James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“I Am Not Your Negro” (2016) Argument-Based Questions

“I Am Not Your Negro” (2016) Argument-Based Questions These argument-based questions accompany the 2016 documentary “I Am Not Your Negro,” which was created from a set of unpublished writings by James Baldwin. Baldwin was working on a book, one that he did not complete but for which he prepared extensive notes, taking a very autobiographical look at the divergent and convergent lives and deaths of three towing civil rights leaders: Martin Luther King, Jr., Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X. The documentary and these questions can be used as part of a unit on Civil Rights, African-American history, or simply American history. Students can be given these questions in advance of screening the film, for completion afterward. Or, the documentary can be paused at intervals so students can discuss or respond in writing to the questions. The timings attached to each question are approximately (not precisely) aligned with the film. It would be sufficient to screen the first half of this documentary – through the first 45 minutes – for classes with younger students, students sensitive to images of violence (there are several of these in the film’s second half), or students very unfamiliar with the history of the Civil Rights movement. There are various arguable angles into the civil rights era, and this documentary, as the questions below suggest. One overarching debatable issue is: James Baldwin establishes as one of his unifying arguments, in the writings on which “I Am Not Your Negro” is based and elsewhere, that America as a whole has been more damaged by racism than have African-Americans and other racial minorities, racism’s direct targets. -

Here Is Endlessness Somewhere Else

Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau White Office 26, rue George Sand, 37000 Tours Vernissage : vendredi 21 mai 2010 Exposition du 22 mai au 13 juin 2010 Titre : Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else (Bas Jan Ader (“here is always somewhere else”) + Samuel Beckett (“lessness” – “sans”)) James Joyce, “Ulysse” : “le froid des espaces interstellaires, des milliers de degrés en-dessous du point de congélation ou du zéro absolu de Fahrenheit, centigrade ou Réaumur : les indices premiers de l’aube proche.” Alphaville – Jean-Luc Godard Alfaville Mel Bochner & TTrioreau (4 affiches perforées sur mur gris – édition multiples : 5 + 2 EA) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (néon blanc sur mur gris – édition multiples : 5 + 2 EA) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (White Office – façade grise + fenêtre écran, format panavision 2/35) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (White Office – intérieur gris + projecteur 35mm, film 35mm vierge gris, format panavision 2/35 + néon blanc sur mur gris) Here is Endlessness Somewhere Else TTrioreau (White Office – intérieur gris + projecteur 35mm, film 35mm vierge gris, format panavision 2/35 + néon blanc sur mur gris) Annexes : Lessness A Story by SAMUEL BECKETT (1970) Ruins true refuge long last towards which so many false time out of mind. All sides endlessness earth sky as one no sound no stir. Grey face two pale blue little body heart beating only up right. Blacked out fallen open four walls over backwards true refuge issueless. Scattered ruins same grey as the sand ash grey true refuge. Four square all light sheer white blank planes all gone from mind. Never was but grey air timeless no sound figment the passing light. -

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

Beckett and Nothing with the Negative Spaces of Beckett’S Theatre

8 Beckett, Feldman, Salcedo . Neither Derval Tubridy Writing to Thomas MacGreevy in 1936, Beckett describes his novel Murphy in terms of negation and estrangement: I suddenly see that Murphy is break down [sic] between his ubi nihil vales ibi nihil velis (positive) & Malraux’s Il est diffi cile à celui qui vit hors du monde de ne pas rechercher les siens (negation).1 Positioning his writing between the seventeenth-century occasion- alist philosophy of Arnold Geulincx, and the twentieth-century existential writing of André Malraux, Beckett gives us two visions of nothing from which to proceed. The fi rst, from Geulincx’s Ethica (1675), argues that ‘where you are worth nothing, may you also wish for nothing’,2 proposing an approach to life that balances value and desire in an ethics of negation based on what Anthony Uhlmann aptly describes as the cogito nescio.3 The second, from Malraux’s novel La Condition humaine (1933), contends that ‘it is diffi cult for one who lives isolated from the everyday world not to seek others like himself’.4 This chapter situates its enquiry between these poles of nega- tion, exploring the interstices between both by way of neither. Drawing together prose, music and sculpture, I investigate the role of nothing through three works called neither and Neither: Beckett’s short text (1976), Morton Feldman’s opera (1977), and Doris Salcedo’s sculptural installation (2004).5 The Columbian artist Doris Salcedo’s work explores the politics of absence, par- ticularly in works such as Unland: Irreversible Witness (1995–98), which acts as a sculptural witness to the disappeared victims of war. -

How Bigger Was Born Anew

Fall 2020 29 ow Bier as Born new datation Reuration and Double Consciousness in Nambi E elle’s Native Son Isaiah Matthew Wooden This essay analyzes Nambi E. Kelley’s stage adaptation of Native Son to consider the ways tt Aicn Aeicn is itlie by n constitte to cts o etion t sharpens particular focus on how Kelley reinvigorates Wright’s novel’s searing social and cil cities by ctiely ein te oisin etpo o oble consciosness n iin ne o, enin, n se to te etpo, elleys Native Son extends the debates about “the problem of the color line” that Du Bois’s writing helped engender at te beinnin o te tentiet centy into te tentyst n, in so oin, opens citicl space to reckon with the persistent and pernicious problem of anti-Black racism. ewords adaptation, refguration, double consciousness, Native Son, Nambi E. Kelley This essay takes as a central point of departure the claim that African American drama is vitalized by and, indeed, constituted through acts of refguration. It is such acts that endow the remarkably capacious genre with any sense or semblance of coherence. Retion is notably a word with multiple signifcations. It calls to mind processes of representation and recalculation. It also points to matters of meaning-making and modifcation. The pref re does important work here, suggesting change, alteration, or even improvement. For the purposes of this essay, I use etion to refer to the strategies, practices, methods, and techniques that African American dramatists deploy to transform or give new meaning to certain ideas, concepts, artifacts, and histories, thereby opening up fresh interpretive and defnitional possibilities and, when appropriate, prompting much-needed reckonings. -

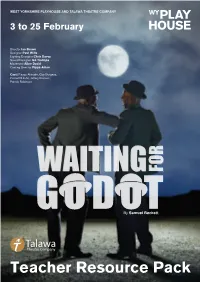

Waiting for Godot’

WEST YORKSHIRE PLAYHOUSE AND TALAWA THEATRE COMPANY 3 to 25 February Director Ian Brown Designer Paul Wills Lighting Designer Chris Davey Sound Designer Ian Trollope Movement Aline David Casting Director Pippa Ailion Cast: Fisayo Akinade, Guy Burgess, Cornell S John, Jeffery Kissoon, Patrick Robinson By Samuel Beckett Teacher Resource Pack Introduction Hello and welcome to the West Yorkshire Playhouse and Talawa Theatre Company’s Educational Resource Pack for their joint Production of ‘Waiting for Godot’. ‘Waiting for Godot’ is a funny and poetic masterpiece, described as one of the most significant English language plays of the 20th century. The play gently and intelligently speaks about hardship, friendship and what it is to be human and in this unique Production we see for the first time in the UK, a Production that features an all Black cast. We do hope you enjoy the contents of this Educational Resource Pack and that you discover lots of interesting and new information you can pass on to your students and indeed other Colleagues. Contents: Information about WYP and Talawa Theatre Company Cast and Crew List Samuel Beckett—Life and Works Theatre of the Absurd Characters in Waiting for Godot Waiting for Godot—What happens? Main Themes Extra Activities Why Godot? why now? Why us? Pat Cumper explains why a co-production of an all-Black ‘Waiting for Godot’ is right for Talawa and WYP at this time. Interview with Ian Brown, Director of Waiting for Godot In the Rehearsal Room with Assistant Director, Emily Kempson Rehearsal Blogs with Pat Cumper and Fisayo Akinade More ideas for the classroom to explore ‘Waiting For Godot’ West Yorkshire Playhouse / Waiting for Godot / Resource Pack Page 1 Company Information West Yorkshire Playhouse Since opening in March 1990, West Yorkshire Playhouse has established a reputation both nationally and internationally as one of Britain’s most exciting producing theatres, winning awards for everything from its productions to its customer service. -

Song Pack Listing

TRACK LISTING BY TITLE Packs 1-86 Kwizoke Karaoke listings available - tel: 01204 387410 - Title Artist Number "F" You` Lily Allen 66260 'S Wonderful Diana Krall 65083 0 Interest` Jason Mraz 13920 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliot. 63899 1000 Miles From Nowhere` Dwight Yoakam 65663 1234 Plain White T's 66239 15 Step Radiohead 65473 18 Til I Die` Bryan Adams 64013 19 Something` Mark Willis 14327 1973` James Blunt 65436 1985` Bowling For Soup 14226 20 Flight Rock Various Artists 66108 21 Guns Green Day 66148 2468 Motorway Tom Robinson 65710 25 Minutes` Michael Learns To Rock 66643 4 In The Morning` Gwen Stefani 65429 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 66292 4Ever` The Veronicas 64132 5 Colours In Her Hair` Mcfly 13868 505 Arctic Monkeys 65336 7 Things` Miley Cirus [Hannah Montana] 65965 96 Quite Bitter Beings` Cky [Camp Kill Yourself] 13724 A Beautiful Lie` 30 Seconds To Mars 65535 A Bell Will Ring Oasis 64043 A Better Place To Be` Harry Chapin 12417 A Big Hunk O' Love Elvis Presley 2551 A Boy From Nowhere` Tom Jones 12737 A Boy Named Sue Johnny Cash 4633 A Certain Smile Johnny Mathis 6401 A Daisy A Day Judd Strunk 65794 A Day In The Life Beatles 1882 A Design For Life` Manic Street Preachers 4493 A Different Beat` Boyzone 4867 A Different Corner George Michael 2326 A Drop In The Ocean Ron Pope 65655 A Fairytale Of New York` Pogues & Kirsty Mccoll 5860 A Favor House Coheed And Cambria 64258 A Foggy Day In London Town Michael Buble 63921 A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley 1053 A Gentleman's Excuse Me Fish 2838 A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins 2349 A Girl Like -

Dystopian America in Revolutionary Road and 'Sonny's Blues'

Dystopian America in Revolutionary Road and ‘Sonny’s Blues’ Kate Garrow America as a nation is often associated with values of freedom, nationalism, and the optimistic pursuit of dreams. However, in Revolutionary Road1 by Richard Yates and ‘Sonny’s Blues’2 by James Baldwin, the authors display a pessimistic view of America as a land characterised by suffering and entrapment, supporting the view of literary critic Leslie Fiedler that American literature is one ‘of darkness and the grotesque’.3 Through the contrasting communities of white middle-class suburbia and Harlem, the authors depict a dystopian America, where characters are stripped of their agency and forced to rely on illusions, false appearances, or escape in order to survive. Both ‘Sonny’s Blues’ and Revolutionary Road confirm that despite America’s appearance as ‘a land of light and affirmation’,4 it hides a much darker reality. Both Yates and Baldwin use characteristics of dystopian literature to create their respective American societies. Revolutionary Road is set in a white middle-class suburban society fuelled by materialism and false appearances. In particular, the community demands conformity. Men must succumb to a bland office job that ‘would swallow them up’5 and 1 R. Yates, Revolutionary Road, London, Random House, 2007. 2 A. Baldwin, ‘Sonny’s Blues’, in Going to Meet the Man, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2013. 3 L. Fiedler, Love and Death in the American Novel, Stein and Day, 1960, p. 29. 4 Fiedler, p. 29. 5 Yates, Revolutionary Road, p. 119. Burgmann Journal VI (2017) women must accept the feminine role as submissive housewife. -

I Am Not Your Negro

Magnolia Pictures and Amazon Studios Velvet Film, Inc., Velvet Film, Artémis Productions, Close Up Films In coproduction with ARTE France, Independent Television Service (ITVS) with funding provided by Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), RTS Radio Télévision Suisse, RTBF (Télévision belge), Shelter Prod With the support of Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, MEDIA Programme of the European Union, Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program, National Black Programming Consortium (NBPC), Cinereach, PROCIREP – Société des Producteurs, ANGOA, Taxshelter.be, ING, Tax Shelter Incentive of the Federal Government of Belgium, Cinéforom, Loterie Romande Presents I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO A film by Raoul Peck From the writings of James Baldwin Cast: Samuel L. Jackson 93 minutes Winner Best Documentary – Los Angeles Film Critics Association Winner Best Writing - IDA Creative Recognition Award Four Festival Audience Awards – Toronto, Hamptons, Philadelphia, Chicago Two IDA Documentary Awards Nominations – Including Best Feature Five Cinema Eye Honors Award Nominations – Including Outstanding Achievement in Nonfiction Feature Filmmaking and Direction Best Documentary Nomination – Film Independent Spirit Awards Best Documentary Nomination – Gotham Awards Distributor Contact: Press Contact NY/Nat’l: Press Contact LA/Nat’l: Arianne Ayers Ryan Werner Rene Ridinger George Nicholis Emilie Spiegel Shelby Kimlick Magnolia Pictures Cinetic Media MPRM Communications (212) 924-6701 phone [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com SYNOPSIS In 1979, James Baldwin wrote a letter to his literary agent describing his next project, Remember This House. -

Gospel Music and the Sonic Fictions of Black Womanhood in Twentieth-Century African American Literature

“UP ABOVE MY HEAD”: GOSPEL MUSIC AND THE SONIC FICTIONS OF BLACK WOMANHOOD IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE Kimberly Gibbs Burnett A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the degree requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature in the Graduate School. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Danielle Christmas Florence Dore GerShun Avilez Glenn Hinson Candace Epps-Robertson ©2020 Kimberly Gibbs Burnett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kimberly Burnett: “Up Above My Head”: Gospel Music and the Sonic Fictions of Black Womanhood in TWentieth-Century African American Literature (Under the direction of Dr. Danielle Christmas) DraWing from DuBois’s Souls of Black Folk (1903), which highlighted the Negro spirituals as a means of documenting the existence of a soul for an African American community culturally reduced to their bodily functions, gospel music figures as a reminder of the narrative of black women’s struggle for humanity and of the literary markers of a black feminist ontology. As the attention to gospel music in texts about black women demonstrates, the material conditions of poverty and oppression did not exclude the existence of their spiritual value—of their claim to humanity that was not based on conduct or social decorum. At root, this project seeks to further the scholarship in sound and black feminist studies— applying concepts, such as saturation, break, and technology to the interpretation of black womanhood in the vernacular and cultural recordings of gospel in literature. Further, this dissertation seeks to offer neW historiography of black female development in tWentieth century literature—one which is shaped by a sounding culture that took place in choir stands, on radios in cramped kitchens, and on stages all across the nation. -

The Short Story: a Non-Definition the Short Story: a Non-Definition

THE SHORT STORY: A NON-DEFINITION THE SHORT STORY: A NON-DEFINITION By MAIRI ELIZABETH FULCHER, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University 1983 -- ---- .----- ----- MASTER OF ARTS (1983) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Short Story: A Non-Definition AUTHOR: Mairi Elizabeth Fulcher, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor L. Hutcheon NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 127 ii ABSTRACT The short story is defined, in this thesis, in terms of what it does rather than what it is. The need to transcend the limitations of brevity determines that the primary qua lity of the form is the necessity of generating a superior quality of response in the reader. Identifying this primary quality allows the critic a focus which enables him to examine the genre in terms of textual strategies specifically designed to generate reader response. This critical pers pective is open-ended and non-deterministic, and thus frees short fiction criticism from its previously prescriptive and proscriptive tendencies, which is why the definition offered here is better termed a "non-definition". iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to Professor Linda Hutcheon for the encouragement, the judicious freedom, and the rig orous criticism involved in her supervision of this thesis. Such appreciation is especially warranted in view of the fact that she graciously agreed to take over the supervision of a work in progress. Thanks is also due to Professor Graham Petrie, my original supervisor, who suggested the change of supervision, and who generously agreed to remain on my committee as a reader.