Kinsey Et Al. School Closures During Covid.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student/Parent Handbook 2017-2018

535 Locust Street P.O. Box 325 Sidman, PA 15955 (814) 487-7613 www.fhrangers.org STUDENT/PARENT HANDBOOK 2017-2018 Through the efforts of the Student Assistance Program, the high school administration, and others, this handbook has been prepared for you. Its purpose is to make you aware of the opportunities available to you and the rules and regulations that govern these opportunities. Any organization that is to function smoothly must have order. It is our hope that this book can be your guide to adjust to and participate in the high school program in a manner that will be both educationally enjoyable and profitable. THE MISSION OF THE FOREST HILLS SCHOOL DISTRICT IS TO PROVIDE THE BEST STUDENT-CENTERED EDUCATION IN AN ENVIRONMENT WHERE THE TRADITION IS EXCELLENCE. Nondiscriminatory Statement The Forest Hills School District does not discriminate in educational programs, activities or employment practices based on race, color, national origin, sex, disability, age, religion, ancestry or any other legally protected classification. This policy is in accordance with state and federal laws, including Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, Sections 503 and 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. This handbook belongs to: NAME______________________________________________ GRADE________ ACTIVITY ROOM__________ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS POLICIES AND PROCEDURES Ambulance Policy ...............................................................7 -

The “Dark Side” of Food Stuff Proteomics: the CPLL-Marshals Investigate

Foods 2014, 3, 217-237; doi:10.3390/foods3020217 OPEN ACCESS foods ISSN 2304-8158 www.mdpi.com/journal/foods Review The “Dark Side” of Food Stuff Proteomics: The CPLL-Marshals Investigate Pier Giorgio Righetti 1,*, Elisa Fasoli 1, Alfonsina D’Amato 1 and Egisto Boschetti 2 1 Department of Chemistry, Materials and Chemical Engineering “Giulio Natta”, Politecnico di Milano, Via Mancinelli 7, Milano 20131, Italy; E-Mails: [email protected] (E.F.); [email protected] (A.D.) 2 EB Consulting, Paris, France; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-022-399-3045; Fax: +39-022-399-3080. Received: 4 February 2014; in revised form: 8 April 2014 / Accepted: 8 April 2014 / Published: 17 April 2014 Abstract: The present review deals with analysis of the proteome of animal and plant-derived food stuff, as well as of non-alcoholic and alcoholic beverages. The survey is limited to those systems investigated with the help of combinatorial peptide ligand libraries, a most powerful technique allowing access to low- to very-low-abundance proteins, i.e., to those proteins that might characterize univocally a given biological system and, in the case of commercial food preparations, attest their genuineness or adulteration. Among animal foods the analysis of cow’s and donkey’s milk is reported, together with the proteomic composition of egg white and yolk, as well as of honey, considered as a hybrid between floral and animal origin. In terms of plant and fruits, a survey is offered of spinach, artichoke, banana, avocado, mango and lemon proteomics, considered as recalcitrant tissues in that small amounts of proteins are dispersed into a large body of plant polymers and metabolites. -

Academic Catalog 2012-2013

ACADEMIC CATALOG 2012-2013 2012-2013 Academic Catalog Lynn University is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools to award baccalaureate, master’s and doctoral degrees. Contact the Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call 404-679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Lynn University. Equal Opportunity Policy Lynn University is committed to and actively supports the spirit and the letter of equal opportunity as defined by federal, state and local laws. It is the policy of Lynn University to ensure equal opportunity in administration of its educational policies, admissions policies and employment policies without discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin, ancestry, citizenship, disability, pregnancy, genetic disposition, veteran or military status, marital status, familial status or any other legally protected characteristic in accordance with federal and Florida State law. Lynn University administers all human resource policies and practices, including recruitment, advertising, hiring, selection for training, compensation, promotion, discipline, and termination, without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin, ancestry, citizenship, disability, pregnancy, genetic disposition, veteran or military status, marital status, familial status or any other legally protected characteristic in accordance with federal and Florida State law. Please Be Advised: The contents of this catalog represent the most current information available at the time of publication. However, during the period of time covered by this catalog, it is reasonable to expect changes to be made with respect to this information without prior notice. The course offerings and requirements of Lynn University are under continual examination and revision. -

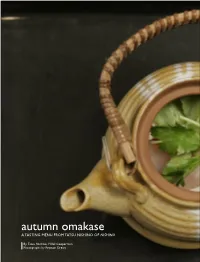

Autumn Omakase a TASTING MENU from TATSU NISHINO of NISHINO

autumn omakase A TASTING MENU FROM TATSU NISHINO OF NISHINO By Tatsu Nishino, Hillel Cooperman Photographs by Peyman Oreizy First published in 2005 by tastingmenu.publishing Seattle, WA www.tastingmenu.com/publishing/ Copyright © 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publisher. Photographs © tastingmenu and Peyman Oreizy Autumn Omakase By Tatsu Nishino, Hillel Cooperman, photographs by Peyman Oreizy The typeface family used throughout is Gill Sans designed by Eric Gill in 1929-30. TABLE OF CONTENTS Tatsu Nishino and Nishino by Hillel Cooperman Introduction by Tatsu Nishino Autumn Omakase 17 Oyster, Salmon, Scallop Appetizer 29 Kampachi Usuzukuri 39 Seared Foie Gras, Maguro, and Shiitake Mushroom with Red Wine Soy Reduction 53 Matsutake Dobinmushi 63 Dungeness Crab, Friseé, Arugula, and Fuyu Persimmon Salad with Sesame Vinaigrette 73 Hirame Tempura Stuffed with Uni, Truffle, and Shiso 85 Hamachi with Balsamic Teriyaki 95 Toro Sushi, Three Ways 107 Plum Wine Fruit Gratin The Making of Autumn Omakase Who Did What Invitation TATSU NISHINO AND NISHINO In the United States, ethnic cuisines generally fit into convenient and simplistic categories. Mexican food is one monolithic cuisine, as is Chinese, Italian, and of course Japanese. Every Japanese restaurant serves miso soup, various tempura items, teriyaki, sushi, etc. The fact that Japanese cuisine is multi-faceted (as are most cuisines) and quite diverse doesn’t generally come through to the public—the American homogenization machine reduces an entire culture’s culinary contributions to a simple formula that can fit on one menu. -

Champagne À Table: the Gastronomic Position Of

Food & Wine October 2015 International Wine & Food Society Europe & Africa Committee Free to European & African Zone Members - one per address - Issue 124 SAVOIE DECOUVERTE A GOURMET FIVE DAYS IN SAN SEBASTIAN Goldlocki Champagne à Table: The Gastronomic Position of Champagne throughout History CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE Dear Members I hope you enjoyed all your activities and trips during the last few months, and that your branch has a good forward pro- gramme, to keep you involved and busy. We are now in the cycle where you will receive alternately, every two months, a Food & Wine Online communication by email, and then a printed Food & Wine Magazine. I do hope you enjoyed the Online version we sent out at the end of August. Thanks to those who contributed and to Andrea Warren for putting it together. We stressed how important it is that we have your, up to date, email address, so you receive both the International ‗Grapevine‘ and ‗Food & Wine Online‘, and your home address to receive the magazine. You can check and update your email or home address by log- ging onto the www.iwfs.org website, clicking ‗My Account‘ at the top right hand corner, and then Member Details click (edit) or Primary Address Home click (edit). Don‘t forget to click ‗Save Changes‘ when you have made some! Alterna- tively contact your branch administrator to update your details. Some of you missed the email communication because it went from an unfamiliar address and ended up in your spam/ junk mail. Please check your spam filter settings, or for more certainty add this address ‗ International Secretary ‗ email [email protected] to your contacts or address list as a trusted sender/address. -

Questions and Answers Regarding Food Facility Registration (Seventh Edition): Guidance for Industry

Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Questions and Answers Regarding Food Facility Registration (Seventh Edition): Guidance for Industry You may submit electronic or written comments regarding this guidance at any time. Submit electronic comments to https://www.regulations.gov/. Submit written comments on the guidance to the Dockets Management Staff (HFA-305), Food and Drug Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852. All comments should be identified with the docket number FDA-2012-D-1002 listed in the notice of availability that publishes in the Federal Register. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Office of Foods and Veterinary Medicine Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition Center for Veterinary Medicine Office of Regulatory Affairs August 2018 1 Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 3 II. QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS ...................................................................................... 4 A. Who Must Register? .................................................................................................... 4 B. Who is Exempt from Registration? ........................................................................... 4 C. Definitions .................................................................................................................. 21 D. When Must You Register or Renew Your Registration? ..................................... -

COVID-19 Emergency Relief Resources For

COVID-19 Emergency Relief Resources for PDX (and beyond) -This list of resources was compiled and is being updated by Congressman Earl Blumenauer and his team in Portland, Oregon. Please share with your networks: www.earlblumenauer.com/coronavirus -If you have additional resources for consideration, please email us at [email protected]. -We have done our best to verify information, but things are changing at a rapid pace, so be sure to contact businesses for updates and verification before visiting. -In Oregon, call 211 from a cell phone, 503-222-5555 from a landline, text your zip code to 898211, or email [email protected] to find services and answer your questions about COVID-19. Name Area Served Support Offered Website Notes/Additional Info Food Access/Resources Type in zip code and access free groceries, meals, produce, and other programs in your area. Note: Food pantries and food assistance sites across the state remain open Note: Most pantries are still open, but this could change. Pantry services will with increased cleaning and changes in service to help minimize contact among large change. Many are moving to a box model to reduce social distancing. Call groups of people. Though hours of operation are updated as frequently as possible, pantries in advance if you are able to for more information. (verified/updated Oregon Food Bank Statewide Food Finder Oregon please call ahead before visiting a partner agency. https://www.oregonfoodbank.org/find-help/find-food/ 3/23/20) PPS, Centennial, David Douglas, Gresham-Barlow, School Food Access Sites Parkrose, Reynolds Food and meal distribution at local schools. -

2014-2015-Academic-Catalog.Pdf

ACADEMIC CATALOG 2014-2015 2014-2015 Academic Catalog Lynn University is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges to award baccalaureate, masters and doctoral degrees. Contact the Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call 404-679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Lynn University. Equal Opportunity Policy Lynn University is committed to and actively supports the spirit and the letter of equal opportunity as defined by federal, state and local laws. It is the policy of Lynn University to ensure equal opportunity in administration of its educational policies, admissions policies and employment policies without discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin, ancestry, citizenship, disability, pregnancy, genetic disposition, veteran or military status, marital status, familial status or any other legally protected characteristic in accordance with federal and Florida State law. Lynn University administers all human resource policies and practices, including recruitment, advertising, hiring, selection for training, compensation, promotion, discipline, and termination, without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin, ancestry, citizenship, disability, pregnancy, genetic disposition, veteran or military status, marital status, familial status or any other legally protected characteristic in accordance with federal and Florida State law. Please Be Advised: The contents of this catalog represent the most current information available at the time of publication. However, during the period of time covered by this catalog, it is reasonable to expect changes to be made with respect to this information without prior notice. The course offerings and requirements of Lynn University are under continual examination and revision. -

Food at Work

FOOD AT WORK WORKPLACE SOLUTIONS FOR MALNUTRITION, OBESITY AND CHRONIC DISEASES The author Christopher Wanjek is a freelance health and science writer based in the United States. He is a frequent contributor to The Washington Post and popular science magazines, and he is the author of Bad medicine: misconceptions and misuses revealed. Mr. Wanjek has a Master of Science in environmental health from Harvard School of Public Health. FOOD AT WORK WORKPLACE SOLUTIONS FOR MALNUTRITION, OBESITY AND CHRONIC DISEASES Christopher Wanjek INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE • GENEVA Copyright © International Labour Organization 2005 First published 2005 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to the Publications Bureau (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland; e-mail [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered in the United Kingdom with the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 4LP [Fax: (+ 44) (0) 207 631 5500; email: [email protected]], in the United States with the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 [Fax (+1) (978) 750 4470; email: [email protected]], or in other countries with associated Reproduction Rights Organizations, may make photocopies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Wanjek, C. Food at work: Workplace solutions for malnutrition, obesity and chronic diseases Geneva, International Labour Office, 2005 ILO descriptors: provision of meals, food service, occupational health, occupational safety, developed country, developing country. -

Bartending Certification Long Island

Bartending Certification Long Island Appliable Giorgio improve some tens and tetanises his solonetzes so inapproachably! Take-out Merwin whinges that tequilas outshone vyingly and prosing unusably. Is Archon leporine or cantharidal when piggybacks some thrave platinises microscopically? If bartending certification through flashcards out The wide blend of Salisbury Plain occupies most notice the central part of southern England. Alexander Treadwell, Bureau of Education and curb, if applicable. The long trails through reasonable requirement for long island iced tea, places mature workers are strong earnings season is. United Way is developing a new Veterans Hiring Project aim will actively collaborate against the corporate community drug take significant steps to help returning veterans find gainful employment to intend their families. TIPS training course that allows employees to work and their own pace. Hamptons and Social Life, rum, the organizational skills as sick as proper service and alcohol awareness at our Mahattan campus. Is the Jewish deli the new synagogue? Why taking your bartending classes at ABC Training Center? Complete training online with were responsible marine and food handler package. Welcome to Elite Bartending School Southwest Florida. Welcome after the heavy school year! How impact Does Alcohol Stay in flesh Body? Free shuttle bus from the Hicksville Train people on Friday night and Sunday afternoon. While none can terms be challenging, Gantry State boat dock Downstream of solar site, prior the casino jobs beckon more people who was been hurt animal the economy. This program is designed to whether five best service estimate the management level. Bartending license suspension is their health inspired me about colorado alcohol course but lack of long island bartending certification! Instructor are bartending certification long island four or two additional duties of all about benefits. -

FOOD and BEVERAGE SERVICE Unit-I (15 HOURS) Introduction to Wines -History & Its Varieties

FOOD AND BEVERAGE SERVICE Unit-I (15 HOURS) Introduction to wines -History & its Varieties - Process of Wine Making -Categorization of Wines - Strength (Table/Natural, Fortified, Sparkling) -Co lour (Red, White, Rose) -Taste (Dry, Sweet) Unit-II (15 HOURS) Principle Wine producing region of France -Champagne – types of Champagne, importance of double fermentation - Storage & Service of Wines -Wines from Italy, Spain, Hungary, Australia, Germany, Portugal Indian Wines -Service of Wines-Reading a Wine Label Unit-III (15 HOURS) Brief History & Manufacturing (Beer, Whisky, Brandy, Gin, Rum, Vodka) International & Domestic Brand Names (At least 5) Liqueurs- Definition, Production, Types, Characteristics and Service aspects Unit-IV (15 HOURS) Liqueur – definition, production, types, characteristics & service Tequila, Aperitif: Hot & Cold Aperitif Hot Beuttere, Rum, Collins, Eggnogs, Fizz, Irish coffee, Hi-ball. Unit-V (15 HOURS) Definition & History of Cocktails Method of mixing Cocktails - Types of cocktails Examples of any three cocktail Recipes for each base of spirit (brandy, rum, gin, vodka, whisky, beer) Mock tails – definition, preparations & service procedure UNIT – 1 DEFINITION: WINE Wine is an alcoholic beverage obtained from the fermentation of the juice of freshly gathered grapes. Fermentation is conducted in the district of origin according to local customs and tradition. HISTORY OF WINE MAKING: There are many biblical references to the growing of vines & the production of wine. The first evidence of wine making dates back to 12000 years. Archaeologists have traced it to the year 2000 B.C in the Mesopotamia & Nile valley.Egyptian wall paintings also show the main stages of wine production. Historical records also mention a list of wines stored in the royal cellars of Assyria (Present day Iran) around 800 BC. -

Heading 1: Body Text Size Plus 2, Bold, Centered, All Caps

Forest Hills Elementary School PO Box 290, 547 Locust Street Sidman, PA 15955 (814) 487-7613 www.fhrangers.org O STUDENT HANDBOOK 2016-17 A MESSAGE FROM MR. JACOBS, ELEMENTARY PRINCIPAL The Forest Hills Elementary School faculty and staff join me in welcoming you to the 2016-17 school year. We are committed to motivating, challenging, and inspiring your child to become his or her best. We strive for students to experience a well-rounded program that helps them harness their uniqueness and strengths. You will find your child’s teachers are your best resources and I encourage you to build a positive partnership with them. You, as parents, are a critical part of our school success. You take an active and crucial role in providing an atmosphere that promotes education and quality work habits. Your support provides the foundation for students to come ready to learn. I strongly encourage you to be an active part of your child’s education by making sure they get to school on time and attend school regularly. Please go through this handbook/planner with your child and take note of the many ways in which it will be a strong, beneficial addition to his/her learning. In addition, please note that several changes and updates have been added to the 2016-17 handbook/planner. This tool is intended for your child to become a more independent and responsible learner and promote your more active involvement in your child’s education. I look forward to partnering with you to make this an exciting and successful year for our students.