Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Context Statement City of Benicia February 2011 Benicia, CA

Historic Context Statement City of Benicia February 2011 Benicia, CA Prepared for City of Benicia Department of Public Works & Community Development Prepared by page & turnbull, inc. 1000 Sansome Street, Ste. 200, San Francisco CA 94111 415.362.5154 / www.page-turnbull.com Benicia Historic Context Statement FOREWORD “Benicia is a very pretty place; the situation is well chosen, the land gradually sloping back from the water, with ample space for the spread of the town. The anchorage is excellent, vessels of the largest size being able to tie so near shore as to land goods without lightering. The back country, including the Napa and Sonoma Valleys, is one of the finest agriculture districts in California. Notwithstanding these advantages, Benicia must always remain inferior in commercial advantages, both to San Francisco and Sacramento City.”1 So wrote Bayard Taylor in 1850, less than three years after Benicia’s founding, and another three years before the city would—at least briefly—serve as the capital of California. In the century that followed, Taylor’s assessment was echoed by many authors—that although Benicia had all the ingredients for a great metropolis, it was destined to remain in the shadow of others. Yet these assessments only tell a half truth. While Benicia never became the great commercial center envisioned by its founders, its role in Northern California history is nevertheless one that far outstrips the scale of its geography or the number of its citizens. Benicia gave rise to the first large industrial works in California, hosted the largest train ferries ever constructed, and housed the West Coast’s primary ordnance facility for over 100 years. -

Ships!), Maps, Lighthouses

Price £2.00 (free to regular customers) 03.03.21 List up-dated Winter 2020 S H I P S V E S S E L S A N D M A R I N E A R C H I T E C T U R E 03.03.20 Update PHILATELIC SUPPLIES (M.B.O'Neill) 359 Norton Way South Letchworth Garden City HERTS ENGLAND SG6 1SZ (Telephone; 01462-684191 during my office hours 9.15-3.15pm Mon.-Fri.) Web-site: www.philatelicsupplies.co.uk email: [email protected] TERMS OF BUSINESS: & Notes on these lists: (Please read before ordering). 1). All stamps are unmounted mint unless specified otherwise. Prices in Sterling Pounds we aim to be HALF-CATALOGUE PRICE OR UNDER 2). Lists are updated about every 12-14 weeks to include most recent stock movements and New Issues; they are therefore reasonably accurate stockwise 100% pricewise. This reduces the need for "credit notes" and refunds. Alternatives may be listed in case some items are out of stock. However, these popular lists are still best used as soon as possible. Next listings will be printed in 4, 8 & 12 months time so please indicate when next we should send a list on your order form. 3). New Issues Services can be provided if you wish to keep your collection up to date on a Standing Order basis. Details & forms on request. Regret we do not run an on approval service. 4). All orders on our order forms are attended to by return of post. We will keep a photocopy it and return your annotated original. -

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan A Comprehensive Listing of the Vessels Built from Schooners to Steamers from 1810 to the Present Written and Compiled by: Matthew J. Weisman and Paula Shorf National Museum of the Great Lakes 1701 Front Street, Toledo, Ohio 43605 Welcome, The Great Lakes are not only the most important natural resource in the world, they represent thousands of years of history. The lakes have dramatically impacted the social, economic and political history of the North American continent. The National Museum of the Great Lakes tells the incredible story of our Great Lakes through over 300 genuine artifacts, a number of powerful audiovisual displays and 40 hands-on interactive exhibits including the Col. James M. Schoonmaker Museum Ship. The tales told here span hundreds of years, from the fur traders in the 1600s to the Underground Railroad operators in the 1800s, the rum runners in the 1900s, to the sailors on the thousand-footers sailing today. The theme of the Great Lakes as a Powerful Force runs through all of these stories and will create a lifelong interest in all who visit from 5 – 95 years old. Toledo and the surrounding area are full of early American History and great places to visit. The Battle of Fallen Timbers, the War of 1812, Fort Meigs and the early shipbuilding cities of Perrysburg and Maumee promise to please those who have an interest in local history. A visit to the world-class Toledo Art Museum, the fine dining along the river, with brew pubs and the world famous Tony Packo’s restaurant, will make for a great visit. -

Instructions for Recording Historical Resources

INSTRUCTIONS FOR RECORDING HISTORICAL RESOURCES Office of Historic Preservation P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 942196-0001 March 1995 This publication has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, nor does mention of any trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation. PREFACE This manual is the result of many hours of effort by a diverse consortium of preservation professionals and other interested persons. The effort was coordinated by the California Department of Transportation through an agreement with the California Office of Historic Preservation. The goals of the effort were to: · Facilitate the integration of the Historic Resources Inventory and the California Archaeological Inventory; · Encourage the collection of information about all types of historical resources; · Permit more flexibility in the way information is collected; and · Improve access to information about historical resources. This manual builds on the knowledge and practical experience gained from the development and use of the Handbook for Completing an Archaeological Site Record (Office of Historic Preservation 1989b) and the Instructions for Completing the California Historic Resources Inventory Form (Office of Historic Preservation 1990). The procedures and forms described in this manual are designed to eventually supersede both existing manuals and their respective recording forms (DPR 422 and 523). The new forms in this manual have been assigned temporary designations within the DPR 523 series. -

The Magnetic Survey of the North Pacific Ocean: Instruments, Methods, and Preliminary Results

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ZENODO and vouu .JUNE, 9o6 THE MAGNETIC SURVEY OF THE NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN: INSTRUMENTS, METHODS, AND PRELIMINARY RESULTS. • BY L. A. BAUER, Director. NEED o• OCEaNiC SurvEYS. As is %vellknown, the CarnegieInstitution of Washington authorized its Departmentof Terrestrial Magnetismto undertake a magneticsurvey of the North PacificOcean, and madea pro- visional allotment of $2o,ooo to cover the initial costs of its inau- guration and progressduring the year x9o5,in accordancewith a plan submitted by Messrs. L.A. Bauer and O. W. Littlehales.'-' [The allotmentfor x9o6has beensufficiently enlarged to permit the continuousand uninterrupted prosecutionof the work, and ample assurancehas been received of similar allotments, so that the systematic magnetic survey of the oceanic areas,not alone of the North PacificOcean, is now an assuredfact.] A single quotationwill sufficeto show that there were good groundsfor the undertaking of an oceanicmagnetic survey, and for beginningfirst of all with the Ocean,so rapidlydeveloping in commercial importance--the North Pacific Ocean. ProfessorArthur Schuster states as his opinion' "I believe that no material progressof terrestrial magnetismis possibleuntil the magneticconstants of the great ocean basins,especially the Pacific, have been determined more accuratelythan they are at •Summaryof two addressesbefore the PhilosophicalSociety of Washington, (October,•9o5, and April, z9o6),and beforethe AmericanPhysical Society (in Octo- ber, •9o5), with additions to date. •See Terr. 3fag., Vol. IX, p. •63. x 65 66 L..4. B.4 f_/œR [vo•..x•, No.2.] present. There is reasonto believethat theseconstants may be afi['ectedby considerablesystematic errors. -

Camel Tracks

CAMEL TRACKS Year 2011 Phone (707)745-5435 email: [email protected] website: beniciahistoricalmuseum.org Nov. / Dec. BOARD OF DIRECTORS The mission of the Benicia Historical Museum is to engage the community in the Museum Docents James Lessenger, M.D. evolving history of Benicia and the Arsenal and their influence in the development of our ♦ country. Louis Alfeld President The Museum complex is the center where history is seen, enjoyed and preserved. ♦ Toni Haughey Through exhibits, events and educational programs we enlighten the public about the Tania Borostyan Vice President history of this unique city. ♦ Karen Burns Mary Marino Revised and adopted 2006 ♦ Secretary Robert Cates Ian Toner ♦ Sonny Flores Treasurer ♦ Louis Alfeld David Galligan ♦ Treasurer Assistant Kimble Goodman John Halliday ♦ Toni Haughey Larry Lauber ♦ Carol Scott Jim Lessenger ♦ Bill Scott Mary Marino Susan Sullivan ♦ Lori Morris Jim Trimble ♦ Bill Warren Leonide McKay ♦ MUSEUM STAFF Lorraine Patten ♦ Elizabeth d’Huart Bob Rozett Executive Director ♦ Tania Borostyan Eric Sargeson Office Manager ♦ Jessica Sargeson Charles Pregeant Complex Caretaker ♦ Carol Scott VOLUNTEER STAFF ♦ Bill Scott Harry Wassmann ♦ Curator Emeritus Susan Sullivan ♦ Beverly Phelan Sharon Toner Curator ♦ Bill Venturelli Roberta Garrett Registrar We are always looking for Bob Kvasnicka new docents. Please contact the Museum to learn about Registrar the docent training schedule Jim Garrett and the benefits accrued to docent members and Multitask Volunteer nonmembers. Lorraine Patten We are always exited to Museum Educator work with high school and Toni Haughey college students to help build their applications Gift shop manager Come buy your Christmas tree at our Tree Lot for institutions of higher Lou Alfeld learning and future and support your Museum and Genesis House. -

Nominating Historic Vessels and Shipwrecks to the National Register of Historic Places James P

..-----m]1 1-------- Technical information on comprehensive planning, survey of cultural resources, and registration in ·NATIONALthe National Register of REGISTER·Historic Places. BULLETIN U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Interagency Resources Division Nominating Historic Vessels and Shipwrecks to the National Register of Historic Places James P. Delgado and A National Park Service Maritime Task Force* INTRODUCTION For over two hundred years, the United States relied on ships as connective links of a nation. Vessels crossing the Atlantic, Caribbean, and Pacific Oceans, and our inland waters made fundamen tal contributions to colonial settle ment, development of trade, exploration, national defense, and territorial expansion. Unfortunately, we have lost much of this maritime tradition, and most historic vessels have gone to watery graves or have been scrapped by shipbreakers. Many vessels, once renowned or common, now can only be ap preciated in print, on film, on can vas, or in museums. To recognize those cultural resources important in America's past and to encourage their preser vation, Congress expanded the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. Among the ranks of prop erties listed in the National Register are vessels, as well as buildings and structures, such as canals, drydocks, shipyards, and lighthouses that survive to docu ment the Nation's maritime heritage. Yet to date, the National Register has not been fully utilized for listing maritime resources, par ticularly historic vessels. Star of India, The National Register of Historic Places is an important tool FIGURE 1: built in 1863, is now berthed at the San Diego Maritime Museum. for maritime preservation. -

Table 2. Geographic Areas, and Biography

Table 2. Geographic Areas, and Biography The following numbers are never used alone, but may be used as required (either directly when so noted or through the interposition of notation 09 from Table 1) with any number from the schedules, e.g., public libraries (027.4) in Japan (—52 in this table): 027.452; railroad transportation (385) in Brazil (—81 in this table): 385.0981. They may also be used when so noted with numbers from other tables, e.g., notation 025 from Table 1. When adding to a number from the schedules, always insert a decimal point between the third and fourth digits of the complete number SUMMARY —001–009 Standard subdivisions —1 Areas, regions, places in general; oceans and seas —2 Biography —3 Ancient world —4 Europe —5 Asia —6 Africa —7 North America —8 South America —9 Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds —001–008 Standard subdivisions —009 History If “history” or “historical” appears in the heading for the number to which notation 009 could be added, this notation is redundant and should not be used —[009 01–009 05] Historical periods Do not use; class in base number —[009 1–009 9] Geographic treatment and biography Do not use; class in —1–9 —1 Areas, regions, places in general; oceans and seas Not limited by continent, country, locality Class biography regardless of area, region, place in —2; class specific continents, countries, localities in —3–9 > —11–17 Zonal, physiographic, socioeconomic regions Unless other instructions are given, class -

The Story of Christchurch, New Zealand

THE STORY OF CHRISTCHURCH, N.Z. JOHN ROBERT GODLEY, The Founder of Canterbury. THE STORY OF CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND. BY HENRY F. WIGRAM. CHRISTCHURCH: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY THE LYTTELTON TIMES Co., LTH I91B. 430 PREFACE. The story of the foundation and early growth of Canterbury was first told to me, bit by bit, more than thirty years ago, some of it by men and women who had actually taken part in the founding of the settlement, and shaping its destiny, and some by late-comers, who had followed closely on the heels of the pioneers. There were many people then living who delighted in talking of their strenuous life in the pioneering days, " when all the world was young," and in telling of events which are now passing into silent history. Many of the stories I heard then are still vivid in my memory, little episodes illustrating the daily life of a community which had to do everything for itself survey, settle, stock and till the land, build its own roads, bridges and railways, form its own religious, educa- tional, political and social institutions, and construct its own local government. It is no wonder that coming from the valley of the Thames, where the results of centuries of civilisation had come to be accepted as the natural condition of nineteenth century existence, I found the contrast interesting and inspiring. My wife and I were received with the kindly hospi- tality so typical of the time and country. Amongst our immediate neighbours at Upper Riccarton were many old settlers. Mr. -

Return of the Galilee and Construction of a Special Vessel

RETURN OF THE "GALILEE" AND CONSTRUCTION OF A SPECIAL VESSEL. ]By L. A. BAu•z•t, fPD eclo•'. The yacht "Galilee" chartered by the Department Terrestrial 5Iag- netism of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, for the purpose of a general or preliminary magnetic survey of tl•e Pacific Ocean, returned to her home port, San Francisco, California, on May 22, after an absenteeof nearly tt•ree years, during which she has cruised in the Pacific Ocean to the extent of about 65,ooo nautical miles. After completing at San Francisco various swings and observations, she left on August 4, •9o5, for a trial cruise to San Diego, California, under the writer's direction for the purpose of completing the necessary training of the observers and perfecting the ninthotis of observation. The vessel next proceededto Honolulu and Fanning Island, returning to San Diego, California, in December, x9o5. Captain J. F. Pratt of the United States Coast and Geodetic Surx'ey con•manded the vessel in •9o5. Upon the expiration of his furlough, 5rr. •V. J. Peters, chief mag•etic observer of the Department Terrestrial Magnetism, assumed command and carried out the balance of the cruises up to the return to San Francisco in a most satisfactory - manner. During the period m9o6-8,tim vessel visited the following ports: Fanning Island, Apia, (•9o6 and •9o7), Suva, Ja!iut (liarshall Ids., •9o6 and •9o7), Guam, \'okohama, San Diego, Nukahiva (Marquesas Ids.), Tahiti, Yap (Caroline Ids., •9o7), Shanghai, Sitka, Honolulu (•9o7), Lyttleton (New Zealand), Callao (Peru), and San Frm•cisco. It is thus seen that she has cruised over the greater part of the Pacific Ocean and especially in those reg'ions where magnetic data (at least of all three magnetic elements) were very scarce. -

Existing Conditions in the Plan Area

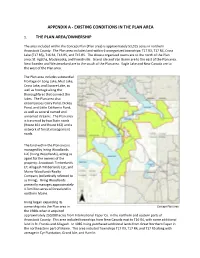

APPENDIX A - EXISTING CONDITIONS IN THE PLAN AREA 1. THE PLAN AREA/OWNERSHIP The area included within the Concept Plan (Plan area) is approximately 51,015 acres in northern Aroostook County. The Plan area includes land within 6 unorganized townships: T17 R3, T17 R4, Cross Lake (T17 R5), T16 R4, T16 R5, and T15 R5. The closest organized towns are to the north of the Plan area: St. Agatha, Madawaska, and Frenchville. Grand Isle and Van Buren are to the east of the Plan area. New Sweden and Westmanland are to the south of the Plan area. Eagle Lake and New Canada are to the west of the Plan area. The Plan area includes substantial frontage on Long Lake, Mud Lake, Cross Lake, and Square Lake, as well as frontage along the thoroughfares that connect the lakes. The Plan area also encompasses Carry Pond, Dickey Pond, and Little California Pond, as well as several named and unnamed streams. The Plan area is traversed by two State roads (Route 161 and Route 162) and a network of forest management roads. The land within the Plan area is managed by Irving Woodlands LLC (Irving Woodlands), acting as agent for the owners of the property: Aroostook Timberlands LP, Allagash Timberlands LLC, and Maine Woodlands Realty Company (collectively referred to as Irving). Irving Woodlands presently manages approximately 1.3 million acres of forestland in northern Maine. Irving began expanding its ownership into the Plan area in Concept Plan area the 1980s when it acquired approximately 250,000 acres from International Paper Co. in the northern and eastern parts of Aroostook County. -

USST International Education 2020.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF SHANGHAI FOR SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY http://ieen.usst.edu.cn/ UNIVERSITY OF SHANGHAI USST FOR SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY WELCOME TO USST SCHOOLS & DEPARTMENTS INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATION INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS CONTENTS HUJIANG INTERNATIONAL CULTURAL PARK OVERSEAS EXPERIENCE UNIVERSITY OF SHANGHAI USST FOR SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY WELCOME TO USST 03 04 UNIVERSITY OF SHANGHAI USST FOR SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY USST Introduction With a history of over 110 years, University of Shanghai for Science and Technology (USST) has many distinctive features and enjoys an excellent reputation nationwide and worldwide. Focusing on engineering-based disciplines, USST has seen a balanced development of other disciplines as engineering, science, economics, management, law, arts and literature, making it an application-research oriented university. It origi- nates from University of Shanghai founded in 1906 and German Medical and Engineering School founded in 1907. At present, USST has a total number of 25,229 students, includ- ing 16,316 undergraduates, 7,721 postgraduate students and 645 PhD candidates. With 16 schools and educational depart- ments, the university has 58 undergraduate majors, 8 first-level disciplines offering doctoral degrees, 4 post-doctoral research stations, 27 first-level disciplines conferring academic master’s degrees and 18 disciplines awarding professional master’s degrees. Currently, USST has 1727 full-time teachers, consisting of top academicians from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Chinese Academy of Engineering, professors and associate professors and researchers with doctoral degree. As one of the earliest universities to start international coopera- tion, the university is now cooperating with more than 172 universities in over 34 countries and regions. There are over 1,000 international students among which 500 of them are pursuing academic degrees.