PC.17.2.FULL.Pdf (5.839Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Dog Off-Leash Area in Lawren Harris Square

City of Toronto – Parks, Forestry & Recreation Proposed Dog Off-Leash Area in Lawren Harris Square Survey Summary Report May 16, 2021 Rajesh Sankat, Senior Public Consultation Coordinator Alex Lavasidis, Senior Public Consultation Coordinator 1 Contents Project Background .................................................................................................................... 3 Survey Objectives ...................................................................................................................... 5 Notification ................................................................................................................................. 5 Key Feedback Summary ............................................................................................................ 5 Next Steps ................................................................................................................................. 4 Appendix A: Quantitative Response Summary ........................................................................... 5 Appendix B: Location ................................................................................................................. 7 Appendix C: Text Responses ..................................................................................................... 8 Appendix D: Email Responses ..................................................................................................66 2 Project Background Based on high demand from local residents, the City is considering the installation -

Rethinking Toronto's Middle Landscape: Spaces of Planning, Contestation, and Negotiation Robert Scott Fiedler a Dissertation S

RETHINKING TORONTO’S MIDDLE LANDSCAPE: SPACES OF PLANNING, CONTESTATION, AND NEGOTIATION ROBERT SCOTT FIEDLER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GEOGRAPHY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO May 2017 © Robert Scott Fiedler, 2017 Abstract This dissertation weaves together an examination of the concept and meanings of suburb and suburban, historical geographies of suburbs and suburbanization, and a detailed focus on Scarborough as a suburban space within Toronto in order to better understand postwar suburbanization and suburban change as it played out in a specific metropolitan context and locale. With Canada and the United States now thought to be suburban nations, critical suburban histories and studies of suburban problems are an important contribution to urbanistic discourse and human geographical scholarship. Though suburbanization is a global phenomenon and suburbs have a much longer history, the vast scale and explosive pace of suburban development after the Second World War has a powerful influence on how “suburb” and “suburban” are represented and understood. One powerful socio-spatial imaginary is evident in discourses on planning and politics in Toronto: the city-suburb or urban-suburban divide. An important contribution of this dissertation is to trace out how the city-suburban divide and meanings attached to “city” and “suburb” have been integral to the planning and politics that have shaped and continue to shape Scarborough and Toronto. The research employs an investigative approach influenced by Michel Foucault’s critical and effective histories and Bent Flyvbjerg’s methodological guidelines for phronetic social science. -

Gentrification Reconsidered: the Case of the Junction

Gentrification Reconsidered: The Case of The Junction By: Anthony Ruggiero Submitted: July 31th, 2014 A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies (Urban Planning) Faculty of Environmental Studies York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada __________________________ ___________________________ Anthony Ruggiero John Saunders, PhD MES Candidate Supervisor ii Abstract This paper examines the factors responsible for the gentrification of The Junction, a west-end neighbourhood located on the edge of downtown Toronto. After years of neglect, degradation and deindustrialization, The Junction is currently in the midst of being gentrified. Through various forms of neighbourhood upgrading and displacement, gentrification has been responsible for turning a number working-class Toronto neighbourhoods into middle-class enclaves. The Junction is unique in this regard because it does not conform to past theoretical perspectives regarding gentrification in Toronto. Through the use of an instrumental case-study, various factors responsible for The Junction’s gentrification are examined and a number of its indicators that are present in the neighbourhood are explored so that a solid understanding regarding the neighbourhood’s gentrification can be realized. What emerges is a form of ‘user-friendly’ or ‘community-driven’ gentrification that places emphasis on neighbourhood revitalization and community inclusion, as opposed to resident displacement -

923466Magazine1final

www.globalvillagefestival.ca Global Village Festival 2015 Publisher: Silk Road Publishing Founder: Steve Moghadam General Manager: Elly Achack Production Manager: Bahareh Nouri Team: Mike Mahmoudian, Sheri Chahidi, Parviz Achak, Eva Okati, Alexander Fairlie Jennifer Berry, Tony Berry Phone: 416-500-0007 Email: offi[email protected] Web: www.GlobalVillageFestival.ca Front Cover Photo Credit: © Kone | Dreamstime.com - Toronto Skyline At Night Photo Contents 08 Greater Toronto Area 49 Recreation in Toronto 78 Toronto sports 11 History of Toronto 51 Transportation in Toronto 88 List of sports teams in Toronto 16 Municipal government of Toronto 56 Public transportation in Toronto 90 List of museums in Toronto 19 Geography of Toronto 58 Economy of Toronto 92 Hotels in Toronto 22 History of neighbourhoods in Toronto 61 Toronto Purchase 94 List of neighbourhoods in Toronto 26 Demographics of Toronto 62 Public services in Toronto 97 List of Toronto parks 31 Architecture of Toronto 63 Lake Ontario 99 List of shopping malls in Toronto 36 Culture in Toronto 67 York, Upper Canada 42 Tourism in Toronto 71 Sister cities of Toronto 45 Education in Toronto 73 Annual events in Toronto 48 Health in Toronto 74 Media in Toronto 3 www.globalvillagefestival.ca The Hon. Yonah Martin SENATE SÉNAT L’hon Yonah Martin CANADA August 2015 The Senate of Canada Le Sénat du Canada Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4 K1A 0A4 August 8, 2015 Greetings from the Honourable Yonah Martin Greetings from Senator Victor Oh On behalf of the Senate of Canada, sincere greetings to all of the organizers and participants of the I am pleased to extend my warmest greetings to everyone attending the 2015 North York 2015 North York Festival. -

2006 Community Management Plan

43043 CMPcover06 3/8/06 10:15 AM Page 1 Toronto Community Housing Community Management Plan 2006 | 2007 | 2008 Table of Contents At-A-Glance Introduction ............................................................................ 1 2006 | 2007 | 2008 Investment Plan ............................................... 5 Strategic Focus Areas................................................................ 17 Focus on Communities .......................................................... 19 Focus on Organization .......................................................... 47 Focus on City Building .......................................................... 59 Focus on Governance ........................................................... 73 Implementation ...................................................................... 85 Appendices A: Toronto Community Housing Background B: Toronto Community Housing Portfolio C: Stakeholder Consultation D: Community Partners E: 2005 Report Card 4430433043 TTCH_Plan.inddCH_Plan.indd 1 33/9/06/9/06 112:58:462:58:46 PPMM 4430433043 TTCH_Plan.inddCH_Plan.indd 2 33/8/06/8/06 111:26:061:26:06 AAMM Communities Commitments At-A-Glance 1.1 | ASSET IMPROVEMENT 2006 2007 |2008 1.1.1 ! Implement Phase 1 of the program. ! Allocate 2007 and 2008 funds. Building Renewal ! Initiate an Energy Performance ! Evaluate ongoing projects. Program Monitoring and Verification Plan. Building retrofit utilizing ! Evaluate the site selection process savings gained through for Phase 2 of program. energy efficiencies to finance other -

"Reform" As a Chaotic Concept: the Case of Toronto Jon Caulfield

Document generated on 09/26/2021 8:41 p.m. Urban History Review Revue d'histoire urbaine "Reform" as a Chaotic Concept: The Case of Toronto Jon Caulfield Volume 17, Number 2, October 1988 Article abstract Contemporary "reformism" in Canadian cities is frequently treated, explicitly URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1017656ar or implicitly, as a coherent urban political movement and as a movement that DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1017656ar has been oriented to "anti-developmentism." In the case of Toronto neither characterization is accurate: "reform" has been neither a coherent movement See table of contents nor "anti-development." Publisher(s) Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine ISSN 0703-0428 (print) 1918-5138 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Caulfield, J. (1988). "Reform" as a Chaotic Concept: The Case of Toronto. Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 17(2), 107–111. https://doi.org/10.7202/1017656ar All Rights Reserved © Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 1988 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ "Reform" as a Chaotic Concept: The Case of Toronto Jon Caulfield Abstract Contemporary "reformism" in John Weaver has demurred from Paul the other hand, I find Sancton's view Canadian cities is frequently treated, Rutherford's characterization of turn-of-the- ultimately wrong-headed because, in two key explicitly or implicitly, as a coherent century Canadian urban "reformism" as a ways, it shares similar misconceptions with urban political movement and as a movement based on the principle that "city the work of Burton and Morley. -

2013-05-TFN-Newsletter.Pdf

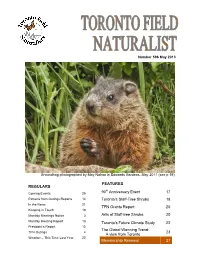

Number 596 May 2013 Groundhog photographed by Moy Nahon in Edwards Gardens, May 2011 (see p 19) FEATURES REGULARS th Coming Events 25 90 Anniversary Event 17 Extracts from Outings Reports 14 Toronto’s Staff-Tree Shrubs 18 In the News 21 TFN Grants Report 20 Keeping in Touch 19 Monthly Meetings Notice 3 Arils of Staff-tree Shrubs 20 Monthly Meeting Report 13 Toronto’s Future Climate Study 22 President’s Report 12 The Global Warming Trend: TFN Outings 4 23 A view from Toronto Weather – This Time Last Year 22 Membership Renewal 27 TFN 596-2 May 2013 Toronto Field Naturalist is published by the Toronto Field BOARD OF DIRECTORS Naturalists, a charitable, non-profit organization, the aims of President & Outings Margaret McRae which are to stimulate public interest in natural history and Past President Bob Kortright to encourage the preservation of our natural heritage. Issued Vice President & monthly September to December and February to May. Monthly Lectures Nancy Dengler Views expressed in the Newsletter are not necessarily those Secretary-Treasurer Charles Crawford of the editor or Toronto Field Naturalists. The Newsletter is Communications Alexander Cappell printed on 100% recycled paper. Membership & Newsletter Judy Marshall ISSN 0820-636X Monthly Lectures Corinne McDonald Monthly Lectures Lavinia Mohr IT’S YOUR NEWSLETTER! Nature Reserves & Charles Bruce- We welcome contributions of original writing of observa- Outings Thompson tions on nature in and around Toronto (up to 500 words). Outreach Tom Brown We also welcome reports, reviews, poems, sketches, pain- Webmaster Lynn Miller tings and digital photographs. Please include “Newsletter” in the subject line when sending by email, or on the MEMBERSHIP FEES envelope if sent by mail. -

King Parliament Secondary Plan Review Open House

BUILT FORM King-Parliament Then and Now A major objective of the King-Parliament Secondary Plan is to encourage redevelopment of the area through THEN NOW the reinvestment and re-use of existing buildings. All new development is required to be “mutually compatible and complement the existing built form character and scale of the area,” (Policy 2.2). Many developments in the area achieve this objective but over time there has been an incremental increase in tall building applications with greater building mass. This trend is deviating from the built form direction of the Secondary Plan. This series of photographs shows specifi c sites in the King-Parliament area in 1996 and today. They show that some blocks have remained unchanged while others have been adaptively re-used and further developed. Distillery District THEN NOW 145 Eastern Ave. 2 Eastern Ave. Wilkins Ave. 116 George St. King St. E. today 457-463 King St. E. 300 Adelaide St. E. BUILT FORM JARVIS PARLIAMENT Existing Policy Direction • The Jarvis Parliament area is targeted for signifi cant growth, with a mix of compatible land uses including commercial, industrial, institutional, residential, live/work and entertainment uses within new buildings and existing ones, including the numerous historically and architecturally signifi cant buildings in the area. • New residential uses must be complementary to King-Parliament’s role as a business area, providing an incentive for the retention of existing buildings, especially those of architectural or heritage merit. Map 15-1 of the existing King-Parliament Secondary Plan identifi es different policy areas. The Jarvis-Parliament Regeneration Area is shown in green. -

Novae Res Urbis

FRIDAY, JUNE 16, 2017 REFUSAL 3 20 YEARS LATER 4 Replacing rentals Vol. 21 Stronger not enough No. 24 t o g e t h e r 20TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION NRU TURNS 20! AND THE STORY CONTINUES… Dominik Matusik xactly 20 years ago today, are on our walk selling the NRU faxed out its first City neighbourhood. But not the E of Toronto edition. For the developers. The question is next two decades, it covered whether the developers will the ups and downs of the city’s join the walk.” planning, development, and From 2017, it seems like municipal affairs news, though the answer to that question is a email has since replaced the fax resounding yes. machine. Many of the issues “One of the innovative the city cared about in 1997 still parts of the Regent Park resonate in 2017. From ideas for Revitalization,” downtown the new Yonge-Dundas Square city planning manager David to development charges along Oikawa wrote in an email the city’s latest subway line and to NRU, “was the concept of trepidations about revitalizing using [condos] to fund the Regent Park. It was an eventful needed new assisted public year. housing. A big unknown at The entire first edition of Novæ Res Urbis (2 pages), June 16, 1997 Below are some headlines from the time was [whether] that NRU’s first year and why these concept [would] work. Would issues continue to captivate us. private home owners respond to the idea of living and New Life for Regent Park investing in a mixed, integrated (July 7, 1997) community? Recently, some condo townhouses went on sale In 1997, NRU mused about the in Regent Park and were sold future of Regent Park. -

Public Project, Private Developer: Understanding the Impact of Local

Public project, private developer: Understanding the impact of local policy frameworks on the public-private housing redevelopment of Regent Park in Toronto, Ontario by Trevor Robinson A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Geography and Planning in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2017 Copyright © Trevor Robinson, 2017 Abstract This thesis examines Regent Park, a public housing community in Toronto, Ontario undergoing mixed-income revitalization through a public-private partnership (3P) since 2006. Much of the existing literature has studied the Regent Park revitalization from the perspective of public housing tenants, conceptualizing the project as a continuation of redevelopment efforts in the United States. However, this approach neglects the unique Canadian policy context and the point-of-view of industry professionals involved in the development process. Using Toronto as the primary lens of geographic analysis to study the revitalization, a qualitative, mixed- methods approach was employed in this thesis to focus on the local policy context and perspective of individuals involved in the Regent Park redevelopment process. Data was gathered, primarily, through interviews with 25 public and private sector professionals. Subsequent analysis generated several findings and recommendations for application at Regent Park and 3P redevelopment efforts in Toronto and other cities. Where many recent studies depict the Regent Park revitalization as having an overall negative outcome for public housing tenants and other public shareholders, this thesis, in contrast, found that the project is delivering notable social benefits to Regent Park and surrounding communities, while avoiding the displacement of low-income residents characteristic of public housing redevelopment in the US. -

Planning and Design in Ontario: Then and Now Today’S City Is Not an Accident

Planning and Design in Ontario: Then and Now Today’s city is not an accident. Its form is usually unintentional, but it is not accidental. It is the product of decisions made for single, separate purposes, whose interrelationships and side effects have not been fully considered. J. Barnett, An Introduction to Urban Design, Harper & Row, NY, 1982, p. 9 2 planning graffiti from the seventies “The Good Life” “Little thought was given to three‐dimensional urban form or to landscape architecture. Design emphasis was on well drained, easily maintained development with a maximum capacity for the free flow of vehicles.” Max Bacon, Architect Planner, Plan Canada, Planning (?) in Ontario prior to 1977, p. 115 before 1980 - 1989 1990 - 1999 2000 - 2009 2010 in the early days 3 Looking outwards…unstructured sprawl Looking Inwards…Regent Park: An Isolated Garden Source: skyscarpercity.com 1972 1952 Lawrence Avenue & Don Valley Parkway 1952 & 1972 Regent Park South advertising circa late 1950s post World War II 4 Genesis of public participation in the planning process Source: Ian Land clearing south of Lawrence Ave. MacEachern for the Spadina Expressway Trefann Court Neighbourhood in 1968 “What we want is to have urban renewal called off. No expropriation, no demolition, no bargaining about prices; the city [Toronto] should go away and leave us alone….” 1971 Provincial cancellation of Spadina Expressway 1960s - 1979 5 Retail focus and emergence of urban design Peterborough Square, constructed 1975 St. Lawrence Neighbourhood, Toronto Bloor West Village, -

Reasons to Call Toronto Home

RIVER & FIFTH TORONTO BROCCOLINI 2 3 The fusion of nature and city illuminate along the river’s edge. RIVER & FIFTH TORONTO BROCCOLINI Are you ready 4 for the rise of 5 River & Fifth? RIVER & FIFTH TORONTO BROCCOLINI 6 7 Here in Corktown, a 37-storey glass tower and podium emerge to become an instant icon. The trails and surrounding parks guide your path home, leading to a grand lobby that brings the outside in. Modern. Sophisticated. It’s the urban oasis you’ve been waiting for. BROCCOLINI LOCATION BAKERIES MAP & CAFES PARKS & TRAILS 1. Tori’s Bake Shop 19. Regent Park North 2. The Cannonball Coffee and Bar 20. Oak Street Park 3. Starbucks 21. Joel Weeks Park 4. Roselle Deserts 22. Corktown Common 26 5. Balzac’s Distillery District 23. Lower Don River Trail 24. Orphans Green Dog Park CABBAGETOWN DVP 31 SOUTH RIVERDALE 27 FITNESS SCHOOLS & RECREATION RIVERSIDE LESLIEVILLE 32 25. Inglenook Community School TREFANN COURT 6. Underpass Park 26. University of Toronto 7. Lift Corktown - St.George Campus CORKTOWN 8. Toronto Cooper Koo Family DOWNTOWN 27. Ryerson University EAST 9. Pam McConnell Aquatic Centre DISTILLERY STUDIO DISTRICT HARBOUR 10. Riverdale Farm OLD TORONTO 28 29 11. Regent Park Learning Centre 12. Regent Park Aquatic Centre ST. LAWRENCE FUTURE CN TOWER DEVELOPMENT NATURALIZED 28. East Harbour Development RIVER VALLEY 29. East Harbour Transit Hub PORTLANDS RESTAURANTS 30. Google Smart City 13. Frankie’s Italian 14. Barrio Cerveceria HOSPITALS CITY TRANSIT LINES 15. Impact Kitchen 16. Cluny Bistro & Boulangerie EXISTING SUBWAY LINE FUTURE RELIEF LINE CHERRY BEACH 17. Mengrai Thai 31.