What Warhol Saw When He Looked at Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andy Warhol From

Andy Warhol From “THE HOUSE THAT went to TOWN” 8 February - 9 March 2019 I. Andy Warhol “Dancing Sprites”, ca. 1953 ink and watercolor on paper 73.7 x 29.5 cm (framed: 92.7 x 48.4 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1953/23 Andy Warhol “Sprite Acrobats”, ca. 1956 ink on paper, double-sided 58.5 x 73.5 cm (framed: 92.4 x 77.5 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1956/08 Andy Warhol “Sprite Figures Kissing”, ca. 1951 graphite on paper 14.3 x 21.6 cm (framed: 32.2 x 39.5 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1951/01 Warhol used this motif in several illustrations from the early 1950s: for an anonymous article entitled “Romantic Possession” (publication unknown, c. 1950) and for Weare Holbrook’s “Women – What To Do With Them”, Park East (March 1952), p. 26. See Paul Maréchal, Andy Warhol: The Complete Commissioned Magazine Work, 1948- 1987: A Catalogue Raisonné (Munich: Prestel, 2014), pp. 30, 50. Andy Warhol “Female Sprite”, ca. 1954 graphite on paper, double-sided 27.9 x 21.6 cm (framed: 46 x 39.7 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1954/05 Andy Warhol “Sprite Head with Feet”, ca. 1953 ink on paper 27.9 x 21.5 cm (framed: 46 x 39.7 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1953/24 Andy Warhol “Sprite Portrait with Shoes”, ca. 1953 ink on paper 27.8 x 21.5 cm (framed: 46 x 39.7 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1953/25 II. Andy Warhol “The House That Went To Town”, 1952-1953 graphite, ink and tempera on paper 27.7 x 21.7 cm (framed: 46 x 39.7 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1956/25 The likely prototype for Warhol and Corkie’s “THE HOUSE THAT went to TOWN” is Virginia Lee Burton’s celebrated children’s book The Little House, first published in 1942. -

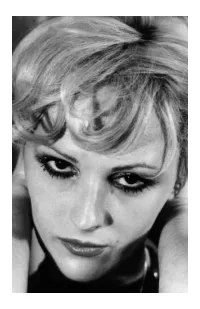

Moma Andy Warhol Motion Pictures

MoMA PRESENTS ANDY WARHOL’S INFLUENTIAL EARLY FILM-BASED WORKS ON A LARGE SCALE IN BOTH A GALLERY AND A CINEMATIC SETTING Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures December 19, 2010–March 21, 2011 The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art Gallery, sixth floor Press Preview: Tuesday, December 14, 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. Remarks at 11:00 a.m. Click here or call (212) 708-9431 to RSVP NEW YORK, December 8, 2010—Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures, on view at MoMA from December 19, 2010, to March 21, 2011, focuses on the artist's cinematic portraits and non- narrative, silent, and black-and-white films from the mid-1960s. Warhol’s Screen Tests reveal his lifelong fascination with the cult of celebrity, comprising a visual almanac of the 1960s downtown avant-garde scene. Included in the exhibition are such Warhol ―Superstars‖ as Edie Sedgwick, Nico, and Baby Jane Holzer; poet Allen Ginsberg; musician Lou Reed; actor Dennis Hopper; author Susan Sontag; and collector Ethel Scull, among others. Other early films included in the exhibition are Sleep (1963), Eat (1963), Blow Job (1963), and Kiss (1963–64). Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures is organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Chief Curator at Large, The Museum of Modern Art, and Director, MoMA PS1. This exhibition is organized in collaboration with The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Twelve Screen Tests in this exhibition are projected on the gallery walls at large scale and within frames, some measuring seven feet high and nearly nine feet wide. An excerpt of Sleep is shown as a large-scale projection at the entrance to the exhibition, with Eat and Blow Job shown on either side of that projection; Kiss is shown at the rear of the gallery in a 50-seat movie theater created for the exhibition; and Sleep and Empire (1964), in their full durations, will be shown in this theater at specially announced times. -

Warhol, Andy (As Filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol

Warhol, Andy (as filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol. by David Ehrenstein Image appears under the Creative Commons Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy Jack Mitchell. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com As a painter Andy Warhol (the name he assumed after moving to New York as a young man) has been compared to everyone from Salvador Dalí to Norman Rockwell. But when it comes to his role as a filmmaker he is generally remembered either for a single film--Sleep (1963)--or for works that he did not actually direct. Born into a blue-collar family in Forest City, Pennsylvania on August 6, 1928, Andrew Warhola, Jr. attended art school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. He moved to New York in 1949, where he changed his name to Andy Warhol and became an international icon of Pop Art. Between 1963 and 1967 Warhol turned out a dizzying number and variety of films involving many different collaborators, but after a 1968 attempt on his life, he retired from active duty behind the camera, becoming a producer/ "presenter" of films, almost all of which were written and directed by Paul Morrissey. Morrissey's Flesh (1968), Trash (1970), and Heat (1972) are estimable works. And Bad (1977), the sole opus of Warhol's lover Jed Johnson, is not bad either. But none of these films can compare to the Warhol films that preceded them, particularly My Hustler (1965), an unprecedented slice of urban gay life; Beauty #2 (1965), the best of the films featuring Edie Sedgwick; The Chelsea Girls (1966), the only experimental film to gain widespread theatrical release; and **** (Four Stars) (1967), the 25-hour long culmination of Warhol's career as a filmmaker. -

August 2018 Vol

August 2018 vol. 41 no. 7 Providing fitness and community for individuals and families through physical, educational, cultural, and social programs th 7 Annual Czech that Film! Bringing the Best New Czech Films to North America Presented in collaboration with the Consulate General UPCOMING EVENTS of the Czech Republic in Los Angeles, Czech That Film is a series showcasing the best of Czech cinema. 2018 September Slovo Deadline It is committed to exhibiting films that not only expose August1,2018 participants to Czech culture, but also enlighten audiences, bring people together, and present inspired Board of Trustees Meeting entertainment for all. 100 YEARS August8,7p.m. OF CZECHOSLOVAK Supporting the film series locally are Czech and CINEMA Slovak Sokol Minnesota, Czech and Slovak Cultural Slovak Architect for all Center of Minnesota, Czech & Slovak School Twin Seasons Lecture Cities, Marshall Toman, Honorary Czech Consul M. L. Kucera, plus others. RecognizingDušanJurkovič Friday, August 24, 9:30 p.m. 8 HEADS OF MADNESS / 8 HLAV ŠÍLENSTVÍ . Directed August11,11a.m. by Marta Nováková, 2017, 107 minutes. Follow the life of the talented Russian poet Anna Barkova (1906–1976), who spent twenty-two years of her life in the Gulag. Board of Directors Meeting Saturday, August 25, 4:00 p.m. MILADA / MILADA . Directed by David Mrnka, 2017, 124 minutes. This historical drama is based on the true story of Milada Horáková, a woman August16,7p.m. executed on the basis of fabricated charges of conspiracy and treason in a political show trial by the communist regime in the former Czechoslovakia. -

William Morris & Andy Warhol

MODERN ART EVENTS OXFORD THE YARD TOURS The Factory Floor Wednesday 7 January, 1pm Wednesday to Saturday, 12-5pm, weekly Sally Shaw, Head of Programme at Modern Art Oxford For the duration of Love is Enough, the Yard will discusses the development of the exhibition and be transformed into a ‘Factory Floor’ in homage to introduces key works. William Morris and Andy Warhol’s prolific production techniques. Each week a production method or craft Wednesday 21 January, 1pm skill will be demonstrated by a specialist. Ben Roberts, Curator of Education & Public Programmes at Modern Art Oxford discusses The Factory Floor is a rare opportunity to see creative education, collaboration and participation in relation to processes such as metal casting, dry stone walling, the work of Morris and Warhol. bookbinding, weaving and tapestry. LOVE IS Wednesday 4 February, 1pm These drop-in sessions provide a chance to meet Paul Teigh, Production Manager at Modern Art Oxford makers and craftspeople working with these processes discusses manufacturing and design processes today. Please see website for further details. inherent in the work of Morris and Warhol. TALKS Wednesday 18 February, 1pm Artist talk Ciara Moloney, Curator of Exhibitions & Projects Saturday 6 December, 6pm Free, booking essential at Modern Art Oxford discusses key works in the ENOUGH Jeremy Deller in conversation with Ralph Rugoff, exhibition and their influence on artistic practices Director, Hayward Gallery, London. today. Perspectives: Myth Thursday 15 January, 7pm BASEMENT: PERFORMANCE A series of short talks on myths and myth making from Live in the Studio the roots of medieval tales to our collective capacity December 2014 – February 2015 for fiction and how myths are made in contemporary A short series of performance projects working with culture. -

The Rise of Pop

Expos 20: The Rise of Pop Fall 2014 Barker 133, MW 10:00 & 11:00 Kevin Birmingham (birmingh@fas) Expos Office: 1 Bow Street #223 Office Hours: Mondays 12:15-2 The idea that there is a hierarchy of art forms – that some styles, genres and media are superior to others – extends at least as far back as Aristotle. Aesthetic categories have always been difficult to maintain, but they have been particularly fluid during the past fifty years in the United States. What does it mean to undercut the prestige of high art with popular culture? What happens to art and society when the boundaries separating high and low art are gone – when Proust and Porky Pig rub shoulders and the museum resembles the supermarket? This course examines fiction, painting and film during a roughly ten-year period (1964-1975) in which reigning cultural hierarchies disintegrated and older terms like “high culture” and “mass culture” began to lose their meaning. In the first unit, we will approach the death of the high art novel in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, which disrupts notions of literature through a superficial suburban American landscape and through the form of the novel itself. The second unit turns to Andy Warhol and Pop Art, which critics consider either an American avant-garde movement undermining high art or an unabashed celebration of vacuous consumer culture. In the third unit, we will turn our attention to The Rocky Horror Picture Show and the rise of cult films in the 1970s. Throughout the semester, we will engage art criticism, philosophy and sociology to help us make sense of important concepts that bear upon the status of art in modern society: tradition, craftsmanship, community, allusion, protest, authority and aura. -

Andy Warhol¬タルs Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography

OCAD University Open Research Repository Faculty of Liberal Arts & Sciences and School of Interdisciplinary Studies 2011 Andy Warhol’s Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography Charles Reeve OCAD University [email protected] © University of Hawai'i Press | Available at DOI: 10.1353/bio.2011.0066 Suggested citation: Reeve, Charles. “Andy Warhol’s Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography.” Biography 34.4 (2011): 657–675. Web. ANDY WARHOL’S DEATHS AND THE ASSEMBLY-LINE AUTOBIOGRAPHY CHARLES REEVE Test-driving the artworld cliché that dying young is the perfect career move, Andy Warhol starts his 1980 autobiography POPism: The Warhol Sixties by refl ecting, “If I’d gone ahead and died ten years ago, I’d probably be a cult fi gure today” (3). It’s vintage Warhol: off-hand, image-obsessed, and clever. It’s also, given Warhol’s preoccupation with fame, a lament. Sustaining one’s celebrity takes effort and nerves, and Warhol often felt incapable of either. “Oh, Archie, if you would only talk, I wouldn’t have to work another day in my life,” Bob Colacello, a key Warhol business functionary, recalls the art- ist whispering to one of his dachshunds: “Talk, Archie, talk” (144). Absent a talking dog, maybe cult status could relieve the pressure of fame, since it shoots celebrities into a timeless realm where their notoriety never fades. But cults only reach diehard fans, whereas Warhol’s posthumously pub- lished diaries emphasize that he coveted the stratospheric stardom of Eliza- beth Taylor and Michael Jackson—the fame that guaranteed mobs wherever they went. (Reviewing POPism in the New Yorker, Calvin Tomkins wrote that Warhol “pursued fame with the single-mindedness of a spawning salmon” [114].) Even more awkwardly, cult status entails dying—which means either you’re not around to enjoy your notoriety or, Warhol once nihilistically pro- posed, you’re not not around to enjoy it. -

Warhol, Recycling, Writing

From A to B and Back Again: Warhol, Recycling, Writing Christopher Schmidt I, too, dislike it—the impulse to claim Warhol as silent underwriter in virtually any aesthetic endeavor. Warhol invented reality television. Warhol would have loved YouTube. Jeff Koons is the heterosexual Warhol. It’s Warhol’s world; we just live in it. Is there a critical voice that does not have a claim on some aspect of the Warhol corpus, its bulk forever washing up on the shore of the contemporary? However much I suffer from Warhol fatigue, a quick perusal of The Philos- ophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again is sufficient to pull me back into the camp of Warhol boosters. I first discovered this 241-page little red book—the paperback is designed to look like a Campbell’s soup can—as a college student in the late 90s, when its sunny subversiveness and impatience with all things “intel- lectual” buoyed my spirits through the longueurs of New England winters. Warhol’s charm, the invention and breadth of his thought, thrilled me then and delights me still. The gap between my affection for the book and critical dismis- sal of it begs explanation and redress. Though overlooked as literature, The Philosophy is often mined by critics as a source for Warhol’s thought and personal history without due consideration given to the book’s form or its status as a transcribed, partially ghostwritten per- formance. Instead, Warhol’s aperçus are taken as uncomplicated truth: from Warhol’s brain to my dissertation. -

Pop Comes from the Outside: Warhol and Queer Childhood 78

c... o VI m. m '"...m »~ Z c:== ZI o N o U K E UN I V E R SIT Y PRE S S Durham and London 1996 Second printing, 1996 © 1996 Duke University Press All rights reserved ''I'll Be Your Mirror Stage: Andy Warhol and the Cultural Imaginary," © 1996 David E. James Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 00 Typeset in Berkeley Medium by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii JENNIFER DOYLE, JONATHAN FLATLEY, JOSE ESTEBAN MUNOZ Introduction 1 SIMON WATNEY Queer Andy 20 DAVID E. JAMES I'll Be Your Mirror Stage: Andy Warhol in the Cultural Imaginary 31 THOMAS WAUGH Cock teaser 51 MICHAEL MOON Screen Memories, or, Pop Comes from the Outside: Warhol and Queer Childhood 78 JONATHAN FLATLEY Warhol Gives Good Face: Publicity and the Politics of Prosopopoeia 101 EVE KOSOFSKY SEDGWICK Queer Performativity: Warhol's Shyness/Warhol's Whiteness 134 JOSE ESTEBAN MUNOZ Famous and Dandy Like B. 'n' Andy: Race, Pop, and Basquiat 144 vi Contents BRIAN SELSKY "I Dream of Genius, ,," 180 JENNIFER DOYLE Tricks of the Trade: Pop Art/Pop Sex 191 MARCIE FRANK Popping Off Warhol: From the Gutter to the Underground and Beyond 210 MANDY MERCK Figuring Out Andy Warhol 224 SASHA TORRES The Caped Crusader of Camp: Pop, Camp, and the Batman Television Series 238 Bibliography 257 Contributors 267 Index 269 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS his book was put together with the energy and excitement gener ated by a conference we organized at Duke University in January 1993 called "Re-Reading Warhol: The Politics of Pop." Our first thanks, then, go to the people who were instrumental in making that event happen, and especially to the people who participated in and attended the conference but did not contribute to this collection of essays. -

Part Two: Synaesthetic Cinema: the End of Drama

PART TWO: SYNAESTHETIC CINEMA: THE END OF DRAMA "The final poem will be the poem of fact in the language of fact. But it will be the poem of fact not realized before." WALLACE STEVENS Expanded cinema has been expanding for a long time. Since it left the underground and became a popular avant-garde form in the late 1950's the new cinema primarily has been an exercise in technique, the gradual development of a truly cinematic language with which to expand further man's communicative powers and thus his aware- ness. If expanded cinema has had anything to say, the message has been the medium.1 Slavko Vorkapich: "Most of the films made so far are examples not of creative use of motion-picture devices and techniques, but of their use as recording instruments only. There are extremely few motion pictures that may be cited as instances of creative use of the medium, and from these only fragments and short passages may be compared to the best achievements in the other arts."2 It has taken more than seventy years for global man to come to terms with the cinematic medium, to liberate it from theatre and literature. We had to wait until our consciousness caught up with our technology. But although the new cinema is the first and only true cinematic language, it still is used as a recording instrument. The recorded subject, however, is not the objective external human con- dition but the filmmaker's consciousness, his perception and its pro- 1 For a comprehensive in-depth history of this development, see: Sheldon Renan, An Introduction to the American Underground Film (New York: Dutton Paperbacks, 1967). -

The Films of Andy Warhol Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things

The Films of Andy Warhol Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things David Gariff National Gallery of Art If you wish for reputation and fame in the world . take every opportunity of advertising yourself. — Oscar Wilde In the future everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes. — attributed to Andy Warhol 1 The Films of Andy Warhol: Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things Andy Warhol’s interest and involvement in film ex- tends back to his childhood days in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Warhol was sickly and frail as a youngster. Illness often kept him bedridden for long periods of time, during which he read movie magazines and followed the lives of Hollywood celebri- ties. He was an avid moviegoer and amassed a large collection of publicity stills of stars given out by local theaters. He also created a movie scrapbook that included a studio portrait of Shirley Temple with the handwritten inscription: “To Andrew Worhola [sic] from Shirley Temple.” By the age of nine, Warhol had received his first camera. Warhol’s interests in cameras, movie projectors, films, the mystery of fame, and the allure of celebrity thus began in his formative years. Many labels attach themselves to Warhol’s work as a filmmaker: documentary, underground, conceptual, experi- mental, improvisational, sexploitation, to name only a few. His film and video output consists of approximately 650 films and 4,000 videos. He made most of his films in the five-year period from 1963 through 1968. These include Sleep (1963), a five- hour-and-twenty-one minute look at a man sleeping; Empire (1964), an eight-hour film of the Empire State Building; Outer and Inner Space (1965), starring Warhol’s muse Edie Sedgwick; and The Chelsea Girls (1966) (codirected by Paul Morrissey), a double-screen film that brought Warhol his greatest com- mercial distribution and success. -

Factory Girl Free Download

FACTORY GIRL FREE DOWNLOAD Pamela Oldfield | 160 pages | 03 Jan 2011 | Scholastic | 9781407116723 | English | London, United Kingdom Factory Girl (Rolling Stones song) Sign up here. The film is framed by Edie Sedgwick Sienna Miller being interviewed in a hospital several years after her time as an Andy Warhol superstar. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. We want to hear what you have to say but need to verify your account. Certified Fresh Picks. Beggars Banquet. Was this review helpful to you? Waiting Factory Girl a girl who's got curlers in her hair Waiting for Factory Girl girl, she has no money anywhere Factory Girl get buses everywhere, waiting for a factory girl. Micheal Compton. Andy Warhol dove into most things artistic; shaping Pop Art, producing The Velvet Underground, and making his own films. Namespaces Article Talk. In Factory Girl, a jumbled account of the short life and photogenic hard times of the first Andy Warhol superstar, Edie Sedgwick, Sienna Miller makes Sedgwick into an archetypal over-confident blond with a mannered young Kathleen Turner croak. Best Horror Movies. Add Article. Andy Warhol: You're the boss, applesauce! By the end of the film, I didn't think I learned anything true. We want to hear what you have to say but need to verify your email. Log in here. June 15, Clear your history. Sienna Miller defended the film against Dylan's allegations, saying in an interview with the Guardian, Factory Girl blames Warhol more than anyone, because he did abandon her Regal Coming Soon.