How Bigger Was Born Anew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

Unraveling Native Son: Propagating Communism) Racial Hatred) Societal Change Or None of the Above??

IUSB Graduate Journal Ill 1 Unraveling Native Son: Propagating Communism) Racial Hatred) Societal Change or None of the Above?? by:jacqueline Becker Department of English ABSTRACT: This paper explores the many different ways in which Communism is portrayed within Richard Wright's novel Native Son. It also seeks to illustrate that regardless of the reasoning behind the conflicted portrayal of Communism, within the text, it does serve a vital purpose, and that is to illustrate to the reader that there is no easy answer or solution for the problems facing society. Bigger and his actions cannot be simply dismissed as a product of a damaged society, nor can Communism be seen as an all-encompassing saving grace that will fix all of societies woes. Instead, this novel, seeks to illustrate the type of people that can be produced in a society divided by racial class lines. It shows what can happen when one oppressed group feels as though they have no power over their own lives. I have attempted to illustrate that what Wright ultimately achieved, through his novel Native Son, is to illuminate to readers of the time that a serious problem existed within their society, specifically in Chicago within the "Black Belt" and that the solution lies not with one social group or political party, not through senseless violence, but rather through changes in policy. ~Research~ 2 lll Jacqueline Becker Unraveling Native Son: Propagating Communism) Racial Hatred) Societal Change or None of the Above?? ichard Wright's novel, Native Son, presents Communism in many different lights. On the one hand, the pushy nature R of Jan and Mary, two white characters trying to share their beliefs about an equal society under Communism, by forcing Bigger, the black protagonist, to dine and drink with them, is ultimately what leads to Mary's death. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison: Conflicting Masculinities

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison: Conflicting Masculinities H. Alexander Nejako College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Nejako, H. Alexander, "Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison: Conflicting Masculinities" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625892. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nehz-v842 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RICHARD WRIGHT AND RALPH ELLISON: CONFLICTING MASCULINITIES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by H. Alexander Nejako 1994 ProQuest Number: 10629319 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10629319 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Materiality and Masculinity in African American Literature. (2014) Directed by Dr

GIBSON, SCOTT THOMAS, Ph.D. Heavy Things: Materiality and Masculinity in African American Literature. (2014) Directed by Dr. SallyAnn H. Ferguson. 222 pp. Heavy Things illustrates how African American writers redefine black manhood through metaphors of heaviness, figured primarily through their representation of material objects. Taking the literal and figurative weight the narrator’s briefcase in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man as a starting point, this dissertation examines literary representations of material objects, including gifts, toys, keepsakes, historical documents, statues, and souvenirs as modes of critiquing the materialist foundations of manhood in the United States. Historically, materialism has facilitated white male domination over black men by associating property ownership with both whiteness and manhood. These writers not only reject materialism as a vehicle of oppression but also reveal alternative paths along which black men can thrive in a hostile American society. Each chapter of my analysis is structured around specific kinds of “heavy” objects—gifts, artifacts, and memorials—that liberate black men from white definitions of manhood based in possessive materialism. In Frederick Douglass’s Narrative and Ernest Gaines’s A Lesson Before Dying, gifts reestablished ties between alienated black men and their communities. In Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon and John Edgar Wideman’s Fatheralong, black sons attempt to reconcile their fraught relationships with their fathers through the recovery of historical artifacts. In Colson Whitehead’s John Henry Days and Emily Raboteau’s The Professor’s Daughter, black men and women use commemorative objects such as monuments and memorials to reimagine black male abjection as a trope of healing. -

Simply Folk Sing-Along 2018 If I Had a Hammer If I Had a Hammer, I'd Hammer in the Morning, I'd Hammer in the Evening, All Over

Simply Folk Sing-Along 2018 If I Had a Hammer If I had a hammer, I'd hammer in the morning, I'd hammer in the evening, all over this land I'd hammer out danger, I'd hammer out a warning I'd hammer out love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land If I had a bell, I'd ring it in the morning, I'd ring it in the evening, all over this land I'd ring out danger, I'd ring out a warning I'd ring out love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land If I had a song, I'd sing it in the morning, I'd sing it in the evening, all over this land I'd sing out danger, I'd sing out a warning I'd sing out love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land Well I've got a hammer, and I've got a bell, and I've got a song to sing, all over this land It's the hammer of justice, it's the bell of freedom It's the song about love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land You Are My Sunshine The other night dear as I lay sleeping, I dreamed I held you in my arms, But when I woke dear I was mistaken, and I hung my head and I cried You are my sunshine, my only sunshine, you make me happy when skies are gray, You'll never know dear, how much I love you, please don't take my sunshine away I'll always love you and make you happy, if you will only say the same, But if you leave me and love another, you’ll regret it all someday You told me once dear, you really loved me, and no one could come between, But now you've left me to love another, you have shattered all of my dreams In all my dreams, dear, you seem to leave me; when I awake my poor heart pains So won’t you come back and make me happy, I’ll forgive, dear, I’ll take all the blame City of New Orleans Riding on the City of New Orleans, Illinois Central Monday morning rail Fifteen cars and fifteen restless riders, three conductors and twenty-five sacks of mail. -

Native Son (Questions)

Native Son (Questions) 1 Wright writes of Bigger Thomas: “these were the rhythms of his life; indifference and violence; periods of abstract brooding and periods of intense desire; moments of silence and moments of anger” … Does Wright intend us to relate to Bigger as a human being – or has he deliberately made him an embodiment of oppressive social and political forces? Is there anything admirable about Bigger? Does he change by the end of the book? 2 James Baldwin, an early protégé of Wright’s, later attacked the older writer for his self-righteousness and reliance on stereo-types… In his famous essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel” Baldwin compared Bigger to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom, and dismissed Native Son as “protest” fiction. Do you agree? 3 When Bigger stands confronted by his family in jail, he thinks… they ought to be glad he was a murderer; “had he not taken on himself the crime of being black?” Talk about Bigger as a victim and sacrificial figure. If Wright wanted us to pity Bigger, why did he portray him as so brutal? 4 How dated does this book seem in its depiction of racial hatred and guilt? Have we as a society moved beyond the rage and hostility that Wright depicts between blacks and whites? Or are we still living in a culture that could produce a figure like Bigger Thomas? https://www.litlovers.com/reading-guides/fiction/719-native-son-wright?start=3 Native Son (About the Author) Author: Richard Wright Born: September 4, 1908 Where: near Natchez, MS Education: Smith-Robertson Junior High, Jackson MS Died: November 28, 1960 Where: Paris, France Richard Wright was the first 20th century African-American writer to command both critical acclaim and popular success. -

Paul Green Foundation

Paul Green Foundation NEWS – October 2017 Native Son’s New Adaptation PAUL GREEN ANNUAL MEETING Playwright Nambi Kelley NOVEMBER 4, 2017 has written plays for NC BOTANICAL GARDEN Steppenwolf, Goodman Theatre and Lincoln Center CHAPEL HILL, NC and most recently was named playwright-in-residence at The 2017 the National Black Theatre in New York. Kelley’s adaptation of Native Son was National Theatre Conference presented to critical acclaim for the premiere December 1-3 in New York City production at the Court Theatre/American Blues Each year the National Theatre Conference Festival. Since that first production it has been Person of the Year names the Paul Green produced in New York, California, Georgia and Award winner. This year’s Person of the Year – Arizona, and published by Samuel French in 2016. Molly Smith selected June Schreiner, a highly The Green Foundation joined with the Wright acclaimed young actor. Since 1989, the Paul Estate to sanction these productions. Green Foundation has honored a “young theatre professional” with this Paul Green Award. A bit of history: Paul Green and Richard Wright’s Native Son that opened on March 24, Founded in 1925, the National Theatre 1941, at the St. James Theatre in New York City, Conference is a not-for-profit organization made was produced by Orson Welles and John up of distinguished members of the American Houseman. Of the very serious disagreement that Theatre Community; Green was instrumental in ensued between Green and Wright, Dr. Laurence the founding the organization and served as Avery, Professor Emeritus, UNC-Chapel Hill president in the early years. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Citizen Kane Ebook, Epub

CITIZEN KANE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Harlan Lebo | 368 pages | 01 May 2016 | Thomas Dunne Books | 9781250077530 | English | United States Citizen Kane () - IMDb Mankiewicz , who had been writing Mercury radio scripts. One of the long-standing controversies about Citizen Kane has been the authorship of the screenplay. In February Welles supplied Mankiewicz with pages of notes and put him under contract to write the first draft screenplay under the supervision of John Houseman , Welles's former partner in the Mercury Theatre. Welles later explained, "I left him on his own finally, because we'd started to waste too much time haggling. So, after mutual agreements on storyline and character, Mank went off with Houseman and did his version, while I stayed in Hollywood and wrote mine. The industry accused Welles of underplaying Mankiewicz's contribution to the script, but Welles countered the attacks by saying, "At the end, naturally, I was the one making the picture, after all—who had to make the decisions. I used what I wanted of Mank's and, rightly or wrongly, kept what I liked of my own. The terms of the contract stated that Mankiewicz was to receive no credit for his work, as he was hired as a script doctor. Mankiewicz also threatened to go to the Screen Writers Guild and claim full credit for writing the entire script by himself. After lodging a protest with the Screen Writers Guild, Mankiewicz withdrew it, then vacillated. The guild credit form listed Welles first, Mankiewicz second. Welles's assistant Richard Wilson said that the person who circled Mankiewicz's name in pencil, then drew an arrow that put it in first place, was Welles. -

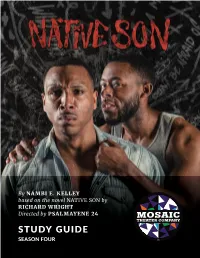

STUDY GUIDE SEASON FOUR Introduction

By NAMBI E. KELLEY based on the novel NATIVE SON by RICHARD WRIGHT Directed by PSALMAYENE 24 STUDY GUIDE SEASON FOUR Introduction “Theatre is a form of knowledge; it should and can also be a means of transforming society. Theatre can help us build our future, rather than just waiting for it.”—Augusto Boal The purpose and goal of Mosaic’s education department is simple. Our program aims to further and cultivate students’ knowledge and passion for theatre and theatre education. We strive for complete and exciting arts engagement for educators, artists, our community, and all learners in the classroom. Mosaic’s education program yearns to be a conduit for open discussion and connection to help students understand how theatre can make a profound impact in their lives, in society, and in their communities. Mosaic Theater Company of DC is thrilled to have your interest and support! Catherine Chmura Arts Education Apprentice—Mosaic Theater Company of DC Written by Catherine Chmura, Khalid Y. Long, and Isaiah M. Wooden 2 NATIVE SON MOSAIC THEATER COMPANY of DC PRESENTS NATIVE SON By Nambi E. Kelley based on the novel NATIVE SON by Richard Wright Directed by Psalmayene 24 Set Designer: Ethan Sinnott Lighting Designer: William K. D’Eugenio Costume Designer: Katie Touart Projections Designer: Dylan Uremovich Sound Designer: Nick Hernandez Properties Designer: Willow Watson Movement Specialist: Tony Thomas* Production Stage Manager: Simone Baskerville* Dramaturg: Isaiah M. Wooden & Khalid Yaya Long Table of Contents Curriculum Connections: DC Public -

Richard Wright and His Anxious Influence: on Ellison and Baldwin

Richard Wright and his Anxious Influence: On Ellison and Baldwin And in this lies Wright's most important achievement: he has converted the American Negro impulse toward self-annihilation and "going underground" into a will to confront the world, to evaluate his experience honestly, and throw his findings unashamedly into the guilty conscience of America. – Ralph Ellison, “Richard Wright’s Blues” In Uncle Tom’s Children, in Native Son, and, above all, in Black Boy, I found expressed for the first time in my life, the sorrow, the rage, and the murderous bitterness which was eating up my life and the lives of those around me. His work was an immense liberation and revelation for me. He became my ally and my witness, and alas! my father. – James Baldwin, “Alas, Poor Richard” It is not easy being a father. Sigmund Freud was right, no matter how bizarre his evidential sources: the children will come for you. To be a father is to have children, to have them under your gaze, but also to set them freer than you may have ever intended. Fatherly authority is defined, in many ways, by the insistence of his subjects on the rights of refusal, contestation, and overcoming. That is what it means to have children. They are yours, if you are the father. They inherit you. But they also belong to themselves. And that belonging-to-self thing is largely generated by struggle, opposition, and overcoming. Parricide. Richard Wright is in this way very much the father of two of the most important African- American writers writing in his shadow: James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison.