Moma Andy Warhol Motion Pictures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andy Warhol's

13 MOST BEAUTIFUL... SONGS FOR ANDY WARHOL’S SCREEN TESTS FEAUTURING DEAN & BRITTA JANUARY 17, 2015 OZ ARTS NASHVILLE SUPPORTS THE CREATION, DEVELOPMENT AND PRESENTATION OF SIGNIFICANT CONTEMPORARY PERFORMING AND VISUAL ART WORKS BY LEADING ARTISTS WHOSE CONTRIBUTION INFLUENCES THE ADVANCEMENT OF THEIR FIELD. ADVISORY BOARD Amy Atkinson Karen Elson Jill Robinson Anne Brown Karen Hayes Patterson Sims Libby Callaway Gavin Ivester Mike Smith Chase Cole Keith Meacham Ronnie Steine Jen Cole Ellen Meyer Joseph Sulkowski Stephanie Conner Dave Pittman Stacy Widelitz Gavin Duke Paul Polycarpou Betsy Wills Kristy Edmunds Anne Pope Mel Ziegler aA MESSAGE FROM OZ ARTS President John F. Kennedy had just been assassinated, the Civil Rights Act was mere months from inception, and the US was becoming more heavily involved in the conflict in Vietnam. It was 1964, and at The Factory in New York, Andy Warhol was experimenting with film. Over the course of two years, Andy Warhol selected regulars to his factory, both famous and anonymous that he felt had “star potential” to sit and be filmed in one take, using 100 foot rolls of film. It has been documented that Warhol shot nearly 500 screen tests, but not all were kept. Many of his screen tests have been curated into groups that start with “13 Most Beautiful…” To accompany these film portraits, Dean & Britta, formerly of the NY band, Luna, were commissioned by the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust and The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to create original songs, and remixes of songs from musicians of the era. This endeavor led Dean & Britta to a third studio album consisting of a total of 21 songs titled, “13 Most Beautiful.. -

NO RAMBLING ON: the LISTLESS COWBOYS of HORSE Jon Davies

WARHOL pages_BFI 25/06/2013 10:57 Page 108 If Andy Warhol’s queer cinema of the 1960s allowed for a flourishing of newly articulated sexual and gender possibilities, it also fostered a performative dichotomy: those who command the voice and those who do not. Many of his sound films stage a dynamic of stoicism and loquaciousness that produces a complex and compelling web of power and desire. The artist has summed the binary up succinctly: ‘Talk ers are doing something. Beaut ies are being something’ 1 and, as Viva explained about this tendency in reference to Warhol’s 1968 Lonesome Cowboys : ‘Men seem to have trouble doing these nonscript things. It’s a natural 5_ 10 2 for women and fags – they ramble on. But straight men can’t.’ The brilliant writer and progenitor of the Theatre of the Ridiculous Ronald Tavel’s first two films as scenarist for Warhol are paradigmatic in this regard: Screen Test #1 and Screen Test #2 (both 1965). In Screen Test #1 , the performer, Warhol’s then lover Philip Fagan, is completely closed off to Tavel’s attempts at spurring him to act out and to reveal himself. 3 According to Tavel, he was so up-tight. He just crawled into himself, and the more I asked him, the more up-tight he became and less was recorded on film, and, so, I got more personal about touchy things, which became the principle for me for the next six months. 4 When Tavel turned his self-described ‘sadism’ on a true cinematic superstar, however, in Screen Test #2 , the results were extraordinary. -

Warhol, Andy (As Filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol

Warhol, Andy (as filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol. by David Ehrenstein Image appears under the Creative Commons Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy Jack Mitchell. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com As a painter Andy Warhol (the name he assumed after moving to New York as a young man) has been compared to everyone from Salvador Dalí to Norman Rockwell. But when it comes to his role as a filmmaker he is generally remembered either for a single film--Sleep (1963)--or for works that he did not actually direct. Born into a blue-collar family in Forest City, Pennsylvania on August 6, 1928, Andrew Warhola, Jr. attended art school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. He moved to New York in 1949, where he changed his name to Andy Warhol and became an international icon of Pop Art. Between 1963 and 1967 Warhol turned out a dizzying number and variety of films involving many different collaborators, but after a 1968 attempt on his life, he retired from active duty behind the camera, becoming a producer/ "presenter" of films, almost all of which were written and directed by Paul Morrissey. Morrissey's Flesh (1968), Trash (1970), and Heat (1972) are estimable works. And Bad (1977), the sole opus of Warhol's lover Jed Johnson, is not bad either. But none of these films can compare to the Warhol films that preceded them, particularly My Hustler (1965), an unprecedented slice of urban gay life; Beauty #2 (1965), the best of the films featuring Edie Sedgwick; The Chelsea Girls (1966), the only experimental film to gain widespread theatrical release; and **** (Four Stars) (1967), the 25-hour long culmination of Warhol's career as a filmmaker. -

Exhibiting Warhols's Screen Tests

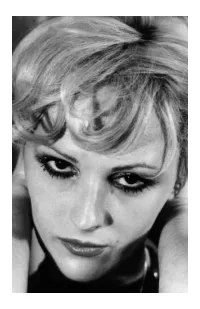

1 EXHIBITING WARHOL’S SCREEN TESTS Ian Walker The work of Andy Warhol seems nighwell ubiquitous now, and its continuing relevance and pivotal position in recent culture remains indisputable. Towards the end of 2014, Warhol’s work could be found in two very different shows in Britain. Tate Liverpool staged Transmitting Andy Warhol, which, through a mix of paintings, films, drawings, prints and photographs, sought to explore ‘Warhol’s role in establishing new processes for the dissemination of art’.1 While, at Modern Art Oxford, Jeremy Deller curated the exhibition Love is Enough, bringing together the work of William Morris and Andy Warhol to idiosyncratic but striking effect.2 On a less grand scale was the screening, also at Modern Art Oxford over the week of December 2-7, of a programme of Warhol’s Screen Tests. They were shown in the ‘Project Space’ as part of a programme entitled Straight to Camera: Performance for Film.3 As the title suggests, this featured work by a number of artists in which a performance was directly addressed to the camera and recorded in unrelenting detail. The Screen Tests which Warhol shot in 1964-66 were the earliest works in the programme and stood, as it were, as a starting point for this way of working. Fig 1: Cover of Callie Angell, Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests, 2006 2 How they were made is by now the stuff of legend. A 16mm Bolex camera was set up in a corner of the Factory and the portraits made as the participants dropped by or were invited to sit. -

The Rise of Pop

Expos 20: The Rise of Pop Fall 2014 Barker 133, MW 10:00 & 11:00 Kevin Birmingham (birmingh@fas) Expos Office: 1 Bow Street #223 Office Hours: Mondays 12:15-2 The idea that there is a hierarchy of art forms – that some styles, genres and media are superior to others – extends at least as far back as Aristotle. Aesthetic categories have always been difficult to maintain, but they have been particularly fluid during the past fifty years in the United States. What does it mean to undercut the prestige of high art with popular culture? What happens to art and society when the boundaries separating high and low art are gone – when Proust and Porky Pig rub shoulders and the museum resembles the supermarket? This course examines fiction, painting and film during a roughly ten-year period (1964-1975) in which reigning cultural hierarchies disintegrated and older terms like “high culture” and “mass culture” began to lose their meaning. In the first unit, we will approach the death of the high art novel in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, which disrupts notions of literature through a superficial suburban American landscape and through the form of the novel itself. The second unit turns to Andy Warhol and Pop Art, which critics consider either an American avant-garde movement undermining high art or an unabashed celebration of vacuous consumer culture. In the third unit, we will turn our attention to The Rocky Horror Picture Show and the rise of cult films in the 1970s. Throughout the semester, we will engage art criticism, philosophy and sociology to help us make sense of important concepts that bear upon the status of art in modern society: tradition, craftsmanship, community, allusion, protest, authority and aura. -

Research Article

Research Article Embodied Curation: Materials, Performance and the Generation of Knowledge Andy Ditzler* Founder and Curator, Film Love Sydney M. Silverstein Department of Anthropology, Emory University *[email protected] Visual Methodologies: http://journals.sfu.ca/vm/index.php/vm/index Visual Methodologies, Volume 4, Number 1, pp.52-63. Ditzler and Silverstein Research Article The following essay unfolds as a conversation about the staging of a cinematographic tribute to Lou Reed and to the Velvet Underground’s early involvement with Andy Warhol and with underground cinema. The conversation—between the curator-host and an anthropologist-filmmaker present in the audience—pieces together personal registers of the event to make a case for embodied curation—a series of trans-disciplinary and multisensory research and performance practices that are generative of new ways of knowing about, and through, historical materials. Rather than a didactic endeavor, the encounters between curator, materials, and audience members generated new forms of embodied knowledge. Making a case for embodied methods of research and performance, we argue that this generation of knowledge was made possible only through the particular constellation of materials and practices that came together in the staging of this event. Keywords: Andy Warhol, Embodied Curation, Film Projection, Mechanical ABSTRACT Reproduction, Sensory Scholarship, Visual Methodologies. ISSN: 2040-5456 Copyright © 2016 The Research Methods Laboratory. 53 The equipment-free aspect of reality here has become the height of artifice; the sight of immediate reality has become an orchid in the land of technology. -Walter Benjamin “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”(1967: 233) Figure 1: Curator and projections, Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, February 21, 2014. -

Andy Warhol¬タルs Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography

OCAD University Open Research Repository Faculty of Liberal Arts & Sciences and School of Interdisciplinary Studies 2011 Andy Warhol’s Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography Charles Reeve OCAD University [email protected] © University of Hawai'i Press | Available at DOI: 10.1353/bio.2011.0066 Suggested citation: Reeve, Charles. “Andy Warhol’s Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography.” Biography 34.4 (2011): 657–675. Web. ANDY WARHOL’S DEATHS AND THE ASSEMBLY-LINE AUTOBIOGRAPHY CHARLES REEVE Test-driving the artworld cliché that dying young is the perfect career move, Andy Warhol starts his 1980 autobiography POPism: The Warhol Sixties by refl ecting, “If I’d gone ahead and died ten years ago, I’d probably be a cult fi gure today” (3). It’s vintage Warhol: off-hand, image-obsessed, and clever. It’s also, given Warhol’s preoccupation with fame, a lament. Sustaining one’s celebrity takes effort and nerves, and Warhol often felt incapable of either. “Oh, Archie, if you would only talk, I wouldn’t have to work another day in my life,” Bob Colacello, a key Warhol business functionary, recalls the art- ist whispering to one of his dachshunds: “Talk, Archie, talk” (144). Absent a talking dog, maybe cult status could relieve the pressure of fame, since it shoots celebrities into a timeless realm where their notoriety never fades. But cults only reach diehard fans, whereas Warhol’s posthumously pub- lished diaries emphasize that he coveted the stratospheric stardom of Eliza- beth Taylor and Michael Jackson—the fame that guaranteed mobs wherever they went. (Reviewing POPism in the New Yorker, Calvin Tomkins wrote that Warhol “pursued fame with the single-mindedness of a spawning salmon” [114].) Even more awkwardly, cult status entails dying—which means either you’re not around to enjoy your notoriety or, Warhol once nihilistically pro- posed, you’re not not around to enjoy it. -

Warhol, Recycling, Writing

From A to B and Back Again: Warhol, Recycling, Writing Christopher Schmidt I, too, dislike it—the impulse to claim Warhol as silent underwriter in virtually any aesthetic endeavor. Warhol invented reality television. Warhol would have loved YouTube. Jeff Koons is the heterosexual Warhol. It’s Warhol’s world; we just live in it. Is there a critical voice that does not have a claim on some aspect of the Warhol corpus, its bulk forever washing up on the shore of the contemporary? However much I suffer from Warhol fatigue, a quick perusal of The Philos- ophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again is sufficient to pull me back into the camp of Warhol boosters. I first discovered this 241-page little red book—the paperback is designed to look like a Campbell’s soup can—as a college student in the late 90s, when its sunny subversiveness and impatience with all things “intel- lectual” buoyed my spirits through the longueurs of New England winters. Warhol’s charm, the invention and breadth of his thought, thrilled me then and delights me still. The gap between my affection for the book and critical dismis- sal of it begs explanation and redress. Though overlooked as literature, The Philosophy is often mined by critics as a source for Warhol’s thought and personal history without due consideration given to the book’s form or its status as a transcribed, partially ghostwritten per- formance. Instead, Warhol’s aperçus are taken as uncomplicated truth: from Warhol’s brain to my dissertation. -

Part Two: Synaesthetic Cinema: the End of Drama

PART TWO: SYNAESTHETIC CINEMA: THE END OF DRAMA "The final poem will be the poem of fact in the language of fact. But it will be the poem of fact not realized before." WALLACE STEVENS Expanded cinema has been expanding for a long time. Since it left the underground and became a popular avant-garde form in the late 1950's the new cinema primarily has been an exercise in technique, the gradual development of a truly cinematic language with which to expand further man's communicative powers and thus his aware- ness. If expanded cinema has had anything to say, the message has been the medium.1 Slavko Vorkapich: "Most of the films made so far are examples not of creative use of motion-picture devices and techniques, but of their use as recording instruments only. There are extremely few motion pictures that may be cited as instances of creative use of the medium, and from these only fragments and short passages may be compared to the best achievements in the other arts."2 It has taken more than seventy years for global man to come to terms with the cinematic medium, to liberate it from theatre and literature. We had to wait until our consciousness caught up with our technology. But although the new cinema is the first and only true cinematic language, it still is used as a recording instrument. The recorded subject, however, is not the objective external human con- dition but the filmmaker's consciousness, his perception and its pro- 1 For a comprehensive in-depth history of this development, see: Sheldon Renan, An Introduction to the American Underground Film (New York: Dutton Paperbacks, 1967). -

The Films of Andy Warhol Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things

The Films of Andy Warhol Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things David Gariff National Gallery of Art If you wish for reputation and fame in the world . take every opportunity of advertising yourself. — Oscar Wilde In the future everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes. — attributed to Andy Warhol 1 The Films of Andy Warhol: Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things Andy Warhol’s interest and involvement in film ex- tends back to his childhood days in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Warhol was sickly and frail as a youngster. Illness often kept him bedridden for long periods of time, during which he read movie magazines and followed the lives of Hollywood celebri- ties. He was an avid moviegoer and amassed a large collection of publicity stills of stars given out by local theaters. He also created a movie scrapbook that included a studio portrait of Shirley Temple with the handwritten inscription: “To Andrew Worhola [sic] from Shirley Temple.” By the age of nine, Warhol had received his first camera. Warhol’s interests in cameras, movie projectors, films, the mystery of fame, and the allure of celebrity thus began in his formative years. Many labels attach themselves to Warhol’s work as a filmmaker: documentary, underground, conceptual, experi- mental, improvisational, sexploitation, to name only a few. His film and video output consists of approximately 650 films and 4,000 videos. He made most of his films in the five-year period from 1963 through 1968. These include Sleep (1963), a five- hour-and-twenty-one minute look at a man sleeping; Empire (1964), an eight-hour film of the Empire State Building; Outer and Inner Space (1965), starring Warhol’s muse Edie Sedgwick; and The Chelsea Girls (1966) (codirected by Paul Morrissey), a double-screen film that brought Warhol his greatest com- mercial distribution and success. -

September 19 Skype Chat in Dialogue Thierry Frémaux: Lumière! 1895

October 3 In person In Dialogue Virginia Heffernan: Magic and Loss, The Internet as Art Sponsor: Norwich Bookstore, Simon and Schuster Author, journalist and cultural critic (New York Times, Los Angeles Times), Virginia Heffernan sees the Internet as “the greatest masterpiece of human civilization,” steadily transforming all sensory and emotional experiences. Join us for a stimulating encounter with America’s most playful and engaging non-commentator commentator. Book signing follows talk. Devices welcome! October 10 In person Location: Rm 001, Black Family Visual Arts Center, Dartmouth College Audio-Vision Sources for 2001: A Space Odyssey Sponsors: Dartmouth’s Department of Music, Film and Media Studies Ciné Salon Fall 2016 celebrates 20 years of rare and classic Media artist Carlos Casa explores inspirations for director Stanley experiments in film introduced and discussed by some of the Kubrick’s 2001 with primary attention paid to the National Film world’s foremost authorities on media arts. More than 600 films Board of Canada documentary Universe, several visual music have screened in 269 thematic programs that have highlighted milestones, and Gyorgy Ligeti’s ethereal music compositions. genuinely engaging, often-difficult films and related subjects. FILMS: Universe (1960) Roman Kroitor, Colin Low; 28 min; Catalog (1961) John Whitney 8 min; Re-Entry (1963) Jordan Belson 6 min; audio only Atmosphères The anniversary emphasizes our commitment to keep alive the (1961) Gyorgy Ligeti 9 min. past, present and future of a vital art forum -

Make Pop Art Like Warhol

MAKE POP ART LIKE WARHOL Design your own piece of pop art inspired by this famous artist WHO IS ANDY WARHOL? Andy Warhol is one of the most famous artists, ever. From his soup to his hair, he is an art legend. Andy Warhol was part of the pop art movement. He was born Andrew Warhola in 1928 in Pennsylvania. His parents were from a part of Europe that is now part of Slovakia. They moved to New York in the 1920s. His first job was illustrating adverts in fashion magazines. Now is he known as one of the most influential artists who ever lived! Warhol was gay and expressed his identity through his life and art. During his lifetime being gay was illegal in the United States. WHAT IS HE FAMOUS FOR? He is famous for exploring popular culture in his work. Popular culture is anything from Coca Cola to pop stars to the clothes people like to wear. He made a print of Campbell’s Soup – a popular brand of soup in the United States. He said he ate Campbell’s tomato soup every day for lunch for 20 years! In the 1960s Andy Warhol became known as one of the leading artists of the pop art movement. WHAT IS POP ART? Pop artists felt that art should reflect modern life and so they made art inspired by the world around them – from movies, advertising and pop music to comic books and even product packaging. Find out more in this short film ……. https://www.tate.org.uk/kids/explore/who-is/who-andy-warhol Warhol was famous for exploring everyday and familiar objects in his work, using brands such as Coca- Cola, Brillo and Campbell’s Soup.