Storytelling and Survival in the 'Murderer's House'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: August 6th, 2007 I, __________________Julia K. Baker,__________ _____ hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in: German Studies It is entitled: The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life-Writing and Documentary Film This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Katharina Gerstenberger Dr. Sara Friedrichsmeyer Dr. Todd Herzog The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life-Writing and Documentary Film A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) In the Department of German Studies Of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julia K. Baker M.A., Bowling Green State University, 2000 M.A., Karl Franzens University, Graz, Austria, 1998 Committee Chair: Katharina Gerstenberger ABSTRACT “The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life- Writing and Documentary Film” is a study of the literary responses of writers who were Jewish children in hiding and exile during World War II and of documentary films on the topic of refugee children and children in exile. The goal of this dissertation is to investigate the relationships between trauma, memory, fantasy and narrative in a close reading/viewing of different forms of Jewish life-writing and documentary film by means of a scientifically informed approach to childhood trauma. Chapter 1 discusses the reception of Binjamin Wilkomirski’s Fragments (1994), which was hailed as a paradigmatic traumatic narrative written by a child survivor before it was discovered to be a fictional text based on the author’s invented Jewish life-story. -

Barbara Hammer, 70 Years Old, Hands the Camera to Gina Carducci, a Young Queer Film- Maker

Generations is a film about mentoring and passing on the tradi- tion of personal experimental filmmaking. Barbara Hammer, 70 years old, hands the camera to Gina Carducci, a young queer film- maker. Shooting during the last days of Astroland at Coney Is- land, New York, the filmmakers find that the inevitable fact of ageing echoes in the architecture of the amusement park and in the emulsion of the film medium itself. Editing completely sep- arately both picture and sound, the filmmakers join their films in the middle when they’ve finished, making a true generational and experimental experiment. In a time when digital dominates the art domain, a DIY aesthet- ic is embraced by Gina Carducci, a young thirty-year-old filmmak- er who hand processes 16mm film and a seventy-year-old pioneer of queer experimental cinema, Barbara Hammer. Hammer invites Carducci to collaborate on a new film, Generations. Barbara Hammer Celebrating Hammer’s spontaneous shooting style and dense ed- Maya Deren’s Sink iting montage with Carducci’s studied cinematography, the two filmmakers, generations apart in age, shoot the last days of Astro- land in Coney Island, New York. The aged but vibrant amusement Eine Hommage an die Mutter des amerikanischen Avantgarde- park, characteristic of the 70-year-old Hammer, is a fitting envi- films. Der Film beschwört durch Gespräche mit WeggefährtInnen ronment for the photoplay of the two Bolex filmmakers. und ZeitgenossInnen den Geist einer überlebensgroßen Person. Teiji Itos Familie, Carolee Schneemann und Judith Malvina schwe- Inspired by the revolutionary Shirley Clarke film,Bridges Go ben durch Derens Wohnorte und erinnern sich an kleinste Details Round (1953), where Clarke printed the same footage twice us- der architektonischen und persönlichen Innenräume. -

Here Is Endlessness Somewhere Else

Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau White Office 26, rue George Sand, 37000 Tours Vernissage : vendredi 21 mai 2010 Exposition du 22 mai au 13 juin 2010 Titre : Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else (Bas Jan Ader (“here is always somewhere else”) + Samuel Beckett (“lessness” – “sans”)) James Joyce, “Ulysse” : “le froid des espaces interstellaires, des milliers de degrés en-dessous du point de congélation ou du zéro absolu de Fahrenheit, centigrade ou Réaumur : les indices premiers de l’aube proche.” Alphaville – Jean-Luc Godard Alfaville Mel Bochner & TTrioreau (4 affiches perforées sur mur gris – édition multiples : 5 + 2 EA) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (néon blanc sur mur gris – édition multiples : 5 + 2 EA) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (White Office – façade grise + fenêtre écran, format panavision 2/35) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (White Office – intérieur gris + projecteur 35mm, film 35mm vierge gris, format panavision 2/35 + néon blanc sur mur gris) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (White Office – intérieur gris + projecteur 35mm, film 35mm vierge gris, format panavision 2/35 + néon blanc sur mur gris) Annexes : Lessness A Story by SAMUEL BECKETT (1970) Ruins true refuge long last towards which so many false time out of mind. All sides endlessness earth sky as one no sound no stir. Grey face two pale blue little body heart beating only up right. Blacked out fallen open four walls over backwards true refuge issueless. Scattered ruins same grey as the sand ash grey true refuge. Four square all light sheer white blank planes all gone from mind. Never was but grey air timeless no sound figment the passing light. -

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

Female Nazi Perpetrators Kara Mercure Female Nazi Perpetrators

Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 19 Article 13 2015 Female Nazi Perpetrators Kara Mercure Female Nazi Perpetrators Follow this and additional works at: https://openspaces.unk.edu/undergraduate-research-journal Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Gender Commons Recommended Citation Mercure, Kara (2015) "Female Nazi Perpetrators," Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 19 , Article 13. Available at: https://openspaces.unk.edu/undergraduate-research-journal/vol19/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of Undergraduate Research & Creative Activity at OpenSPACES@UNK: Scholarship, Preservation, and Creative Endeavors. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized editor of OpenSPACES@UNK: Scholarship, Preservation, and Creative Endeavors. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Female Nazi Perpetrators Kara Mercure Nazi women perpetrators have evolved in literary works as they have become more known to scholars in the last 15 years. However, public knowledge of women’s involvement in the regime is seemingly unfamiliar. Curiosity in the topic of women’s motivation as perpetrators of genocide and war crimes has developed in contrast to a stereotypical perception of women’s gender roles to be more domesticated. Much literature has been devoted to explaining Nazi ideology and how women fit into the system. Claudia Koonz’s, Mother’s in the Fatherland, demonstrates the involvement of women in support of National Socialism. The book focuses on women in support of the regime and how they supported the regime through domestic means. Robert G. Moeller’s, The Nazi State and German Society, also examines how women were drawn to National Socialism and how their ideals progressed through the regime. -

Beckett and Nothing with the Negative Spaces of Beckett’S Theatre

8 Beckett, Feldman, Salcedo . Neither Derval Tubridy Writing to Thomas MacGreevy in 1936, Beckett describes his novel Murphy in terms of negation and estrangement: I suddenly see that Murphy is break down [sic] between his ubi nihil vales ibi nihil velis (positive) & Malraux’s Il est diffi cile à celui qui vit hors du monde de ne pas rechercher les siens (negation).1 Positioning his writing between the seventeenth-century occasion- alist philosophy of Arnold Geulincx, and the twentieth-century existential writing of André Malraux, Beckett gives us two visions of nothing from which to proceed. The fi rst, from Geulincx’s Ethica (1675), argues that ‘where you are worth nothing, may you also wish for nothing’,2 proposing an approach to life that balances value and desire in an ethics of negation based on what Anthony Uhlmann aptly describes as the cogito nescio.3 The second, from Malraux’s novel La Condition humaine (1933), contends that ‘it is diffi cult for one who lives isolated from the everyday world not to seek others like himself’.4 This chapter situates its enquiry between these poles of nega- tion, exploring the interstices between both by way of neither. Drawing together prose, music and sculpture, I investigate the role of nothing through three works called neither and Neither: Beckett’s short text (1976), Morton Feldman’s opera (1977), and Doris Salcedo’s sculptural installation (2004).5 The Columbian artist Doris Salcedo’s work explores the politics of absence, par- ticularly in works such as Unland: Irreversible Witness (1995–98), which acts as a sculptural witness to the disappeared victims of war. -

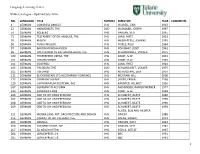

1 Language Learning Center Video Catalogue

Language Learning Center Video Catalogue – Updated July 2016 NO. LANGUAGE TITLE FORMAT DIRECTOR YEAR COMMENTS 4 GERMAN CONGRESS DANCES VHS CHARELL, ERIK 1932 22 GERMAN HARMONISTS, THE DVD VILSMAIER, JOSEPH 1997 54 GERMAN KOLBERG VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1945 71 GERMAN TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE, THE VHS LANG, FRITZ 1933 95 GERMAN MALOU VHS MEERAPFELE, JEANINE 1983 96 GERMAN TONIO KROGER VHS THIELE, ROLF 1964 97 GERMAN BARON MUNCHHAUSEN VHS VON BAKY, JOSEF 1943 99 GERMAN LOST HONOR OF KATHARINA BLUM, THE VHS SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 100 GERMAN THREEPENNY OPERA, THE VHS PABST, G.W. 1931 101 GERMAN JOYLESS STREET VHS PABST, G.W. 1925 102 GERMAN SIEGFRIED VHS LANG, FRITZ 1924 103 GERMAN TIN DRUM, THE DVD SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 105 GERMAN TIEFLAND VHS RIEFENSTAHL, LENI 1954 111 GERMAN BLICKKONTAKE (TO ACCOMPANY KONTAKE) VHS MCGRAW HILL 2000 127 GERMAN GERMANY AWAKE VHS LEISER, ERWIN 1968 129 GERMAN CAPTAIN FROM KOEPENIK, THE VHS KAUNTER, HELMUT 1956 167 GERMAN GERMANY IN AUTUMN VHS FASSBINDER, RANIER WERNER 1977 199 GERMAN PANDORA'S BOX VHS PABST, G.W. 1928 206 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 207 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 208 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 209 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 ROSEN, BOB AND ANDREA 211 GERMAN VIENNA 1900: ART, ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN VHS SIMON 1986 253 GERMAN CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, THE VHS WIENE, ROBERT 1919 265 GERMAN DAMALS VHS HANSEN, ROLF 1943 266 GERMAN GOLDENE STADT, DIE VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1942 267 GERMAN ZU NEUEN -

Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination EDITED BY TARA FORREST Amsterdam University Press Alexander Kluge Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination Edited by Tara Forrest Front cover illustration: Alexander Kluge. Photo: Regina Schmeken Back cover illustration: Artists under the Big Top: Perplexed () Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn (paperback) isbn (hardcover) e-isbn nur © T. Forrest / Amsterdam University Press, All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustra- tions reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Alexander Kluge …and in memory of Miriam Hansen Table of Contents Introduction Editor’s Introduction Tara Forrest The Stubborn Persistence of Alexander Kluge Thomas Elsaesser Film, Politics and the Public Sphere On Film and the Public Sphere Alexander Kluge Cooperative Auteur Cinema and Oppositional Public Sphere: Alexander Kluge’s Contribution to G I A Miriam Hansen ‘What is Different is Good’: Women and Femininity in the Films of Alexander Kluge Heide -

Bücher Für Die Front

Bücher für die Front Feldpostreihen des Zweiten Weltkriegs Ausstellungskatalog Herausgegeben von Thorsten Unger Wehrhahn Verlag Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Natio- nalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. 1. Auflage 2019 Wehrhahn Verlag www.wehrhahn-verlag.de Satz in Indesign: Cosima Oomen-Müller, Magdeburg Umschlaggestaltung: Wehrhahn Verlag Umschlagabbildung: Feldpostausgabe aus dem Bestand der Ute-und-Wolfram-Neumann-Stiftung (UB Magdeburg: STN 681, G. Neesse), Foto: Unger Druck und Bindung: Sowa, Piaseczno Alle Rechte vorbehalten Printed in Europe © by Wehrhahn Verlag, Hannover ISBN 978–3–86525–731–4 Inhalt Thorsten Unger Buchreihen des Zweiten Weltkriegs. Eine Einleitung ........................................... 9 Einführende Informationen Annekatrin Bartelmann Publizieren in der Nazi-Zeit ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 39 Sharline-Kathrin Dünow Das Verbot gotischer Schriften ��������������������������������������������������������������������������� 45 Diana Richter Heldenliteratur? ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 52 Kim Ludwig »Geistige Futterkisten« �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 58 Katalog 1. (Feldpost) Reihen eingeführter Verlagshäuser ............................................ 69 1.1 -

Course Outline

Prof. Fatima Naqvi German 01:470:360:01; cross-listed with 01:175:377:01 (Core approval only for 470:360:01!) Fall 2018 Tu 2nd + 3rd Period (9:50-12:30), Scott Hall 114 [email protected] Office hour: Tu 1:10-2:30, New Academic Building or by appointment, Rm. 4130 (4th Floor) Classics of German Cinema: From Haunted Screen to Hyperreality Description: This course introduces students to canonical films of the Weimar, Nazi, post-war and post-wall period. In exploring issues of class, gender, nation, and conflict by means of close analysis, the course seeks to sensitize students to the cultural context of these films and the changing socio-political and historical climates in which they arose. Special attention will be paid to the issue of film style. We will also reflect on what constitutes the “canon” when discussing films, especially those of recent vintage. Directors include Robert Wiene, F.W. Murnau, Fritz Lang, Lotte Reiniger, Leni Riefenstahl, Alexander Kluge, Volker Schlöndorff, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Andreas Dresen, Christian Petzold, Jessica Hausner, Michael Haneke, Angela Schanelec, Barbara Albert. The films are available at the Douglass Media Center for viewing. Taught in English. Required Texts: Anton Kaes, M ISBN-13: 978-0851703701 Recommended Texts (on reserve at Alexander Library): Timothy Corrigan, A Short Guide to Writing about Film Rob Burns (ed.), German Cultural Studies Lotte Eisner, The Haunted Screen Sigmund Freud, Writings on Art and Literature Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler Anton Kaes, Shell Shock Cinema: Weimar Cinema and the Wounds of War Noah Isenberg, Weimar Cinema Gerd Gemünden, Continental Strangers Gerd Gemünden, A Foreign Affair: Billy Wilder’s American Films Sabine Hake, German National Cinema Béla Balász, Early Film Theory Siegfried Kracauer, The Mass Ornament Brad Prager, The Cinema of Werner Herzog Eric Ames, Ferocious Reality: Documentary according to Werner Herzog Eric Ames, Werner Herzog: Interviews N. -

Strange Contracts: Elfriede Jelinek and Michael Haneke VICKY LEBEAU

Strange Contracts: Elfriede Jelinek and Michael Haneke VICKY LEBEAU Abstract: This essay explores the representation of sexuality and vision in Elfriede Jelinek’s Die Klavierspielerin [The Piano Teacher] (1983) and Michael Haneke’s La Pianiste (2001). In its focus on the relation between Mother and Erika, Die Klavierspielerin brings right to the fore the grounding of both sexuality and visuality in the ongoing ties between mother and child. Displac- ing that novel onto the screen, Haneke redoubles its focus on vision. It is in the convergence between the two that we can begin to explore what may be described as the maternal dimension of the various technologies of vision that have come to pervade the everyday experience of looking—their effect on our ways of understanding the relations between visuality and selfhood, visuality and mind. Keywords: feminism, Michael Haneke, Elfriede Jelinek, The Piano Teacher, pornography, psychoanalysis, psychoanalytic film theory, sadomasochism, The Seventh Continent, sexuality, spectatorship, vision, visual culture, voyeur- ism, D. W. Winnicott Why would a woman welcome her own murder? Not her own death, simply, not even her suicide, but her murder, the loss of her life at the hands of another? To read Elfriede Jelinek’s Die Klavierspielerin [The Piano Teacher], first published in 1983, is to be caught up in that question, its wayward implication in a woman’s pursuit of pleasure, of a “life of her own,” which for much of the book, appears to be possible only in, and through, her eyes. “All Erika wants to do is watch”; “[S] he simply wants to sit there and look. -

Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft Und Psychologie Der Freien Universität Berlin

Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie der Freien Universität Berlin * Physiological correlates and neural circuitry of being moved Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt von Wassiliwizky, Eugen Diplompsychologe Berlin, 2017 Erstgutachter Professor Dr. Stefan Kölsch Zweitgutachter Professor Dr. Thomas Jacobsen Tag der Disputation: 10.11.2017 Gemeinsame Promotionsordnung zum Dr. phil./Ph.D. der Freien Universität Berlin vom 2. Dezember 2008 (FU-Mitteilungen 60/2008) ii Anicca vata sankhara Uppada vaya dhammino Uppajhitva nirujjhanti Tesam vupasamo sukho. — Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha) iii Abstract The present dissertation examines the psychophysiological and neural correlates of being emotionally moved in context of aesthetic experiences. Emotional chills and emotional tears are identified, and experimentally drawn upon, as physiological markers of particularly intense episodes of being moved. In a first step, the connection between emotional chills and being moved is established by means of a film clip rating study. The second study focuses on poetic language. In a series of four experiments that use physiological, behavioral, and fMRI neuroimaging data, poetry is shown to be capable of inducing profound emotional engagement as characterized by subjectively reported chills and objectively recorded piloerection (i.e., goosebumps captured by the goosecam). Moreover, although chills represent highly rewarding experiences for which both previous neuroimaging data on music and the present fMRI results on poetry show activations in the mesolimbic reward circuitry, acquisition of facial electromyographic activity reveals strong effects for the facial indicators of negative affect. This co- activation of negative affect and (aesthetic) pleasure represents a key characteristic of the mixed emotional state of being moved.