The Short Story: a Non-Definition the Short Story: a Non-Definition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

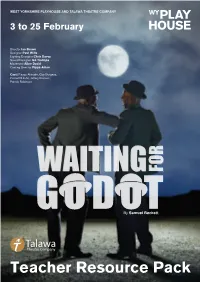

Waiting for Godot’

WEST YORKSHIRE PLAYHOUSE AND TALAWA THEATRE COMPANY 3 to 25 February Director Ian Brown Designer Paul Wills Lighting Designer Chris Davey Sound Designer Ian Trollope Movement Aline David Casting Director Pippa Ailion Cast: Fisayo Akinade, Guy Burgess, Cornell S John, Jeffery Kissoon, Patrick Robinson By Samuel Beckett Teacher Resource Pack Introduction Hello and welcome to the West Yorkshire Playhouse and Talawa Theatre Company’s Educational Resource Pack for their joint Production of ‘Waiting for Godot’. ‘Waiting for Godot’ is a funny and poetic masterpiece, described as one of the most significant English language plays of the 20th century. The play gently and intelligently speaks about hardship, friendship and what it is to be human and in this unique Production we see for the first time in the UK, a Production that features an all Black cast. We do hope you enjoy the contents of this Educational Resource Pack and that you discover lots of interesting and new information you can pass on to your students and indeed other Colleagues. Contents: Information about WYP and Talawa Theatre Company Cast and Crew List Samuel Beckett—Life and Works Theatre of the Absurd Characters in Waiting for Godot Waiting for Godot—What happens? Main Themes Extra Activities Why Godot? why now? Why us? Pat Cumper explains why a co-production of an all-Black ‘Waiting for Godot’ is right for Talawa and WYP at this time. Interview with Ian Brown, Director of Waiting for Godot In the Rehearsal Room with Assistant Director, Emily Kempson Rehearsal Blogs with Pat Cumper and Fisayo Akinade More ideas for the classroom to explore ‘Waiting For Godot’ West Yorkshire Playhouse / Waiting for Godot / Resource Pack Page 1 Company Information West Yorkshire Playhouse Since opening in March 1990, West Yorkshire Playhouse has established a reputation both nationally and internationally as one of Britain’s most exciting producing theatres, winning awards for everything from its productions to its customer service. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

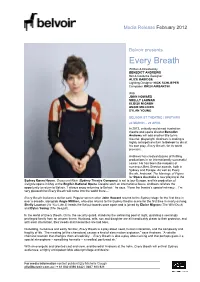

Every Breath Written & Directed by BENEDICT ANDREWS Set & Costume Designer ALICE BABIDGE Lighting Designer NICK SCHLIEPER Composer OREN AMBARCHI

Media Release February 2012 Belvoir presents Every Breath Written & Directed by BENEDICT ANDREWS Set & Costume Designer ALICE BABIDGE Lighting Designer NICK SCHLIEPER Composer OREN AMBARCHI With JOHN HOWARD SHELLY LAUMAN ELOISE MIGNON ANGIE MILLIKEN DYLAN YOUNG BELVOIR ST THEATRE | UPSTAIRS 24 MARCH – 29 APRIL In 2012, critically acclaimed Australian theatre and opera director Benedict Andrews will add another title to his résumé: playwright. Andrews is making a highly anticipated return to Belvoir to direct his own play, Every Breath, for its world premiere. Andrews has created dozens of thrilling productions in an internationally successful career. He has been the recipient of numerous Best Director awards, both in Sydney and Europe. As well as Every Breath, Andrews‟ The Marriage of Figaro for Opera Australia is now playing at the Sydney Opera House, Gross und Klein (Sydney Theatre Company) is set to tour Europe, and his production of Caligula opens in May at the English National Opera. Despite such an international focus, Andrews relishes the opportunity to return to Belvoir. „I always enjoy returning to Belvoir,‟ he says. „I love the theatre‟s special intimacy… I‟m very pleased that Every Breath will come into the world there…‟ Every Breath features a stellar cast. Popular screen actor John Howard returns to the Sydney stage for the first time in over a decade, alongside Angie Milliken, who also returns to the Sydney theatre scene for the first time in nearly as long. Shelly Lauman (As You Like It) treads the Belvoir boards once again and is joined by Eloise Mignon (The Wild Duck) and Dylan Young (The Seagull). -

Collected Shorter Plays of Samuel Beckett Murphy

Collected Shorter Plays Works by Samuel Beckett published by Grove Press Cas cando Mercier and Camier Collected Poems in Molloy English and French More Pricks Than Kicks The Collected Shorter Plays of Samuel Beckett Murphy Company Nohow On (Company, Seen Disjecta Said, Worstward Ho) Endgame Ill Ohio Impromptu Ends and Odds Ill Proust First Love and Other Stories Rockaby Happy Days Stories and Texts How It Is for Nothing I Can't Go On, I'll Go On Three Novels Krapp Last Tape Waiting for Godot The Lost Ones Watt s Malone Dies Worstward Ho Happy Days: Samuel Beckett's Production Notebooks, edited by James Knowlson Samuel Beckett: The Complete Short Prose, 1929-/989, edited and with an introduction and notes by S. E. Gontarski The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beckett: Endgame, edited by S. E. Gontarski The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beckett: Krapp's Last Tape, edited by James Knowlson The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beckett: Waiting for Godot, edited by Dougald McMillan and James Knowlson COLLECTED SHORTER PLAYS SAMUEL BECKETT Grove Press New York Copyright© 1984 by Samuel Beckett All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying,recording, or otherwise,without prior written permission of the publisher. Grove Press 841 Broadway New York, NY 10003 All That Fall © Samuel Beckett, 1957; Act Without Words I © Samuel Beckett, 1959; Act Without Words II© Samuel Beckett,1959; Krapp's Last 'Ihpe© Samuel Beckett,1958; Rough for Theatre I © Samuel Beckett, 1976; Rough for Theatre II© Samuel Beckett,1976; Embers © Samuel Beckett,1959; Rough for Radio I© Samuel Beckett,1976; Rough forRadio II© Samuel Beckett, 1976; Words and Music © Samuel Beckett,1962; Cascando© Samuel Beckett, 1963; Play © Samuel Beckett, 1963; Film © Samuel Beckett, 1967; The Old Tune, adapt. -

The Beckett Collection Ruby Cohn Correspondence 1959-1989

The Beckett Collection Ruby Cohn correspondence 1959-1989 Summary description Held at: Beckett International Foundation, University of Reading Title: The Correspondence of Ruby Cohn Dates of creation: 1959 – 1989 Reference: Beckett Collection--Correspondence/COH Extent: 205 letters and postcards from Samuel Beckett to Ruby Cohn 1 telex message from Beckett to Cohn 1 telegram from Beckett to Cohn 1 postcard addressed to Georges Cravenne 5 letters from Cohn to Beckett (which include Beckett’s responses) 1 envelope containing a typescript of third section of Stirrings Still 2 empty envelopes addressed to Cohn Language of material English unless otherwise stated Administrative information Immediate source of acquisition The correspondence was donated to the Beckett International Foundation by Ruby Cohn in 2002. Copyright/Reproduction Permission to quote from, or reproduce, material from this correspondence collection is required from the Samuel Beckett Estate before publication. Preferred Citation Preferred citation: Correspondence of Samuel Beckett and Ruby Cohn, Beckett International Foundation, Reading University Library (RUL MS 5100) Access conditions Photocopies of the original materials are available for use in the Reading Room. Access to the original letters is restricted. Historical Note 1922, 13 Aug. Born Ruby Burman in Columbus, Ohio 1942 Awarded a BA degree from Hunter College of the City of New York 1946 Married Melvin Cohn (they divorced in 1961) 1952 Awarded a doctorate from the University of Paris 1960 Awarded a second doctorate from Washington University (Saint Louis, Mo.) 1961-1968 Professor of English and Comparative Literature at San Francisco State University 1969-1971 Fellow at the California Institute of the Arts 1972-1992 Professor of Comparative Drama at the University of California, Davis 1992-Present Professor Emerita of Comparative Drama at the University of California, Davis Ruby Cohn (née Burman) was born on 13 August 1922 in Columbus, Ohio, where her father, Peter Burman, was a veterinary student. -

The Censor's “Filthy Synecdoche”: Samuel Beckett and Censorship

Sanglap 2.2 (Feb 2016) Censorship and Literature The Censor’s “filthy synecdoche”: Samuel Beckett and Censorship Martin Schauss “The Royal Court Theatre, London (George Devine) want to do [Endgame] in the Fall. I don’t see how they can do it without cuts which I won’t have.” -- letter to Barney Rosset, 11 Jan 1957 “In London the Lord Chamberpot demands inter alia the removal of the entire prayer scene! I’ve told him to buckingham off.” (sic) -- letter to Alan Schneider, 29 Dec 1957 Samuel Beckett’s antipathy and intolerance towards any form of state censorship are well documented, not least in James Knowlson’s biography Damned to Fame (1996), as are his own run-ins with censorial bodies—the Irish Censorship of Publications Board and, in the United Kingdom, the Lord Chamberlain’s office, which licensed theatre performances in England until 1968. Beckett’s early collection of short stories, More Pricks Than Kicks (MPTK), as well as the novels Murphy, Watt, and Molloy, all ended up banned in Ireland under the Censorship of Publications Act of 1929, sometimes with considerable delay (as in the case of Murphy, banned more than 25 years after being first published), sometimes shortly after publication (as with MPTK and Molloy). The London performances of Waiting for Godot, Endgame, and, to a lesser extent, Krapp’s Last Tape all followed lengthy wrangles with the Lord Chamberlain marked by petty revisions to the text, principle-based compromise, and the writer’s incredulity. 1 This essay argues that Beckett uses obscene material to stage a confrontation with censorship practices in an attempt to turn the tables on the censor and expose the instability of institutionalised moral borders. -

Gender and Power in <I>Waiting for Godot</I>

The Oswald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English Volume 18 | Issue 1 Article 3 2016 Gender and Power in Waiting for Godot Ryan Wright Reed College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor Part of the American Literature Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Literature in English, Anglophone outside British Isles and North America Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Ryan (2016) "Gender and Power in Waiting for Godot," The Oswald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English: Vol. 18 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor/vol18/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you by the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The sO wald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gender and Power in Waiting for Godot Keywords gender, power, Waiting For Godot This article is available in The sO wald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor/vol18/iss1/3 THE OSWALD REVIEW / 2016 7 Ryan Wright Reed College Gender and Power in Waiting for Godot n April of 1988, a Dutch theater company named De Haarlemse Toneelschuur began a pro- duction of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. -

Characteristics of Individuals Who Participate in Autoerotic Asphyxiation Practices: an Exploratory Study Lauren Chapple

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2018 Characteristics Of Individuals Who Participate In Autoerotic Asphyxiation Practices: An Exploratory Study Lauren Chapple Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Chapple, Lauren, "Characteristics Of Individuals Who Participate In Autoerotic Asphyxiation Practices: An Exploratory Study" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2185. https://commons.und.edu/theses/2185 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARACTERISTICS OF INDIVIDUALS WHO PARTICIPATE IN AUTOEROTIC ASPHYXIATION PRACTICES: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY by Lauren Elise Chapple, M.A. Bachelor of Arts, Bay Path University, 2007 Master of Arts, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, 2010 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Grand Forks, North Dakota August 2018 Copyright 2018 Lauren Elise Chapple ii PERMISSION Title Characteristics of Individuals Who Participate in Autoerotic Asphyxiation Practices: An Exploratory Study Department Counseling Psychology and Community Services Degree Doctor of Philosophy In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my dissertation work or, in her absence, by the Chairperson of the department or the dean of the School of Graduate Studies. -

ALWYNNE PRITCHARD Rockaby

ALWYNNE PRITCHARD Rockaby The Norwegian Naval Forces’ Band ensemble recherche SWR Experimentalstudio BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra 1999 20 YEARS 2019 ALWYNNE PRITCHARD (*1968) 1 Loser (2014) 09:28 2 March, March, March (2013) 05:41 3 Decoy (2004) 19:03 4 Rockaby (2016) 11:57 5 Graffiti (2006) 13:49 6 Glorvina (2012) 03:20 7 Irene Electric (2013) 13:03 TT 76:00 1 Klaus Steffes-Holländer, piano / voice / objects 2 The Norwegian Naval Forces’ Band Bjarte Engeset, conductor 3 ensemble recherche SWR Experimentalstudio 4 Alwynne Pritchard, voice / movement BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra Ilan Volkov, conductor 5 Christian Dierstein, percussion SWR Experimentalstudio 6 SWR Experimentalstudio 7 Victoria Johnson, violin Thorolf Thuestad, electronics Children from the Philippine High School for the Arts, voices 2 Design: Lisa Simpson 3 Gun on the Table be related too. The pianist coughs five of translation takes place in Graffi- times (should we read this as embar- ti for percussion and electronics: the rassment?) before launching, unex- sounds of drums are transformed into pectedly, into a deranged and disso- those of gongs. The drums are played nant riff that vaults across the entire through a loudspeaker set-up whose keyboard. soundwaves activate two large gongs and a tam-tam; these sounds in turn Alwynne Pritchard: I like that you no- are transformed through contact mics tice these things. Actually, I’ve revised and live electronics. the score so you don’t see the bag: the piece should now be performed behind AP: I have a need for extreme order in a curtain so only the pianist’s ankles everything I do. -

An Analysis of Starbucks As a Company and an International Business

Running head: STARBUCKS AS AN INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS 1 An Analysis of Starbucks as a Company and an International Business Lauren Roby A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2011 STARBUCKS AS AN INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Edward M. Moore, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Melanie A. Hicks, D.B.A. Committee Member ______________________________ Harvey D. Hartman, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ James H. Nutter, D.A. Honors Director ______________________________ Date STARBUCKS AS AN INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS 3 Abstract The researcher examines a detailed synopsis of the specialty coffee industry and the role that Starbucks plays in it. Starbucks is in a growth market, and it has a good relative overall position. The researcher will examine the business structure of Starbucks and the future implications of its current business strategies. By examining the strategic imperatives such as how to expand abroad and understanding the international context, the researcher will determine strong and weak business strategies of the company. Starbucks has overcome organizational and managerial implications that will serve as a strong model for international businesses. The researcher will then give strategy and implementation recommendations on how Starbucks can grow as an international business. STARBUCKS AS AN INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS 4 An Analysis of Starbucks as a Company and an International Business Introduction Millions of people all over the world walk into Starbucks every day for their cup of coffee, but it is more than the overpriced coffee that brings people in day after day to the Starbucks stores across the world. -

The Performance of Industry Culture: Assumptions, Sources And

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-1998 The Performance of Industry Culture: Assumptions, Sources and Evolutionary Patterns as Revealed in the Paradigmatic Interplay of Reporting Structures and Communicative Processes Linda Lyle University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lyle, Linda, "The Performance of Industry Culture: Assumptions, Sources and Evolutionary Patterns as Revealed in the Paradigmatic Interplay of Reporting Structures and Communicative Processes. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1998. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4590 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Linda Lyle entitled "The Performance of Industry Culture: Assumptions, Sources and Evolutionary Patterns as Revealed in the Paradigmatic Interplay of Reporting Structures and Communicative Processes." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor