Executive-Legislative Disconnection in Post-Colonial Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

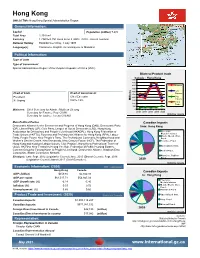

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.474n/a Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.791 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2020 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government Exports 2500 President Chief Executive 2000 Can. Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam Millions 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of Precio us M etals/ stones Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour M ach. M ech. Elec. Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and Prod. Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Textiles Prod. Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Specialized Inst. Concern Group for Tseung Kwan O People's Livelihood, Democratic Alliance, Kowloon East Food Prod. -

Macro Report August 23, 2004

Prepared by: LI Pang-kwong, Ph.D. Date: 10 April 2005 Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 2: Macro Report August 23, 2004 Country: Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, CHINA Date of Election: 12 September 2004 NOTE TO COLLABORATORS: The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Part I: Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1. Report the number of portfolios (cabinet posts) held by each party in cabinet, prior to the most recent election. (If one party holds all cabinet posts, simply write "all".) In the context of Hong Kong, the Executive Council (ExCo) can be regarded as the cabinet. The ExCo comprises the Official Members (all the Principal Officials in the Government Secretariat have been appointed concurrently the Official Members of the ExCo since July 2002) and the Non-official Members. The members of the ExCo are appointed by the Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), while the Principal Officials are nominated by the Chief Executive and are appointed by the Central People’s Government of China. Name of Political Party Number of Portfolios Official Members (with portfolios) of the Executive Council: All the Official Members do not have party affiliation. Non-official Members (without portfolio) of the Executive Council: 1. Democratic Alliance for Betterment of Hong Kong 1 2. -

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 1399 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 3 November 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 1400 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. -

The Status of Cantonese in the Education Policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung*

Lee and Leung Multilingual Education 2012, 2:2 http://www.multilingual-education.com/2/1/2 RESEARCH Open Access The status of Cantonese in the education policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung* * Correspondence: waimun@ied. Abstract edu.hk Department of Chinese, The Hong After the handover of Hong Kong to China, a first-ever policy of “bi-literacy and Kong Institute of Education, Hong tri-lingualism” was put forward by the Special Administrative Region Government. Kong Under the trilingual policy, Cantonese, the most dominant local language, equally shares the official status with Putonghua and English only in name but not in spirit, as neither the promotion nor the funding approaches on Cantonese match its legal status. This paper reviews the status of Cantonese in Hong Kong under this policy with respect to the levels of government, education and curriculum, considers the consequences of neglecting Cantonese in the school curriculum, and discusses the importance of large-scale surveys for language policymaking. Keywords: the status of Cantonese, “bi-literacy and tri-lingualism” policy, language survey, Cantonese language education Background The adjustment of the language policy is a common phenomenon in post-colonial societies. It always results in raising the status of the regional vernacular, but the lan- guage of the ex-colonist still maintains a very strong influence on certain domains. Taking Singapore as an example, English became the dominant language in the work- place and families, and the local dialects were suppressed. It led to the degrading of both English and Chinese proficiency levels according to scholars’ evaluation (Goh 2009a, b). -

Formation of Legco -Eng

LC Paper No. CB(2)1971/05-06(02) Legislative Council Panel on Constitutional Affairs Discussion regarding the formation of the Legislative Council by universal suffrage Introduction This paper provides relevant information for Members’ reference on the following discussion items proposed by the Democratic Party: (a) method for forming the Legislative Council (LegCo) by universal suffrage and the future of functional constituencies (FCs); and (b) delineation of geographical constituencies and the system of voting when all LegCo Members are returned by universal suffrage. Method for forming LegCo by universal suffrage and the future of FCs 2. Article 68 of the Basic Law provides that “the LegCo of the HKSAR shall be constituted by election. The method for forming the LegCo shall be specified in the light of actual situation in the HKSAR and in accordance with the principle of gradual and orderly progress. The ultimate aim is the election of all members of LegCo by universal suffrage.” In accordance with the Decision made by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPCSC) of April 2004, the ratio between members returned by FCs and members returned by geographical constituencies (GCs) through direct elections, who shall respectively occupy half of the seats, is to remain unchanged. 3. At its meeting in November 2005, the Committee on Governance and Political Development of the Commission on Strategic Development (CSD) explored preliminarily the possible models for forming the LegCo when the ultimate aim of universal suffrage is attained (including the unicameral and bicameral systems) and the issues to be considered. The CSD Secretariat has provided to LegCo the relevant discussion paper (CB(2)519/05-06(2)). -

The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster

Mainstream or Alternative? The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster so Ming Hang A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Government and Public Administration © The Chinese University of Hong Kong June 2005 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 卜二,A館書圆^^ m 18 1 KK j|| Abstract Theoretically, public broadcaster and commercial broadcaster are set up and run by two different mechanisms. Commercial broadcaster, as a proprietary organization, is believed to emphasize on maximizing the profit while the public broadcaster, without commercial considerations, is usually expected to achieve some objectives or goals instead of making profits. Therefore, the contribution by public broadcaster to the society is usually expected to be different from those by commercial broadcaster. However, the public broadcasters are in crisis around the world because of their unclear role in actual practice. Many politicians claim that they cannot find any difference between the public broadcasters and the commercial broadcasters and thus they asserted to cut the budget of public broadcasters or even privatize all public broadcasters. Having this unstable situation of the public broadcasting, the role or performance of the public broadcasters in actual practice has drawn much attention from both policy-makers and scholars. Empirical studies are divergent on whether there is difference between public and commercial broadcaster in actual practice. -

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: a Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Tso, Elizabeth Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 12:25:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623063 DISCOURSE, SOCIAL SCALES, AND EPIPHENOMENALITY OF LANGUAGE POLICY: A CASE STUDY OF A LOCAL, HONG KONG NGO by Elizabeth Ann Tso __________________________ Copyright © Elizabeth Ann Tso 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Elizabeth Tso, titled Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO, and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Perry Gilmore _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Wenhao Diao _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Sheilah Nicholas Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy

Loyola University Chicago International Law Review Volume 3 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring/Summer 2006 2006 The aB sic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong Michael C. Davis Chinese University of Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael C. Davis The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy. U. Chi. Int'l L. Rev. 165 (2006). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr/vol3/iss2/5 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago International Law Review by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BASIC LAW AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN HONG KONG Michael C. Davist I. Introduction Hong Kong's status as a Special Administrative Region of China has placed it on the foreign policy radar of most countries having relations with China and interests in Asia. This interest in Hong Kong has encouraged considerable inter- est in Hong Kong's founding documents and their interpretation. Hong Kong's constitution, the Hong Kong Basic Law ("Basic Law"), has sparked a number of debates over democratization and its pace. It is generally understood that greater democratization will mean greater autonomy and vice versa, less democracy means more control by Beijing. For this reason there is considerable interest in the politics of interpreting Hong Kong's Basic Law across the political spectrum in Hong Kong, in Beijing and in many foreign capitals. -

Is Poverty Eradication Impossible? a Critique on the Misconceptions of the Hong Kong Government • Hung Wong

STARTING3 ISSUES FROM PER YEAR2016 The China Review An Interdisciplinary Journal on Greater China Volume 15 Number 2 Fall 2015 Special Issue Introduction: Poverty in a Rich Society—The Case of Hong Kong • Maggie Lau (Guest Editor) My Experience Researching Poverty over the Past 35 Years • Nelson W. S. Chow Poverty in Hong Kong • Maggie Lau, Christina Pantazis, David Gordon, Lea Lai, and Eileen Sutton Setting the Poverty Line: Policy Implications for Squaring the Welfare Circle in Volume 15 Number 2 Fall 2015 Hong Kong • Florence Meng-soi Fong and Chack-kie Wong Health Inequality in Hong Kong • Roger Y. Chung and Samuel Y. S. Wong An Interdisciplinary Enhancing Global Competitiveness and Human Capital Management: Does Journal on Education Help Reduce Inequality and Poverty in Hong Kong? • Ka Ho Mok Greater China Is Poverty Eradication Impossible? A Critique on the Misconceptions of the Hong Kong Government • Hung Wong Book Reviews Special Issue Poverty in a Rich Society Vol. 15, No. 2, Fall 2015 2, Fall 15, No. Vol. —The Case of Hong Kong Available online via ProQuest Asia Business & Reference Project MUSE at http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/china_review/ JSTOR at http://www.jstor.org/journal/chinareview STARTING3 ISSUES FROM PER YEAR2016 The China Review An Interdisciplinary Journal on Greater China Volume 15 Number 2 Fall 2015 Special Issue Introduction: Poverty in a Rich Society—The Case of Hong Kong • Maggie Lau (Guest Editor) My Experience Researching Poverty over the Past 35 Years • Nelson W. S. Chow Poverty in Hong Kong • Maggie Lau, Christina Pantazis, David Gordon, Lea Lai, and Eileen Sutton Setting the Poverty Line: Policy Implications for Squaring the Welfare Circle in Volume 15 Number 2 Fall 2015 Hong Kong • Florence Meng-soi Fong and Chack-kie Wong Health Inequality in Hong Kong • Roger Y. -

Civic Party (Cp)

立法會 CB(2)1335/17-18(04)號文件 LC Paper No. CB(2)1335/17-18(04) CIVIC PARTY (CP) Submission to the United Nations UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) CHINA 31st session of the UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council November 2018 Introduction 1. We are making a stakeholder’s submission in our capacity as a political party of the pro-democracy camp in Hong Kong for the 2018 Universal Periodic Review on the People's Republic of China (PRC), and in particular, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Currently, our party has five members elected to the Hong Kong Legislative Council, the unicameral legislature of HKSAR. 2. In the Universal Periodic Reviews of PRC in 2009 and 2013, not much attention was paid to the human rights, political, and social developments in the HKSAR, whilst some positive comments were reported on the HKSAR situation. i We wish to highlight that there have been substantial changes to the actual implementation of human rights in Hong Kong since the last reviews, which should be pinpointed for assessment in this Universal Periodic Review. In particular, as a pro-democracy political party with members in public office at the Legislative Council (LegCo), we wish to draw the Council’s attention to issues related to the political structure, election methods and operations, and the exercise of freedom and rights within and outside the Legislative Council in HKSAR. Most notably, recent incidents demonstrate that the PRC and HKSAR authorities have not addressed recommendations made by the Human Rights Committee in previous concluding observations in assessing the implementation of International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). -

LC Paper No. CB(1)1017/17-18(03)

LC Paper No. CB(1)1017/17-18(03) 25th May 2018 Legislative Council Complex 1 Legislative Council Road Central, Hong Kong Dear Members of Legislative Council, Public Hearing on May 28th 2018: Review of relevant provisions under Cap. 586 We write to express our continued support for the Hong Kong Government's commitment to protecting and conserving wildlife, under the Protection of Endangered Species Ordinance (Cap. 586). We are grateful for the government’s recent amendments to Cap. 586, implementing the three-step plan to ban the Hong Kong ivory trade and the increase in maximum penalties under Cap 586. However, there remain challenges for the regulation of wildlife trade in Hong Kong and in tackling wildlife crime, which we suggest addressing through legalisation. The challenges, as we see them, include: The vast scale of the legal trade in shark fins: - In 2017, Hong Kong imported approximately 5,000 metric tonnes (MT) of shark fins1. - Under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), species traded for the seafood and TCM industries, including shark fins, sea cucumber and seahorses, dominated wildlife imports by volume between 2007 to 2016 (87%). - This is all the more concerning, as a recent paper2 revealed that nearly one-third of the species currently identified within the trade in Hong Kong are considered ‘Threatened’ by the IUCN. An illegal trade in shark fins also thrives in Hong Kong: - Out of the 12 endangered shark species internationally protected under CITES regulations, five are known to have been seized as they were trafficked to Hong Kong over the last five years.