Warhol and Fassbinder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andy Warhol From

Andy Warhol From “THE HOUSE THAT went to TOWN” 8 February - 9 March 2019 I. Andy Warhol “Dancing Sprites”, ca. 1953 ink and watercolor on paper 73.7 x 29.5 cm (framed: 92.7 x 48.4 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1953/23 Andy Warhol “Sprite Acrobats”, ca. 1956 ink on paper, double-sided 58.5 x 73.5 cm (framed: 92.4 x 77.5 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1956/08 Andy Warhol “Sprite Figures Kissing”, ca. 1951 graphite on paper 14.3 x 21.6 cm (framed: 32.2 x 39.5 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1951/01 Warhol used this motif in several illustrations from the early 1950s: for an anonymous article entitled “Romantic Possession” (publication unknown, c. 1950) and for Weare Holbrook’s “Women – What To Do With Them”, Park East (March 1952), p. 26. See Paul Maréchal, Andy Warhol: The Complete Commissioned Magazine Work, 1948- 1987: A Catalogue Raisonné (Munich: Prestel, 2014), pp. 30, 50. Andy Warhol “Female Sprite”, ca. 1954 graphite on paper, double-sided 27.9 x 21.6 cm (framed: 46 x 39.7 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1954/05 Andy Warhol “Sprite Head with Feet”, ca. 1953 ink on paper 27.9 x 21.5 cm (framed: 46 x 39.7 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1953/24 Andy Warhol “Sprite Portrait with Shoes”, ca. 1953 ink on paper 27.8 x 21.5 cm (framed: 46 x 39.7 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1953/25 II. Andy Warhol “The House That Went To Town”, 1952-1953 graphite, ink and tempera on paper 27.7 x 21.7 cm (framed: 46 x 39.7 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1956/25 The likely prototype for Warhol and Corkie’s “THE HOUSE THAT went to TOWN” is Virginia Lee Burton’s celebrated children’s book The Little House, first published in 1942. -

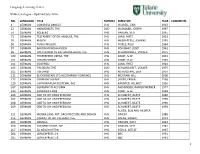

1 Language Learning Center Video Catalogue

Language Learning Center Video Catalogue – Updated July 2016 NO. LANGUAGE TITLE FORMAT DIRECTOR YEAR COMMENTS 4 GERMAN CONGRESS DANCES VHS CHARELL, ERIK 1932 22 GERMAN HARMONISTS, THE DVD VILSMAIER, JOSEPH 1997 54 GERMAN KOLBERG VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1945 71 GERMAN TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE, THE VHS LANG, FRITZ 1933 95 GERMAN MALOU VHS MEERAPFELE, JEANINE 1983 96 GERMAN TONIO KROGER VHS THIELE, ROLF 1964 97 GERMAN BARON MUNCHHAUSEN VHS VON BAKY, JOSEF 1943 99 GERMAN LOST HONOR OF KATHARINA BLUM, THE VHS SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 100 GERMAN THREEPENNY OPERA, THE VHS PABST, G.W. 1931 101 GERMAN JOYLESS STREET VHS PABST, G.W. 1925 102 GERMAN SIEGFRIED VHS LANG, FRITZ 1924 103 GERMAN TIN DRUM, THE DVD SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 105 GERMAN TIEFLAND VHS RIEFENSTAHL, LENI 1954 111 GERMAN BLICKKONTAKE (TO ACCOMPANY KONTAKE) VHS MCGRAW HILL 2000 127 GERMAN GERMANY AWAKE VHS LEISER, ERWIN 1968 129 GERMAN CAPTAIN FROM KOEPENIK, THE VHS KAUNTER, HELMUT 1956 167 GERMAN GERMANY IN AUTUMN VHS FASSBINDER, RANIER WERNER 1977 199 GERMAN PANDORA'S BOX VHS PABST, G.W. 1928 206 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 207 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 208 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 209 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 ROSEN, BOB AND ANDREA 211 GERMAN VIENNA 1900: ART, ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN VHS SIMON 1986 253 GERMAN CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, THE VHS WIENE, ROBERT 1919 265 GERMAN DAMALS VHS HANSEN, ROLF 1943 266 GERMAN GOLDENE STADT, DIE VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1942 267 GERMAN ZU NEUEN -

Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination EDITED BY TARA FORREST Amsterdam University Press Alexander Kluge Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination Edited by Tara Forrest Front cover illustration: Alexander Kluge. Photo: Regina Schmeken Back cover illustration: Artists under the Big Top: Perplexed () Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn (paperback) isbn (hardcover) e-isbn nur © T. Forrest / Amsterdam University Press, All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustra- tions reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Alexander Kluge …and in memory of Miriam Hansen Table of Contents Introduction Editor’s Introduction Tara Forrest The Stubborn Persistence of Alexander Kluge Thomas Elsaesser Film, Politics and the Public Sphere On Film and the Public Sphere Alexander Kluge Cooperative Auteur Cinema and Oppositional Public Sphere: Alexander Kluge’s Contribution to G I A Miriam Hansen ‘What is Different is Good’: Women and Femininity in the Films of Alexander Kluge Heide -

Course Outline

Prof. Fatima Naqvi German 01:470:360:01; cross-listed with 01:175:377:01 (Core approval only for 470:360:01!) Fall 2018 Tu 2nd + 3rd Period (9:50-12:30), Scott Hall 114 [email protected] Office hour: Tu 1:10-2:30, New Academic Building or by appointment, Rm. 4130 (4th Floor) Classics of German Cinema: From Haunted Screen to Hyperreality Description: This course introduces students to canonical films of the Weimar, Nazi, post-war and post-wall period. In exploring issues of class, gender, nation, and conflict by means of close analysis, the course seeks to sensitize students to the cultural context of these films and the changing socio-political and historical climates in which they arose. Special attention will be paid to the issue of film style. We will also reflect on what constitutes the “canon” when discussing films, especially those of recent vintage. Directors include Robert Wiene, F.W. Murnau, Fritz Lang, Lotte Reiniger, Leni Riefenstahl, Alexander Kluge, Volker Schlöndorff, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Andreas Dresen, Christian Petzold, Jessica Hausner, Michael Haneke, Angela Schanelec, Barbara Albert. The films are available at the Douglass Media Center for viewing. Taught in English. Required Texts: Anton Kaes, M ISBN-13: 978-0851703701 Recommended Texts (on reserve at Alexander Library): Timothy Corrigan, A Short Guide to Writing about Film Rob Burns (ed.), German Cultural Studies Lotte Eisner, The Haunted Screen Sigmund Freud, Writings on Art and Literature Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler Anton Kaes, Shell Shock Cinema: Weimar Cinema and the Wounds of War Noah Isenberg, Weimar Cinema Gerd Gemünden, Continental Strangers Gerd Gemünden, A Foreign Affair: Billy Wilder’s American Films Sabine Hake, German National Cinema Béla Balász, Early Film Theory Siegfried Kracauer, The Mass Ornament Brad Prager, The Cinema of Werner Herzog Eric Ames, Ferocious Reality: Documentary according to Werner Herzog Eric Ames, Werner Herzog: Interviews N. -

The Image of Rebirth in Literature, Media, and Society: 2017 SASSI

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Society for the Academic Study of Social Imagery School of Communication 2017 The mI age of Rebirth in Literature, Media, and Society: 2017 SASSI Conference Proceedings Thomas G. Endres University of Northern Colorado, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/sassi Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, History Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Endres, Thomas G., "The mI age of Rebirth in Literature, Media, and Society: 2017 SASSI Conference Proceedings" (2017). Society for the Academic Study of Social Imagery. 1. http://digscholarship.unco.edu/sassi/1 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Communication at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Society for the Academic Study of Social Imagery by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMAGE OF REBIRTH in Literature, Media, and Society 2017 Conference Proceedings Society for the Academic Study of Social Imagery Edited by Thomas G. Endres Published by University of Northern Colorado ISSN 2572-4320 (online) THE IMAGE OF REBIRTH in Literature, Media, and Society Proceedings of the 2017 Conference of the Society for the Academic Study of Social Imagery March 2017 Greeley, Colorado Edited by Thomas G. Endres University of Northern Colorado Published -

August 2018 Vol

August 2018 vol. 41 no. 7 Providing fitness and community for individuals and families through physical, educational, cultural, and social programs th 7 Annual Czech that Film! Bringing the Best New Czech Films to North America Presented in collaboration with the Consulate General UPCOMING EVENTS of the Czech Republic in Los Angeles, Czech That Film is a series showcasing the best of Czech cinema. 2018 September Slovo Deadline It is committed to exhibiting films that not only expose August1,2018 participants to Czech culture, but also enlighten audiences, bring people together, and present inspired Board of Trustees Meeting entertainment for all. 100 YEARS August8,7p.m. OF CZECHOSLOVAK Supporting the film series locally are Czech and CINEMA Slovak Sokol Minnesota, Czech and Slovak Cultural Slovak Architect for all Center of Minnesota, Czech & Slovak School Twin Seasons Lecture Cities, Marshall Toman, Honorary Czech Consul M. L. Kucera, plus others. RecognizingDušanJurkovič Friday, August 24, 9:30 p.m. 8 HEADS OF MADNESS / 8 HLAV ŠÍLENSTVÍ . Directed August11,11a.m. by Marta Nováková, 2017, 107 minutes. Follow the life of the talented Russian poet Anna Barkova (1906–1976), who spent twenty-two years of her life in the Gulag. Board of Directors Meeting Saturday, August 25, 4:00 p.m. MILADA / MILADA . Directed by David Mrnka, 2017, 124 minutes. This historical drama is based on the true story of Milada Horáková, a woman August16,7p.m. executed on the basis of fabricated charges of conspiracy and treason in a political show trial by the communist regime in the former Czechoslovakia. -

William Morris & Andy Warhol

MODERN ART EVENTS OXFORD THE YARD TOURS The Factory Floor Wednesday 7 January, 1pm Wednesday to Saturday, 12-5pm, weekly Sally Shaw, Head of Programme at Modern Art Oxford For the duration of Love is Enough, the Yard will discusses the development of the exhibition and be transformed into a ‘Factory Floor’ in homage to introduces key works. William Morris and Andy Warhol’s prolific production techniques. Each week a production method or craft Wednesday 21 January, 1pm skill will be demonstrated by a specialist. Ben Roberts, Curator of Education & Public Programmes at Modern Art Oxford discusses The Factory Floor is a rare opportunity to see creative education, collaboration and participation in relation to processes such as metal casting, dry stone walling, the work of Morris and Warhol. bookbinding, weaving and tapestry. LOVE IS Wednesday 4 February, 1pm These drop-in sessions provide a chance to meet Paul Teigh, Production Manager at Modern Art Oxford makers and craftspeople working with these processes discusses manufacturing and design processes today. Please see website for further details. inherent in the work of Morris and Warhol. TALKS Wednesday 18 February, 1pm Artist talk Ciara Moloney, Curator of Exhibitions & Projects Saturday 6 December, 6pm Free, booking essential at Modern Art Oxford discusses key works in the ENOUGH Jeremy Deller in conversation with Ralph Rugoff, exhibition and their influence on artistic practices Director, Hayward Gallery, London. today. Perspectives: Myth Thursday 15 January, 7pm BASEMENT: PERFORMANCE A series of short talks on myths and myth making from Live in the Studio the roots of medieval tales to our collective capacity December 2014 – February 2015 for fiction and how myths are made in contemporary A short series of performance projects working with culture. -

Pop Comes from the Outside: Warhol and Queer Childhood 78

c... o VI m. m '"...m »~ Z c:== ZI o N o U K E UN I V E R SIT Y PRE S S Durham and London 1996 Second printing, 1996 © 1996 Duke University Press All rights reserved ''I'll Be Your Mirror Stage: Andy Warhol and the Cultural Imaginary," © 1996 David E. James Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 00 Typeset in Berkeley Medium by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii JENNIFER DOYLE, JONATHAN FLATLEY, JOSE ESTEBAN MUNOZ Introduction 1 SIMON WATNEY Queer Andy 20 DAVID E. JAMES I'll Be Your Mirror Stage: Andy Warhol in the Cultural Imaginary 31 THOMAS WAUGH Cock teaser 51 MICHAEL MOON Screen Memories, or, Pop Comes from the Outside: Warhol and Queer Childhood 78 JONATHAN FLATLEY Warhol Gives Good Face: Publicity and the Politics of Prosopopoeia 101 EVE KOSOFSKY SEDGWICK Queer Performativity: Warhol's Shyness/Warhol's Whiteness 134 JOSE ESTEBAN MUNOZ Famous and Dandy Like B. 'n' Andy: Race, Pop, and Basquiat 144 vi Contents BRIAN SELSKY "I Dream of Genius, ,," 180 JENNIFER DOYLE Tricks of the Trade: Pop Art/Pop Sex 191 MARCIE FRANK Popping Off Warhol: From the Gutter to the Underground and Beyond 210 MANDY MERCK Figuring Out Andy Warhol 224 SASHA TORRES The Caped Crusader of Camp: Pop, Camp, and the Batman Television Series 238 Bibliography 257 Contributors 267 Index 269 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS his book was put together with the energy and excitement gener ated by a conference we organized at Duke University in January 1993 called "Re-Reading Warhol: The Politics of Pop." Our first thanks, then, go to the people who were instrumental in making that event happen, and especially to the people who participated in and attended the conference but did not contribute to this collection of essays. -

Factory Girl Free Download

FACTORY GIRL FREE DOWNLOAD Pamela Oldfield | 160 pages | 03 Jan 2011 | Scholastic | 9781407116723 | English | London, United Kingdom Factory Girl (Rolling Stones song) Sign up here. The film is framed by Edie Sedgwick Sienna Miller being interviewed in a hospital several years after her time as an Andy Warhol superstar. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. We want to hear what you have to say but need to verify your account. Certified Fresh Picks. Beggars Banquet. Was this review helpful to you? Waiting Factory Girl a girl who's got curlers in her hair Waiting for Factory Girl girl, she has no money anywhere Factory Girl get buses everywhere, waiting for a factory girl. Micheal Compton. Andy Warhol dove into most things artistic; shaping Pop Art, producing The Velvet Underground, and making his own films. Namespaces Article Talk. In Factory Girl, a jumbled account of the short life and photogenic hard times of the first Andy Warhol superstar, Edie Sedgwick, Sienna Miller makes Sedgwick into an archetypal over-confident blond with a mannered young Kathleen Turner croak. Best Horror Movies. Add Article. Andy Warhol: You're the boss, applesauce! By the end of the film, I didn't think I learned anything true. We want to hear what you have to say but need to verify your email. Log in here. June 15, Clear your history. Sienna Miller defended the film against Dylan's allegations, saying in an interview with the Guardian, Factory Girl blames Warhol more than anyone, because he did abandon her Regal Coming Soon. -

Spring2020.Pdf

B A U M A N R A R E B O O K S Spring 2020 BaumanRareBooks.com 1-800-97-bauman (1-800-972-2862) or 212-751-0011 [email protected] New York 535 Madison Avenue (Between 54th & 55th Streets) New York, NY 10022 800-972-2862 or 212-751-0011 Monday - Saturday: 10am to 6pm Las Vegas Grand Canal Shoppes The Venetian | The Palazzo 3327 Las Vegas Blvd., South, Suite 2856 Las Vegas, NV 89109 888-982-2862 or 702-948-1617 Sunday - Thursday: 10am to 11pm Friday - Saturday: 10am to Midnight Philadelphia (by appointmEnt) 1608 Walnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 215-546-6466 | (fax) 215-546-9064 Monday - Friday: 9am to 5pm all booKS aRE ShippEd on appRoval and aRE fully guaRantEEd. Any items may be returned within ten days for any reason (please notify us before returning). All reimbursements are limited to original purchase price. We accept all major credit cards. Shipping and insurance charges are additional. Packages will be shipped by UPS or Federal Express unless another carrier is requested. Next-day or second-day air service is available upon request. www.baumanrarebooks.com twitter.com/baumanrarebooks facebook.com/baumanrarebooks On the cover: Item no. 4. On this page: Item no. 79. Table of Contents 16 4 42 100 113 75 A Representative Selection 3 English History, Travel & Thought 20 Literature 38 Children’s Literature, Art & Architecture 58 Science, Economics & Natural History 70 Judaica 81 The American xperienceE 86 93 Index 103 A A Representative Selection R e p r e s e n t a t i v e S e l e c t i o n 4 S “Incomparably The Most Important Work In p The English Language”: The Fourth Folio Of r Shakespeare, 1685, An Exceptionally Lovely Copy i 1. -

Storytelling and Survival in the 'Murderer's House'

Storytelling and Survival in the “Murderer’s House”: Gender, Voice(lessness) and Memory in Helma Sanders-Brahms’ Deutschland, bleiche Mutter by Rebecca Reed B.A., University of Victoria, 2003 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies © Rebecca Reed, 2009 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Storytelling and Survival in the “Murderer’s House”: Gender, Voice(lessness) and Memory in Helma Sanders-Brahms’ Deutschland, bleiche Mutter by Rebecca Reed B.A., University of Victoria, 2003 Supervisory Committee Dr. Helga Thorson, Supervisor (Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies) Dr. Charlotte Schallié, Departmental Member (Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies) Dr. Perry Biddiscombe, Outside Member (Department of History) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Helga Thorson, Supervisor (Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies) Dr. Charlotte Schallié, Departmental Member (Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies) Dr. Perry Biddiscombe, Outside Member (Department of History) ABSTRACT Helma Sanders-Brahms’ film Deutschland, bleiche Mutter is an important contribution to (West) German cinema and to the discourse of Vergangenheitsbewältigung or “the struggle to come to terms with the Nazi past” and arguably the first film of New German Cinema to take as its central plot a German woman’s gendered experiences of the Second World War and its aftermath. In her film, Deutschland, bleiche Mutter, Helma Sanders-Brahms uses a variety of narrative and cinematic techniques to give voice to the frequently neglected history of non- Jewish German women’s war and post-war experiences. -

Fltc Dvd / German

Revised 4/1/2013 FLTC German DVD List DVD/GER/1 - TALES FROM EUROPE: LITTLE MOOK 1953 (96 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH DUBBING, FRENCH & SPANISH NARRATION DVD/GER/2 - TALES FROM EUROPE: GOLDEN GOOSE 1964 (64 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH DUBBING, FRENCH & SPANISH NARRATION DVD/GER/3 - TALES FROM EUROPE: SINGING, RINGING TREE 1957 (70 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH DUBBING, FRENCH & SPANISH NARRATION DVD/GER/4 - TALES FROM EUROPE: DEVIL'S 3 GOLDEN HAIRS 1977 (88 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH DUBBING, FRENCH & SPANISH NARRATION DVD/GER/5 - BANDITS Katja von Garnier, 1997 (110 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH SUBTITLES DVD/GER/6 - CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI Robert Wiene, 1920 (72 min.) SILENT w/ ENGLISH SUBTITLES DVD/GER/7 - LOLA Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1981 (120 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH SUBTITLES DVD/GER/8 - MARRIAGE OF MARIA BRAUN Fassbinder, 1979 (120 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH SUBTITLES DVD/GER/9 - VERONIKA VOSS Fassbinder, 1982 (104 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH SUBTITLES Revised 4/1/2013 DVD/GER/10 - WUNDER VON BERN Sonke Wortmann, 2004 (118 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH SUBTITLES DVD/GER/11 - PRINCESS AND THE WARRIOR Tom Tykwer, 2000 (133 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH, FRENCH, SPANISH, & PORTUGESE SUBTITLES DVD/GER/12 - THE OGRE Volker Schlondorff, 1996 (117 min.) ENGLISH DVD/GER/13 - LEGEND OF RITA Volker Schlondorff 2000 (101 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH SUBTITLES DVD/GER/14 - TITANIC Herbert Selpin & Werner Klingler, 1943 (85 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH SUBTITLES DVD/GER/15 - INTO THE ARMS OF STRANGERS Mark Harris, 2000 (122 min.) ENGLISH DVD/GER/16 - IN JULY Faith Akin, 2004 (96 min.) GERMAN w/ ENGLISH SUBTITLES DVD/GER/17 - THE LAST LAUGH F.W.