Public Project, Private Developer: Understanding the Impact of Local

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Dog Off-Leash Area in Lawren Harris Square

City of Toronto – Parks, Forestry & Recreation Proposed Dog Off-Leash Area in Lawren Harris Square Survey Summary Report May 16, 2021 Rajesh Sankat, Senior Public Consultation Coordinator Alex Lavasidis, Senior Public Consultation Coordinator 1 Contents Project Background .................................................................................................................... 3 Survey Objectives ...................................................................................................................... 5 Notification ................................................................................................................................. 5 Key Feedback Summary ............................................................................................................ 5 Next Steps ................................................................................................................................. 4 Appendix A: Quantitative Response Summary ........................................................................... 5 Appendix B: Location ................................................................................................................. 7 Appendix C: Text Responses ..................................................................................................... 8 Appendix D: Email Responses ..................................................................................................66 2 Project Background Based on high demand from local residents, the City is considering the installation -

Volume 5 Has Been Updated to Reflect the Specific Additions/Revisions Outlined in the Errata to the Environmental Project Report, Dated November, 2017

DISCLAIMER AND LIMITATION OF LIABILITY This Revised Final Environmental Project Report – Volume 5 has been updated to reflect the specific additions/revisions outlined in the Errata to the Environmental Project Report, dated November, 2017. As such, it supersedes the previous Final version dated October, 2017. The report dated October, 2017 (“Report”), which includes its text, tables, figures and appendices) has been prepared by Gannett Fleming Canada ULC (“Gannett Fleming”) and Morrison Hershfield Limited (“Morrison Hershfield”) (“Consultants”) for the exclusive use of Metrolinx. Consultants disclaim any liability or responsibility to any person or party other than Metrolinx for loss, damage, expense, fines, costs or penalties arising from or in connection with the Report or its use or reliance on any information, opinion, advice, conclusion or recommendation contained in it. To the extent permitted by law, Consultants also excludes all implied or statutory warranties and conditions. In preparing the Report, the Consultants have relied in good faith on information provided by third party agencies, individuals and companies as noted in the Report. The Consultants have assumed that this information is factual and accurate and has not independently verified such information except as required by the standard of care. The Consultants accept no responsibility or liability for errors or omissions that are the result of any deficiencies in such information. The opinions, advice, conclusions and recommendations in the Report are valid as of the date of the Report and are based on the data and information collected by the Consultants during their investigations as set out in the Report. The opinions, advice, conclusions and recommendations in the Report are based on the conditions encountered by the Consultants at the site(s) at the time of their investigations, supplemented by historical information and data obtained as described in the Report. -

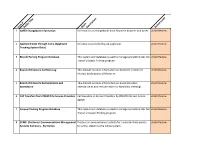

2020 Open Data Inventory

le n it tio T ip lic t r b s c u or e Item # P Sh D Access Level 1 AMEX Chargeback Information Information on chargebacks from Payment Acquirer and Amex Under Review 2 Applicant Data Through Taleo (Applicant Information provided by job applicants Under Review Tracking System Data) 3 Bicycle Parking Program Database This system and database is used to manage and administer GO Under Review Transit's Bicycle Parking program 4 Board of Directors Conflicts Log This dataset contains information on Directors' conflict of Under Review interest declarations at Metrolinx 5 Board of Directors Remuneration and This dataset contains information on Board Directors' Under Review Attendance attendance at and remuneration for Metrolinx meetings 6 Call Transfers from PRESTO to Service Providers Call transfers to Service Providers by PRESTO Contact Centre Under Review Agents 7 Carpool Parking Program Database This system and database is used to manage and administer GO Under Review Transit's Carpool Parking program 8 CCMS (Customer Communications Management Displays all announcement activity for a selected time period Under Review System) Summary - By Station for a line, station or the whole system. 9 CCMS (Customer Communications Management Displays number of messages (total) sent to each customer Under Review System) Summary by Channel channel over a time period. 10 CCMS (Customer Communications Management Displays all messages sent through CCMS for selected time Under Review System) Summary period. Shows what we sent as well as where it was sent and -

Rethinking Toronto's Middle Landscape: Spaces of Planning, Contestation, and Negotiation Robert Scott Fiedler a Dissertation S

RETHINKING TORONTO’S MIDDLE LANDSCAPE: SPACES OF PLANNING, CONTESTATION, AND NEGOTIATION ROBERT SCOTT FIEDLER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GEOGRAPHY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO May 2017 © Robert Scott Fiedler, 2017 Abstract This dissertation weaves together an examination of the concept and meanings of suburb and suburban, historical geographies of suburbs and suburbanization, and a detailed focus on Scarborough as a suburban space within Toronto in order to better understand postwar suburbanization and suburban change as it played out in a specific metropolitan context and locale. With Canada and the United States now thought to be suburban nations, critical suburban histories and studies of suburban problems are an important contribution to urbanistic discourse and human geographical scholarship. Though suburbanization is a global phenomenon and suburbs have a much longer history, the vast scale and explosive pace of suburban development after the Second World War has a powerful influence on how “suburb” and “suburban” are represented and understood. One powerful socio-spatial imaginary is evident in discourses on planning and politics in Toronto: the city-suburb or urban-suburban divide. An important contribution of this dissertation is to trace out how the city-suburban divide and meanings attached to “city” and “suburb” have been integral to the planning and politics that have shaped and continue to shape Scarborough and Toronto. The research employs an investigative approach influenced by Michel Foucault’s critical and effective histories and Bent Flyvbjerg’s methodological guidelines for phronetic social science. -

Land Use Study: Development in Proximity to Rail Operations

Phase 1 Interim Report Land Use Study: Development in Proximity to Rail Operations City of Toronto Prepared for the City of Toronto by IBI Group and Stantec August 30, 2017 IBI GROUP PHASE 1 INTERIM REPORT LAND USE STUDY: DEVELOPMENT IN PROXIMITY TO RAIL OPERATIONS Prepared for City of Toronto Document Control Page CLIENT: City of Toronto City-Wide Land Use Study: Development in Proximity to Rail PROJECT NAME: Operations Land Use Study: Development in Proximity to Rail Operations REPORT TITLE: Phase 1 Interim Report - DRAFT IBI REFERENCE: 105734 VERSION: V2 - Issued August 30, 2017 J:\105734_RailProximit\10.0 Reports\Phase 1 - Data DIGITAL MASTER: Collection\Task 3 - Interim Report for Phase 1\TTR_CityWideLandUse_Phase1InterimReport_2017-08-30.docx ORIGINATOR: Patrick Garel REVIEWER: Margaret Parkhill, Steve Donald AUTHORIZATION: Lee Sims CIRCULATION LIST: HISTORY: Accessibility This document, as of the date of issuance, is provided in a format compatible with the requirements of the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA), 2005. August 30, 2017 IBI GROUP PHASE 1 INTERIM REPORT LAND USE STUDY: DEVELOPMENT IN PROXIMITY TO RAIL OPERATIONS Prepared for City of Toronto Table of Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of Study ..................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Background ............................................................................................................. -

Cultural Heritage Screen Report

Lincolnville Go Station Improvements: Cultural Heritage Screening Report Prepared for: Metrolinx 20 Bay Street, Suite 1800 Toronto ON M5J 2W3 ~ METROLINX Prepared by: Stantec Consulting Ltd. 300W-675 Cochrane Drive Markham ON L3R 0B8 () Stantec File No. 1135200010 October 12, 2017 LINCOLNVILLE GO STATION IMPROVEMENTS: CULTURAL HERITAGE SCREENING REPORT Project Personnel EA Project Manager: Alex Blasko, B.Sc. (Hon.) Heritage Consultant: Heidy Schopf, MES, CAHP Task Manager: Meaghan Rivard, MA, CAHP Report Writer: Heidy Schopf, MES, CAHP Laura Walter, MA GIS Specialist: Sean Earles Office Assistants: Carol Naylor Quality Review: Meaghan Rivard, MA, CAHP Independent Review: Tracie Carmichael, BA, B. Ed. () Stantec Sign-off Sheet This document was prepared by Stantec Consulting Ltd. (“Stantec”) for the account of Metrolinx (the “Client”). The material in it reflects Stantec’s professional judgment in light of the scope, schedule and other limitations stated in the document and in the contract between Stantec and the Client. The opinions in the document are based on conditions and information existing at the time the document was published and do not take into account any subsequent changes. The report has been prepared based, in part, on information provided by others as cited in the Reference section. Stantec has not verified the accuracy and / or completeness of third party information. Prepared by (signature) Heidy Schopf, MES, CAHP Cultural Heritage Specialist Reviewed by (signature) Signed by Tracie Carmichael on behalf of: Meaghan Rivard, -

Exhibition Place Master Plan – Phase 1 Proposals Report

Acknowledgments The site of Exhibition Place has had a long tradition as a gathering place. Given its location on the water, these lands would have attracted Indigenous populations before recorded history. We acknowledge that the land occupied by Exhibition Place is the traditional territory of many nations including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples and is now home to many diverse First Nations, Inuit and Metis peoples. We also acknowledge that Toronto is covered by Treaty 13 with the Mississaugas of the Credit, and the Williams Treaties signed with multiple Mississaugas and Chippewa bands. Figure 1. Moccasin Identifier engraving at Toronto Trillium Park The study team would like to thank City Planning Division Study Team Exhibition Place Lynda Macdonald, Director Don Boyle, Chief Executive Officer Nasim Adab Gilles Bouchard Tamara Anson-Cartwright Catherine de Nobriga Juliana Azem Ribeiro de Almeida Mark Goss Bryan Bowen Hardat Persaud David Brutto Tony Porter Brent Fairbairn Laura Purdy Christian Giles Debbie Sanderson Kevin Lee Kelvin Seow Liz McFarland Svetlana Lavrentieva Board of Governors Melanie Melnyk Tenants, Clients and Operators Dan Nicholson James Parakh David Stonehouse Brad Sunderland Nigel Tahair Alison Torrie-Lapaire 4 - PHASE 1 PROPOSALS REPORT FOR EXHIBITION PLACE Local Advisory Committee Technical Advisory Committee Bathurst Quay Neighbourhood Association Michelle Berquist - Transportation Planning The Bentway Swinzle Chauhan – Transportation Services -

PRESTO Update – TTC/Metrolinx Settlement

2053.2 For Action with Confidential Attachment PRESTO Update – TTC/Metrolinx Settlement Date: May 12, 2021 To: TTC Board From: Chief Strategy and Customer Officer Reason for Confidential Information This reports contains information that is subject to solicitor-client privilege. This report is about litigation or potential litigation, including matters before administrative tribunals. This report contains information relating to a position, plan, procedure, criteria or instruction to be applied to any negotiations carried on or to be carried on by the TTC. Summary The purpose of this report is to provide an update on the progress made since the last TTC/Metrolinx PRESTO Settlement update in February 2021. This includes: . an update on the results of the Settlement and Arbitration for the current PRESTO contract with Metrolinx. Recommendations It is recommended that: 1. The TTC Board receive this report for information; and 2. The information in the Confidential Attachment remain confidential as it is subject to solicitor-client privilege. Financial Summary There are no financial implications arising from this report. The Interim Chief Financial Officer has reviewed this report and agrees with the financial impact information. PRESTO UPDATE: TTC/Metrolinx Settlement Page 1 of 5 Equity/Accessibility Matters As progress is being made through negotiations with PRESTO on closing out contract items and planning for the future, equity and accessibility continues to be imperative. The TTC is committed to meeting the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) requirements through continuing consultations with the Advisory Committee on Accessible Transit (ACAT), and introducing policies that promote equity and accessibility. Decision History At its meeting of June 12, 2019, the TTC Board received a comprehensive implementation update on PRESTO. -

Gentrification Reconsidered: the Case of the Junction

Gentrification Reconsidered: The Case of The Junction By: Anthony Ruggiero Submitted: July 31th, 2014 A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies (Urban Planning) Faculty of Environmental Studies York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada __________________________ ___________________________ Anthony Ruggiero John Saunders, PhD MES Candidate Supervisor ii Abstract This paper examines the factors responsible for the gentrification of The Junction, a west-end neighbourhood located on the edge of downtown Toronto. After years of neglect, degradation and deindustrialization, The Junction is currently in the midst of being gentrified. Through various forms of neighbourhood upgrading and displacement, gentrification has been responsible for turning a number working-class Toronto neighbourhoods into middle-class enclaves. The Junction is unique in this regard because it does not conform to past theoretical perspectives regarding gentrification in Toronto. Through the use of an instrumental case-study, various factors responsible for The Junction’s gentrification are examined and a number of its indicators that are present in the neighbourhood are explored so that a solid understanding regarding the neighbourhood’s gentrification can be realized. What emerges is a form of ‘user-friendly’ or ‘community-driven’ gentrification that places emphasis on neighbourhood revitalization and community inclusion, as opposed to resident displacement -

923466Magazine1final

www.globalvillagefestival.ca Global Village Festival 2015 Publisher: Silk Road Publishing Founder: Steve Moghadam General Manager: Elly Achack Production Manager: Bahareh Nouri Team: Mike Mahmoudian, Sheri Chahidi, Parviz Achak, Eva Okati, Alexander Fairlie Jennifer Berry, Tony Berry Phone: 416-500-0007 Email: offi[email protected] Web: www.GlobalVillageFestival.ca Front Cover Photo Credit: © Kone | Dreamstime.com - Toronto Skyline At Night Photo Contents 08 Greater Toronto Area 49 Recreation in Toronto 78 Toronto sports 11 History of Toronto 51 Transportation in Toronto 88 List of sports teams in Toronto 16 Municipal government of Toronto 56 Public transportation in Toronto 90 List of museums in Toronto 19 Geography of Toronto 58 Economy of Toronto 92 Hotels in Toronto 22 History of neighbourhoods in Toronto 61 Toronto Purchase 94 List of neighbourhoods in Toronto 26 Demographics of Toronto 62 Public services in Toronto 97 List of Toronto parks 31 Architecture of Toronto 63 Lake Ontario 99 List of shopping malls in Toronto 36 Culture in Toronto 67 York, Upper Canada 42 Tourism in Toronto 71 Sister cities of Toronto 45 Education in Toronto 73 Annual events in Toronto 48 Health in Toronto 74 Media in Toronto 3 www.globalvillagefestival.ca The Hon. Yonah Martin SENATE SÉNAT L’hon Yonah Martin CANADA August 2015 The Senate of Canada Le Sénat du Canada Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4 K1A 0A4 August 8, 2015 Greetings from the Honourable Yonah Martin Greetings from Senator Victor Oh On behalf of the Senate of Canada, sincere greetings to all of the organizers and participants of the I am pleased to extend my warmest greetings to everyone attending the 2015 North York 2015 North York Festival. -

Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA)

APPENDIX M Heritage Impact Assessment – Union Station Trainshed Heritage impact assessment Union Station Trainshed GO Rail Network Electrification Project Environmental Assessment Project # 14-087-18 Prepared by GS/JN PREPARED FOR: Rodney Yee, Project Coordinator Environmental Programs & Assessment Metrolinx 20 Bay Street Toronto, ON M5J 2W3 416-202-4516 [email protected] PREPARED BY: ERA Architects Inc. 10 St. Mary Street, Suite 801 Toronto, ON M4Y 1P9 416-963-4497 Issued: 2017-01-16 Reissued: 2017-09-18 Cover Image: Union Station Trainshed, 1930. Source: Toronto Archives CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Scope of the Report 1.2 Property Description 1.3 Site History 2 Methodology 11 2.1 Summary of Related Policy/Legislation/Guidelines 2.2 Material Reviewed 2.3 Date of Site Visit 3 Discussion of Cultural Heritage Value and Status 14 3.1 Discussion of Cultural Heritage Value 3.2 Statement of Cultural Heritage Value 3.3 Heritage Recognition 4 Site conditions 20 4.1 Current Conditions 5 Discussion of the Proposed Intervention 25 5.1 Description of Proposed Interventions 5.2 Impact Assessment 5.3 Mitigation Strategies 6 Conclusion 34 6.1 General 6.2 Revitalization Context 7 Sources 35 8 Appendix 36 Appendix 1 - Union Station Designation By-law (City of Toronto By-law 948-2005) Appendix 2 - Heritage Easement Agreement between The Toronto Terminals Railway Company Limited and the City of Toronto dated June 30, 2000 Appendix 3 - Heritage Character Statement, 1989 Appendix 4 - Commemorative Integrity Statement, 2000 Reissued: 18 September 2017 i ExEcutivE Summary This Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) revises the HIA dated January 16, 2017 in order to evaluate the impact of proposed work on existing resources at the subject site, based on an established understanding of their heritage value and attributes derived from the Heritage Statement Report - Union Station Complex, completed by Taylor Hazell Architects in June 2016 and the Union Station Trainshed Heritage Impact Assessment by Taylor Hazell Architects from July 2005. -

Suburban Growth in the Toronto CMA, 1996-2016: a Case of Johnny Town-Mouse and Timmy Willie

Suburban growth in the Toronto CMA, 1996-2016: A Case of Johnny Town-Mouse and Timmy Willie Chris Willms A Master’s Report submitted to the School of Urban and Regional Planning in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Urban and Regional Planning School of Urban and Regional Planning Department of Geography and Planning Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada December 2018 Copyright © Chris Willms, 2018 Suburban growth in the Toronto CMA, 1996-2016: A Case of Johnny Town-Mouse and Timmy Willie Chris Willms, 2018 Executive Summary This report addressed the following questions: 1. What proportion of Toronto residents live in suburbs, and what is their distribution? 2. How has this proportion and distribution changed over time? 3. Are local growth management policies achieving their targets and objectives in Toronto? Methods To help answer these questions, proven methods to describe population distribution were employed using data from the Statistics Canada Census for 2016, 2006 and 1996. The results classified all 1,151 census tracts in the Toronto Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) as either active core, transit suburb, auto suburb, or exurb. Each census tract is approximately 4,000 to 8,000 people, with boundaries that are stable and define recognizable neighbourhoods. Active cores and transit suburbs were generally considered to be locations of more sustainable development. In these locations, higher proportions of commuters walked, cycled, or used some form of transit. Auto suburbs and exurbs were generally considered to be locations of less sustainable development. In these locations, higher proportions of commuters drove personal vehicles and population densities were lower.