Polarized Politics: Fassbinder's Use of 'Spiele(N)' in Die Dritte Generation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

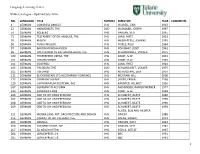

1 Language Learning Center Video Catalogue

Language Learning Center Video Catalogue – Updated July 2016 NO. LANGUAGE TITLE FORMAT DIRECTOR YEAR COMMENTS 4 GERMAN CONGRESS DANCES VHS CHARELL, ERIK 1932 22 GERMAN HARMONISTS, THE DVD VILSMAIER, JOSEPH 1997 54 GERMAN KOLBERG VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1945 71 GERMAN TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE, THE VHS LANG, FRITZ 1933 95 GERMAN MALOU VHS MEERAPFELE, JEANINE 1983 96 GERMAN TONIO KROGER VHS THIELE, ROLF 1964 97 GERMAN BARON MUNCHHAUSEN VHS VON BAKY, JOSEF 1943 99 GERMAN LOST HONOR OF KATHARINA BLUM, THE VHS SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 100 GERMAN THREEPENNY OPERA, THE VHS PABST, G.W. 1931 101 GERMAN JOYLESS STREET VHS PABST, G.W. 1925 102 GERMAN SIEGFRIED VHS LANG, FRITZ 1924 103 GERMAN TIN DRUM, THE DVD SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 105 GERMAN TIEFLAND VHS RIEFENSTAHL, LENI 1954 111 GERMAN BLICKKONTAKE (TO ACCOMPANY KONTAKE) VHS MCGRAW HILL 2000 127 GERMAN GERMANY AWAKE VHS LEISER, ERWIN 1968 129 GERMAN CAPTAIN FROM KOEPENIK, THE VHS KAUNTER, HELMUT 1956 167 GERMAN GERMANY IN AUTUMN VHS FASSBINDER, RANIER WERNER 1977 199 GERMAN PANDORA'S BOX VHS PABST, G.W. 1928 206 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 207 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 208 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 209 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 ROSEN, BOB AND ANDREA 211 GERMAN VIENNA 1900: ART, ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN VHS SIMON 1986 253 GERMAN CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, THE VHS WIENE, ROBERT 1919 265 GERMAN DAMALS VHS HANSEN, ROLF 1943 266 GERMAN GOLDENE STADT, DIE VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1942 267 GERMAN ZU NEUEN -

Das Reichsstudentenwerk Sozialbetreuung Von Studierenden Im Nationalsozialismus Eine Historische Studie Von Dr

Das Reichsstudentenwerk Sozialbetreuung von Studierenden im Nationalsozialismus Eine historische Studie von Dr. Christian Schölzel im Auftrag des Deutschen Studentenwerks 6 5 0 1 / 1 0 9 4 R n i l r e B . h c r A B Vorworte n n a m l e h c s r e H y a K : s o t Prof. Dr. Rolf-Dieter Postlep, Präsident Achim Meyer auf der Heyde, Generalsekretär o F Im Jahr 1921 – eine Zeit, in der die Studierenden in Deutschland Das Deutsche Studentenwerk als Verband der heute 57 Stu - immer noch stark unter den Folgen des Ersten Weltkriegs denten- und Studierendenwerke hat eine doppelte Mission: litten – wurde am 19.2. als unmittelbare Vorgängerinstitution sich für gute Rahmenbedingungen für die Studentenwerke des Deutschen Studentenwerks die „Wirtschaftshilfe der Deut - einzusetzen – und für die sozialpolitischen Belange der rund schen Studentenschaft e.V.“ gegründet, der Dachverband der 2,9 Millionen Studierenden in Deutschland. kurz zuvor etwa in Dresden, München, Bonn oder Tübingen entstandenen Selbsthilfeeinrichtungen bzw. Studentenhilfen. Dieser doppelte politische Auftrag hat seine Wurzeln im zivil - gesellschaftlichen, demokratischen Engagement von Studie - 2021 jährt sich die Gründung des Deutschen Studentenwerks renden und Lehrenden nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg. Diesen zum 100. Mal. Eine bruchlose Linie von 1921 bis 2021 gibt es Werten sind die Studenten- und Studierendenwerke bis heute allerdings nicht. Die Zeit der nationalsozialistischen Herrschaft zutiefst verpflichtet. stellt eine tiefe institutionelle Zäsur dar: Die Studentenwerke wurden gleichgeschaltet und jeglicher Autonomie beraubt; Mit dieser geschichtswissenschaftlichen Forschungsarbeit ihr Dachverband wurde instrumentalisiert und integriert ins werden nun erstmals die Jahre der nationalsozialistischen Gefüge der NS-Diktatur. -

Balancing Security and Liberty in Germany

Balancing Security and Liberty in Germany Russell A. Miller* INTRODUCTION Scholarly discourse over America’s national security policy frequently invites comparison with Germany’s policy.1 Interest in Germany’s national security jurisprudence arises because, like the United States, Germany is a constitutional democracy. Yet, in contrast to the United States, modern Germany’s historical encounters with violent authoritarian, anti-democratic, and terrorist movements have endowed it with a wealth of constitutional experience in balancing security and liberty. The first of these historical encounters – with National Socialism – provided the legacy against which Germany’s post-World War II constitutional order is fundamentally defined.2 The second encounter – with leftist domestic radicalism in the 1970s and 1980s – required the maturing German democracy to react to domestic terrorism.3 The third encounter – the security threat posed in the * Associate Professor of Law, Washington & Lee University School of Law ([email protected]); co-Editor-in-Chief, German Law Journal (http://www.germanlaw journal.com). This essay draws on material prepared for a forthcoming publication. See DONALD P. KOMMERS & RUSSELL A. MILLER, THE CONSTITUTIONAL JURISPRUDENCE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY (3rd ed., forthcoming 2011). It also draws on a previously published piece. See Russell A. Miller, Comparative Law and Germany’s Militant Democracy, in US NATIONAL SECURITY, INTELLIGENCE AND DEMOCRACY 229 (Russell A. Miller ed., 2008). The essay was written during my term as a Senior Fulbright Scholar at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and Public International Law in Heidelberg, Germany. 1. See, e.g., Jacqueline E. Ross, The Place of Covert Surveillance in Democratic Societies: A Comparative Study of the United States and Germany, 55 AM. -

Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination EDITED BY TARA FORREST Amsterdam University Press Alexander Kluge Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination Edited by Tara Forrest Front cover illustration: Alexander Kluge. Photo: Regina Schmeken Back cover illustration: Artists under the Big Top: Perplexed () Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn (paperback) isbn (hardcover) e-isbn nur © T. Forrest / Amsterdam University Press, All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustra- tions reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Alexander Kluge …and in memory of Miriam Hansen Table of Contents Introduction Editor’s Introduction Tara Forrest The Stubborn Persistence of Alexander Kluge Thomas Elsaesser Film, Politics and the Public Sphere On Film and the Public Sphere Alexander Kluge Cooperative Auteur Cinema and Oppositional Public Sphere: Alexander Kluge’s Contribution to G I A Miriam Hansen ‘What is Different is Good’: Women and Femininity in the Films of Alexander Kluge Heide -

Course Outline

Prof. Fatima Naqvi German 01:470:360:01; cross-listed with 01:175:377:01 (Core approval only for 470:360:01!) Fall 2018 Tu 2nd + 3rd Period (9:50-12:30), Scott Hall 114 [email protected] Office hour: Tu 1:10-2:30, New Academic Building or by appointment, Rm. 4130 (4th Floor) Classics of German Cinema: From Haunted Screen to Hyperreality Description: This course introduces students to canonical films of the Weimar, Nazi, post-war and post-wall period. In exploring issues of class, gender, nation, and conflict by means of close analysis, the course seeks to sensitize students to the cultural context of these films and the changing socio-political and historical climates in which they arose. Special attention will be paid to the issue of film style. We will also reflect on what constitutes the “canon” when discussing films, especially those of recent vintage. Directors include Robert Wiene, F.W. Murnau, Fritz Lang, Lotte Reiniger, Leni Riefenstahl, Alexander Kluge, Volker Schlöndorff, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Andreas Dresen, Christian Petzold, Jessica Hausner, Michael Haneke, Angela Schanelec, Barbara Albert. The films are available at the Douglass Media Center for viewing. Taught in English. Required Texts: Anton Kaes, M ISBN-13: 978-0851703701 Recommended Texts (on reserve at Alexander Library): Timothy Corrigan, A Short Guide to Writing about Film Rob Burns (ed.), German Cultural Studies Lotte Eisner, The Haunted Screen Sigmund Freud, Writings on Art and Literature Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler Anton Kaes, Shell Shock Cinema: Weimar Cinema and the Wounds of War Noah Isenberg, Weimar Cinema Gerd Gemünden, Continental Strangers Gerd Gemünden, A Foreign Affair: Billy Wilder’s American Films Sabine Hake, German National Cinema Béla Balász, Early Film Theory Siegfried Kracauer, The Mass Ornament Brad Prager, The Cinema of Werner Herzog Eric Ames, Ferocious Reality: Documentary according to Werner Herzog Eric Ames, Werner Herzog: Interviews N. -

The Image of Rebirth in Literature, Media, and Society: 2017 SASSI

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Society for the Academic Study of Social Imagery School of Communication 2017 The mI age of Rebirth in Literature, Media, and Society: 2017 SASSI Conference Proceedings Thomas G. Endres University of Northern Colorado, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/sassi Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, History Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Endres, Thomas G., "The mI age of Rebirth in Literature, Media, and Society: 2017 SASSI Conference Proceedings" (2017). Society for the Academic Study of Social Imagery. 1. http://digscholarship.unco.edu/sassi/1 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Communication at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Society for the Academic Study of Social Imagery by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMAGE OF REBIRTH in Literature, Media, and Society 2017 Conference Proceedings Society for the Academic Study of Social Imagery Edited by Thomas G. Endres Published by University of Northern Colorado ISSN 2572-4320 (online) THE IMAGE OF REBIRTH in Literature, Media, and Society Proceedings of the 2017 Conference of the Society for the Academic Study of Social Imagery March 2017 Greeley, Colorado Edited by Thomas G. Endres University of Northern Colorado Published -

Wenders Has Had Monumental Influence on Cinema

“WENDERS HAS HAD MONUMENTAL INFLUENCE ON CINEMA. THE TIME IS RIPE FOR A CELEBRATION OF HIS WORK.” —FORBES WIM WENDERS PORTRAITS ALONG THE ROAD A RETROSPECTIVE THE GOALIE’S ANXIETY AT THE PENALTY KICK / ALICE IN THE CITIES / WRONG MOVE / KINGS OF THE ROAD THE AMERICAN FRIEND / THE STATE OF THINGS / PARIS, TEXAS / TOKYO-GA / WINGS OF DESIRE DIRECTOR’S NOTEBOOK ON CITIES AND CLOTHES / UNTIL THE END OF THE WORLD ( CUT ) / BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB JANUSFILMS.COM/WENDERS THE GOALIE’S ANXIETY AT THE PENALTY KICK PARIS, TEXAS ALICE IN THE CITIES TOKYO-GA WRONG MOVE WINGS OF DESIRE KINGS OF THE ROAD NOTEBOOK ON CITIES AND CLOTHES THE AMERICAN FRIEND UNTIL THE END OF THE WORLD (DIRECTOR’S CUT) THE STATE OF THINGS BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Wim Wenders is cinema’s preeminent poet of the open road, soulfully following the journeys of people as they search for themselves. During his over-forty-year career, Wenders has directed films in his native Germany and around the globe, making dramas both intense and whimsical, mysteries, fantasies, and documentaries. With this retrospective of twelve of his films—from early works of the New German Cinema Alice( in the Cities, Kings of the Road) to the art-house 1980s blockbusters that made him a household name (Paris, Texas; Wings of Desire) to inquisitive nonfiction looks at world culture (Tokyo-ga, Buena Vista Social Club)—audiences can rediscover Wenders’s vast cinematic world. Booking: [email protected] / Publicity: [email protected] janusfilms.com/wenders BIOGRAPHY Wim Wenders (born 1945) came to international prominence as one of the pioneers of the New German Cinema in the 1970s and is considered to be one of the most important figures in contemporary German film. -

Art As Resistance by Langer

Dokument1 21.10.1998 02:20 Uhr Seite 1 Bernd Langer Art as Resistance Placats · Paintings· Actions · Texts from the Initiative Kunst und Kampf (Art and Struggle) KUNST UND KAMPF KuK Gesch engl 20.10.1998 22:48 Uhr Seite 1 Art as Resistance Paintings · Placats · Actions · Texts from the Initiative Kunst und Kampf (Art and Struggle) KuK Gesch engl 20.10.1998 22:48 Uhr Seite 2 Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Langer, Bernd: Art as resistance : placats, paintings, actions, texts from the Initiative Kunst und Kampf (art and struggle) ; Kunst und Kampf / Bernd Langer. [Transl. by: Anti-Fascist Forum]. - 1. Engl. ed. - Gšttingen : Aktiv-Dr. und Verl., 1998 Einheitssacht.: Kunst als Widerstand <engl.> ISBN 3-932210-03-4 Copyright © 1998 by Bernd Langer | Kunst und Kampf AktivDruck & Verlag Lenglerner Straße 2 37079 Göttingen Phone ++49-(5 51) 6 70 65 Fax ++49-(5 51) 63 27 65 All rights reserved Cover and Design, Composing, Scans: Martin Groß Internet: http://www.puk.de interactive web-community for politics and culture e-Mail: [email protected] Translated by: Anti-Fascist Forum P.O. Box 6326, Stn. A Toronto, Ontario M5W 1P7 Canada Internet: http://burn.ucsd.edu/~aff/ e-Mail: [email protected] first English edition, November 1998 Langer, Bernd: Art as Resistance Paintings · Placats · Actions · Texts from the Initiative Kunst und Kampf Internet: http://www.puk.de/kuk/ e-Mail: [email protected] ISBN 3-932210-03-4 KuK Gesch engl 20.10.1998 22:48 Uhr Seite 3 Bernd Langer Art as Resistance Paintings · Placats · Actions · Texts from the Initiative Kunst und Kampf (Art and Struggle) Kunst und Kampf KuK Gesch engl 20.10.1998 22:48 Uhr Seite 4 Table of contents 5 Foreword Part 1 Chapter I ..................................................................................... -

Warhol and Fassbinder

ARA OSTERWEIL IN NO HOME MOVIE (2015), Chantal Akerman records the decline of her mother, portraits Warhol ever made. As in many of his films, fiction dissolves into docu- a Polish Jewish Holocaust survivor, in what would turn out to be the last few years mentary, and Warhol’s mother is seen puttering around the kitchen in housecoat of both of their lives. The videography is amateur and the interactions between and babushka, talking incessantly in her nearly unintelligible Ruthenian accent, the two women quotidian: The film includes recordings of Skype sessions in which scrambling eggs for her new “husband” and the film’s crew, and, eventually, trying mother and daughter cannot think of much more to say to each other than “I love to teach Rheem how to properly iron a shirt. In other words, Julia is filmed doing you.” Yet in spite of the time they spend together, the unspeakable remains so, what one assumes were her usual tasks as Andy’s mother and default housekeeper, and the traumas of history resist revelation. For a film in which “nothing hap- here reimagined as matrimonial duties performed for her son’s lover. pens,” the intimacy is staggering. As if this arrangement weren’t Oedipal enough, the film’s title—Mrs. Warhol Akerman wasn’t the only filmmaker to cast her mother in a home movie that rather than Mrs. Warhola—suggests that Julia was essentially her son’s wife rather defies the conventions of both home and movies. Andy Warhol (1928–1987) and than her late husband’s. (Andy’s father, Ondrej Warhola, was a Czechoslovakian the German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder (1945–1982) both had intimate immigrant who, unlike his son, retained the final a in his name.) Furthermore, in relationships with their mothers that involved artistic collaboration; in Warhol’s her screen debut as a man-eater, Julia is implicitly made responsible for Ondrej’s case, the relationship also involved long periods of cohabitation. -

Storytelling and Survival in the 'Murderer's House'

Storytelling and Survival in the “Murderer’s House”: Gender, Voice(lessness) and Memory in Helma Sanders-Brahms’ Deutschland, bleiche Mutter by Rebecca Reed B.A., University of Victoria, 2003 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies © Rebecca Reed, 2009 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Storytelling and Survival in the “Murderer’s House”: Gender, Voice(lessness) and Memory in Helma Sanders-Brahms’ Deutschland, bleiche Mutter by Rebecca Reed B.A., University of Victoria, 2003 Supervisory Committee Dr. Helga Thorson, Supervisor (Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies) Dr. Charlotte Schallié, Departmental Member (Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies) Dr. Perry Biddiscombe, Outside Member (Department of History) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Helga Thorson, Supervisor (Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies) Dr. Charlotte Schallié, Departmental Member (Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies) Dr. Perry Biddiscombe, Outside Member (Department of History) ABSTRACT Helma Sanders-Brahms’ film Deutschland, bleiche Mutter is an important contribution to (West) German cinema and to the discourse of Vergangenheitsbewältigung or “the struggle to come to terms with the Nazi past” and arguably the first film of New German Cinema to take as its central plot a German woman’s gendered experiences of the Second World War and its aftermath. In her film, Deutschland, bleiche Mutter, Helma Sanders-Brahms uses a variety of narrative and cinematic techniques to give voice to the frequently neglected history of non- Jewish German women’s war and post-war experiences. -

Hanns Martin Schleyer-Stiftung Gemeinsam Mit Dem Bundespräsidenten Veröffentlichungen Der Hanns Martin Schleyer-Stiftung Band 91 Aus Anlass Des 40

Hanns Martin Schleyer-Stiftung gemeinsam mit dem Bundespräsidenten Veröffentlichungen der Hanns Martin Schleyer-Stiftung Band 91 Aus Anlass des 40. Todestages von Hanns Martin Schleyer zum Gedenken und Nachdenken: Die Freiheit verteidigen, die Demokratie stärken – eine bleibende Heraus forderung 18. Oktober 2017 im Schloss Bellevue Hanns Martin Schleyer-Stiftung gemeinsam mit dem Bundespräsidenten Herausgegeben von Barbara Frenz Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme. Ein Titeldaten- satz für die Publikation ist bei der Deutschen Bibliothek erhält- lich. ISBN: 978-3-9809206-8-1 © 2017 Hanns Martin Schleyer-Stiftung Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberschutzgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung der Hanns Martin Schleyer-Stiftung unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. Satz: Mazany – Werbekonzeption und Realisation, Düsseldorf Printed in Germany Inhalt Ansprache Bundespräsident Frank-Walter Steinmeier . 13 Grußwort Wilfried Porth . 23 Historische Einführung Stefan Aust . .29 Podiums- und Saaldiskussion . 39 Teilnehmende auf dem Podium: Stefan Aust Generalbundesanwalt Dr. Peter Frank Prof. Dr. Renate Köcher Prof. Dr. Andreas Rödder Moderation: Ina Baltes Worte zum Ende der Gedenkveranstaltung Bundespräsident Frank-Walter Steinmeier . 67 Anhang: Redaktionelle Nachbemerkung . 73 Veröffentlichungen der Hanns Martin Schleyer-Stiftung. 74 Leitung Barbara Frenz Hanns Martin Schleyer-Stiftung 7 Ansprache des Bundespräsidenten Bundespräsident Frank-Walter Steinmeier Lieber Hanns-Eberhard Schleyer, verehrte Familie Schleyer, verehrte Angehörige der Mordopfer der RAF, die Sie heute zu uns gekommen sind, Abgeordnete, verehrte Ministerpräsidenten Vogel und Biedenkopf, verehrter Herr Porth, Freunde und Förderer der Hanns Martin Schleyer-Stiftung, meine sehr verehrten Damen und Herren, Mord verjährt nicht. -

Die Schrecklichen Kinder: German Artists Confronting the Legacy of Nazism

Die Schrecklichen Kinder: German Artists Confronting the Legacy of Nazism A Division III by A. Elizabeth Berg May 2013 Chair: Sura Levine Members: Jim Wald and Karen Koehler 2 Table of Contents Introduction . 3 Heroic Symbols: Anselm Kiefer and the Nazi Salute . 13 And You Were Victorious After All: Hans Haacke and the Remnants of Nazism . 31 “The Right Thing to the Wrong People”: The Red Army Faction and Gerhard Richter’s 18. Oktober 1977 . 49 Conclusion . 79 Bibliography . 85 3 Introduction After the end of World War II, they were known as the Fatherless Generation. The children of postwar Germany—the children of Nazis—had lost their fathers in the war, though not always as a result of their death. For many members of this generation, even if their fathers did survive the war and perhaps even years in POW camps, they often returned irreparably physically and psychologically damaged. Once these children reached adolescence, many began to question their parents’ involvement with Nazism and their role during the war. Those who had participated in the atrocities of the war and those whose silence betrayed their guilt were problematic role models for their children, unable to fulfill their roles as parents with any moral authority.1 When these children came of age in the 1960s and entered universities, there was a major shift in the conversation about the war and the process of coming to terms with the past. The members of the postwar generation made themselves heard through large-scale protest and, eventually, violence. In this series of essays, I will look at the ways in which artists of this generation created work in response to their troubled history and the generational politics of the 1960s and 70s.