Reviewed Scott Dissertation Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: August 6th, 2007 I, __________________Julia K. Baker,__________ _____ hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in: German Studies It is entitled: The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life-Writing and Documentary Film This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Katharina Gerstenberger Dr. Sara Friedrichsmeyer Dr. Todd Herzog The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life-Writing and Documentary Film A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) In the Department of German Studies Of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julia K. Baker M.A., Bowling Green State University, 2000 M.A., Karl Franzens University, Graz, Austria, 1998 Committee Chair: Katharina Gerstenberger ABSTRACT “The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life- Writing and Documentary Film” is a study of the literary responses of writers who were Jewish children in hiding and exile during World War II and of documentary films on the topic of refugee children and children in exile. The goal of this dissertation is to investigate the relationships between trauma, memory, fantasy and narrative in a close reading/viewing of different forms of Jewish life-writing and documentary film by means of a scientifically informed approach to childhood trauma. Chapter 1 discusses the reception of Binjamin Wilkomirski’s Fragments (1994), which was hailed as a paradigmatic traumatic narrative written by a child survivor before it was discovered to be a fictional text based on the author’s invented Jewish life-story. -

Post-1990 Screen Memories: How East and West German Cinema Remembers the Third Reich and the Holocaust

German Life and Letters 59:2 April 2006 0016–8777 (print); 1468–0483 (online) POST-1990 SCREEN MEMORIES: HOW EAST AND WEST GERMAN CINEMA REMEMBERS THE THIRD REICH AND THE HOLOCAUST DANIELA BERGHAHN ABSTRACT The following article examines the contribution of German feature films about the Third Reich and the Holocaust to memory discourse in the wake of German unifi- cation. A comparison between East and West German films made since the 1990s reveals some startling asymmetries and polarities. While East German film-makers, if they continued to work in Germany’s reunified film industry at all, made very few films about the Third Reich, West German directors took advantage of the recent memory boom. Whereas films made by East German directors, such as Erster Verlust and Der Fall Ö, suggest, in liberating contradiction to the anti-fascist interpretation of history, that East Germany shared the burden of guilt, West German productions subscribe to the normalisation discourse that has gained ideological hegemony in the East-West-German memory contest since unification. Films such as Aimée & Jaguar and Rosenstraße construct a memory of the past that is no longer encumbered by guilt, principally because the relationship between Germans and Jews is re-imag- ined as one of solidarity. As post-memory films, they take liberties with the trau- matic memory of the past and, by following the generic conventions of melodrama, family saga and European heritage cinema, even lend it popular appeal. I. FROM DIVIDED MEMORY TO COMMON MEMORY Many people anticipated that German reunification would result in a new era of forgetfulness and that a line would be drawn once and for all under the darkest chapter of German history – the Third Reich and the Holocaust. -

Barbara Hammer, 70 Years Old, Hands the Camera to Gina Carducci, a Young Queer Film- Maker

Generations is a film about mentoring and passing on the tradi- tion of personal experimental filmmaking. Barbara Hammer, 70 years old, hands the camera to Gina Carducci, a young queer film- maker. Shooting during the last days of Astroland at Coney Is- land, New York, the filmmakers find that the inevitable fact of ageing echoes in the architecture of the amusement park and in the emulsion of the film medium itself. Editing completely sep- arately both picture and sound, the filmmakers join their films in the middle when they’ve finished, making a true generational and experimental experiment. In a time when digital dominates the art domain, a DIY aesthet- ic is embraced by Gina Carducci, a young thirty-year-old filmmak- er who hand processes 16mm film and a seventy-year-old pioneer of queer experimental cinema, Barbara Hammer. Hammer invites Carducci to collaborate on a new film, Generations. Barbara Hammer Celebrating Hammer’s spontaneous shooting style and dense ed- Maya Deren’s Sink iting montage with Carducci’s studied cinematography, the two filmmakers, generations apart in age, shoot the last days of Astro- land in Coney Island, New York. The aged but vibrant amusement Eine Hommage an die Mutter des amerikanischen Avantgarde- park, characteristic of the 70-year-old Hammer, is a fitting envi- films. Der Film beschwört durch Gespräche mit WeggefährtInnen ronment for the photoplay of the two Bolex filmmakers. und ZeitgenossInnen den Geist einer überlebensgroßen Person. Teiji Itos Familie, Carolee Schneemann und Judith Malvina schwe- Inspired by the revolutionary Shirley Clarke film,Bridges Go ben durch Derens Wohnorte und erinnern sich an kleinste Details Round (1953), where Clarke printed the same footage twice us- der architektonischen und persönlichen Innenräume. -

A QUIET EVENING of DANCE by WILLIAM FORSYTHE Pääyhteistyökumppanit / Partners / Partners Sponsorit / Sponsors / Sponsorer Thu–Fri 22.–23.8

©Bill Cooper #juhlaviikot #helsinkifestival The visit is produced in collaboration with Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation and Dance House Helsinki. A Sadler´s Wells London Production JANE and AATOS ERKKO FOUNDATION A QUIET EVENING OF DANCE BY WILLIAM FORSYTHE Pääyhteistyökumppanit / Partners / Partners Sponsorit / Sponsors / Sponsorer Thu–Fri 22.–23.8. Finnish National Opera and ballet, Almi Hall PRODUCTION CREDITS Dancers: Brigel Gjoka, Jill Johnson, Christopher Roman (understudied by Brit Rodemund in Helsinki), Parvaneh Scharafali, Riley Watts, Rauf “RubberLegz“ Yasit, Ander Zabala Composer/Music: Morton Feldman, Nature Pieces from Piano No.1. From, First Recordings (1950s) – The Turfan Ensemble, Philipp Vandré © Mode (for Epilogue) A Sadler’s Wells London Production Composer/Music: Jean‐Philippe Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie: Ritournelle, from A Quiet Evening of Dance Une Symphonie Imaginaire, Marc Minkowski & Les Musiciens du Louvre © 2005 By William Forsythe Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Berlin (for Seventeen/Twenty One) and Lighting Design: Tanja Rühl and William Forsythe Brigel Gjoka, Jill Johnson, Christopher Roman, Parvaneh Scharafali, Riley Watts, Rauf “RubberLegz” Yasit and Ander Zabala. Costume Design: Dorothee Merg and William Forsythe Co-produced with Théâtre de la Ville, Paris; Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris; Festival d’Automne Sound Design: Niels Lanz à Paris; Festival Montpellier Danse 2019; Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg; The Shed, New York; Onassis Cultural Centre, Athens; deSingel international arts campus, Antwerp. For Sadler’s Wells Artistic Director & Chief Executive: Alistair Spalding CBE First performed at Sadler’s Wells London on 4 October 2018. Executive Producer: Suzanne Walker Head of Producing & Touring: Bia Oliveira Winner of the FEDORA - VAN CLEEF & ARPELS Prize for Ballet 2018. -

Über Gegenwartsliteratur About Contemporary Literature

Leseprobe Über Gegenwartsliteratur Interpretationen und Interventionen Festschrift für Paul Michael Lützeler zum 65. Geburtstag von ehemaligen StudentInnen Herausgegeben von Mark W. Rectanus About Contemporary Literature Interpretations and Interventions A Festschrift for Paul Michael Lützeler on his 65th Birthday from former Students Edited by Mark W. Rectanus AISTHESIS VERLAG ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Bielefeld 2008 Abbildung auf dem Umschlag: Paul Klee: Roter Ballon, 1922, 179. Ölfarbe auf Grundierung auf Nesseltuch auf Karton, 31,7 x 31,1 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. © VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn 2008 Bibliographische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. © Aisthesis Verlag Bielefeld 2008 Postfach 10 04 27, D-33504 Bielefeld Satz: Germano Wallmann, www.geisterwort.de Druck: docupoint GmbH, Magdeburg Alle Rechte vorbehalten ISBN 978-3-89528-679-7 www.aisthesis.de Inhaltsverzeichnis/Table of Contents Danksagung/Acknowledgments ............................................................ 11 Mark W. Rectanus Introduction: About Contemporary Literature ............................... 13 Leslie A. Adelson Experiment Mars: Contemporary German Literature, Imaginative Ethnoscapes, and the New Futurism .......................... 23 Gregory W. Baer Der Film zum Krug: A Filmic Adaptation of Kleist’s Der zerbrochne Krug in the GDR ......................................................... -

Annual Report 2019 Contents

Annual Report 2019 Contents 4 Foreword 93 Report of the Supervisory Board 6 Executive Board 102 Consolidated Financial Statements 103 Consolidated Statement of 8 The Axel Springer share Financial Position 10 Combined Management Report 105 Consolidated Income Statement 106 Consolidated Statement of 13 Fundamentals of the Axel Springer Group Comprehensive Income 24 Economic Report 107 Consolidated Statement of 44 Economic Position of Axel Springer SE Cash Flows 48 Report on risks and opportunities 108 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 60 Forecast Report 109 Consolidated Segment Report 71 Disclosures and explanatory report on the Executive Board pursuant to takeover law 110 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 77 Corporate Governance Report 180 Responsibility Statement 181 Independent Auditor’s Report 187 Boards 2 Group Key Figures in € millions Change yoy 2019 2018 Group Revenues – 2.2 % 3,112.1 3,180.7 Digital revenue share1) 73.3 % 70.6 % 2) EBITDA, adjusted – 14.5 % 630.6 737.9 EBITDA margin, adjusted2) 20.3 % 23.2 % 2) EBIT, adjusted – 21.5 % 414.5 527.9 EBIT margin, adjusted 2) 13.3 % 16.6 % Net income – 35.4 % 134.6 208.4 2) Net income, adjusted – 21.5 % 263.7 335.7 Segments Revenues Classifieds Media 0.1 % 1,213.8 1,212.5 News Media – 4.4 % 1,430.9 1,496.2 Marketing Media 0.8 % 421.5 418.3 Services/Holding – 14.4 % 46.0 53.7 EBITDA, adjusted2) Classifieds Media – 3.8 % 468.4 487.2 News Media – 39.3 % 138.5 228.2 Marketing Media 20.3 % 107.8 89.6 Services/Holding − – 84.1 – 67.0 EBIT, adjusted2) Classifieds Media – 7.1 % 377.9 406.7 News Media – 54.4 % 72.1 158.2 Marketing Media 26.1 % 83.3 66.0 Services/Holding − – 118.6 – 103.0 Liquidity and financial position 2) Free cash flow (FCF) – 38.1 % 214.6 346.9 2) 3) FCF excl. -

Wenn Ki, Dann Feministisch Impulse Aus Wissenschaft Und Aktivismus

WENN KI, DANN FEMINISTISCH IMPULSE AUS WISSENSCHAFT UND AKTIVISMUS Hrsg. von netzforma* e.V. Berlin 2020 • Wenn KI, dann feministisch — Impulse aus Wissenschaft und Aktivismus Hrsg. von netzforma* e.V. — Berlin 2020 • DIE GESCHICHTE MEINER SCHRIFT Zu Beginn des Jahres entdeckte meine Mutter eine neue Leiden- schaft: Sticken. Sie hatte schon vorher Freude an kreativen Praktiken gehabt (wie Weben und Stricken). In ihrer neuen Aktivität fand sie etwas befriedigendes, was sie sehr er- füllt. Ihre ersten Stickereien waren Buchstaben, vor allem aus dem Sajou-Alphabet. Als ich die sah, kam mir eine Idee. Gemeinsam dachten wir über eine fruchtbare Zusammen- arbeit nach, die unsere beiden jeweiligen Hobbys vereinen könnte. Was wäre, wenn sie meine eigenen Schriften stickte? Um diese Idee umzusetzen, entwickelte ich für meine Schrift Arthemys Display Light eine neue Version, die es meiner Mutter ermöglichte, die Formen auf ein spezielles Gewebe (namens Aïda) zu übertragen. Dieser Prozess erfordert eine binäre Sprache, genau wie Pixel auf einem Computer. Die Buchstaben werden also Punkt für Punkt gedacht und akribisch zusammengesetzt. Das geht weg von dem Ge- danken einer vektorisierten Form, die nur durch ihre Umrisse definiert wird. Vielmehr muss die Form in ihrer gesamten Fläche aufgebaut werden, wie mit Legosteinen! Auf dieser Grundlage konnte meine Mutter die verschiedenen Buch- staben bauen, indem sie einfach dem Raster des Gewebes folgte. Sicherlich war dieser Prozess ziemlich aufwendig und verlangte eine Menge Geduld ab, aber meine Mutter -

14Annual Report Contents

14Annual Report Contents 4 Foreword 78 Report of the Supervisory Board 6 Executive Board 86 Consolidated Financial Statements 87 Responsibility Statement 8 The Axel Springer share 88 Auditor’s Report 89 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 10 Combined Management Report 91 Consolidated Statement of 12 Fundamentals of the Axel Springer Group Comprehensive Income 22 Economic report 92 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 41 Economic position of Axel Springer SE 93 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 44 Events after the reporting date 94 Consolidated Segment Report 45 Report on risks and opportunities 95 Notes to the Consolidated 56 Forecast report Financial Statements 61 Disclosures and explanatory report of the Executive Board pursuant to takeover law 158 Boards 65 Corporate Governance Report Group Key Figures Continuing operations in € millions Change yoy 2014 2013 2012 Group Total revenues 8.4 % 3,037.9 2,801.4 2,737.3 Digital media revenues share 53.2 % 47.5 % 42.4 % 1) EBITDA 11.6 % 507.1 454.3 498.8 1) EBITDA margin 16.7 % 16.2 % 18.2 % 2) Digital media EBITDA share 72.1 % 62.0 % 49.4 % 3) EBIT 9.7 % 394.6 359.7 413.6 Consolidated net income 31.9 % 235.7 178.6 190.7 3) Consolidated net income, adjusted 9.3 % 251.2 229.8 258.6 Segments Revenues Paid Models 2.6 % 1,561.4 1,521.5 1,582.9 Marketing Models 10.8 % 794.1 716.5 662.8 Classified Ad Models 27.2 % 512.0 402.6 330.2 Services/Holding 6.1 % 170.5 160.8 161.4 EBITDA1) Paid Models – 2.4 % 244.2 250.1 301.8 Marketing Models 6.0 % 109.7 103.4 98.1 Classified Ad Models -

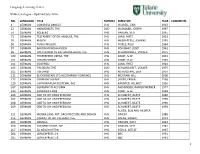

1 Language Learning Center Video Catalogue

Language Learning Center Video Catalogue – Updated July 2016 NO. LANGUAGE TITLE FORMAT DIRECTOR YEAR COMMENTS 4 GERMAN CONGRESS DANCES VHS CHARELL, ERIK 1932 22 GERMAN HARMONISTS, THE DVD VILSMAIER, JOSEPH 1997 54 GERMAN KOLBERG VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1945 71 GERMAN TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE, THE VHS LANG, FRITZ 1933 95 GERMAN MALOU VHS MEERAPFELE, JEANINE 1983 96 GERMAN TONIO KROGER VHS THIELE, ROLF 1964 97 GERMAN BARON MUNCHHAUSEN VHS VON BAKY, JOSEF 1943 99 GERMAN LOST HONOR OF KATHARINA BLUM, THE VHS SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 100 GERMAN THREEPENNY OPERA, THE VHS PABST, G.W. 1931 101 GERMAN JOYLESS STREET VHS PABST, G.W. 1925 102 GERMAN SIEGFRIED VHS LANG, FRITZ 1924 103 GERMAN TIN DRUM, THE DVD SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 105 GERMAN TIEFLAND VHS RIEFENSTAHL, LENI 1954 111 GERMAN BLICKKONTAKE (TO ACCOMPANY KONTAKE) VHS MCGRAW HILL 2000 127 GERMAN GERMANY AWAKE VHS LEISER, ERWIN 1968 129 GERMAN CAPTAIN FROM KOEPENIK, THE VHS KAUNTER, HELMUT 1956 167 GERMAN GERMANY IN AUTUMN VHS FASSBINDER, RANIER WERNER 1977 199 GERMAN PANDORA'S BOX VHS PABST, G.W. 1928 206 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 207 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 208 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 209 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 ROSEN, BOB AND ANDREA 211 GERMAN VIENNA 1900: ART, ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN VHS SIMON 1986 253 GERMAN CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, THE VHS WIENE, ROBERT 1919 265 GERMAN DAMALS VHS HANSEN, ROLF 1943 266 GERMAN GOLDENE STADT, DIE VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1942 267 GERMAN ZU NEUEN -

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples Mittelalter (1150- Wolfram von Eschenbach Epik Parzival (1200/1210) 1450) Gottfried von Straßburg Tristan (ca. 1210) Hartmann von Aue Der arme Heinrich (ca. 1195) Johannes von Tepl Der Ackermann aus Böhmen (ca. 1400) Walther von der Vogelweide Lieder, Oskar von Wolkenstein Minnelyrik, Spruchdichtung Gedichte Renaissance Martin Luther Prosa Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen (1530) (1400-1600) Von der Freyheit eynis Christen Menschen (1521) Historia von D. Johann Fausten (1587) Das Volksbuch vom Eulenspiegel (1515) Der ewige Jude (1602) Sebastian Brant Das Narrenschiff (1494) Barock (1600- H.J.C. von Grimmelshausen Prosa Der abenteuerliche Simplizissimus Teutsch (1669) 1720) Schelmenroman Martin Opitz Lyrik Andreas Gryphius Paul Fleming Sonett Christian v. Hofmannswaldau Paul Gerhard Aufklärung (1720- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Prosa Fabeln 1785) Christian Fürchtegott Gellert Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Drama Nathan der Weise (1779) Bürgerliches Emilia Galotti (1772) Trauerspiel Miss Sara Samson (1755) Lustspiel Minna von Barnhelm oder das Soldatenglück (1767) 2 Sturm und Drang Johann Wolfgang Goethe Prosa Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (1774) (1767-1785) Johann Gottfried Herder Von deutscher Art und Kunst (selections; 1773) Karl Philipp Moritz Anton Reiser (selections; 1785-90) Sophie von Laroche Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim (1771/72) Johann Wolfgang Goethe Drama Götz von Berlichingen (1773) Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz Der Hofmeister oder die Vorteile der Privaterziehung (1774) -

View Recent MA Theses, Exams, and Projects

Department of Women’s Studies Masters Thesis Topics Thesis: Politicizing the Woman’s Body: Incentivizing Childbirth to Rebuild Hungarian Kelsey Rosendale Nationalism (Spring 2021) Exam: Feminist Political and Epistemic Engagements with Menstruation and Meat- Rashanna Lee Eating (Spring 2021) Thesis: Patch Privilege: A Queer Feminist Autoethnography of Lifeguarding (Spring Asako Yonan 2021) Thesis: A Feminist Epistemological Evaluation of Comparative Cognition Research Barbara Perez (Spring 2021) Thesis: Redefining Burden: A Mother and Daughter’s Navigation of Alzheimer’s Anna Buckley Dementia (Spring 2021) Project: Feminist Dramaturgy and Analysis of San Diego State’s Fall 2020 Production of Emily Sapp Two Lakes, Two Rivers (Spring 2021) Thesis: Living as Resistance: The Limits of Huanization and (Re)Imagining Life-Making Amanda Brown as Rebellion for Black Trans Women in Pose (Fall 2020) Thesis: More than and Image: A Feminist Analysis of Childhood, Values, and Norms in Ariana Aritelli Children’s Clothing Advertisements at H&M (Spring 2020) Alexandra-Grissell H. Thesis: A Queer of Color Materialista Praxis (Spring 2020) Gomez Thesis: Centers of Inclusion? Trans* and Non-Binary Inclusivity in California State Lori Loftin University Women’s Centers (Spring 2020) Rogelia Y. Mata- Thesis: First-Generation College Latinas’ Self-Reported Reasons for Joining a Latina- Villegas Focused Sorority (Spring 2020) Thesis: The Rise of Genetic Genealogy: A Queer and Feminist Analysis of Finding Your Kerry Scroggie Roots Spring 2020) Yazan Zahzah Thesis: -

Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination EDITED BY TARA FORREST Amsterdam University Press Alexander Kluge Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination Edited by Tara Forrest Front cover illustration: Alexander Kluge. Photo: Regina Schmeken Back cover illustration: Artists under the Big Top: Perplexed () Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn (paperback) isbn (hardcover) e-isbn nur © T. Forrest / Amsterdam University Press, All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustra- tions reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Alexander Kluge …and in memory of Miriam Hansen Table of Contents Introduction Editor’s Introduction Tara Forrest The Stubborn Persistence of Alexander Kluge Thomas Elsaesser Film, Politics and the Public Sphere On Film and the Public Sphere Alexander Kluge Cooperative Auteur Cinema and Oppositional Public Sphere: Alexander Kluge’s Contribution to G I A Miriam Hansen ‘What is Different is Good’: Women and Femininity in the Films of Alexander Kluge Heide