Beckett's Manipulation of Audience Response in Waiting for Godot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

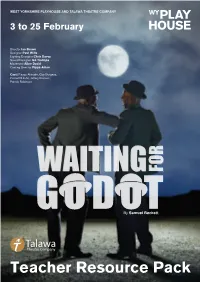

Waiting for Godot’

WEST YORKSHIRE PLAYHOUSE AND TALAWA THEATRE COMPANY 3 to 25 February Director Ian Brown Designer Paul Wills Lighting Designer Chris Davey Sound Designer Ian Trollope Movement Aline David Casting Director Pippa Ailion Cast: Fisayo Akinade, Guy Burgess, Cornell S John, Jeffery Kissoon, Patrick Robinson By Samuel Beckett Teacher Resource Pack Introduction Hello and welcome to the West Yorkshire Playhouse and Talawa Theatre Company’s Educational Resource Pack for their joint Production of ‘Waiting for Godot’. ‘Waiting for Godot’ is a funny and poetic masterpiece, described as one of the most significant English language plays of the 20th century. The play gently and intelligently speaks about hardship, friendship and what it is to be human and in this unique Production we see for the first time in the UK, a Production that features an all Black cast. We do hope you enjoy the contents of this Educational Resource Pack and that you discover lots of interesting and new information you can pass on to your students and indeed other Colleagues. Contents: Information about WYP and Talawa Theatre Company Cast and Crew List Samuel Beckett—Life and Works Theatre of the Absurd Characters in Waiting for Godot Waiting for Godot—What happens? Main Themes Extra Activities Why Godot? why now? Why us? Pat Cumper explains why a co-production of an all-Black ‘Waiting for Godot’ is right for Talawa and WYP at this time. Interview with Ian Brown, Director of Waiting for Godot In the Rehearsal Room with Assistant Director, Emily Kempson Rehearsal Blogs with Pat Cumper and Fisayo Akinade More ideas for the classroom to explore ‘Waiting For Godot’ West Yorkshire Playhouse / Waiting for Godot / Resource Pack Page 1 Company Information West Yorkshire Playhouse Since opening in March 1990, West Yorkshire Playhouse has established a reputation both nationally and internationally as one of Britain’s most exciting producing theatres, winning awards for everything from its productions to its customer service. -

The Short Story: a Non-Definition the Short Story: a Non-Definition

THE SHORT STORY: A NON-DEFINITION THE SHORT STORY: A NON-DEFINITION By MAIRI ELIZABETH FULCHER, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University 1983 -- ---- .----- ----- MASTER OF ARTS (1983) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Short Story: A Non-Definition AUTHOR: Mairi Elizabeth Fulcher, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor L. Hutcheon NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 127 ii ABSTRACT The short story is defined, in this thesis, in terms of what it does rather than what it is. The need to transcend the limitations of brevity determines that the primary qua lity of the form is the necessity of generating a superior quality of response in the reader. Identifying this primary quality allows the critic a focus which enables him to examine the genre in terms of textual strategies specifically designed to generate reader response. This critical pers pective is open-ended and non-deterministic, and thus frees short fiction criticism from its previously prescriptive and proscriptive tendencies, which is why the definition offered here is better termed a "non-definition". iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to Professor Linda Hutcheon for the encouragement, the judicious freedom, and the rig orous criticism involved in her supervision of this thesis. Such appreciation is especially warranted in view of the fact that she graciously agreed to take over the supervision of a work in progress. Thanks is also due to Professor Graham Petrie, my original supervisor, who suggested the change of supervision, and who generously agreed to remain on my committee as a reader. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

The Search for Meaning in Waiting for Godot

Praxis: The Journal for Theatre, Performance Studies, and Criticism 2013 Issue Deconstructing Consciousness: The Search for Meaning in Waiting for Godot Dan Ciba Samuel Beckett has long been recognized as a great playwright of the Theater of the Absurd, a theatrical genre identified by dramatic critic Martin Esslin. Early Absurdist playwrights were categorized by Esslin because of their use of narrative and character in order to expose the meaninglessness of a post-Nietzschean world. In his book the Theatre of the Absurd, Esslin states: “'Absurd' originally means 'out of harmony', in a musical context. Hence its dictionary definition: 'out of harmony with reason or propriety; incongruous, unreasonable, illogical'[...] In an essay on Kafka, Ionesco defined his understanding of the term as follows: 'Absurd is that which is devoid of purpose... Cut off from his religious, metaphysical, and transcendental roots, man is lost; all his actions become senseless, absurd, useless” (Esslin 1973, p.5). Because Esslin used Beckett as his first example, an Absurdist reading of Waiting for Godot has already been well explored by scholars and practitioners. Another popular reading is deeply rooted in the existential struggle of humanity after World War II. A deconstruction of this play offers the potential to explore Beckett beyond the existential and Absurdist readings that critics and audiences typically use to understand Beckettian plays. This paper examines Godot through a post-structural lens. By integrating the theoretical concept of deconstruction suggested by Jacques Derrida with the psychoanalytic theories of Jacques Lacan's symbolic language, I seek to identify and interpret the symbols in this play as signifiers. -

The Material of Film and the Idea of Cinema: Contrasting Practices in Sixties and Seventies Avant-Garde Film*

The Material of Film and the Idea of Cinema: Contrasting Practices in Sixties and Seventies Avant-Garde Film* JONATHAN WALLEY I In 1976, the American Federation of Arts organized a major program of American avant-garde films made since the early 1940s. In his introduction to the program’s catalog, Whitney film curator and series organizer John Hanhardt argued that the central preoccupation of filmmakers across the history of avant-garde cinema had been with the exploration of the material properties of the film medium itself: “This cinema subverts cinematic convention by exploring its medium and its properties and materials, and in the process creates its own history separate from that of the classical narrative cinema. It is filmmaking that creates itself out of its own experience.”1 Having traced the history of avant-garde film according to the modernist notion that an art form advances by reflexively scrutinizing the “properties and materials” of its medium, Hanhardt turned his attention to more recent developments. But these new developments were not entirely receptive to his modernist model. On the one hand, he argued, filmmakers were continuing to create works that engaged the physical materials of film—film strip, projector, camera, and screen—and the range of effects these made possible. On the other, this engagement appeared to be leading some filmmakers to create cinematic works challenging the material limits of the film medium as it had been defined for over eighty years. For example, in Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone (1973), the focus of the viewer’s attention was not an image projected onto a screen, but the projector beam itself, which over the course of thirty minutes grew from a thin line of light to a cone—a three-dimensional light sculpture with which the viewer could interact. -

Thesis-Time-In-Beckett.Pdf

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Miriam Zbíralová Time in the Plays of Samuel Beckett Bachelor‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph. D. 2010 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author‟s signature I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D., for his valuable advice during the whole process of writing the thesis. Table of Contents: Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 5 1 Time and the Performance ............................................................................................. 6 1.1 The Unity of Time and Fictional versus Performance Time .................................. 6 1.2 Tempo ..................................................................................................................... 8 2 Time and the Structure of the Plays ............................................................................. 11 2.1 Cyclical Development ........................................................................................... 11 2.2 Suspense ................................................................................................................ 14 3 Time and the Characters .............................................................................................. 16 3.1 The Past and the Future -

Modes of Being and Time in the Theatre of Samuel Beckett

f.'lODES Ol!' BEING AND TIME IN THE THEATRE OF SANUEL BECKETT MODES OF BEING AND TIME IN THE THEATRE OF SAMUEL BECKETT By ANNA E.V. PRETO, B.A., LICENCE ES LETTRES A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree TvIaster of Arts !-1cMaster Uni versi ty October 1974 MASTER OF ARTS (1974) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (Romance Languages) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Modes of Being and Time in the Theatre of Samuel Beckett AUTHOR: Anna E.V. Preto, B.A. (University of British Columbia) Licence es Lettres (Universite de Grenoble) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Brian S. Pocknell NUNBER OF PAGES: vi, 163 ii AKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Dr. Brian S. Pocknell for his interest, his encouragement and counsel in the patient supervision of this dissertation. I also wish to thank McMaster University for its generous financial assistance. iii CONTENTS I An Introduction to the Beckett Situation 1 II Being on the Threshold to Eternity: Waiting for Godot and Endgame 35 III The Facets of the Prism: Beckett's Remaining Plays 74 IV The Language of the Characters and Time 117 Conclusion 147 Bibliography 153 iv PREFACE Beckett as an author has inspired an impressive range of critical studies to date. The imposing amounts of critical material bear witness to the richness of his writings, which present a wealth of themes and techniques. His plays concentrate for us the problem-themes that already concerned him in his earlier prose works, and bring them to the stage in a more streamlined form. The essential problem which evolves from Beckett's own earlier writings comes to the fore, downstage, in the plays: it is that of being in time, a purgatorial state, the lot of mankind and of Beckett's characters, who are representative of mankind. -

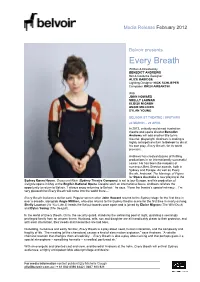

Every Breath Written & Directed by BENEDICT ANDREWS Set & Costume Designer ALICE BABIDGE Lighting Designer NICK SCHLIEPER Composer OREN AMBARCHI

Media Release February 2012 Belvoir presents Every Breath Written & Directed by BENEDICT ANDREWS Set & Costume Designer ALICE BABIDGE Lighting Designer NICK SCHLIEPER Composer OREN AMBARCHI With JOHN HOWARD SHELLY LAUMAN ELOISE MIGNON ANGIE MILLIKEN DYLAN YOUNG BELVOIR ST THEATRE | UPSTAIRS 24 MARCH – 29 APRIL In 2012, critically acclaimed Australian theatre and opera director Benedict Andrews will add another title to his résumé: playwright. Andrews is making a highly anticipated return to Belvoir to direct his own play, Every Breath, for its world premiere. Andrews has created dozens of thrilling productions in an internationally successful career. He has been the recipient of numerous Best Director awards, both in Sydney and Europe. As well as Every Breath, Andrews‟ The Marriage of Figaro for Opera Australia is now playing at the Sydney Opera House, Gross und Klein (Sydney Theatre Company) is set to tour Europe, and his production of Caligula opens in May at the English National Opera. Despite such an international focus, Andrews relishes the opportunity to return to Belvoir. „I always enjoy returning to Belvoir,‟ he says. „I love the theatre‟s special intimacy… I‟m very pleased that Every Breath will come into the world there…‟ Every Breath features a stellar cast. Popular screen actor John Howard returns to the Sydney stage for the first time in over a decade, alongside Angie Milliken, who also returns to the Sydney theatre scene for the first time in nearly as long. Shelly Lauman (As You Like It) treads the Belvoir boards once again and is joined by Eloise Mignon (The Wild Duck) and Dylan Young (The Seagull). -

The Element of Time in Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett

Journal of World Englishes and Educational Practices (JWEEP) ISSN: 2707-7586 DOI: 10.32996/jweep Journal Homepage: www.al-kindipublisher.com/index.php/jweep The Element of Time in Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett Shazia Abid M. Phil English (Literature & Linguistics) Department of English Studies, Qurtuba University 2017, Pakistan Corresponding Author: Shazia Abid, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Received: March 05, 2021 Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1952) is one of the most puzzling plays of the Accepted: April 18, 2021 modern era. It is a play where nothing happens twice. Hence, the purpose of this Volume: 3 research paper to explore the element of time in Beckett’s masterpiece Waiting for Issue: 4 Godot (tragicomedy). The play is part of the ‘Theatre of Absurd’ and being an DOI: 10.32996/jweep.2021.3.4.3 absurdist playwright, Beckett tends to explore the internal states of individual’s mind. It also explores the absurdity of modern man that how they are dwelling in a twilight KEYWORDS state and unaware of their surroundings. This work is based on the belief that the universe is irrational, meaningless and the search for order brings the individuals into waiting, absurdism, loneliness, conflict with the universe. The study investigates existentialist’s point of views. In the existentialism, despair, physical play ‘Time’ represents very much dominating force as well as a tormenting tool to its suffering, nothingness, time characters. 1. Introduction 1 Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot is a well-known drama of twentieth-century literature. He created completely a new kind of play and exhibits trepidation of human beings using comic style. -

Erican Historical Association, Washington D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 310 025 SO 020 106 AUTHOR O'Connor, John E. TITLE Teaching History with Film and Television. Discussions on Teaching, Number 2. INSTITUTION American Historical Association, Washington D.C. SPANS AGENCY National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-87229-040-9 PUB DATE 87 NOTE 94p.; Contains photographs that may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROMAmerican Historical Association, 400 4 Street, 3E, Washington, DC 20003 ($3.50 plus $1.00 for shipping and handling). PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Critical Thinking; Curriculum Enrichment; *Films; *History Instruction; Secondary Education; Social Studies; *Television; Television Viewing; Videotape Recordings; *Visual Literacy IDENTIFIERS Film Aesthetics; *Film History; *Film Theory ABSTRACT History teachers should be less concerned with having students try to re-experience the past and more concerned with teaching them how to learn from the study of it. Keeping this in mind, teachers should integrate more critical film and television analysis into their history classes, but not in place of reading or at the expense of traditional approaches. Teachers must show students how to engage, rather than suspend, their critical faculties when the projector or television monitor is turned on. The first major section of this book, "Analyzing a Moving Image as a Historical Document," discusses the two stages in the analysis of a moving image document: (1) a general analysis of content, production, and reception; and (2) the study of the moving image document as a representation of history, as evidence for social and cultural history, as evidence for historical fact, or as evidence for the history of film and television. -

Samuel Beckett's Krapp's Last Tape

Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape: Remembering Kant, Forgetting Proust I wrote recently, in English, a short stage monologue (20 minutes) of which Time is the indubitable villain. — Samuel Beckett (Letters 3: 155)1 I The first volume of Samuel Beckett’s letters from the period 1929–40 provides new insights into Beckett’s intricate relationship with the writings of Marcel Proust, a relationship that has commonly been mediated through Beckett’s early academic study Proust, written in 1930 and published in 1931.2 Beckett’s letters to Thomas McGreevy during the preparation of Proust lament both the duration of reading necessitated by Proust’s monumental work – “And to think that I have to contemplate him at stool for 16 volumes!” (Letters 1: 12) – and a subsequent race against time to write the monograph. In July 1930, Beckett reported, “I can’t start the Proust. Curse this hurry any how. [. .] At least I have finished reading the bastard” (1: 26). By September, time is again of the essence: “I am working all day & most of the night to get this fucking Proust finished” (1: 46; emphasis in original). In preference to working on Proust in July 1930, Beckett was “reading Schopenhauer. Everyone laughs at that,” although his motivation was contemplation of an “intellectual justification of unhappiness – the greatest that has ever been attempted” (1: 32–33). Beckett insisted that “I am not reading philosophy, nor caring whether he is right or wrong or a good or worthless metaphysician” (1: 33). Whether they are right or wrong or even qualify as philosophy at all, the prefaces to the first and second editions of Arthur Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation (1818 and 1844, respectively) were certainly read by Beckett.