Perceiving the Self in Samuel Beckett's Company and Francis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Item Is the Archived Peer-Reviewed Author-Version Of

This item is the archived peer-reviewed author-version of: Periodizing Samuel Beckett's Works A Stylochronometric Approach Reference: Van Hulle Dirk, Kestemont Mike.- Periodizing Samuel Beckett's Works A Stylochronometric Approach Style - ISSN 0039-4238 - 50:2(2016), p. 172-202 Full text (Publisher's DOI): https://doi.org/10.1353/STY.2016.0003 To cite this reference: http://hdl.handle.net/10067/1382770151162165141 Institutional repository IRUA This is the author’s version of an article published by the Pennsylvania State University Press in the journal Style 50.2 (2016), pp. 172-202. Please refer to the published version for correct citation and content. For more information, see http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.50.2.0172?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. <CT>Periodizing Samuel Beckett’s Works: A Stylochronometric Approach1 <CA>Dirk van Hulle and Mike Kestemont <AFF>UNIVERSITY OF ANTWERP <abs>ABSTRACT: We report the first analysis of Samuel Beckett’s prose writings using stylometry, or the quantitative study of writing style, focusing on grammatical function words, a linguistic category that has seldom been studied before in Beckett studies. To these function words, we apply methods from computational stylometry and model the stylistic evolution in Beckett’s oeuvre. Our analyses reveal a number of discoveries that shed new light on existing periodizations in the secondary literature, which commonly distinguish an “early,” “middle,” and “late” period in Beckett’s oeuvre. We analyze Beckett’s prose writings in both English and French, demonstrating notable symmetries and asymmetries between both languages. The analyses nuance the traditional three-part periodization as they show the possibility of stylistic relapses (disturbing the linearity of most periodizations) as well as different turning points depending on the language of the corpus, suggesting that Beckett’s English oeuvre is not identical to his French oeuvre in terms of patterns of stylistic development. -

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

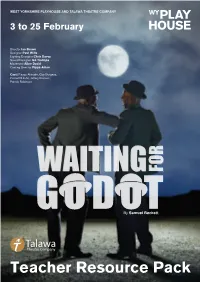

Waiting for Godot’

WEST YORKSHIRE PLAYHOUSE AND TALAWA THEATRE COMPANY 3 to 25 February Director Ian Brown Designer Paul Wills Lighting Designer Chris Davey Sound Designer Ian Trollope Movement Aline David Casting Director Pippa Ailion Cast: Fisayo Akinade, Guy Burgess, Cornell S John, Jeffery Kissoon, Patrick Robinson By Samuel Beckett Teacher Resource Pack Introduction Hello and welcome to the West Yorkshire Playhouse and Talawa Theatre Company’s Educational Resource Pack for their joint Production of ‘Waiting for Godot’. ‘Waiting for Godot’ is a funny and poetic masterpiece, described as one of the most significant English language plays of the 20th century. The play gently and intelligently speaks about hardship, friendship and what it is to be human and in this unique Production we see for the first time in the UK, a Production that features an all Black cast. We do hope you enjoy the contents of this Educational Resource Pack and that you discover lots of interesting and new information you can pass on to your students and indeed other Colleagues. Contents: Information about WYP and Talawa Theatre Company Cast and Crew List Samuel Beckett—Life and Works Theatre of the Absurd Characters in Waiting for Godot Waiting for Godot—What happens? Main Themes Extra Activities Why Godot? why now? Why us? Pat Cumper explains why a co-production of an all-Black ‘Waiting for Godot’ is right for Talawa and WYP at this time. Interview with Ian Brown, Director of Waiting for Godot In the Rehearsal Room with Assistant Director, Emily Kempson Rehearsal Blogs with Pat Cumper and Fisayo Akinade More ideas for the classroom to explore ‘Waiting For Godot’ West Yorkshire Playhouse / Waiting for Godot / Resource Pack Page 1 Company Information West Yorkshire Playhouse Since opening in March 1990, West Yorkshire Playhouse has established a reputation both nationally and internationally as one of Britain’s most exciting producing theatres, winning awards for everything from its productions to its customer service. -

Beckett and Nothing: Trying to Understand Beckett

Introduction Beckett and nothing: trying to understand Beckett Daniela Caselli Best worse no farther. Nohow less. Nohow worse. Nohow naught. Nohow on. Said nohow on. (Samuel Beckett, Worstward Ho) In unending ending or beginning light. Bedrock underfoot. So no sign of remains a sign that none before. No one ever before so – (Samuel Beckett, The Way)1 What not On 21 April 1958 Samuel Beckett writes to Thomas MacGreevy about having written a short stage dialogue to accompany the London production of Endgame.2 A fragment of a dramatic dia- logue, paradoxically entitled Last Soliloquy, has been identifi ed as being the play in question.3 However, John Pilling, in more recent research on the chronology, is inclined to date Last Soliloquy as post-Worstward Ho and pre-What Is the Word, on the basis of a letter sent by Phyllis Carey to Beckett on 3 February 1986, on the reverse of which we fi nd jottings referring to the title First Last Words with material towards Last Soliloquy.4 If we accept this new dating hypothesis, the manuscripts of this text (UoR MS 2937/1–3) – placed between two late works often associated with nothing – indicate two speakers, P and A (tentatively seen by Ruby Cohn as Protagonist and Antagonist) and two ways in which they can deliver their lines, D for declaim and A (somewhat confusingly) for normal.5 Unlike Cohn, I read A and P as standing for ‘actor’ and ‘prompter’, thus explaining why the text is otherwise puzzlingly entitled a soliloquy and supporting her hypothesis that the lines Daniela Caselli - 9781526146458 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/25/2021 06:16:53AM via free access 2 Beckett and nothing ‘Fuck the author. -

The Short Story: a Non-Definition the Short Story: a Non-Definition

THE SHORT STORY: A NON-DEFINITION THE SHORT STORY: A NON-DEFINITION By MAIRI ELIZABETH FULCHER, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University 1983 -- ---- .----- ----- MASTER OF ARTS (1983) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Short Story: A Non-Definition AUTHOR: Mairi Elizabeth Fulcher, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor L. Hutcheon NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 127 ii ABSTRACT The short story is defined, in this thesis, in terms of what it does rather than what it is. The need to transcend the limitations of brevity determines that the primary qua lity of the form is the necessity of generating a superior quality of response in the reader. Identifying this primary quality allows the critic a focus which enables him to examine the genre in terms of textual strategies specifically designed to generate reader response. This critical pers pective is open-ended and non-deterministic, and thus frees short fiction criticism from its previously prescriptive and proscriptive tendencies, which is why the definition offered here is better termed a "non-definition". iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to Professor Linda Hutcheon for the encouragement, the judicious freedom, and the rig orous criticism involved in her supervision of this thesis. Such appreciation is especially warranted in view of the fact that she graciously agreed to take over the supervision of a work in progress. Thanks is also due to Professor Graham Petrie, my original supervisor, who suggested the change of supervision, and who generously agreed to remain on my committee as a reader. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Miranda, 4 | 2011 Eleutheria―Notes on Freedom Between Offstage and Self-Reference 2

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 4 | 2011 Samuel Beckett : Drama as philosophical endgame ? Eleutheria―Notes on Freedom between Offstage and Self-reference Shimon Levy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/2019 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.2019 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Shimon Levy, “Eleutheria―Notes on Freedom between Offstage and Self-reference”, Miranda [Online], 4 | 2011, Online since 24 June 2011, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/2019 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.2019 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Eleutheria―Notes on Freedom between Offstage and Self-reference 1 Eleutheria―Notes on Freedom between Offstage and Self-reference Shimon Levy 1 Samuel Beckett’s works have long and profoundly been massaged by numerous philosophical and semi-philosophical views, methods and “isms”, ranging from Descartes, Geulincx and Malebranche to existentialism à la Sartre and Camus, to logical positivism following Frege, Wittgenstein and others―to name but a few. P. J. Murphy rightly maintains that “the whole question of Beckett’s relationship to the philosophers is pretty obviously in need of a major critical assessment”.1 In many, if not most studies, “a philosophy” has been superimposed on the -

Posthuman Beckett English 9169B Winter 2019 the Course Analyzes the Short Prose That Samuel Beckett Produced Prior to and After

Posthuman Beckett English 9169B Winter 2019 The course analyzes the short prose that Samuel Beckett produced prior to and after his monumental The Unnamable (1953), a text that initiated Beckett’s deconstruction of the human subject: The Unnamable is narrated by a subject without a fully-realized body, who inhabits no identifiable space or time, who is, perhaps, dead. In his short prose Beckett continues his exploration of the idea of the posthuman subject: the subject who is beyond the category of the human (the human understood as embodied, as historically and spatially located, as possessing some degree of subjective continuity). What we find in the short prose (our analysis begins with three stories Beckett produced in 1945-6: “The Expelled,” “The Calmative,” “The End”) is Beckett’s sustained fascination with the idea of the possibility of being beyond the human: we will encounter characters who can claim to be dead (“The Calmative,” Texts for Nothing [1950-52]); who inhabit uncanny, perhaps even post-apocalyptic spaces (“All Strange Away” [1963-64], “Imagination Dead Imagine” [1965], Lessness [1969], Fizzles [1973-75]); who are unaccountably trapped in what appears to be some kind of afterlife (“The Lost Ones” [1966; 1970]); who, in fact, may even defy even the philosophical category of the posthuman (Ill Seen Ill Said [1981], Worstward Ho [1983]). And yet despite the radical dismantling of the idea or the human, as such, the being that emerges in these texts is still, perhaps even insistently, spatially, geographically, even ecologically, located. This course which finds its philosophical inspiration in the work of Martin Heidegger, especially his critical analysis of the relation between being and world, and attempts to come to some understanding of what it means for the posthuman to be in the world. -

HCR20CD Itunes Booklet

Speak, Be Silent Riot Ensemble Chaya Czernowin Anna Thorvaldsdóttir Mirela Ivičević Liza Lim Rebecca Saunders Speak, Be Silent Riot Ensemble Kate Walter – flutes [1-6] John Garner – violin [2, 4-6] Carla Rees – flute [7] Stephen Upshaw – viola [1-6] Philip Hayworth – oboe [4-6] Louise McMonagle – violincello [1-6] Ausiàs Garrigós Morant – clarinets [1-7] Marianne Schofield – double bass [4-7] Ruth Rosales – bassoon [4-6] Adam Swayne – piano [1, 3] Amy Green – saxophone [4-6] Neil Georgeson – piano [2, 4-6] Fraser Tannock – trumpet [4-6] Claudia Maria Racovicean – piano [7] Andy Connington – trombone [4-6] Anneke Hodnett – harp [4-6] Jack Adler McKean – tuba [4-6] David Royo – percussion [1-7] Sarah Saviet – violin [1-3, soloist 4-6] Aaron Holloway-Nahum – conductor Recording venue: AIR Studios, London, 7-9 September 2018 Recording producer/mixing: Moritz Bergfeld Editing/mastering: Aaron Holloway-Nahum Booklet notes: Tim Rutherford-Johnson Chaya Czernowin, Ayre … published by Schott Music Anna Thorvaldsdóttir, Ró published by Chester Music Ltd. Mirela Ivičević, Baby Magnify/Lilith’s New Toy commissioned by the Riot Ensemble Liza Lim, Speak, Be Silent published by Casa Ricordi Rebecca Saunders, Stirrings Still II published by Edition Peters Cover photograph: Francesca Rengel Design: Mike Spikin Project management: Aaron Cassidy and Sam Gillies, CeReNeM for Huddersfield Contemporary Records (HCR) in collaboration with NMC Recordings 2 At the start of her score, Ró, the Icelandic composer Anna Thorvaldsdóttir writes to her players, ‘When you see a long sustained pitch, think of it as a fragile flower that you need to carry in your hands and walk the distance on a thin rope without dropping it or falling.’ Ró is full of such ropes. -

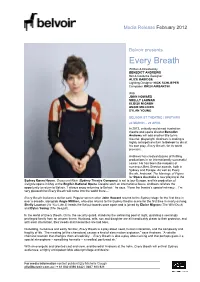

Every Breath Written & Directed by BENEDICT ANDREWS Set & Costume Designer ALICE BABIDGE Lighting Designer NICK SCHLIEPER Composer OREN AMBARCHI

Media Release February 2012 Belvoir presents Every Breath Written & Directed by BENEDICT ANDREWS Set & Costume Designer ALICE BABIDGE Lighting Designer NICK SCHLIEPER Composer OREN AMBARCHI With JOHN HOWARD SHELLY LAUMAN ELOISE MIGNON ANGIE MILLIKEN DYLAN YOUNG BELVOIR ST THEATRE | UPSTAIRS 24 MARCH – 29 APRIL In 2012, critically acclaimed Australian theatre and opera director Benedict Andrews will add another title to his résumé: playwright. Andrews is making a highly anticipated return to Belvoir to direct his own play, Every Breath, for its world premiere. Andrews has created dozens of thrilling productions in an internationally successful career. He has been the recipient of numerous Best Director awards, both in Sydney and Europe. As well as Every Breath, Andrews‟ The Marriage of Figaro for Opera Australia is now playing at the Sydney Opera House, Gross und Klein (Sydney Theatre Company) is set to tour Europe, and his production of Caligula opens in May at the English National Opera. Despite such an international focus, Andrews relishes the opportunity to return to Belvoir. „I always enjoy returning to Belvoir,‟ he says. „I love the theatre‟s special intimacy… I‟m very pleased that Every Breath will come into the world there…‟ Every Breath features a stellar cast. Popular screen actor John Howard returns to the Sydney stage for the first time in over a decade, alongside Angie Milliken, who also returns to the Sydney theatre scene for the first time in nearly as long. Shelly Lauman (As You Like It) treads the Belvoir boards once again and is joined by Eloise Mignon (The Wild Duck) and Dylan Young (The Seagull). -

BECKETT and the QUEST for MEANING Martin Esslin The

BECKETT AND THE QUEST FOR MEANING Martin Esslin The twentieth century has been a turbulent and unhappy age, dominated by fanaticisms, ideologies that proclaimed themselves as infallibly based on would-be scientific truths about race or class, and in consequence a period of unprecedented violence and cruelty. In those distant days, in nineteen-thirties Vienna, when as a school boy I joined an underground Communist cell and was, in hidden clear ings in the woods on summer Sundays, indoctrinated in the principles of Marxism, I learned that this system of thought had now become a scien tific truth beyond doubt, and that therefore anyone who wanted to pursue policies that contradicted it had to be liquidated for the general good. (It was the period of the great Moscow trials.) At the same time, some of my friends at school who belonged to the equally illegal and underground Hitler youth assured me that inferior races like the Jews had been scien tifically established as being so noxious to the future health of humanity that it was an urgent necessity to kill them all, not realizing that I, their friend, was included in this verdict. Those totalitarian creeds are now in disrepute, but the world is still threatened by violent fanaticisms and fundamentalisms of numerous varieties: the vacuum created by the decline of traditional religious be liefs in the nineteenth century, still far from having been filled, has grown ever wider as it has become less and less possible to accept the literal truth of events like the Resurrection. Those who still cling to them revert to the primitivism of fundamentalist cults; most others are left with an equally primitive, stultifying and barren materialism. -

Collected Shorter Plays of Samuel Beckett Murphy

Collected Shorter Plays Works by Samuel Beckett published by Grove Press Cas cando Mercier and Camier Collected Poems in Molloy English and French More Pricks Than Kicks The Collected Shorter Plays of Samuel Beckett Murphy Company Nohow On (Company, Seen Disjecta Said, Worstward Ho) Endgame Ill Ohio Impromptu Ends and Odds Ill Proust First Love and Other Stories Rockaby Happy Days Stories and Texts How It Is for Nothing I Can't Go On, I'll Go On Three Novels Krapp Last Tape Waiting for Godot The Lost Ones Watt s Malone Dies Worstward Ho Happy Days: Samuel Beckett's Production Notebooks, edited by James Knowlson Samuel Beckett: The Complete Short Prose, 1929-/989, edited and with an introduction and notes by S. E. Gontarski The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beckett: Endgame, edited by S. E. Gontarski The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beckett: Krapp's Last Tape, edited by James Knowlson The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beckett: Waiting for Godot, edited by Dougald McMillan and James Knowlson COLLECTED SHORTER PLAYS SAMUEL BECKETT Grove Press New York Copyright© 1984 by Samuel Beckett All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying,recording, or otherwise,without prior written permission of the publisher. Grove Press 841 Broadway New York, NY 10003 All That Fall © Samuel Beckett, 1957; Act Without Words I © Samuel Beckett, 1959; Act Without Words II© Samuel Beckett,1959; Krapp's Last 'Ihpe© Samuel Beckett,1958; Rough for Theatre I © Samuel Beckett, 1976; Rough for Theatre II© Samuel Beckett,1976; Embers © Samuel Beckett,1959; Rough for Radio I© Samuel Beckett,1976; Rough forRadio II© Samuel Beckett, 1976; Words and Music © Samuel Beckett,1962; Cascando© Samuel Beckett, 1963; Play © Samuel Beckett, 1963; Film © Samuel Beckett, 1967; The Old Tune, adapt.