The Colonization of Texas: 1820-1830

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lone Star State

Texas: The Lone Star State By Cynthia A. Malecki "Texas, Our Texas! All hail the mighty State! Texas, Our Texas! So wonderful, so great! Boldest and grandest, withstanding ev'ry test, Empire wide and glorious, you stand supremely blest." 1st stanza of the Texas state song They say that everything is big in Texas–big farms, big ranches, big cities, big money, and even big hair. Texas is the biggest of the 48 contiguous U.S. states, with 267,277 square miles (692,244 square km), which is bigger than the 14 smallest states combined.(1) It is approximately 850 miles (1,370 km) from north to south and from west to east. The biggest ranch in Texas is The King Ranch in Kingsville, which is larger than the state of Rhode Island. The cities of Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio are among the nation's ten largest. The Port of Houston handles more foreign cargo than any other U.S. port. Texas is the second largest producer of electronic components in the U.S. and the nation's second leading exporter. Worldwide television viewers might remember the TV show "Dallas" featuring the Ewing family who lived on the South Fork Ranch in Dallas, Texas. Weekly shows featured the extravagant lifestyle of oil barons and their wives with big hair. (Usually found in the southern United States, big hair is the result of combing the hair and spraying it to produce a hairstyle puffed up two or three times its normal volume and capable of withstanding even the strongest winds.) Former Texas governor Ann Richards even declared an official Texas Big Hair Day in 1993. -

Stephen F. Austin and the Empresarios

169 11/18/02 9:24 AM Page 174 Stephen F. Austin Why It Matters Now 2 Stephen F. Austin’s colony laid the foundation for thousands of people and the Empresarios to later move to Texas. TERMS & NAMES OBJECTIVES MAIN IDEA Moses Austin, petition, 1. Identify the contributions of Moses Anglo American colonization of Stephen F. Austin, Austin to the colonization of Texas. Texas began when Stephen F. Austin land title, San Felipe de 2. Identify the contributions of Stephen F. was given permission to establish Austin, Green DeWitt Austin to the colonization of Texas. a colony of 300 American families 3. Explain the major change that took on Texas soil. Soon other colonists place in Texas during 1821. followed Austin’s lead, and Texas’s population expanded rapidly. WHAT Would You Do? Stephen F. Austin gave up his home and his career to fulfill Write your response his father’s dream of establishing a colony in Texas. to Interact with History Imagine that a loved one has asked you to leave in your Texas Notebook. your current life behind to go to a foreign country to carry out his or her wishes. Would you drop everything and leave, Stephen F. Austin’s hatchet or would you try to talk the person into staying here? Moses Austin Begins Colonization in Texas Moses Austin was born in Connecticut in 1761. During his business dealings, he developed a keen interest in lead mining. After learning of George Morgan’s colony in what is now Missouri, Austin moved there to operate a lead mine. -

The Development of Free Public Schools in Texas. 41P

DOCUMOIT RESUME 4D 126 615 BA 008 558 AUTHOR Holleman, I. Thomas, Jr. TITLE The Development of Free Public Schools inTexas. PUB DATE [13] NOTE 41p.; Not available in hard copy due to marginal legibility of original document EDRS PRICE NF-S0.83 Plus Postage. BC Not Available fromEDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Educational Finance; *Educational History; Elementary Secondary Education; Historical Reviews; Property Taxes; *Public Education; public School Systems; School Funds; State Aid; State Boards of Education; *State Government; *State Legislation; State School District Relationship , IDENTIFIERS *Texas ABSTRACT This paper summarizes the historical foundationsfor the financing and maintenance of Texas'present day school system. This review traces the'history ofTexas public education from the seventeenth century through 1949 when threemajor s9fOol reorganization laws were enacted by thestate legiilature.'The earliest schools in Texaswere associated with the Spanish missions and were-intended to educate (and control)'the Indians. Education suffered under the Mexican regime, which failedto provide fonds for schools. The Republic of Texas setup a public school system based on: land grants to counties. This funding approachwas later employed when Texas entered the Union, and continued untilthe Civil War brought havoc to public education. However, afterReconstruction, the ( 1875 state constitution provided fora perpetual school fund based on property and poll taxes as wellas for a state board of education. Independent school districts emerged. Finally in1949, the state legislature mandated that 12years of schooling for all children are mandatory and gave the state board of educationHmorepdwer. (DS) *******41414141************************41414141**4141414141***444141*****************- Documents Acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * * materials not available from othersources. -

Commencement Program Baylor University School of Law

Saturday, July 31 Two Thousand Twenty One Ten O’Clock in the Morning First Baptist Church of Waco Waco, Texas Commencement Program Baylor University School of Law Saturday, July 31, 2021 — Ten O’Clock in the Morning First Baptist Church of Waco Waco, Texas Processional Significance of the Juris Doctor Regalia Emily Monk Leah W. Teague Cellist Associate Dean and Professor of Law Master of Music Student, Baylor University School of Music Presentation of Class Dean Toben Welcome Bradley J.B. Toben Degree Conferral Dean and M.C. & Dr. Brickhouse Mattie Caston Chair of Law Presentation of Diplomas Invocation Dr. Brickhouse James Donnell Wilson Member of the Commencement Class Dean Toben Associate Dean Teague Introductions Dean Toben Angela Cruseturner Assistant Dean of Career Development Student Remarks Hooding of Graduates Matthew James McKinnon Highest Ranking Student Jeremy Counseller in the Commencement Class Professor of Law James E. Wren Address Leon Jaworski Chair of Gerald R. Powell Practice & Procedure Master Teacher and Abner V. McCall Professor of Evidence Recessional Ms. Monk Remarks Nancy Brickhouse, Ph.D. Provost, Baylor University JURIS DOCTOR DEGREES Conferred July 31, 2021 Garrett S. Anderson Steven Ovando Kimberly Taise Andrade Preston Roquemore Polk Emily Jean Carria Audrey Michelle Ramirez Christian Louis Carson-Banister Emma Lee Roddy Madelyn Grace Caskey David Anthony-Cruz Rothweil Samantha Landi Chaiken Ryan William Rowley Jessica L. Francis Jennifer Margaux Schein Byron A. Haney Alexandra Irene Simms Sydney Anne Ironside Pawandeep Singh William Vascoe Jordan IV Tara Smith Hambacher McKellar Lee Karr Danielle Brogan Snow Matthew Austin Katona Nicholas Todd Stevens Alyssa Morgan Killin David W. -

Stumpf (Ella Ketcham Daggett) Papers, 1866, 1914-1992

Texas A&M University-San Antonio Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection Archives & Special Collections 2020 Stumpf (Ella Ketcham Daggett) Papers, 1866, 1914-1992 DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/findingaids Recommended Citation DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio, "Stumpf (Ella Ketcham Daggett) Papers, 1866, 1914-1992" (2020). Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection. 160. https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/findingaids/160 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ella Ketcham Daggett Stumpf Papers, 1866, 1914-1992 Descriptive Summary Creator: Stumpf, Ella Ketcham Daggett (1903-1993) Title: Ella Ketcham Daggett Stumpf Papers, 1866-1914-1992 Dates: 1866, 1914-1992 Creator Ella Ketcham Daggett was an active historic preservationist and writer Abstract: of various subjects, mainly Texas history and culture. Content Consisting primarily of short manuscripts and the source material Abstract: gathered in their production, the Ella Ketcham Daggett Stumpf Papers include information on a range of topics associated with Texas history and culture. Identification: Col 6744 Extent: 16 document and photograph boxes, 1 artifacts box, 2 oversize boxes, 1 oversize folder Language: Materials are in English Repository: DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Biographical Note A fifth-generation Texan, Ella Ketcham Daggett was born on October 11, 1903 at her grandmother’s home in Palestine, Texas to Fred D. -

CASTRO's COLONY: EMPRESARIO COLONIZATION in TEXAS, 1842-1865 by BOBBY WEAVER, B.A., M.A

CASTRO'S COLONY: EMPRESARIO COLONIZATION IN TEXAS, 1842-1865 by BOBBY WEAVER, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted August, 1983 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I cannot thank all those who helped me produce this work, but some individuals must be mentioned. The idea of writing about Henri Castro was first suggested to me by Dr. Seymour V. Connor in a seminar at Texas Tech University. That idea started becoming a reality when James Menke of San Antonio offered the use of his files on Castro's colony. Menke's help and advice during the research phase of the project provided insights that only years of exposure to a subject can give. Without his support I would long ago have abandoned the project. The suggestions of my doctoral committee includ- ing Dr. John Wunder, Dr. Dan Flores, Dr. Robert Hayes, Dr. Otto Nelson, and Dr. Evelyn Montgomery helped me over some of the rough spots. My chairman, Dr. Alwyn Barr, was extremely patient with my halting prose. I learned much from him and I owe him much. I hope this product justifies the support I have received from all these individuals. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii LIST OF MAPS iv INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter I. THE EMPRESARIOS OF 1842 7 II. THE PROJECT BEGINS 39 III. A TOWN IS FOUNDED 6 8 IV. THE REORGANIZATION 97 V. SETTLING THE GRANT, 1845-1847 123 VI. THE COLONISTS: ADAPTING TO A NEW LIFE ... -

Mexican American History Resources at the Briscoe Center for American History: a Bibliography

Mexican American History Resources at the Briscoe Center for American History: A Bibliography The Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin offers a wide variety of material for the study of Mexican American life, history, and culture in Texas. As with all ethnic groups, the study of Mexican Americans in Texas can be approached from many perspectives through the use of books, photographs, music, dissertations and theses, newspapers, the personal papers of individuals, and business and governmental records. This bibliography will familiarize researchers with many of the resources relating to Mexican Americans in Texas available at the Center for American History. For complete coverage in this area, the researcher should also consult the holdings of the Benson Latin American Collection, adjacent to the Center for American History. Compiled by John Wheat, 2001 Updated: 2010 2 Contents: General Works: p. 3 Spanish and Mexican Eras: p. 11 Republic and State of Texas (19th century): p. 32 Texas since 1900: p. 38 Biography / Autobiography: p. 47 Community and Regional History: p. 56 The Border: p. 71 Education: p. 83 Business, Professions, and Labor: p. 91 Politics, Suffrage, and Civil Rights: p. 112 Race Relations and Cultural Identity: p. 124 Immigration and Illegal Aliens: p. 133 Women’s History: p. 138 Folklore and Religion: p. 148 Juvenile Literature: p. 160 Music, Art, and Literature: p. 162 Language: p. 176 Spanish-language Newspapers: p. 180 Archives and Manuscripts: p. 182 Music and Sound Archives: p. 188 Photographic Archives: p. 190 Prints and Photographs Collection (PPC): p. 190 Indexes: p. -

LOTS of LAND PD Books PD Commons

PD Commons From the collection of the n ^z m PrelingerTi I a JjibraryJj San Francisco, California 2006 PD Books PD Commons LOTS OF LAND PD Books PD Commons Lotg or ^ 4 I / . FROM MATERIAL COMPILED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE COMMISSIONER OF THE GENERAL LAND OFFICE OF TEXAS BASCOM GILES WRITTEN BY CURTIS BISHOP DECORATIONS BY WARREN HUNTER The Steck Company Austin Copyright 1949 by THE STECK COMPANY, AUSTIN, TEXAS All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine or newspaper. PRINTED AND BOUND IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA PD Books PD Commons Contents \ I THE EXPLORER 1 II THE EMPRESARIO 23 Ml THE SETTLER 111 IV THE FOREIGNER 151 V THE COWBOY 201 VI THE SPECULATOR 245 . VII THE OILMAN 277 . BASCOM GILES PD Books PD Commons Pref<ace I'VE THOUGHT about this book a long time. The subject is one naturally very dear to me, for I have spent all of my adult life in the study of land history, in the interpretation of land laws, and in the direction of the state's land business. It has been a happy and interesting existence. Seldom a day has passed in these thirty years in which I have not experienced a new thrill as the files of the General Land Office revealed still another appealing incident out of the history of the Texas Public Domain. -

Changes in Spanish Texas

Warm Up The Mexican National Era Unit 5 Vocab •Immigrant - a person who comes to a country where they were not born in order to settle there •Petition - a formal message requesting something that is submitted to an authority •Tejano - a person of Mexican descent living in Texas •Militia - civilians trained as soldiers but not part of the regular army •Empresario -the Spanish word for a land agent whose job it was to bring in new settlers to an area •Anglo-American - people whose ancestors moved from one of many European countries to the United States and who now share a common culture and language •Recruit - to persuade someone to join a group •Filibuster - an adventurer who engages in private rebellious activity in a foreign country •Compromise - an agreement in which both sides give something up •Republic - a political system in which the supreme power lies in a body of citizens who can elect people to represent them •Neutral - Not belonging to one side or the other •Cede - to surrender by treaty or agreement •Land Title - legal document proving land ownership •Emigrate - leave one's country of residence for a new one Warm Up Warm-up • Why do you think that the Spanish colonists wanted to break away from Spain? 5 Unrest and Revolution Mexican Independence & Impact on Texas • Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla – Gave a speech called “Grito de Dolores” in 1810. Became known as the Father of the Mexican independence movement. • Leads rebellion but is killed in 1811. • Mexico does not win independence until 1821. Hidalgo’s Supporters Rebel Against Spain • A group of rebels led by Juan Bautista de las Casas overthrew the Spanish government in San Antonio. -

Texas on the Mexican Frontier

Texas on the Mexican Frontier Texas History Chapter 8 1. Mexican Frontier • Texas was vital to Mexico in protecting the rest of the country from Native Americans and U.S. soldiers • Texas’ location made it valuable to Mexico 2. Spanish Missions • The Spanish had created missions to teach Christianity to the American Indians • The Spanish also wanted to keep the French out of Spanish-claimed territory 3. Empresarios in Texas • Mexico created the empresario system to bring new settlers to Texas • Moses Austin received the first empresario contract to bring Anglo settlers to Texas. 4. Moses Austin Moses Austin convinced Mexican authorities to allow 300 Anglo settlers because they would improve the Mexican economy, populate the area and defend it from Indian attacks, and they would be loyal citizens. 5. Moses Austin His motivation for establishing colonies of American families in Texas was to regain his wealth after losing his money in bank failure of 1819. He met with Spanish officials in San Antonio to obtain the first empresario contract to bring Anglo settlers to Texas. 6. Other Empresarios • After Moses Austin death, his son, Stephen became an empresario bring the first Anglo-American settlers to Texas • He looked for settlers who were hard- working and law abiding and willing to convert to Catholicism and become a Mexican citizen • They did NOT have to speak Spanish 7. Other Empresarios • His original settlers, The Old Three Hundred, came from the southeastern U.S. • Austin founded San Felipe as the capital of his colony • He formed a local government and militia and served as a judge 8. -

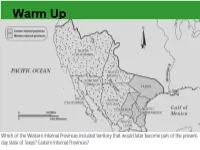

Spanish Colonial and Mexican National Content Module

Texas History Spanish Colonial and Mexican National Eras Content Module This content module has been curated using existing Law-Related Education materials along with images available for public use. This resource has been provided to assist educators with delivering the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills for middle school Texas History. This content module may be utilized as a tool to help supplement instruction. It is not intended to be a complete unit of study. Note: Arrows have been placed throughout the module to indicate areas where students should interact with the module. All rights reserved. Permission is granted for these materials to be reproduced for classroom use only. No part of these materials may be reproduced in any other form or for any other purpose without the written consent of Law Related Education, State Bar of Texas. For additional information on the LRE Program, please go to www.texaslre.org Spanish Colonial (late 1600s to early 1800s) and Mexican National (1821-1836) Era On the map below, circle Spain , Mexico, and the area we call Texas today. Source: https://lccn.loc.gov/78692118 Read the summary of this era of Texas History below and highlight or underline 3 key words that stand out and help to explain the summary. Spain gave up the search for gold during the Spanish Colonial period and turned their focus to establishing presidios and missions, as well as converting native inhabitants to Catholicism. Spain established missions throughout present-day Texas and laid claim to much of the land in Central America, and Mexico in North America. -

Independence Trail Region, Known As the “Cradle of Texas Liberty,” Comprises a 28-County Area Stretching More Than 200 Miles from San Antonio to Galveston

n the saga of Texas history, no era is more distinctive or accented by epic events than Texas’ struggle for independence and its years as a sovereign republic. During the early 1800s, Spain enacted policies to fend off the encroachment of European rivals into its New World territories west of Louisiana. I As a last-ditch defense of what’s now Texas, the Spanish Crown allowed immigrants from the U.S. to settle between the Trinity and Guadalupe rivers. The first settlers were the Old Three Hundred families who established Stephen F. Austin’s initial colony. Lured by land as cheap as four cents per acre, homesteaders came to Texas, first in a trickle, then a flood. In 1821, sovereignty shifted when Mexico won independence from Spain, but Anglo-American immigrants soon outnumbered Tejanos (Mexican-Texans). Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna seized control of Mexico in 1833 and gripped the country with ironhanded rule. By 1835, the dictator tried to stop immigration to Texas, limit settlers’ weapons, impose high tariffs and abolish slavery — changes resisted by most Texans. Texas The Independence ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ Trail ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ On March 2, 1836, after more than a year of conclaves, failed negotiations and a few armed conflicts, citizen delegates met at what’s now Washington-on-the-Brazos and declared Texas independent. They adopted a constitution and voted to raise an army under Gen. Sam Houston. TEXAS STATE LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES Gen. Sam Houston THC The San Jacinto Monument towers over the battlefield where Texas forces defeated the Mexican Army. TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Four days later, the Alamo fell to Santa Anna.