Rethinking Toronto's Middle Landscape: Spaces of Planning, Contestation, and Negotiation Robert Scott Fiedler a Dissertation S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Dog Off-Leash Area in Lawren Harris Square

City of Toronto – Parks, Forestry & Recreation Proposed Dog Off-Leash Area in Lawren Harris Square Survey Summary Report May 16, 2021 Rajesh Sankat, Senior Public Consultation Coordinator Alex Lavasidis, Senior Public Consultation Coordinator 1 Contents Project Background .................................................................................................................... 3 Survey Objectives ...................................................................................................................... 5 Notification ................................................................................................................................. 5 Key Feedback Summary ............................................................................................................ 5 Next Steps ................................................................................................................................. 4 Appendix A: Quantitative Response Summary ........................................................................... 5 Appendix B: Location ................................................................................................................. 7 Appendix C: Text Responses ..................................................................................................... 8 Appendix D: Email Responses ..................................................................................................66 2 Project Background Based on high demand from local residents, the City is considering the installation -

From Next Best to World Class: the People and Events That Have

FROM NEXT BEST TO WORLD CLASS The People and Events That Have Shaped the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation 1967–2017 C. Ian Kyer FROM NEXT BEST TO WORLD CLASS CDIC—Next Best to World Class.indb 1 02/10/2017 3:08:10 PM Other Historical Books by This Author A Thirty Years’ War: The Failed Public Private Partnership that Spurred the Creation of the Toronto Transit Commission, 1891–1921 (Osgoode Society and Irwin Law, Toronto, 2015) Lawyers, Families, and Businesses: A Social History of a Bay Street Law Firm, Faskens 1863–1963 (Osgoode Society and Irwin Law, Toronto, 2013) Damaging Winds: Rumours That Salieri Murdered Mozart Swirl in the Vienna of Beethoven and Schubert (historical novel published as an ebook through the National Arts Centre and the Canadian Opera Company, 2013) The Fiercest Debate: Cecil Wright, the Benchers, and Legal Education in Ontario, 1923–1957 (Osgoode Society and University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1987) with Jerome Bickenbach CDIC—Next Best to World Class.indb 2 02/10/2017 3:08:10 PM FROM NEXT BEST TO WORLD CLASS The People and Events That Have Shaped the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation 1967–2017 C. Ian Kyer CDIC—Next Best to World Class.indb 3 02/10/2017 3:08:10 PM Next Best to World Class: The People and Events That Have Shaped the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation, 1967–2017 © Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC), 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Target Finalizes Real Estate Transaction with Selection of 84 Additional Zellers Leases

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contacts: Amy Reilly, Target Communications, (612) 761-6782 Target Media Hotline, (612) 696-3400 John Hulbert, Investor Relations, (612) 761-6627 Target Finalizes Real Estate Transaction with Selection of 84 Additional Zellers Leases MINNEAPOLIS (Sept. 23, 2011) — Target Corporation (NYSE: TGT) is pleased to announce today that it has finalized its real estate transaction with Zellers Inc. with the selection of 84 additional Zellers leases, bringing the total number of leases selected, including an initial group of 105 leases selected in May, to 189. From this second group, Target has acquired the leasehold interests for 29 locations, the vast majority of which will open as Target stores beginning in 2013. The remaining leases have been or will be sold to other Canadian retailers or back to landlords. “Target is excited to take another meaningful step toward our expansion in Canada,” said Tony Fisher, president, Target Canada. “We look forward to delivering a superior shopping experience for our guests throughout Canada and building on our strong reputation as a good neighbor and partner in the communities in which we do business.” Target announced in January that it would purchase, for C$1.825 billion, the leasehold interests of up to 220 sites currently operated by Zellers Inc., a subsidiary of Hudson’s Bay Company. In May, Target selected an initial group of 105 leases, spanning all 10 provinces, in conjunction with its first payment to Zellers Inc. The vast majority of those sites will become Target stores beginning in 2013. The 84 leases announced today are part of Target’s second and final selection, and include the 39 leases for which Target transferred the rights to Walmart, as announced in June. -

Tocouncil Scorecard October 2 2011

2011.EX1.5 2011.EX1.7 2011.EX1.8 2011.MM3.2 2011.CD1.9 2011.EX3.5 (M1) 2011.EX3.2 (M1) 2011.EX3.4 (M2.1) 2011.EX3.4 2011.CC6.1 2011.EX4.7(M8) 2011.GM2.16 (M2) 2011.EX4.10 2011.PW3.1 2011.MM8.6 2011.EX5.3 (M1a) 2011.PW3.5 (M1) 2011.EX6.5 2011.PW5.1 (M7a) 2011.MM10.9 2011.EX9.6 2011.PW7.9 (M2) 2011.EX10.1 (M3a) 2011.EX10.1 (M3b) 2011.EX10.1 (M6e) 2011.EX10.1 (M7a) 2011.EX10.1 (M11) 2011.EX10.1 (M16a) 2011.EX10.1 (2b) 2011.EX10.1 (7) Reduce Eliminate Make TTC an Freeze Council Don't Condemn Freeze Eliminate Water Close the Eliminate Dissolve Reduce Rescind Conduct Move forward Kill the Fort Eliminate the Use less Approve sale of Eliminate Bike Uphold decision Revitalization of Review the Consider Eliminate the Eliminate the Eliminate Stop funding Consider Look at Extend timeline to Councillor Fed. Cuts to Property Taxes Efficiency "Ford Nation" Councillor Vehicle Essential Salaries Urban Affairs $75,000 from TCHC Board; number of previous ban extensive with process York Aboriginal environmentally- 22 TCHC single- Lanes on Jarvis to reject two Lower Don Scramble privatization of the Neighbourhood Toronto Youth Community the Christmas eliminating the outsourcing city- achieve city's tree Expense Registration Service Immigration for 2011 (no Rebate Library the Tenant replace with councillors on sale of service Percentage for contracting Pedestrian/Cy Affairs friendly treatment family homes Street1 provincially- Lands & Port Intersection at Toronto Parking Realm Cabinet & Seniors Environment Days Bureau Hardship Fund owned theatres canopy goals -

Court File No. CV-15-10832-00CL ONTARIO

Court File No. CV-15-10832-00CLCV-l5-10832-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OFOF' JUSTICE [COMMERCIALICOMMERCTAL LIST]LrSTI IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES' CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c.C-36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OFOF A PLANPLAN OFOF'COMPROMISE COMPROMISE AND ARRANGEMENT OFOF' TARGET CANADA CO., TARGET CANADACANADA HEALTH CO., TARGET CANADA MOBILE GP CO., TARGET CANADACANADA PHARMACYPHARMACY (BC)(BC) CORP.,CORP., TARGETTARGET CANADACANADA PHARMACY (ONTARIO) CORP.,CORP., TARGETTARGET CANADACANADA PHARMACY CORP.,CORP., TARGETTARGET CANADA PHARMACY (SK)(sK) CORP.,coRP., and TARGET CANADA PROPERTY LLCLLc Applicants RESPONDING MOTION RECORD OF FAUBOURGF'AUBOURG BOISBRIAND SHOPPING CENTRE HOLDINGS INC. (Motion to Accept Filing ofof aa Plan andand Authorize Creditors'Creditorso MeetingMeeting toto VoteVote onon thethe Plan) (Returnable(Returnable DecemberDecemb er 21, 2015)201 5) Date: December 8,8,2015 2015 DE GRANDPRÉ CHAIT LLP Lawyers 10001000 DeDe.La La Gauchetière Street West Suite 2900 Montréal (Québec) H3B 4W5 Telephone: 514514 878-431187 8-4311 Fax:Fax:514 514 878-4333878-4333 Stephen M. Raicek [email protected]@,dgclex.com Matthew Maloley mmalole)¡@declex.commmaroleyedgclex.com Lawyers for FaubourgFaubourg Boisbriand Boisbriand Shopping Shopping Centre Holdings Inc. TO: SERVICE LIST CCAA Proceedings ofof TargetTarget CanadaCanada Co.etCo.et al,al, CourtCourt File No. CV-15-10832-00CLCV-l5-10832-00CL Main Service List (as(as atatDecember7,2015) December 7, 2015) PARTY CONTACTcqNTACT • OSLER,osLER, HOSKIN & HARCOURT -

The Politicization of the Scarborough Rapid Transit Line in Post-Suburban Toronto

THE ‘TOONERVILLE TROLLEY’: THE POLITICIZATION OF THE SCARBOROUGH RAPID TRANSIT LINE IN POST-SUBURBAN TORONTO Peter Voltsinis 1 “The world is watching.”1 A spokesperson for the Province of Ontario’s (the Province) Urban Transportation Development Corporation (UTDC) uttered those poignant words on March 21, 1985, one day before the Toronto Transit Commission’s (TTC) inaugural opening of the Scarborough Rapid Transit (SRT) line.2 One day later, Ontario Deputy Premier Robert Welch gave the signal to the TTC dispatchers to send the line’s first trains into the Scarborough Town Centre Station, proclaiming that it was “a great day for Scarborough and a great day for public transit.”3 For him, the SRT was proof that Ontario can challenge the world.4 This research essay outlines the development of the SRT to carve out an accurate place for the infrastructure project in Toronto’s planning history. I focus on the SRT’s development chronology, from the moment of the Spadina Expressway’s cancellation in 1971 to the opening of the line in 1985. Correctly classifying what the SRT represents in Toronto’s planning history requires a clear vision of how the project emerged. To create that image, I first situate my research within Toronto’s dominant historiographical planning narratives. I then synthesize the processes and phenomena, specifically postmodern planning and post-suburbanization, that generated public transit alternatives to expressway development in Toronto in the 1970s. Building on my synthesis, I present how the SRT fits into that context and analyze the changing landscape of Toronto land-use politics in the 1970s and early-1980s. -

Summary by Quartile.Xlsx

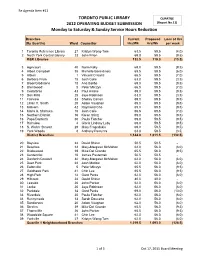

Re Agenda Item #11 TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARY QUARTILE 2012 OPERATING BUDGET SUBMISSION (Report No.11) Monday to Saturday & Sunday Service Hours Reduction Branches Current Proposed Loss of Hrs (By Quartile) Ward Councillor Hrs/Wk Hrs/Wk per week 1 Toronto Reference Library 27 Kristyn Wong-Tam 63.5 59.5 (4.0) 2 North York Central Library 23 John Filion 69.0 59.5 (9.5) R&R Libraries 132.5 119.0 (13.5) 3 Agincourt 40 Norm Kelly 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 4 Albert Campbell 35 Michelle Berardinetti 65.5 59.5 (6.0) 5 Albion 1 Vincent Crisanti 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 6 Barbara Frum 15 Josh Colle 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 7 Bloor/Gladstone 18 Ana Bailão 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 8 Brentwood 5 Peter Milczyn 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 9 Cedarbrae 43 Paul Ainslie 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 10 Don Mills 25 Jaye Robinson 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 11 Fairview 33 Shelley Carroll 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 12 Lillian H. Smith 20 Adam Vaughan 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 13 Malvern 42 Raymond Cho 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 14 Maria A. Shchuka 15 Josh Colle 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 15 Northern District 16 Karen Stintz 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 16 Pape/Danforth 30 Paula Fletcher 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 17 Richview 4 Gloria Lindsay Luby 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 18 S. Walter Stewart 29 Mary Fragedakis 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 19 York Woods 8 AAnthonynthony Perruzza 63.0 59.5 ((3.5)3.5) District Branches 1,144.0 1,011.5 (132.5) 20 Bayview 24 David Shiner 50.5 50.5 - 21 Beaches 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 22 Bridlewood 39 Mike Del Grande 65.5 56.0 (9.5) 23 Centennial 10 James Pasternak 50.5 50.5 - 24 Danforth/Coxwell 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 25 Deer Park 22 Josh Matlow 62.0 56.0 (6.0) -

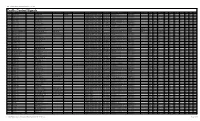

Traffic Control Signals As of July 4, 2017 Traffic Control Signals TCS# Main Midblock Side 1 Route Side 2 Route Add

TCS - Listing of Traffic Control Signals as of July 4, 2017 Traffic Control Signals TCS# Main Midblock Side 1 Route Side 2 Route Add. Info. Private Access District Cabinet Controller Model System SCOOT No. MOC FDW APS WRM PE_TP PE_FH PE_RL MTO LED PCS 0002 JARVIS ST FRONT ST E LOWER TORONTO AND EAST YORK TS2 Type1 PEEK ATC - 1000 TransSuite FXT Yes No No No No No No Yes Yes 0003 KING ST E JARVIS ST TORONTO AND EAST YORK TS2 Type1 PEEK ATC - 1000 TransSuite FXT Yes No No Yes No No No Yes Yes 0004 JARVIS ST ADELAIDE ST E TORONTO AND EAST YORK TS2 Type1 ECONOLITE ASC/3 - 2100 TransSuite FXT Yes No No No No No No Yes Yes 0005 JARVIS ST RICHMOND ST E TORONTO AND EAST YORK TS2 Type1 ECONOLITE ASC/3 - 2100 TransSuite FXT Yes No No No No No No Yes Yes 0006 JARVIS ST QUEEN ST E TORONTO AND EAST YORK TS2 Type1 ECONOLITE ASC/3 - 2100 TransSuite FXT Yes No No No No No No Yes Yes 0007 JARVIS ST SHUTER ST TORONTO AND EAST YORK TS2 Type1 ECONOLITE ASC/3 - 2100 TransSuite FXT Yes No No No No No No Yes Yes 0008 JARVIS ST DUNDAS ST E TORONTO AND EAST YORK TS2 Type1 PEEK ATC - 1000 TransSuite FXT Yes Yes No No No No No Yes Yes 0009 JARVIS ST GERRARD ST E TORONTO AND EAST YORK TS2 Type1 ECONOLITE ASC/3 - 2100 TransSuite FXT Yes No No No No No No Yes Yes 0010 JARVIS ST CARLTON ST TORONTO AND EAST YORK TS2 Type1 ECONOLITE ASC/3 - 2100 TransSuite FXT Yes Yes No No No No No Yes Yes 0011 JARVIS ST WELLESLEY ST E TORONTO AND EAST YORK CA NOVAX 18 CCT SCOOT 23311 FXT Yes No No No No No No Yes Yes 0012 JARVIS ST ISABELLA ST TORONTO AND EAST YORK CA LS 180 SCOOT 23421 -

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25 http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2013.MM... Item Tracking Status City Council adopted this item on November 13, 2013 with amendments. City Council consideration on November 13, 2013 MM41.25 ACTION Amended Ward:All Requesting Mayor Ford to respond to recent events - by Councillor Denzil Minnan-Wong, seconded by Councillor Peter Milczyn City Council Decision Caution: This is a preliminary decision. This decision should not be considered final until the meeting is complete and the City Clerk has confirmed the decisions for this meeting. City Council on November 13 and 14, 2013, adopted the following: 1. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for misleading the City of Toronto as to the existence of a video in which he appears to be involved in the use of drugs. 2. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to co-operate fully with the Toronto Police in their investigation of these matters by meeting with them in order to respond to questions arising from their investigation. 3. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for writing a letter of reference for Alexander "Sandro" Lisi, an alleged drug dealer, on City of Toronto Mayor letterhead. 4. City Council request Mayor Ford to answer to Members of Council on the aforementioned subjects directly and not through the media. 5. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to take a temporary leave of absence to address his personal issues, then return to lead the City in the capacity for which he was elected. 6. City Council request the Integrity Commissioner to report back to City Council on the concerns raised in Part 1 through 5 above in regard to the Councillors' Code of Conduct. -

5 Important Reasons to Join BVA!

Membership 5 Important Reasons to join BVA! Over the years, many of the resident members of the Bayview Village Association (“BVA”) have shared stories with the Association leadership about how they bought their first home in spring 2014. They had saved long and hard to move into an “established” neighbourhood with great schools and ample parkland with vast ravines to walk their pets. You would be amazed at how much research buyers and new entrants into our neighbourhood do beforehand — checking out crime watch and open blogs, drove by at different times of the day and, of course, chatted with the neighbours. Our newer residents state that, most often, the neighbours really sealed the deal for them. “We were moving into a neighbourhood with a highly active and energized neighbourhood association. We signed the last piece of paperwork and immediately jumped into all things neighbourly, and that included joining our neighbourhood association”. If you think these associations aren’t for you, or you are unsure on how you can contribute to your own neighbourhood, I urge you to think about the following: 1. Good Neighbours Equal Good Neighbourhoods When you gather a group of people interested in bettering their neighbourhood, I am pretty confident good things will come your way. While most neighbours are interested in preventing crime, some are interested in clean public parks and open areas or more street lighting. All of these personal agendas make for a diverse to-do list. When it becomes personal, the vested interest grows stronger within the group. “The neighbourhood BVA is that ‘just right’ level of engagement — large enough to take me outside of my individual concerns but small enough to really get to know people and tackle issues head on,” says a current Bayview Village owner/resident. -

Toronto City Council Enviro Report Card 2010-2014

TORONTO CITY COUNCIL ENVIRO REPORT CARD 2010-2014 TORONTO ENVIRONMENTAL ALLIANCE • JUNE 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY hortly after the 2010 municipal election, TEA released a report noting that a majority of elected SCouncillors had committed to building a greener city. We were right but not in the way we expected to be. Councillors showed their commitment by protecting important green programs and services from being cut and had to put building a greener city on hold. We had hoped the 2010-14 term of City Council would lead to significant advancement of 6 priority green actions TEA had outlined as crucial to building a greener city. Sadly, we’ve seen little - if any - advancement in these actions. This is because much of the last 4 years has been spent by a slim majority of Councillors defending existing environmental policies and services from being cut or eliminated by the Mayor and his supporters; programs such as Community Environment Days, TTC service and tree canopy maintenance. Only in rare instances was Council proactive. For example, taking the next steps to grow the Greenbelt into Toronto; calling for an environmental assessment of Line 9. This report card does not evaluate individual Council members on their collective inaction in meeting the 2010 priorities because it is almost impossible to objectively grade individual Council members on this. Rather, it evaluates Council members on how they voted on key environmental issues. The results are interesting: • Average Grade: C+ • The Mayor failed and had the worst score. • 17 Councillors got A+ • 16 Councillors got F • 9 Councillors got between A and D In the end, the 2010-14 Council term can be best described as a battle between those who wanted to preserve green programs and those who wanted to dismantle them. -

Gentrification Reconsidered: the Case of the Junction

Gentrification Reconsidered: The Case of The Junction By: Anthony Ruggiero Submitted: July 31th, 2014 A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies (Urban Planning) Faculty of Environmental Studies York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada __________________________ ___________________________ Anthony Ruggiero John Saunders, PhD MES Candidate Supervisor ii Abstract This paper examines the factors responsible for the gentrification of The Junction, a west-end neighbourhood located on the edge of downtown Toronto. After years of neglect, degradation and deindustrialization, The Junction is currently in the midst of being gentrified. Through various forms of neighbourhood upgrading and displacement, gentrification has been responsible for turning a number working-class Toronto neighbourhoods into middle-class enclaves. The Junction is unique in this regard because it does not conform to past theoretical perspectives regarding gentrification in Toronto. Through the use of an instrumental case-study, various factors responsible for The Junction’s gentrification are examined and a number of its indicators that are present in the neighbourhood are explored so that a solid understanding regarding the neighbourhood’s gentrification can be realized. What emerges is a form of ‘user-friendly’ or ‘community-driven’ gentrification that places emphasis on neighbourhood revitalization and community inclusion, as opposed to resident displacement