The Urban Plebs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-17549-4 - The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome J. Bert Lott Table of Contents More information CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables page ix Abbreviations xi Acknowledgments xiii 1 Introducing Neighborhoods at Rome and Elsewhere 1 Neighborhoods at Rome 4 Defining Neighborhoods 12 Defining Vici in Ancient Rome 13 Neighborhoods in Modern Thought 18 Voluntary Associations 24 Conclusion 25 2 Neighborhoods in the Roman Republic 28 Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Neighborhood Religion 30 The Middle Republic 37 The Late Republic 45 Social Disaffection, Populares, and Community Action 45 Magistri Vici and Collegia Compitalicia 51 Neighborhoods in the Final Years of the Republic 55 Conclusion 59 3 Republic to Empire 61 Julius Caesar 61 The Triumvirate 65 The Augustan Principate Before 7 b.c.e. 67 A Statue for Mercurius on the Esquiline 73 vii © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-17549-4 - The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome J. Bert Lott Table of Contents More information CONTENTS 4 The Reforms of Augustus 81 The Mechanics of Reform 84 The Ideology of Reform 98 Neighborhood Religion 106 Emperor and Neighborhood 117 Conclusion 126 5 The Artifacts of Neighborhood Culture 128 Think Globally, Act Locally 130 Altars in the Neighborhoods 136 Altar from the Vicus Statae Matris 137 Vatican Inventory 311 14 0 Altar of the Vicus Aesculeti 142 Altar of the Vicus Sandaliarius 144 Ara Augusta of Lucretius Zethus 146 Two Augustan Neighborhoods 148 Vicus Compiti Acili 148 Vicus of the Fasti Magistrorum Vici 152 Numerius Lucius Hermeros 161 Some Other Dedications and Magistri 165 Conclusion 168 6 Conclusion 172 Conclusion 175 Appendix. -

Women's Costume and Feminine Civic Morality in Augustan Rome

Gender & History ISSN 0953–5233 Judith Lynn Sebesta, ‘Women’s Costume and Feminine Civic Morality in Augustan Rome’ Gender & History, Vol.9 No.3 November 1997, pp. 529–541. Women’s Costume and Feminine Civic Morality in Augustan Rome JUDITH LYNN SEBESTA Augustus was eager to revive the traditional dress of the Romans. One day in the Forum he saw a group of citizens dressed in dark garments and exclaimed indignantly, ‘Behold the masters of the world, the toga-clad race!’ He thereupon instructed the aediles that no Roman citizen was to enter the Forum, or even be in its vicinity, unless he were properly clad in a toga.1 In the terms of Augustan ideology, the avoidance of Roman dress by Romans was another sign of their abandoning the traditional Roman way of life, character and values in preference for the high culture, pomp, and moral and philosophical relativism of the Hellenistic East. This accultura- tion of foreign ways was frequently claimed to have brought Republican Rome to the edge of destruction in both the public and private spheres.2 Roman authors of the late first century BCE depict women in particular as devoted to their own selfish pleasure, marrying and divorcing at will, and preferring childlessness and abortion to raising a family. Such women were regarded as having abandoned their traditional role of custos domi (‘pre- server of the house/hold’), a role that correlated a wife’s body and her husband’s household. A Roman wife was expected to maintain her body’s inviolability and to preserve her husband’s possessions, while increasing his family by bearing children and enriching his wealth through her labors.3 The mindful care of the ideal wife was epitomized in the legendary story of the chaste Lucretia, who became an important symbol of wifehood in Augustan literature. -

Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal Timothy Hanford Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/427 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by TIMOTHY HANFORD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ©2014 TIMOTHY HANFORD All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ronnie Ancona ________________ _______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Dee L. Clayman ________________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer James Ker Joel Lidov Craig Williams Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by Timothy Hanford Advisor: Professor Ronnie Ancona This dissertation explores the relationship between Senecan tragedy and Virgil’s Aeneid, both on close linguistic as well as larger thematic levels. Senecan tragic characters and choruses often echo the language of Virgil’s epic in provocative ways; these constitute a contrastive reworking of the original Virgilian contents and context, one that has not to date been fully considered by scholars. -

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: the IDEA of the MONUMENT in the ROMAN IMAGINATION of the AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller a Dissertatio

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: THE IDEA OF THE MONUMENT IN THE ROMAN IMAGINATION OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo, Chair Associate Professor Ruth Rothaus Caston Professor Bruce W. Frier Associate Professor Achim Timmermann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people both within and outside of academia. I would first of all like to thank all those on my committee for reading drafts of my work and providing constructive feedback, especially Basil Dufallo and Ruth R. Caston, both of who read my chapters at early stages and pushed me to find what I wanted to say – and say it well. I also cannot thank enough all the graduate students in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan for their support and friendship over the years, without either of which I would have never made it this far. Marin Turk in Slavic Languages and Literature deserves my gratitude, as well, for reading over drafts of my chapters and providing insightful commentary from a non-classicist perspective. And I of course must thank the Department of Classical Studies and Rackham Graduate School for all the financial support that I have received over the years which gave me time and the peace of mind to develop my ideas and write the dissertation that follows. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………………………………iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………....v CHAPTER I. -

Los Ludi En La Roma Arcaica

Martínez-Pinna, Jorge Los ludi en la Roma arcaica De Rebus Antiquis Año 2 Nº 2, 2012 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Martínez-Pinna, Jorge. “Los ludi en la Roma arcaica” [en línea], De Rebus Antiquis, 2 (2012). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/los-ludi-roma-arcaica-pinna.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] (Se recomienda indicar fecha de consulta al final de la cita. Ej: [Fecha de consulta: 19 de agosto de 2010]). DE REBUS ANTIQUIS Año II, Núm. 2 / 2012 ISSN 2250-4923 LOS LUDI EN LA ROMA ARCAICA* DR. JORGE MARTÍNEZ-PINNA Universidad de Málaga Abstract: This paper it is discussed the public games held in Rome during the monarchy. Its creation is due to religious causes, related to fertility (Consualia, ludi Taurei) or to war (Equirria, equus October). The religious and politic fulfillment of the games materializes in the ludi Romani, introduced by King Tarquinius Priscus. It is also considered the so called lusus Troiae, equestrian game exclusive for young people, and likewise with an archaic origin. Key words: Archaic Rome; Games; King. Resumen: En este artículo se analizan los juegos públicos celebrados en Roma durante el período monárquico. Su creación obedece a motivos religiosos, en relación a la fecundidad (Consualia, ludi Taurei) o a la guerra (Equirria, equus October). -

The Shops and Shopkeepers of Ancient Rome

CHARM 2015 Proceedings Marketing an Urban Identity: The Shops and Shopkeepers of Ancient Rome 135 Rhodora G. Vennarucci Lecturer of Classics, Department of World Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, University of Arkansas, U.S.A. Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to explore the development of fixed-point retailing in the city of ancient Rome between the 2nd c BCE and the 2nd/3rd c CE. Changes in the socio-economic environment during the 2nd c BCE caused the structure of Rome’s urban retail system to shift from one chiefly reliant on temporary markets and fairs to one typified by permanent shops. As shops came to dominate the architectural experience of Rome’s streetscapes, shopkeepers took advantage of the increased visibility by focusing their marketing strategies on their shop designs. Through this process, the shopkeeper and his shop actively contributed to urban placemaking and the distribution of an urban identity at Rome. Design/methodology/approach – This paper employs an interdisciplinary approach in its analysis, combining textual, archaeological, and art historical materials with comparative history and modern marketing theory. Research limitation/implications – Retailing in ancient Rome remains a neglected area of study on account of the traditional view among economic historians that the retail trades of pre-industrial societies were primitive and unsophisticated. This paper challenges traditional models of marketing history by establishing the shop as both the dominant method of urban distribution and the chief means for advertising at Rome. Keywords – Ancient Rome, Ostia, Shop Design, Advertising, Retail Change, Urban Identity Paper Type – Research Paper Introduction The permanent Roman shop was a locus for both commercial and social exchanges, and the shopkeeper acted as the mediator of these exchanges. -

An Examination of the Fasti Praenestini Julia C

The Roman Calendar as an Expression of Augustan Culture: An Examination of the Fasti Praenestini Julia C. Hernández Around the year 6 AD, the Roman grammarian Marcus Verrius Flaccus erected a calendar in the forum of his hometown of Praeneste. The fragments which remain of his work are unique among extant examples of Roman fasti, or calendars. They are remarkable not only because of their indication that Verrius Flaccus’ Fasti Praenestini was considerably larger in physical size than the average Roman fasti, but also because of the richly detailed entries for various days on the calendar, which are substantially longer and more informative than those found on any extant calendar inscriptions. The frequent mentions of Augutus in the entries of the Fasti Praenestini, in addition to Verrius Flaccus’ personal relationship with Augustus as related by Suetonius (Suet. Gram. 17), have led some scholars, most notably Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, to interpret the creation of the Fasti Praenestini as an act of propaganda supporting the new Augustan regime.1 However, this limited interpretation fails to take into account the implications of this calendar’s unique form and content. A careful examination of the Fasti Praenestini reveals that its unusual character reflects the creative experimentation of Marcus Verrius Flaccus, the individual who created it, and the broad interests of the Roman public, by whom it was to be viewed. The uniquness of the Fasti Praenestini among inscribed calendars is matched by Ovid’s literary expression of the calendar composed in elegiac couplets. This unprecedented literary approach to the calendar has garnered much more attention from scholars over the years than has the Fasti Praenestini. -

The Idea of the Labyrinth

·THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH · THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages Penelope Reed Doob CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1990 by Cornell University First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 1992 Second paperback printing 2019 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-8014-2393-2 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3845-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3846-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-3847-0 (epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress An open access (OA) ebook edition of this title is available under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by- nc-nd/4.0/. For more information about Cornell University Press’s OA program or to download our OA titles, visit cornellopen.org. Jacket illustration: Photograph courtesy of the Soprintendenza Archeologica, Milan. For GrahamEric Parker worthy companion in multiplicitous mazes and in memory of JudsonBoyce Allen and Constantin Patsalas Contents List of Plates lX Acknowledgments: Four Labyrinths xi Abbreviations XVll Introduction: Charting the Maze 1 The Cretan Labyrinth Myth 11 PART ONE THE LABYRINTH IN THE CLASSICAL AND EARLY CHRISTIAN PERIODS 1. -

The Sophistic Roman: Education and Status in Quintilian, Tacitus and Pliny Brandon F. Jones a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

The Sophistic Roman: Education and Status in Quintilian, Tacitus and Pliny Brandon F. Jones A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Alain Gowing, Chair Catherine Connors Alexander Hollmann Deborah Kamen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics ©Copyright 2015 Brandon F. Jones University of Washington Abstract The Sophistic Roman: Education and Status in Quintilian, Tacitus and Pliny Brandon F. Jones Chair of Supervisory Commitee: Professor Alain Gowing Department of Classics This study is about the construction of identity and self-promotion of status by means of elite education during the first and second centuries CE, a cultural and historical period termed by many as the Second Sophistic. Though the Second Sophistic has traditionally been treated as a Greek cultural movement, individual Romans also viewed engagement with a past, Greek or otherwise, as a way of displaying education and authority, and, thereby, of promoting status. Readings of the work of Quintilian, Tacitus and Pliny, first- and second-century Latin prose authors, reveal a remarkable engagement with the methodologies and motivations employed by their Greek contemporaries—Dio of Prusa, Plutarch, Lucian and Philostratus, most particularly. The first two chapters of this study illustrate and explain the centrality of Greek in the Roman educational system. The final three chapters focus on Roman displays of that acquired Greek paideia in language, literature and oratory, respectively. As these chapters demonstrate, the social practices of paideia and their deployment were a multi-cultural phenomenon. Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................... 2 Introduction ....................................................................................... 4 Chapter One. -

A Resolution of the Political Activities of Philo with the Politico-Messianic Ideas Expressed in His Works Leonard Jay Greenspoon

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research Spring 1970 A resolution of the political activities of Philo with the politico-messianic ideas expressed in his works Leonard Jay Greenspoon Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Greenspoon, Leonard Jay, "A resolution of the political activities of Philo with the politico-messianic ideas expressed in his works" (1970). Master's Theses. Paper 308. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A BESOLUTIOO OF 1'HE POLITICAL ACTIVITIES OF mn.,o wrm THE POLITICO-MESSIANIC IDF.AS EXPRESSED IN HIS WVRKS BY LE<llARD JAY GBEF.:N'SPOCFT A THESIS SU'.BMIT'1.'1ID TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF' THE UNIVERSITY OF P.ICHMOND m CAIIDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS JUNE 1970 LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF RV:::-tMONO VIRGINIA APPROVED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF ANCIENT LANGUAGES DfuECTOR ii CONTENTS PREFACE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • iv CHAl?TER I. JEWS AND GENTILFS m JUDEA AND EGYPT • • • • • • • • • l Palestine fran 63 B.c. to 60 A.D •••••• • • • l Egypt from the Beginning or the Hellenistic Age to 38 A.D. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 19 Gaiua, Claudius and the Jews • • • . • • 33 POLITICS, MESSIA!JISM, AND PHILO • • # • • • • . 42 Polltics • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 42 Messianism • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 52 CHAP.fER III. THE RESOLUTION . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 67 APPENDIX I • • • • • • • • • • • . - • • • • • • • • • • 81 APPENDIX II . .. 83 BIBLIOORA.PHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 85 VI'.t'A. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • \ iii LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND -- . -

Die Römisch-Rechtlichen Quellen Der Grammatiker Verrius Flaccus Und Festus Pompeius

Dirksen, Heinrich Eduard Die römisch-rechtlichen Quellen der Grammatiker Verrius Flaccus und Festus Pompeius [S.n.] 1852 eBooks von / from Digitalisiert von / Digitised by Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin V *» * H\ + *+i rv o^° % Ijmi Itffe Die römisch-rechtlichen Quellen der Grammatiker Verrius Flaccus und Festus Pompeius. Von H. E. DIRKSEN. [Gelesen in der Akademie der Wissenschaften am 10. Junius 1852.] JLJS ist zur Genüge bekannt, dafs wir die reichhaltigsten Beiträge zur Kunde des älteren römischen Rechts, und namentlich einen nicht unerheblichen Schatz von Bruchstücken wichtiger Gesetzesurkunden so wie sonstiger juri stischer Schriftstücke der Römer, dem Werke De verborum significa- tione des gelehrten Grammatikers M. Verrius Flaccus zu verdanken haben, eines Zeitgenossen der Kaiser Augustus und Tiberius (1). Von die- serSchrift (2) ist das Fragment eines Auszuges, den der Grammatiker Festus Pompeius, wahrscheinlich im Laufe des vierten Jahrhunderts n. Chr., veranstaltet hat (3), in einer einzigen höchst lückenhaften Handschrift, auf unsere Zeit gekommen. Daneben besitzen wir die vollständige, sehr mangel haft redigirte, Ueberarbeitung derselben Epitome des Festus, welche einen christlichen Geistlichen Namens Pau lus, der vor der Mitte des achten Jahr hunderts lebte und von seinen Zeitgenossen als Glossator bezeichnet wird (4), zum Verfasser hat. (*) Die neueste Untersuchung über das Zeitalter desselben findet man in R. Merkel's Ausg. der Fastorum libb. VI. des Ovidius. Prolegom. p. XCIV. sqq. Beroi. 1841. 8. (2) Ueber die Zeit von deren Abfassung vergl. O. Mü II er's Ausgabe des F es tus. pag.XXIX. Lips 183p. 4. und Lachmann, in der Zeitschr. f. geschichtl. Rs. W. Bd. 11. S. 116. (3) J. C. -

Augustus Program and Abstracts

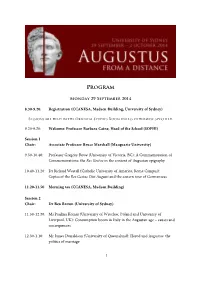

Program Monday 29 September 2014 8.30-9.20: Registration (CCANESA, Madsen Building, University of Sydney) Sessions are held in the Oriental Studies Room unless otherwise specified. 9.20-9.50: Welcome: Professor Barbara Caine, Head of the School (SOPHI) Session 1 Chair: Associate Professor Bruce Marshall (Macquarie University) 9.50-10.40: Professor Gregory Rowe (University of Victoria, BC): A Commemoration of Commemorations: the Res Gestae in the context of Augustan epigraphy 10.40-11.20: Dr Richard Westall (Catholic University of America, Rome Campus): Copies of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti and the eastern tour of Germanicus 11.20-11.50 Morning tea (CCANESA, Madsen Building) Session 2 Chair: Dr Ben Brown (University of Sydney) 11.50-12.30: Ms Paulina Komar (University of Wrocław, Poland and University of Liverpool, UK): Consumption boom in Italy in the Augustan age – causes and consequences 12.30-1.10: Mr James Donaldson (University of Queensland): Herod and Augustus: the politics of marriage 1 1.10-2.30: Lunch (CCANESA, Madsen Building) Session 3 Chair: Dr Lea Beness (Macquarie University) 2.30-3.10: Dr Hannah Mitchell (University of Warwick): Monumentalising aristocratic achievement in triumviral Rome: Octavian’s competition with his peers 3.10-3.50: Dr Frederik Vervaet (University of Melbourne): Subsidia dominationi: the early careers of Tiberius and Drusus revisited 3.50-4.30: Mr Martin Stone (University of Sydney): Marcus Agrippa: Republican statesman or dynastic fodder? 4.30-5.00: Afternoon tea (CCANESA, Madsen Building) Session