................................................................................................ -

Xikang: Han Chinese in Sichuan's Western Frontier

XIKANG: HAN CHINESE IN SICHUAN’S WESTERN FRONTIER, 1905-1949. by Joe Lawson A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Victoria University of Wellington 2011 Abstract This thesis is about Han Chinese engagement with the ethnically diverse highlands west and south-west of the Sichuan basin in the first half of the twentieth century. This territory, which includes much of the Tibetan Kham region as well as the mostly Yi- and Han-settled Liangshan, constituted Xikang province between 1939 and 1955. The thesis begins with an analysis of the settlement policy of the late Qing governor Zhao Erfeng, as well as the key sources of influence on it. Han authority suffered setbacks in the late 1910s, but recovered from the mid-1920s under the leadership of General Liu Wenhui, and the thesis highlights areas of similarity and difference between the Zhao and Liu periods. Although contemporaries and later historians have often dismissed the attempts to build Han Chinese- dominated local governments in the highlands as failures, this endeavour was relatively successful in a limited number of places. Such success, however, did not entail the incorporation of territory into an undifferentiated Chinese whole. Throughout the highlands, pre-twentieth century local institutions, such as the wula corvée labour tax in Kham, continued to exercise a powerful influence on the development and nature of local and regional government. The thesis also considers the long-term life (and death) of ideas regarding social transformation as developed by leaders and historians of the highlands. -

THE ROOTED STATE: PLANTS and POWER in the MAKING of MODERN CHINA's XIKANG PROVINCE by MARK E. FRANK DISSERTATION Submitted In

THE ROOTED STATE: PLANTS AND POWER IN THE MAKING OF MODERN CHINA’S XIKANG PROVINCE BY MARK E. FRANK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in East Asian Languages and Cultures in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Dan Shao, Chair Associate Professor Robert Morrissey Assistant Professor Roderick Wilson Associate Professor Laura Hostetler, University of Illinois Chicago Abstract This dissertation takes the relationship between agricultural plants and power as its primary lens on the history of Chinese state-building in the Kham region of eastern Tibet during the early twentieth century. Farming was central to the way nationalist discourse constructed the imagined community of the Chinese nation, and it was simultaneously a material practice by which settlers reconfigured the biotic community of soils, plants, animals, and human beings along the frontier. This dissertation shows that Kham’s turbulent absorption into the Chinese nation-state was shaped by a perpetual feedback loop between the Han political imagination and the grounded experiences of soldiers and settlers with the ecology of eastern Tibet. Neither expressions of state power nor of indigenous resistance to the state operated neatly within the human landscape. Instead, the rongku—or “flourishing and withering”—of the state was the product of an ecosystem. This study chronicles Chinese state-building in Kham from Zhao Erfeng’s conquest of the region that began in 1905 until the arrival of the People’s Liberation Army in 1950. Qing officials hatched a plan to convert Kham into a new “Xikang Province” in the last years of the empire, and officials in the Republic of China finally realized that goal in 1939. -

Bulletin of Tibetology Seeks to Serve the Specialist As Welt As the General Reader with an Inter Est in This Field of Study

Bulletin of Tilbettology ~ NEW SERIES 1997 No.2 7 Augu.t" 1997 filKKIM REliEARI:H INBTITUft OF TIBETOLD&Y .&AN&TaI( ••IKIUM The Bulletin of Tibetology seeks to serve the specialist as welt as the general reader with an inter est in this field of study. The motif portraying the stupa on the mountain suggests the dimensions of the field. EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor Tashi Tobden I.A.S. Member Shri Bhajagovinda Ghosh Member Sonam Gyatso Dpkham Member Acharya Samten Gyatso Member Dr. Rigzin Ngodup Bulletin of Tn.lbetology NEW SERIES 1997 No.2 7 Augu.t. 1997 SIKKIM RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF TIBETOL06Y 6AN6TOK. SIKKIM Me-Giang: Drukpa Tshezhi 7 August 1997 Printed at Sikkim National Press, Gangtok, Sikkim Published by Director, Sikkim Research Institute of Tibetology Gangtok, Sikkim-737 102 CONT~NTS Page 1. PROMOTION OF SANSKRIT'STUDIES IN SIKKIM 5 S.K. Pathak 2. 1;.~ENDS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF BUDDHISM IS ~,Biswanath Banerjee ! 3. SOME.HUMAN ASPECTS PROMULGATED AMONG THE TiBETANS WITH REFERENCE TO ZA MA TOG BSKOD PA (KARANOA VYUHA) 19 Buddhadev Bhattacharya 4. THE CONCEPTS OF V AJRA AND ITS SYMBOLIC TRANSFORMA TION 2.5 B. Ghosh .5. a) THE JHANAS IN THE THERAVADA BUDDHISM 44 P.G. Yogi b) STHAVIRVADI BOUDHA SADHANA (HINDI) 49 P.G. Yogi 6. NOTES AND TOPICS: 67 a) ON TIBETOLOGY (Reprint B.T. No. I, 1964) Maharaj Kumar Paiden Thondup Namgyal 69 b) SANSKRIT AND TIBET AN (Reprint Himalayan Times, AprilS, 1959) 75 Maharaj Kumar Palden Thondup Namgyal c) ON BUDDHISTICS (HYBRID) SANSKRIT (Reprint B.T. N.S. No. -

Download Article

International Conference on Economics, Social Science, Arts, Education and Management Engineering (ESSAEME 2015) Comparative Study on Indoor Thermal Environment in Winter of Two Tibetan Dwellings SUOLANG Baimu1,a, HE Quan2,b and LIU Jiaping3,c 1Tibet University, Lhasa ,China 2 Xi'an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an 710055, China 3Xi'an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an 710055, China [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: Tibetan dwelling; indoor thermal environment; solar energy use; winter thermal environment Abstract. Traditional Tibetan dwelling is a unique building style formed in the plateau environment. Due to technical and economic limits, traditional Tibetan dwellings perform insufficiently to face the high comfort requirements of contemporary life under cold climate. In this paper, we selected two typical dwellings, located in Chamdo Region and Kangding County respectively, to carry out the indoor thermal environment measurement in winter, and to optimize the design methods of residential houses. The results of this comparative studu shows that under similar conditions of solar radiation, the indoor thermal environment is better in Kangding residential house is. The differences in building layout, envelope material and solar energy usage are the primary reasons for this phenomenon. Introduction Tibetan plateau, with its fragile ecological environment, is regarded as one of the world’s harshest living environment. In the long history of Tibet, the local residents have built traditional dwellings with limited materials and technologies coping extreme climates . Extremely low ecological cost was used to meet the basic survival and multiplied needs of Tibetan in snowy plateau. However, these traditional local living conditions are not comfortable with today’s building standards. -

Course Structure of Ma in Buddhism and Tibetan Studies, Namgyal

COURSE STRUCTURE OF M.A. IN BUDDHISM AND TIBETAN STUDIES, NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY, GANGTOK The Sikkim University follows the credit system for its Master‟s Degree Program. MA programme consists of total 64 credits during the span of four semesters of which 4 credits are allocated for dissertations and viva voce. However, the students will not be allowed to earn more than 16 credits in a semester. Student has to attend minimum 75 % classes in each and every course. The Master‟s Program in Buddhism and Tibetan studies has the following major components: Compulsory courses, Elective courses and one Dissertation. Scheme of Study: In order to enable the student to complete Master‟s Program within the minimum period of two years (or four semesters), a student is allowed to take 64 credits worth of courses (or 16 credits each semester). There are compulsory courses in the first and second semesters. In third semester, student has to opt two core courses (of which one is research methodology) and choose any 2 elective courses while in semester fourth, students has to opt one core course, choose any two elective courses and submit one dissertation (followed by viva voce) which is also core course. Evaluation: Each paper is of 100 marks of which 50 marks allocated for mid semester or internal assessment (sessionals, term papers, book reviews, articles review, case studies, class tests, research proposal etc.) conducted by the concerned course teacher and end semester consists of 50 marks. Semester-wise Scheme of Study: Compulsory Elective Total Total Total Year of Study Courses Courses courses Credits Marks Semester – I 4 Nil 4 16 400 Semester – II 4 Nil 4 16 400 Semester – IIII 2 2 4 16 400 Semester – IV 2 2 4 16 400 Total (two years) 12 4 16 64 1600 Structure of Codified and Unitised MA Syllabus of the Department of Buddhist and Tibetan Studies, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok is presented as follows: Core/ Code Course Credits Marks Elective M.A.