Remarks on the Labyrinth at Side Ivor Winton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal Timothy Hanford Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/427 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by TIMOTHY HANFORD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ©2014 TIMOTHY HANFORD All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ronnie Ancona ________________ _______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Dee L. Clayman ________________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer James Ker Joel Lidov Craig Williams Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by Timothy Hanford Advisor: Professor Ronnie Ancona This dissertation explores the relationship between Senecan tragedy and Virgil’s Aeneid, both on close linguistic as well as larger thematic levels. Senecan tragic characters and choruses often echo the language of Virgil’s epic in provocative ways; these constitute a contrastive reworking of the original Virgilian contents and context, one that has not to date been fully considered by scholars. -

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: the IDEA of the MONUMENT in the ROMAN IMAGINATION of the AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller a Dissertatio

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: THE IDEA OF THE MONUMENT IN THE ROMAN IMAGINATION OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo, Chair Associate Professor Ruth Rothaus Caston Professor Bruce W. Frier Associate Professor Achim Timmermann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people both within and outside of academia. I would first of all like to thank all those on my committee for reading drafts of my work and providing constructive feedback, especially Basil Dufallo and Ruth R. Caston, both of who read my chapters at early stages and pushed me to find what I wanted to say – and say it well. I also cannot thank enough all the graduate students in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan for their support and friendship over the years, without either of which I would have never made it this far. Marin Turk in Slavic Languages and Literature deserves my gratitude, as well, for reading over drafts of my chapters and providing insightful commentary from a non-classicist perspective. And I of course must thank the Department of Classical Studies and Rackham Graduate School for all the financial support that I have received over the years which gave me time and the peace of mind to develop my ideas and write the dissertation that follows. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………………………………iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………....v CHAPTER I. -

Los Ludi En La Roma Arcaica

Martínez-Pinna, Jorge Los ludi en la Roma arcaica De Rebus Antiquis Año 2 Nº 2, 2012 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Martínez-Pinna, Jorge. “Los ludi en la Roma arcaica” [en línea], De Rebus Antiquis, 2 (2012). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/los-ludi-roma-arcaica-pinna.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] (Se recomienda indicar fecha de consulta al final de la cita. Ej: [Fecha de consulta: 19 de agosto de 2010]). DE REBUS ANTIQUIS Año II, Núm. 2 / 2012 ISSN 2250-4923 LOS LUDI EN LA ROMA ARCAICA* DR. JORGE MARTÍNEZ-PINNA Universidad de Málaga Abstract: This paper it is discussed the public games held in Rome during the monarchy. Its creation is due to religious causes, related to fertility (Consualia, ludi Taurei) or to war (Equirria, equus October). The religious and politic fulfillment of the games materializes in the ludi Romani, introduced by King Tarquinius Priscus. It is also considered the so called lusus Troiae, equestrian game exclusive for young people, and likewise with an archaic origin. Key words: Archaic Rome; Games; King. Resumen: En este artículo se analizan los juegos públicos celebrados en Roma durante el período monárquico. Su creación obedece a motivos religiosos, en relación a la fecundidad (Consualia, ludi Taurei) o a la guerra (Equirria, equus October). -

The Idea of the Labyrinth

·THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH · THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages Penelope Reed Doob CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1990 by Cornell University First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 1992 Second paperback printing 2019 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-8014-2393-2 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3845-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3846-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-3847-0 (epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress An open access (OA) ebook edition of this title is available under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by- nc-nd/4.0/. For more information about Cornell University Press’s OA program or to download our OA titles, visit cornellopen.org. Jacket illustration: Photograph courtesy of the Soprintendenza Archeologica, Milan. For GrahamEric Parker worthy companion in multiplicitous mazes and in memory of JudsonBoyce Allen and Constantin Patsalas Contents List of Plates lX Acknowledgments: Four Labyrinths xi Abbreviations XVll Introduction: Charting the Maze 1 The Cretan Labyrinth Myth 11 PART ONE THE LABYRINTH IN THE CLASSICAL AND EARLY CHRISTIAN PERIODS 1. -

Augustus Program and Abstracts

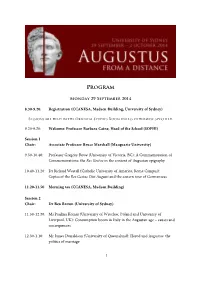

Program Monday 29 September 2014 8.30-9.20: Registration (CCANESA, Madsen Building, University of Sydney) Sessions are held in the Oriental Studies Room unless otherwise specified. 9.20-9.50: Welcome: Professor Barbara Caine, Head of the School (SOPHI) Session 1 Chair: Associate Professor Bruce Marshall (Macquarie University) 9.50-10.40: Professor Gregory Rowe (University of Victoria, BC): A Commemoration of Commemorations: the Res Gestae in the context of Augustan epigraphy 10.40-11.20: Dr Richard Westall (Catholic University of America, Rome Campus): Copies of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti and the eastern tour of Germanicus 11.20-11.50 Morning tea (CCANESA, Madsen Building) Session 2 Chair: Dr Ben Brown (University of Sydney) 11.50-12.30: Ms Paulina Komar (University of Wrocław, Poland and University of Liverpool, UK): Consumption boom in Italy in the Augustan age – causes and consequences 12.30-1.10: Mr James Donaldson (University of Queensland): Herod and Augustus: the politics of marriage 1 1.10-2.30: Lunch (CCANESA, Madsen Building) Session 3 Chair: Dr Lea Beness (Macquarie University) 2.30-3.10: Dr Hannah Mitchell (University of Warwick): Monumentalising aristocratic achievement in triumviral Rome: Octavian’s competition with his peers 3.10-3.50: Dr Frederik Vervaet (University of Melbourne): Subsidia dominationi: the early careers of Tiberius and Drusus revisited 3.50-4.30: Mr Martin Stone (University of Sydney): Marcus Agrippa: Republican statesman or dynastic fodder? 4.30-5.00: Afternoon tea (CCANESA, Madsen Building) Session -

Imperial Messaging in the Redefinition of the Roman Landscape Camille Victoria Delgado Vassar College, [email protected]

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Re-creation and commemoration: Imperial messaging in the redefinition of the Roman landscape Camille Victoria Delgado Vassar College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Delgado, Camille Victoria, "Re-creation and commemoration: Imperial messaging in the redefinition of the Roman landscape" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 573. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! RE$CREATION!AND!COMMEMORATION! Imperial!Messaging!in!the!Redefinition!of!the!Roman! Landscape! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Camille!Victoria!Liboro!Delgado! Greek!and!Roman!Studies!Senior!Thesis! Fall!Semester!2015! Vassar!College TABLE!OF!CONTENTS! ! ! ! ! INTRODUCTION) 1) ! ! ! ! CHAPTER)1:)Imperator) 10) I. Overview! 10! II. Temples! 15! III. Administrative!Buildings! 18! IV. Public!Entertainment!Works! 20! V. Victory!Monuments! 23! VI. Public!Infrastructure!Works! 27! VII. Augustus’!Mausoleum! 29! VIII. Conclusion! 33! Appendix) 36! ! ! ! ! CHAPTER)2:)Il)Duce) 38) I. Overview! 38! II. Redesigning!Roma! 41! III. Foro!Mussolini! 50! IV. Esposizione!Universale!Roma! 56! V. Conclusion! 60! Appendix) 63! ! ! ! ! ! ! CONCLUSION) 70) ) ) ) ) BIBLIOGRAPHY) -

Mr Donn: Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome Mr. Donn and Maxie’s Always Something You Can Use Series Lin & Don Donn, Writers Bill Williams, Editor Dr. Aaron Willis, Project Coordinator Amanda Harter, Editorial Assistant 10200 Jefferson Blvd., P.O. Box 802 Culver City, CA 90232 www.goodyearbooks.com [email protected] (800) 421-4246 ©2011 Good Year Books 10200 Jefferson Blvd., P.O. Box 802 Culver City, CA 90232 United States of America (310) 839-2436 (800) 421-4246 Fax: (800) 944-5432 Fax: (310) 839-2249 www. goodyearbooks.com [email protected] Permission is granted to reproduce individual worksheets for classroom use only. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-59647-410-9 Product Code: GDY837 Table of Contents Preface ...................................................................v Introduction. 1 Setting up the Room .........................................................3 Sections: 1. Welcome To Ancient Rome! ............................................5 • Jupiter ..........................................................8 • Map of Ancient Rome ..............................................10 • Join the Republic! Become a Roman Citizen ...........................................11 2. Early Rome ........................................................13 • Romulus and Remus ...............................................15 • Early Rome ......................................................18 3. Roman Gods and Goddesses ..........................................21 • Mercury ........................................................24 • -

Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 102 (1994) 226–236

FARLAND H. STANLEY JR. CIL II 115: OBSERVATIONS ON THE ONLY SEVIR IUNIOR IN ROMAN SPAIN aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 102 (1994) 226–236 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 226 CIL II 115: OBSERVATIONS ON THE ONLY SEVIR IUNIOR IN ROMAN SPAIN Spurious inscriptions are an interesting aspect of epigraphical studies, as has been testified by those who have considered the falsae et alienae sections of the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum.1 Commenting on the list of fraudulent inscriptions in the CIL, Arthur E.Gordon emphasized that part of the interest in these false inscriptions lies in the possibility that "... at any time someone may challenge the list, by arguing either for the deletion of an item from the list or for the addition of an item ..."2 One inscription which may fit into this category is CIL II 115 ( = ILER 5673). It is particularly intriguing because, despite its long-term listing as a false inscription, recent books have included it in their texts without making reference to its spurious status.3 Because some appear to have accepted the inscription, without discussing why, an inquiry may be in order to consider possible reasons why its history as an invalid inscription could apparently be disregarded. Long regarded as false, the inscription purports to record the career of a Roman soldier named C. Antonius Flavinus of the legion II Augusta from Ebora Liberalitas (modern Évora in Portugal). Certainly, one of the persuasive reasons why CIL II 115 has been considered to be fraudulent is because it was first catalogued by the infamous sixteen century forger André de Resende (1498-1573), bishop of Évora in Portugal.4 And, as Abbott pointed out 1 On general discussion about spurious inscriptions see: Frank Frost Abbott, "Some Spurious Inscriptions and Their Authors Classical Philology 3 (1908) 22-30; John E.Sandys, Latin Epigraphy I: An Introduction to the Study of Latin Inscriptions (Chicago 1974: reprint of 1927 edition) 204-206; James C.Egbert, Introduction to the Study of Latin Inscriptions (New York 1923) 10-12. -

Virgil Society Book 2.Qxd.Qxd

Proceedings o f the Virgil Society 25 (2004) 63-72 Copyright 2004 The Name of the Game: The Troia, and History and Spectacle in Aeneid 5 A paper given to the Virgil Society on 23 February 2002 hen Heinze dismisses the games in Aeneid 5 as a weakly motivated imitation of the games in Iliad 23, he does so mainly because Aeneas' games are commemorative, an Wanniversary celebration, rather than the immediate representation of grief offered by the Homeric funeral games. For Heinze, Virgil's decision to place the games after the Carthaginian episode meant the ‘not very welcome consequence [. ], that it needed to be a memorial celebration, and not as in the Iliad a real funeral before the freshly dug grave'. The lack of a fresh grave means that the Virgilian event ‘is not something unique, but something which can be repeated at will'.1 And that, I suspect, is precisely the point for the Roman poet, who is deliberately drawing attention to the poem's ‘belatedness'. In a culture that is obsessed with anniversaries and annual rites, with the measurement and organisation of time itself, and with the organisation and presentation of spectacular ritual, a freshly dug grave is not in itself particularly important or necessary.2 So, the Virgilian games should be understood to improve on the Homeric precedent by inserting the death of Anchises into a kind of prototype ritual calendar, invented by Aeneas on his return to Sicily on the anniversary of his father's death.3 The ‘improvement’ is not only a matter of poetic rivalry, but more importantly perhaps serves to remind the reader of the fact that archaic Greece, unlike Augustan Rome, did not conceive of time as a continuous, linked sequence of years. -

From the Gracchi to Nero: a History of Rome 133 BC to AD 68

From the Gracchi to Nero ‘Still the best introduction to Roman history’ Miriam Griffin, University of Oxford, UK ‘For a concise, factual narrative of the Roman world’s trau- matic transformation from Republic to Empire, [it] remains unsurpassed. As a foundation for university and college courses, it is invaluable.’ Richard Talbert, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, USA ‘Without a rival as a guide to the intricacies of Republican politics.’ Greg Woolf, University of St. Andrews, UK ‘A classic textbook: clear, authoritative and balanced in its judgements . it has established itself as the fundamental modern work of reference for teachers, sixth-formers and university students . it is still the best and most reliable modern account of the period.’ Tim Cornell, University of Manchester, UK ‘This book is a modern classic. It provides a clear narrative of the two centuries from 133 B.C. to 68 A.D., but it is espe- cially valuable for Scullard’s extensive footnotes which pro- vide undergraduates with both the ancient sources and the most important scholarly contributions.’ Ronald Mellor, University of California at Los Angeles, USA H. H. Scullard From the Gracchi to Nero A history of Rome from 133 b.c. to a.d. 68 With a new foreword by Dominic Rathbone London and New York First published 1959 by Methuen & Co. First published in Routledge Classics 2011 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2010. -

STUDIES in AENEAS' REACTIONS to PROPHECIES by ASHLEE

THE PROPHETIC LEGACY: STUDIES IN AENEAS’ REACTIONS TO PROPHECIES by ASHLEE WARREN (Under the Direction of Sarah Spence) ABSTRACT Throughout the Aeneid , Vergil’s hero is exposed to both short-term prophecies, which foreshadow events in the future of the poem, and long-term prophecies, which call attention to the future of Rome. Between the first and second halves of the poem, there is a subtle shift in both the types of prophecies delivered and in the hero’s reactions to the prophecies that he receives. This contrast seems to suggest that Aeneas is disturbed by prophecies when they concern his own future and confused by prophecies when they concern Ascanius, for whom the future of Rome is intended. Through the skillful incorporation of his audience into the poem’s long-term prophecies, Vergil makes this contrast that much more effective, carefully conveying his own hopes and fears about the future under Augustus. INDEX WORDS: Aeneas, Aeneid , Ascanius, Augustus, Prophecy, Vergil THE PROPHETIC LEGACY: STUDIES IN AENEAS’ REACTIONS TO PROPHECIES by ASHLEE WARREN B. A., University of Tennessee, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2008 © 2008 Ashlee Warren All Rights Reserved THE PROPHETIC LEGACY: STUDIES IN AENEAS’ REACTIONS TO PROPHECIES by ASHLEE WARREN Major Professor: Sarah Spence Committee: T. Keith Dix Christine Perkell Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2008 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my sincerest gratitude to Dr. -

Death Ante Ora Parentum in Virgil's Aeneid

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Classical Studies Faculty Research Classical Studies Department Fall 2009 Death Ante Ora Parentum in Virgil’s Aeneid Timothy M. O'Sullivan Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/class_faculty Part of the Classics Commons Repository Citation O'Sullivan, T.M. (2009). Death ante ora parentum in Virgil's Aeneid. Transactions of the American Philological Association, 139(2), 447-486. doi:10.1353/apa.0.0027 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transactions of the American Philological Association 139 (2009) 447–486 Death ante ora parentum in Virgil’s Aeneid* timothy m. o’sullivan Trinity University matres atque viri defunctaque corpora vita magnanimum heroum, pueri innuptaeque puellae, impositique rogis iuvenes ante ora parentum Virg. Geo. 4.475–77 = Aen. 6.306–8 summary: Virgil’s Aeneid includes a number of scenes in which children die in front of their parents. While the motif has a Homeric precedent, Virgil’s inven- tion of a formula (ante ora parentum: “before the faces of one’s parents”) sug- gests a particular interest in the theme. An analysis of scenes where the formula recurs (such as Aeneas’s shipwreck, the fall of Troy, and the lusus Troiae) reveals a metapoetic resonance behind the motif, with the parent-child relationship acting as a metaphor for authorial influence and artistic creation.