The Image of Rebirth in Literature, Media, and Society: 2017 SASSI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Write Yourself As the Antihero

Write yourself as the Antihero What is an Antihero and why do we love them? The best way to define an Antihero is to define what an anti-hero isn’t. An Antihero is not the traditional hero. A hero often has no flaws. Yes, Superman has his kryptonite, but if it were not for that, nothing would stop him. Antiheroes are more flawed than heroes simply because they are malleable and human. And, typically, their greatest flaw is what makes them relatable to readers and fun to write. Is an Antihero a Villain? Often people confuse the Antihero with the villain. Because Antiheroes might lie, cheat, murder, and steal, some say the line between the two and distinction might be subjective. Experts say that the stark difference between the Antihero and the villain is their end goal. Villains often just want to watch the world burn, or they are only out for themselves. Antiheroes usually have a justification for their choices or a noble objective that the reader can get on board with. You can make your character (YOU) both likeable and unlikeable by presenting a story that generates empathy and justifies their/your choices. Examples of Antiheroes The three types: Morally Grey Is Jack Sparrow a protagonist? (Why or why not?) Choices not favored by reader. Still likeable in his own right. Can be humorous if done right. Nonthreatening Character arc of Tyrian Lannister Low expectations from other characters. Little desire to be effectual. This changes over the course of the story arc. Villainous Walter White vs Lisbeth Salander Someone who does things what we cannot/ would not/might not do. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

The Female Monomyth in Twentyfirst Century Postapocalyptic Fiction

The Female Monomyth in TwentyFirst Century PostApocalyptic Fiction Written By: Amanda J. King For all the change that came about in the twentieth century, the surprising lack of adaptation by the film and television industry left many feeling disenfranchised with entertainment as a whole. As the nation slid into the twentyfirst century, riding the high of a prosperous decade, cinema and television alike were content to ride the coattails of success pioneered by previous generations. Sitcoms, police procedurals, overly theatrical soap operas, and daytime game shows dominated the market. Similarly, Hollywood continued to churn out unintelligible action films designed to stroke America’s inflated ego. Rippling muscles, broad shoulders, fists whiteknuckle tight gripping the handle of a sawedoff shotgun, these were the definitive attributes of a Hollywood hero, wrapped up neatly behind designer shades. Aside from the few genuinely well developed films and T.V. series, rote storytelling and machismo ideals permeated the boxoffice and our television sets. It wasn’t until tragedy befell our nation that we were forced to reassess our relative position in international politics and the world economy. For as often as life may imitate art, art is not impervious to lifelike inspiration. A new generation was once again forced overseas, leaving many women to hold down the fort. America was lost, for the time being, and the resultant restructuring of cinema conveyed this. Strong female leads weren’t unheard of ( i.e. Alien, Silence of the Lambs, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, etc ), but they most certainly were more often the exception to the rule. -

Ferguson Diss

PERMACULTURE AS FARMING PRACTICE AND INTERNATIONAL GRASSROOTS NETWORK: A MULTIDISCIPLINARY STUDY BY JEFFREY FERGUSON DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Crop Sciences in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Sarah Taylor Lovell, Chair Professor Michelle M. Wander Associate Professor Ashwini Chhatre Professor Thomas J. Bassett ABSTRACT Agroecology is a promising alternative to industrial agriculture, with the potential to avoid the negative social and ecological consequences of input-intensive production. Transitioning to agroecological production is, however, a complex project that requires action from all sectors of society – from producers and consumers, and from scientists and grassroots networks. Grassroots networks and movements are increasingly regarded as agents of change, with a critical role to play in agroecological transition as well as broader socio-environmental transformation. Permaculture is one such movement, with a provocative perspective on agriculture and human-environment relationships more broadly. Despite its relatively broad international distribution and high public profile, permaculture has remained relatively isolated from scientific research. This investigation helps to remedy that gap by assessing permaculture through three distinct projects. A systematic review offers a quantitative and qualitative assessment of the permaculture literature, -

BISCUIT SOCKS Instructions for Double-Pointed Needles

1/5 BISCUIT SOCKS By Isabelle - Fluffy Fibers Instructions for double-pointed needles I love DK socks. They knit up fast, and they are so cosy and warm to wear when staying home – which most of us are doing a lot of right now… At the close of this challenging year, I wanted to give you a little nugget of warmth and love, from my heart(h) to yours. I hope you enjoy knitting the Biscuit Socks for yourself, or perhaps as a comforting gift for a loved one. The light texture make the rounds addictive – just like a little pile of biscuits that we might enjoy going through as we knit and sip on our favourite warm beverage. I would be most grateful if you tagged me @fl uffyfibers and used #BiscuitSocks if you share your Biscuit Socks and WIPs on Instagram. Biscuit DK Socks – Fluffy Fibers Designs 2020 – all rights reserved 2/5 MATERIALS - 100 (150) g of sport to DK yarn. I - 1 set of 3.5-mm DPNs used 230 metres of Lang Super Soxx - 1 wool needle 6 ply for the smaller size. Some of - 1 removable stitch marker my test knitters needed as much as 300 metres. - 1 set of 3-mm DPNs FINISHED CIRCUMFERENCE: 21 (23,5) cms. GAUGE: 24 st : 10 cm in biscuit pattern ABBREVIATIONS: BOR: beginning of round p2tog: purl 2 stitches together CO: cast on RS: right side DPN: double-pointed needle sl: slip k: knit ssk: slip, slip, knit k2tog: k 2 stitches together w/: with p: purl WS: wrong side. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

The Struggle of Lower Class As Seen in Mad Max: Fury Road

THE STRUGGLE OF LOWER CLASS AS SEEN IN MAD MAX: FURY ROAD A GRADUATING PAPER Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Gaining the Bachelor Degree in English Literature By: Khoirur Rizal 10150051 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF ADAB AND CULTURAL SCIENCES STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SUNAN KALIJAGA YOGYAKARTA 2017 A FINAL PROJECT STATEMENT I certify that this graduating paper is definitely my own work. I am completely responsible for the content of this research. Other writer's opinions or findings included in the research are quoted or cited in accordance with ethical standards. Yo-eyakarta, 20 lunt 20 l7 The \\/nter Klioirur Rizal NIM. 10150051 KEMENTERIAN AGAMA UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SUNAN KALIJAGA FAKLTLTAS ADAB DAN ILMU BUDAYA J l. M a rsdaAd isuci pto Yogya ka rta 5 5 2 81 Te I p./Fa k. (O27 41513949 We b :http ://adab.uin-suka.ac.id E-mail : adab @ u i n-s u ka.ac. id NOTA DINAS Hal :Skripsi a.n. Khoirur Rizal Yth. Dekan Fakultas Adab dan Ilmu Budaya UIN Sunan Kalijaga Di Yogyakarta Assalamu' alaikum Wr. W. Setelah memeriksa, meneliti, dan memberikan arahan untuk perbaikan atas skripsi saudara: Nama KHOIRI]R RZAL NIM 101s0051 Prodi Sastra Inggrs Fakultas Adab dan IlmuBudaya Judul THE STRUGGLE Of,'LOWER CLASS AS SEEN IN MOVIE MAD MAX: FILRY ROAI) Saya menyatakan bahwa skripsi tersebut sudah dapat diajukan pada sidang Munaqosyah untukmemenuhi sebagian syaxat memperoleh gelar Sarjana Sasha Inggns. Atas perhatian yang diberikan, saya ucapkan terimakasih. Was s al amu' al aikum Wn Wb. Yogy, Pembimbi; NrP. 19760405 200901 1 016 1V THE STRUGGLE OF LOWER CLASS AS SEEN IN MAD MAX: FURY ROAD By: Khoirur Rizal ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to find out how lower classes rise against the upper class to achieve justice and equality. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

From Witchcraft to Pseudoscience

From Witchcraft to Pseudoscience Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England. By John Putnam Demos. Oxford University Press, New York, 1982. 543 pp. $29.95. Michael R. Dennett N SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY New England, in more cases than not, the I verdict in trials of individuals accused of being witches was "Not guilty."1 This is just one of the tidbits of information about the witch trials in early America found in John Demos's book, Entertaining Satan. It is rich in historic detail excavated from old court records at the cost of untold hours of research. Entertaining Satan is an important look into the past, and in particular it provides a view of how the paranormal was viewed three centuries ago. Demos gives the reader in-depth characterizations of some of the alleged witches (no light accom plishment in view of the incompleteness of available data). He also makes some effort to analyze the New England communities and their role in the events. It is is in the assessment of seventeenth-century New England and of witchcraft and how it relates to our day that this book fails. Discussing the idea of witchcraft and the trials, the author writes: "Our own culture accords a measure of tolerance to such conflicts; but in early New England the situation was probably quite different." He refers to the New England of this time as "premodern" and implies a connection between witchcraft and the premodern nature of the society. Although Demos never defines the premodern society, the implication is that it is different from a modern society. -

Symbiology (Page 172-178)

Symbiology (Page 172-178) The Agony of Life Sin-eaters remain conscious no matter what, and never suffer wound penalties from their pain. Geists revel in the pain after being unable to feel for so long. Polluted Blood Geists protect their Sin-eaters from poisons, toxins, and anything other than recreational drugs and alcohol. Sin-eaters add their Psyche to resist poisons and disease. Ectoplasmic Flesh Any time a Sin-eater takes damage, she can instead bulwark it, spending plasm to ignore damage for a scene. Put a dot in the box of any attack the Sin-eater bulwarks, and if she takes more damage, it goes over the box of the dot. This is limited by Plasm per turn limits, and is obviously supernatural, with milky white smoke rising from the wound as Plasm bleeds through clothing and ignores the wind. Last Resort Even denied healing or Plasm, a Sin-eater has the ability to use Death to harvest energy. Old Death, destroying a Memento, is a reflexive Resolve + Occult action that gives a Sin-eater Health equal to the destroyed Memento. New death, murder, requires a Sin-eater to sacrifice another human life, heals the Sin-eater fully, and immediately causes a Synergy loss. Resurrection Whenever a Sin-eater dies, her Geist returns her to life the next dawn or dusk (whichever comes first) with a caul over her eyes. This only gives a Sin-eater back their rightmost health box, costs two dots of permanent Synergy, and the caul reveals another person dying in the Sin-eater's stead, based on her Threshold. -

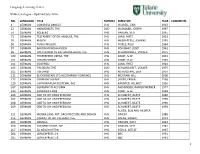

1 Language Learning Center Video Catalogue

Language Learning Center Video Catalogue – Updated July 2016 NO. LANGUAGE TITLE FORMAT DIRECTOR YEAR COMMENTS 4 GERMAN CONGRESS DANCES VHS CHARELL, ERIK 1932 22 GERMAN HARMONISTS, THE DVD VILSMAIER, JOSEPH 1997 54 GERMAN KOLBERG VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1945 71 GERMAN TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE, THE VHS LANG, FRITZ 1933 95 GERMAN MALOU VHS MEERAPFELE, JEANINE 1983 96 GERMAN TONIO KROGER VHS THIELE, ROLF 1964 97 GERMAN BARON MUNCHHAUSEN VHS VON BAKY, JOSEF 1943 99 GERMAN LOST HONOR OF KATHARINA BLUM, THE VHS SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 100 GERMAN THREEPENNY OPERA, THE VHS PABST, G.W. 1931 101 GERMAN JOYLESS STREET VHS PABST, G.W. 1925 102 GERMAN SIEGFRIED VHS LANG, FRITZ 1924 103 GERMAN TIN DRUM, THE DVD SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 105 GERMAN TIEFLAND VHS RIEFENSTAHL, LENI 1954 111 GERMAN BLICKKONTAKE (TO ACCOMPANY KONTAKE) VHS MCGRAW HILL 2000 127 GERMAN GERMANY AWAKE VHS LEISER, ERWIN 1968 129 GERMAN CAPTAIN FROM KOEPENIK, THE VHS KAUNTER, HELMUT 1956 167 GERMAN GERMANY IN AUTUMN VHS FASSBINDER, RANIER WERNER 1977 199 GERMAN PANDORA'S BOX VHS PABST, G.W. 1928 206 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 207 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 208 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 209 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 ROSEN, BOB AND ANDREA 211 GERMAN VIENNA 1900: ART, ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN VHS SIMON 1986 253 GERMAN CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, THE VHS WIENE, ROBERT 1919 265 GERMAN DAMALS VHS HANSEN, ROLF 1943 266 GERMAN GOLDENE STADT, DIE VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1942 267 GERMAN ZU NEUEN -

INFORMATION ISSUED by the ASSOCIATION of JEWISH REFUGEES in GREAT BRITAIN 8 FAIRFAX MANSIONS, Office and Consulting Hours: FINCHLEY ROAD (Comer Fairfax Rosdl, LONDON

Vol. XV No. 5 May, 1960 INFORMATION ISSUED BY THE ASSOCIATION OF JEWISH REFUGEES IN GREAT BRITAIN 8 FAIRFAX MANSIONS, Office and Consulting Hours: FINCHLEY ROAD (Comer Fairfax Rosdl, LONDON. N.W.3 Mondaylo Thursday 10 a.m.—I p.m. 3—6 p.m. Telephone: MAIda Vale 9096'7 (General Officel Friday 10 a.m.—l p.m. MAIda Vale 4449 (Employinent Agency and Socia) Services Dept.) ^i"* G. Reichmann hatte. Das Wiedergutmachungswerk, das der Herr Bundeskanzler mit der Hilfe seiner Parteifreunde und -gegner ins Leben gerufen hat, wird von den Menschen meines Kreises nicht nur wegen des DER FEIND IST DIE LAUHEIT materiellen Ergebnisses, sondern als Symbol guten Willens und ausgleichender Tat anerkannt. Und doch : trotz vieler hoffnungsvoUer Anfange Zur deutschen Situation von heute sind wir heute nicht zusammengekommen, um uns an Erfolgen zu freuen. Wir stehen vielmehr unter Wie wir bereits in der vorigen Nuininer berichteten, fandeu im Rahmen der " Woche dem Eindruck schwerer Riickschlage auf dem der Bruederlichkeit " in zahlreichen Staedten der Bundesrepublik und in West-Berlin Kund- rniihsamen Weg zueinander. Seien wir ganz offen : getungen statt. Die Redner waren in den meisten FaeUen fuehrende nichtjuedische sie kamen nicht unerwartet. Unerwar.tet konnten Persoenlichkeiten des oeffentlichen Lebens in Deutschland. Das folgende, gekuerzt wieder sie eigentlich nur von dem empfunden werden, gegebene Referat. das Dr. Eva G. Reichmann (London) auf der Kundgebung in Bonn hielt, der mit den Verhaltnissen in Deutschland wenig duerfte fuer unsere Leser deshalb von besonderem Interesse sein, weil es das Problem in vertraut war. Wer wie meine Mitarbeiter von der einer Weise darstellt.