Death Ante Ora Parentum in Virgil's Aeneid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal Timothy Hanford Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/427 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by TIMOTHY HANFORD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ©2014 TIMOTHY HANFORD All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ronnie Ancona ________________ _______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Dee L. Clayman ________________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer James Ker Joel Lidov Craig Williams Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by Timothy Hanford Advisor: Professor Ronnie Ancona This dissertation explores the relationship between Senecan tragedy and Virgil’s Aeneid, both on close linguistic as well as larger thematic levels. Senecan tragic characters and choruses often echo the language of Virgil’s epic in provocative ways; these constitute a contrastive reworking of the original Virgilian contents and context, one that has not to date been fully considered by scholars. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: the IDEA of the MONUMENT in the ROMAN IMAGINATION of the AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller a Dissertatio

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: THE IDEA OF THE MONUMENT IN THE ROMAN IMAGINATION OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo, Chair Associate Professor Ruth Rothaus Caston Professor Bruce W. Frier Associate Professor Achim Timmermann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people both within and outside of academia. I would first of all like to thank all those on my committee for reading drafts of my work and providing constructive feedback, especially Basil Dufallo and Ruth R. Caston, both of who read my chapters at early stages and pushed me to find what I wanted to say – and say it well. I also cannot thank enough all the graduate students in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan for their support and friendship over the years, without either of which I would have never made it this far. Marin Turk in Slavic Languages and Literature deserves my gratitude, as well, for reading over drafts of my chapters and providing insightful commentary from a non-classicist perspective. And I of course must thank the Department of Classical Studies and Rackham Graduate School for all the financial support that I have received over the years which gave me time and the peace of mind to develop my ideas and write the dissertation that follows. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………………………………iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………....v CHAPTER I. -

Los Ludi En La Roma Arcaica

Martínez-Pinna, Jorge Los ludi en la Roma arcaica De Rebus Antiquis Año 2 Nº 2, 2012 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Martínez-Pinna, Jorge. “Los ludi en la Roma arcaica” [en línea], De Rebus Antiquis, 2 (2012). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/los-ludi-roma-arcaica-pinna.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] (Se recomienda indicar fecha de consulta al final de la cita. Ej: [Fecha de consulta: 19 de agosto de 2010]). DE REBUS ANTIQUIS Año II, Núm. 2 / 2012 ISSN 2250-4923 LOS LUDI EN LA ROMA ARCAICA* DR. JORGE MARTÍNEZ-PINNA Universidad de Málaga Abstract: This paper it is discussed the public games held in Rome during the monarchy. Its creation is due to religious causes, related to fertility (Consualia, ludi Taurei) or to war (Equirria, equus October). The religious and politic fulfillment of the games materializes in the ludi Romani, introduced by King Tarquinius Priscus. It is also considered the so called lusus Troiae, equestrian game exclusive for young people, and likewise with an archaic origin. Key words: Archaic Rome; Games; King. Resumen: En este artículo se analizan los juegos públicos celebrados en Roma durante el período monárquico. Su creación obedece a motivos religiosos, en relación a la fecundidad (Consualia, ludi Taurei) o a la guerra (Equirria, equus October). -

Metempsychosis in Aeneid Six Author(S): E

Metempsychosis in Aeneid Six Author(s): E. L. Harrison Reviewed work(s): Source: The Classical Journal, Vol. 73, No. 3 (Feb. - Mar., 1978), pp. 193-197 Published by: The Classical Association of the Middle West and South Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3296685 . Accessed: 12/02/2013 21:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Classical Association of the Middle West and South is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Classical Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Tue, 12 Feb 2013 21:07:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions METEMPSYCHOSISIN AENEID SIX The purposeof this note is to suggest that, in orderto understandmore clearly the lines in which Virgil preparesthe way for his paradeof heroes in Book Six (679-755), we need to appreciatethe difficulties presentedby the introduction of such an episode, and consider how he handled them.' Although we can only surmise, it seems highly probablethat, influencedby the practice at the funerals of prominentRomans of having relatives walk in processionwearing portrait-masks of the dead man's ancestors,2Virgil decided to stage a similar spectacle on a granderscale, including in its scope the great figures of Rome's past. -

The Idea of the Labyrinth

·THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH · THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages Penelope Reed Doob CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1990 by Cornell University First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 1992 Second paperback printing 2019 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-8014-2393-2 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3845-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3846-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-3847-0 (epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress An open access (OA) ebook edition of this title is available under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by- nc-nd/4.0/. For more information about Cornell University Press’s OA program or to download our OA titles, visit cornellopen.org. Jacket illustration: Photograph courtesy of the Soprintendenza Archeologica, Milan. For GrahamEric Parker worthy companion in multiplicitous mazes and in memory of JudsonBoyce Allen and Constantin Patsalas Contents List of Plates lX Acknowledgments: Four Labyrinths xi Abbreviations XVll Introduction: Charting the Maze 1 The Cretan Labyrinth Myth 11 PART ONE THE LABYRINTH IN THE CLASSICAL AND EARLY CHRISTIAN PERIODS 1. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Aristocratic Identities in the Roman Senate from the Social War to the Flavian Dynasty

Aristocratic Identities in the Roman Senate From the Social War to the Flavian Dynasty By Jessica J. Stephens A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Greek and Roman History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Potter, chair Professor Bruce W. Frier Professor Richard Janko Professor Nicola Terrenato [Type text] [Type text] © Jessica J. Stephens 2016 Dedication To those of us who do not hesitate to take the long and winding road, who are stars in someone else’s sky, and who walk the hillside in the sweet summer sun. ii [Type text] [Type text] Acknowledgements I owe my deep gratitude to many people whose intellectual, emotional, and financial support made my journey possible. Without Dr. T., Eric, Jay, and Maryanne, my academic career would have never begun and I will forever be grateful for the opportunities they gave me. At Michigan, guidance in negotiating the administrative side of the PhD given by Kathleen and Michelle has been invaluable, and I have treasured the conversations I have had with them and Terre, Diana, and Molly about gardening and travelling. The network of gardeners at Project Grow has provided me with hundreds of hours of joy and a respite from the stress of the academy. I owe many thanks to my fellow graduate students, not only for attending the brown bags and Three Field Talks I gave that helped shape this project, but also for their astute feedback, wonderful camaraderie, and constant support over our many years together. Due particular recognition for reading chapters, lengthy discussions, office friendships, and hours of good company are the following: Michael McOsker, Karen Acton, Beth Platte, Trevor Kilgore, Patrick Parker, Anna Whittington, Gene Cassedy, Ryan Hughes, Ananda Burra, Tim Hart, Matt Naglak, Garrett Ryan, and Ellen Cole Lee. -

Julius Caesar

Working Paper CEsA CSG 168/2018 ANCIENT ROMAN POLITICS – JULIUS CAESAR Maria SOUSA GALITO Abstract Julius Caesar (JC) survived two civil wars: first, leaded by Cornelius Sulla and Gaius Marius; and second by himself and Pompeius Magnus. Until he was stabbed to death, at a senate session, in the Ides of March of 44 BC. JC has always been loved or hated, since he was alive and throughout History. He was a war hero, as many others. He was a patrician, among many. He was a roman Dictator, but not the only one. So what did he do exactly to get all this attention? Why did he stand out so much from the crowd? What did he represent? JC was a front-runner of his time, not a modern leader of the XXI century; and there are things not accepted today that were considered courageous or even extraordinary achievements back then. This text tries to explain why it’s important to focus on the man; on his life achievements before becoming the most powerful man in Rome; and why he stood out from every other man. Keywords Caesar, Politics, Military, Religion, Assassination. Sumário Júlio César (JC) sobreviveu a duas guerras civis: primeiro, lideradas por Cornélio Sula e Caio Mário; e depois por ele e Pompeius Magnus. Até ser esfaqueado numa sessão do senado nos Idos de Março de 44 AC. JC foi sempre amado ou odiado, quando ainda era vivo e ao longo da História. Ele foi um herói de guerra, como outros. Ele era um patrício, entre muitos. Ele foi um ditador romano, mas não o único. -

Augustus Program and Abstracts

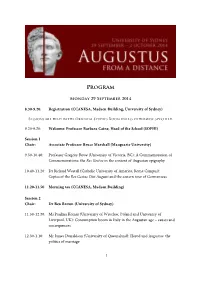

Program Monday 29 September 2014 8.30-9.20: Registration (CCANESA, Madsen Building, University of Sydney) Sessions are held in the Oriental Studies Room unless otherwise specified. 9.20-9.50: Welcome: Professor Barbara Caine, Head of the School (SOPHI) Session 1 Chair: Associate Professor Bruce Marshall (Macquarie University) 9.50-10.40: Professor Gregory Rowe (University of Victoria, BC): A Commemoration of Commemorations: the Res Gestae in the context of Augustan epigraphy 10.40-11.20: Dr Richard Westall (Catholic University of America, Rome Campus): Copies of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti and the eastern tour of Germanicus 11.20-11.50 Morning tea (CCANESA, Madsen Building) Session 2 Chair: Dr Ben Brown (University of Sydney) 11.50-12.30: Ms Paulina Komar (University of Wrocław, Poland and University of Liverpool, UK): Consumption boom in Italy in the Augustan age – causes and consequences 12.30-1.10: Mr James Donaldson (University of Queensland): Herod and Augustus: the politics of marriage 1 1.10-2.30: Lunch (CCANESA, Madsen Building) Session 3 Chair: Dr Lea Beness (Macquarie University) 2.30-3.10: Dr Hannah Mitchell (University of Warwick): Monumentalising aristocratic achievement in triumviral Rome: Octavian’s competition with his peers 3.10-3.50: Dr Frederik Vervaet (University of Melbourne): Subsidia dominationi: the early careers of Tiberius and Drusus revisited 3.50-4.30: Mr Martin Stone (University of Sydney): Marcus Agrippa: Republican statesman or dynastic fodder? 4.30-5.00: Afternoon tea (CCANESA, Madsen Building) Session -

Ap Latin Summer Assignment

AP LATIN SUMMER ASSIGNMENT: Cardinal Gibbons High School Magistra Crabbe: 2018/2019 Assignment: Read and prepare for a test on Books I, II, IV, VI, VIII, and XII of Virgil’s Aeneid. Directions: ● Carefully read the introduction to the Aeneid written by Bernard Knox, and fill out the corresponding reflection questions. These questions will be collected and graded in August. Content from the introduction will be represented on the test in August. ● Carefully read the English Portions of the Syllabus from Virgil’s Aeneid. This is the entirety of Books I, II, IV, VI, VIII, and XII of Virgil’s Aeneid. Students should read the Revised Penguin Edition by David West. Hard copies of this book are available from Mrs. Crabbe in room 211. ● Fill out the corresponding study questions for each book. In August, these study questions will be collected and graded. ● Students will take a test on these readings before beginning the Latin portion of the AP Syllabus. Index of This Document: Introduction to the Aeneid by Bernard Knox: pp 126 Reading Questions for Introduction: pp 2734 Book I Reading Questions: pp 3543 Book II Reading Questions: pp 4449 Book IV Reading Questions: pp 5056 Book VI Reading Questions: pp 5764 Book VIII Reading Questions: pp 6568 Book XII Reading Questions: pp 6974 Suggested Reading Schedule: May 28th June 1st: Relax this week and recover from your finals. Drink lots of water. Get plenty of sleep. Spend time outside and do something fun with your friends. Help your parents around the house. -

Troy Myth and Reality

Part 1 Large print exhibition text Troy myth and reality Please do not remove from the exhibition This two-part guide provides all the exhibition text in large print. There are further resources available for blind and partially sighted people: Audio described tours for blind and partially sighted visitors, led by the exhibition curator and a trained audio describer will explore highlight objects from the exhibition. Tours are accompanied by a handling session. Booking is essential (£7.50 members and access companions go free) please contact: Email: [email protected] Telephone: 020 7323 8971 Thursday 12 December 2019 14.00–17.00 and Saturday 11 January 2020 14.00–17.00 1 There is also an object handling desk at the exhibition entrance that is open daily from 11.00 to 16.00. For any queries about access at the British Museum please email [email protected] 2 Sponsor’sThe Trojan statement War For more than a century BP has been providing energy to advance human progress. Today we are delighted to help you learn more about the city of Troy through extraordinary artefacts and works of art, inspired by the stories of the Trojan War. Explore the myth, archaeology and legacy of this legendary city. BP believes that access to arts and culture helps to build a more inspired and creative society. That’s why, through 23 years of partnership with the British Museum, we’ve helped nearly five million people gain a deeper understanding of world cultures with BP exhibitions, displays and performances. Our support for the arts forms part of our wider contribution to UK society and we hope you enjoy this exhibition.