A Children's Commission for Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.474n/a Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.791 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2020 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government Exports 2500 President Chief Executive 2000 Can. Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam Millions 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of Precio us M etals/ stones Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour M ach. M ech. Elec. Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and Prod. Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Textiles Prod. Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Specialized Inst. Concern Group for Tseung Kwan O People's Livelihood, Democratic Alliance, Kowloon East Food Prod. -

The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster

Mainstream or Alternative? The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster so Ming Hang A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Government and Public Administration © The Chinese University of Hong Kong June 2005 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 卜二,A館書圆^^ m 18 1 KK j|| Abstract Theoretically, public broadcaster and commercial broadcaster are set up and run by two different mechanisms. Commercial broadcaster, as a proprietary organization, is believed to emphasize on maximizing the profit while the public broadcaster, without commercial considerations, is usually expected to achieve some objectives or goals instead of making profits. Therefore, the contribution by public broadcaster to the society is usually expected to be different from those by commercial broadcaster. However, the public broadcasters are in crisis around the world because of their unclear role in actual practice. Many politicians claim that they cannot find any difference between the public broadcasters and the commercial broadcasters and thus they asserted to cut the budget of public broadcasters or even privatize all public broadcasters. Having this unstable situation of the public broadcasting, the role or performance of the public broadcasters in actual practice has drawn much attention from both policy-makers and scholars. Empirical studies are divergent on whether there is difference between public and commercial broadcaster in actual practice. -

LC Paper No. CB(1)1017/17-18(03)

LC Paper No. CB(1)1017/17-18(03) 25th May 2018 Legislative Council Complex 1 Legislative Council Road Central, Hong Kong Dear Members of Legislative Council, Public Hearing on May 28th 2018: Review of relevant provisions under Cap. 586 We write to express our continued support for the Hong Kong Government's commitment to protecting and conserving wildlife, under the Protection of Endangered Species Ordinance (Cap. 586). We are grateful for the government’s recent amendments to Cap. 586, implementing the three-step plan to ban the Hong Kong ivory trade and the increase in maximum penalties under Cap 586. However, there remain challenges for the regulation of wildlife trade in Hong Kong and in tackling wildlife crime, which we suggest addressing through legalisation. The challenges, as we see them, include: The vast scale of the legal trade in shark fins: - In 2017, Hong Kong imported approximately 5,000 metric tonnes (MT) of shark fins1. - Under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), species traded for the seafood and TCM industries, including shark fins, sea cucumber and seahorses, dominated wildlife imports by volume between 2007 to 2016 (87%). - This is all the more concerning, as a recent paper2 revealed that nearly one-third of the species currently identified within the trade in Hong Kong are considered ‘Threatened’ by the IUCN. An illegal trade in shark fins also thrives in Hong Kong: - Out of the 12 endangered shark species internationally protected under CITES regulations, five are known to have been seized as they were trafficked to Hong Kong over the last five years. -

2012 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ELECTION NOMINATIONS for GEOGRAPHICAL CONSTITUENCIES (NOMINATION PERIOD: 18-31 JULY 2012) As at 5Pm, 26 July 2012 (Thursday)

2012 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ELECTION NOMINATIONS FOR GEOGRAPHICAL CONSTITUENCIES (NOMINATION PERIOD: 18-31 JULY 2012) As at 5pm, 26 July 2012 (Thursday) Geographical Date of List (Surname First) Alias Gender Occupation Political Affiliation Remarks Constituency Nomination Hong Kong Island SIN Chung-kai M Politician The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 YEUNG Sum M The Honorary Assistant Professor The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 CHAI Man-hon M District Council Member The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 CHENG Lai-king F Registered Social Worker The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 LEUNG Suk-ching F District Council Member The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 HUI Chi-fung M District Council Member The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island HUI Ching-on M Legal and Financial Consultant 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island IP LAU Suk-yee Regina F Chairperson/Board of Governors New People's Party 18/7/2012 WONG Chor-fung M Public Policy Researcher New People's Party 18/7/2012 TSE Tsz-kei M Community Development Officer New People's Party 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island LAU Kin-yee Miriam F Solicitor Liberal Party 18/7/2012 SHIU Ka-fai M Managing Director Liberal Party 18/7/2012 LEE Chun-keung Michael M Manager Liberal Party 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island LO Wing-lok M Medical Practitioner 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island LAU Gar-hung Christopher M Retirement Benefits Consultant People Power 18/7/2012 SHIU Yeuk-yuen M Company Director 18/7/2012 AU YEUNG Ying-kit Jeff M Family Doctor 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island CHUNG Shu-kun Christopher Chris M Full-time District Councillor Democratic Alliance -

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 3

COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES Original CSES file name: cses2_codebook_part3_appendices.txt (Version: Full Release - December 15, 2015) GESIS Data Archive for the Social Sciences Publication (pdf-version, December 2015) ============================================================================================= COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS (CSES) - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES APPENDIX I: PARTIES AND LEADERS APPENDIX II: PRIMARY ELECTORAL DISTRICTS FULL RELEASE - DECEMBER 15, 2015 VERSION CSES Secretariat www.cses.org =========================================================================== HOW TO CITE THE STUDY: The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (www.cses.org). CSES MODULE 3 FULL RELEASE [dataset]. December 15, 2015 version. doi:10.7804/cses.module3.2015-12-15 These materials are based on work supported by the American National Science Foundation (www.nsf.gov) under grant numbers SES-0451598 , SES-0817701, and SES-1154687, the GESIS - Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, the University of Michigan, in-kind support of participating election studies, the many organizations that sponsor planning meetings and conferences, and the many organizations that fund election studies by CSES collaborators. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in these materials are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding organizations. =========================================================================== IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING FULL RELEASES: This dataset and all accompanying documentation is the "Full Release" of CSES Module 3 (2006-2011). Users of the Final Release may wish to monitor the errata for CSES Module 3 on the CSES website, to check for known errors which may impact their analyses. To view errata for CSES Module 3, go to the Data Center on the CSES website, navigate to the CSES Module 3 download page, and click on the Errata link in the gray box to the right of the page. -

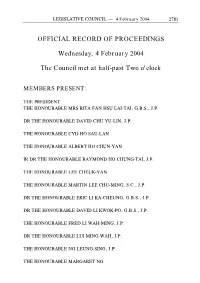

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 4

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 4 February 2004 2781 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 4 February 2004 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID CHU YU-LIN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE ERIC LI KA-CHEUNG, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LUI MING-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE NG LEUNG-SING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG 2782 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 4 February 2004 THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE HUI CHEUNG-CHING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KWOK-KEUNG, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HOWARD YOUNG, S.B.S., J.P. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/BC/5/02

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)1944/02-03 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/BC/5/02 Bills Committee on National Security (Legislative Provisions) Bill Minutes of meeting held on Saturday, 12 April 2003 at 9:00 am in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members : Hon IP Kwok-him, JP (Chairman) present Hon Ambrose LAU Hon-chuen, GBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Kenneth TING Woo-shou, JP Dr Hon David CHU Yu-lin, JP Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Ir Dr Hon Raymond HO Chung-tai, JP Hon Martin LEE Chu-ming, SC, JP Hon Eric LI Ka-cheung, JP Hon Fred LI Wah-ming, JP Hon NG Leung-sing, JP Hon Margaret NG Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon CHEUNG Man-kwong Hon HUI Cheung-ching, JP Hon CHAN Kwok-keung Hon Bernard CHAN, JP Hon CHAN Kam-lam, JP Hon LEUNG Yiu-chung Hon SIN Chung-kai Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong Hon WONG Yung-kan Hon Jasper TSANG Yok-sing, GBS, JP Hon Howard YOUNG, JP Hon YEUNG Yiu-chung, BBS Hon LAU Kong-wah Hon Miriam LAU Kin-yee, JP - 2 - Hon CHOY So-yuk Hon Andrew CHENG Kar-foo Hon SZETO Wah Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, JP Hon Henry WU King-cheong, BBS, JP Hon Michael MAK Kwok-fung Hon LEUNG Fu-wah, MH, JP Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Hon MA Fung-kwok, JP Members : Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan absent Hon LEE Cheuk-yan Dr Hon LUI Ming-wah, JP Hon Mrs Selina CHOW LIANG Shuk-yee, GBS, JP Hon Andrew WONG Wang-fat, JP Hon LAU Chin-shek, JP Hon LAU Wong-fat, GBS, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, SBS, JP Dr Hon LAW Chi-kwong, JP Dr Hon TANG Siu-tong, JP Dr Hon LO Wing-lok -

Hansard (English)

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 10 November 1999 1053 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 10 November 1999 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE KENNETH TING WOO-SHOU, J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE DAVID CHU YU-LIN THE HONOURABLE HO SAI-CHU, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL HO MUN-KA IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE WING-TAT THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ERIC LI KA-CHEUNG, J.P. 1054 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 10 November 1999 THE HONOURABLE LEE KAI-MING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LUI MING-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE NG LEUNG-SING PROF THE HONOURABLE NG CHING-FAI THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONALD ARCULLI, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MA FUNG-KWOK THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE AMBROSE CHEUNG WING-SUM, J.P. THE HONOURABLE HUI CHEUNG-CHING THE HONOURABLE CHAN KWOK-KEUNG THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN THE HONOURABLE CHAN WING-CHAN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM DR THE HONOURABLE LEONG CHE-HUNG, J.P. LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 10 November 1999 1055 THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, J.P. -

To the Wisdom of the Masses

Listening to the wisdom of the masses Hong Kong people’s attitudes toward constitutional reform (January 2004) A survey commissioned by Civic Exchange conducted and analyzed by the Hong Kong Transition Project Visit us at: www.civic-exchange.org ROOM 701, HOSEINEE HOUSE, 69 WYNDHAM STREET, CENTRAL, HONG KONG TEL: (852) 2893-0213 FAX: (852) 3105-9713 Table of Contents Executive summary 2 Introduction 4 The Framework for Constitutional Reform 4 The Framework for Survey Analysis 7 List of key variables Table 1: Birthplace 9 Table 2: Which of the following categories do you think you fall into? Table 3: Reclassified Affiliation identity categories 10 Table 4: Affiliation Identity by birthplace Table 5 The following is a list of how you might describe yourself. Which is the most appropriate description of you? Table 6: Patriotic Identity choices 11 Table 7: Patriotic Identity by Birthplace 12 Table 8: Patriotic Identity by Age Group Part I Attitudes toward current processes of government Table 9: Are you currently satisfied or dissatisfied with the general performance of 14 the HKG? Table 10: Intensity of Satisfaction / Dissatisfaction with performance of HKG 15 Table 11: Reclassified Satisfaction / Dissatisfaction with performance of HKG Table 12: Satisfaction with HKG performance by Birthplace Table 13: Satisfaction with HKG performance by Age group Chart of Table 13: Satisfaction with HKG performance by Age group 16 Table 14: Satisfaction with performance of HKG by Education level Chart of Table 14: Satisfaction with performance of HKG -

Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: Results of the 2012 Elections

Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: Results of the 2012 Elections Michael F. Martin Acting Section Research Manager/Specialist in Asian Affairs September 14, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R42746 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: Results of the 2012 Elections Summary Hong Kong selected a new Chief Executive and Legislative Council (Legco) in March and September of 2012, respectively. Both elections delivered surprising results for different reasons. The eventual selection of Leung Chu-ying (CY Leung) as Chief Executive came after presumed front-runner Henry Tang Ying-yen ran into a series of personal scandals. The Legco election results surprised many as several of the traditional parties fared poorly while several new parties emerged victorious. The 2012 elections in Hong Kong are important for the city’s future prospect for democratic reforms because, under the territory’s Basic Law, any changes in the election process for Chief Executive and Legco must be approved by two-thirds of the Legco members and receive the consent of the Chief Executive. Under the provision of a decision by China’s Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress issued in December 2007, the soonest that the Chief Executive and all the Legco members can be elected by universal suffrage are the elections of 2017 and 2020, respectively. As such, the newly elected Legco and CY Leung will have the opportunity to propose and adopt election reforms that fulfill the “ultimate aim” of the election of Hong Kong’s leaders by universal suffrage. -

Should Live Fish Be Regarded As Food?

Proposed Legislative Amendment in Hong Kong: Should Live Fish Be Regarded As Food? by Thierry T.C. Chan www.civic-exchange.org September 2006 Proposed Legislative Amendment in Hong Kong: Should Live Fish Be Regarded As Food? by Thierry Tak-chuen Chan September 2006 www.civic-exchange.org Civic Exchange Room 701, Hoseinee House, 69 Wyndham Street, Central, Hong Kong. Tel: (852) 2893-0213 Fax: (852) 3105-9713 Civic Exchange is a non-profit organisation that helps to improve policy and decision-making through research and analysis. 1 Legislative Amendment in Hong Kong: Should Live Fish Be Regarded As Food? TABLE OF CONTENTS page RECOMMENDATIONS 1 SECTION 1 OVERVIEW 2 1.1 Background 2 1.2 Import of live food fish 6 1.3 Government framework 9 1.4 Legco documents 11 1.5 Existing ordinances 15 1.6 Ciguatera 17 SECTION 2 QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEY 26 2.1 Inception 26 2.2 Survey 27 2.3 Results 28 2.4 Evaluation of the questionnaire survey 29 SECTION 3 DISCUSSION 30 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 32 REFERENCES 33 TABLES APPENDICES Disclaimer: The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily represents the opinions of Civic Exchange. Legislative Amendment in Hong Kong: Should Live Fish Be Regarded As Food? LIST OF APPENDICES APPENDIX I Questionnaire (English version) APPENDIX II Questionnaire (Chinese version) LIST OF TABLES TABLE 1 Estimated quantity (in metric tonnes) and monetary value (in HK$ million) of live freshwater and marine fish imported into Hong Kong from 2000 to 2005 TABLE 2 Estimated quantity (in metric tonnes) and monetary -

CSESII Parties and Leaders Original CSES Text Plus CCNER Additions (Highlighted)

CSESII Parties and Leaders Original CSES text plus CCNER additions (highlighted) =========================================================================== ))) APPENDIX I: PARTIES AND LEADERS =========================================================================== | NOTES: PARTIES AND LEADERS | | This appendix identifies parties active during a polity's | election and (where available) their leaders. | | Provided are the party labels for the codes used in the micro | data variables. Parties A through F are the six most popular | parties, listed in descending order according to their share of | the popular vote in the "lowest" level election held (i.e., | wherever possible, the first segment of the lower house). | | Note that in countries represented with more than a single | election study the order of parties may change between the two | elections. | | Leaders A through F are the corresponding party leaders or | presidential candidates referred to in the micro data items. | This appendix reports these names and party affiliations. | | Parties G, H, and I are supplemental parties and leaders | voluntarily provided by some election studies. However, these | are in no particular order. --------------------------------------------------------------------------- >>> PARTIES AND LEADERS: ALBANIA (2005) --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 02. Party A PD Democratic Party Sali Berisha 01. Party B PS Socialist Party Fatos Nano 04. Party C PR Republican Party Fatmir Mediu 05. Party D PSD Social Democratic Party Skender Gjinushi 03. Party E LSI Socialist Movement for Integration Ilir Meta 10. Party F PDR New Democratic Party Genc Pollo 09. Party G PAA Agrarian Party Lufter Xhuveli 08. Party H PAD Democratic Alliance Party Neritan Ceka 07. Party I PDK Christian Democratic Party Nikolle Lesi 06. LZhK Movement of Leka Zogu I Leka Zogu 11. PBDNj Human Rights Union Party 12. Union for Victory (Partia Demokratike+ PR+PLL+PBK+PBL) 89.