On Andy Warhol's Electric Chair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Our Full Report, Death in Florida, Now

USA DEATH IN FLORIDA GOVERNOR REMOVES PROSECUTOR FOR NOT SEEKING DEATH SENTENCES; FIRST EXECUTION IN 18 MONTHS LOOMS Amnesty International Publications First published on 21 August 2017 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2017 Index: AMR 51/6736/2017 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 3 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations Table of Contents Summary ..................................................................................................................... 1 ‘Bold, positive change’ not allowed ................................................................................ -

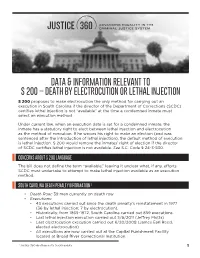

Death by Electrocution Or Lethal Injection

DATA & INFORMATION RELEVANT TO S 200 – DEATH BY ELECTROCUTION OR LETHAL INJECTION S 200 proposes to make electrocution the only method for carrying out an execution in South Carolina if the director of the Department of Corrections (SCDC) certifies lethal injection is not “available” at the time a condemned inmate must select an execution method. Under current law, when an execution date is set for a condemned inmate, the inmate has a statutory right to elect between lethal injection and electrocution as the method of execution. If he waives his right to make an election (and was sentenced after the introduction of lethal injection), the default method of execution is lethal injection. S 200 would remove the inmates’ right of election if the director of SCDC certifies lethal injection is not available. See S.C. Code § 24-3-530. CONCERNS ABOUT S 200 LANGUAGE The bill does not define the term “available,” leaving it unclear what, if any, efforts SCDC must undertake to attempt to make lethal injection available as an execution method. SOUTH CAROLINA DEATH PENALTY INFORMATION 1 • Death Row: 39 men currently on death row • Executions: • 43 executions carried out since the death penalty’s reinstatement in 1977 (36 by lethal injection; 7 by electrocution). • Historically, from 1865–1972, South Carolina carried out 859 executions. • Last lethal injection execution carried out 5/6/2011 (Jeffrey Motts) • Last electrocution execution carried out 6/20/2008 (James Earl Reed, elected electrocution) • All executions are now carried out at the Capital Punishment Facility located at Broad River Correctional Institution. 1 Justice 360 death penalty tracking data. -

Moma Andy Warhol Motion Pictures

MoMA PRESENTS ANDY WARHOL’S INFLUENTIAL EARLY FILM-BASED WORKS ON A LARGE SCALE IN BOTH A GALLERY AND A CINEMATIC SETTING Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures December 19, 2010–March 21, 2011 The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art Gallery, sixth floor Press Preview: Tuesday, December 14, 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. Remarks at 11:00 a.m. Click here or call (212) 708-9431 to RSVP NEW YORK, December 8, 2010—Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures, on view at MoMA from December 19, 2010, to March 21, 2011, focuses on the artist's cinematic portraits and non- narrative, silent, and black-and-white films from the mid-1960s. Warhol’s Screen Tests reveal his lifelong fascination with the cult of celebrity, comprising a visual almanac of the 1960s downtown avant-garde scene. Included in the exhibition are such Warhol ―Superstars‖ as Edie Sedgwick, Nico, and Baby Jane Holzer; poet Allen Ginsberg; musician Lou Reed; actor Dennis Hopper; author Susan Sontag; and collector Ethel Scull, among others. Other early films included in the exhibition are Sleep (1963), Eat (1963), Blow Job (1963), and Kiss (1963–64). Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures is organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Chief Curator at Large, The Museum of Modern Art, and Director, MoMA PS1. This exhibition is organized in collaboration with The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Twelve Screen Tests in this exhibition are projected on the gallery walls at large scale and within frames, some measuring seven feet high and nearly nine feet wide. An excerpt of Sleep is shown as a large-scale projection at the entrance to the exhibition, with Eat and Blow Job shown on either side of that projection; Kiss is shown at the rear of the gallery in a 50-seat movie theater created for the exhibition; and Sleep and Empire (1964), in their full durations, will be shown in this theater at specially announced times. -

UNITED STATES of AMERICA the Execution of Mentally Ill Offenders

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA The execution of mentally ill offenders I cannot believe that capital punishment is a solution – to abolish murder by murdering, an endless chain of murdering. When I heard that my daughter’s murderer was not to be executed, my first reaction was immense relief from an additional torment: the usual catastrophe, breeding more catastrophe, was to be stopped – it might be possible to turn the bad into good. I felt with this man, the victim of a terrible sickness, of a demon over which he had no control, might even help to establish the reasons that caused his insanity and to find a cure for it... Mother of 19-year-old murder victim, California, November 1960(1) Today, at 6pm, the State of Florida is scheduled to kill my brother, Thomas Provenzano, despite clear evidence that he is mentally ill.... I have to wonder: Where is the justice in killing a sick human being? Sister of death row inmate, June 2000(2) I’ve got one thing to say, get your Warden off this gurney and shut up. I am from the island of Barbados. I am the Warden of this unit. People are seeing you do this. Final statement of Monty Delk, mentally ill man executed in Texas on 28 February 2002 Overview: A gap in the ‘evolving standards of decency’ The underlying rationale for prohibiting executions of the mentally retarded is just as compelling for prohibiting executions of the seriously mentally ill, namely evolving standards of decency. Indiana Supreme Court Justice, September 2002(3) On 30 May 2002, a jury in Maryland sentenced Francis Zito to death. -

Warhol, Andy (As Filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol

Warhol, Andy (as filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol. by David Ehrenstein Image appears under the Creative Commons Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy Jack Mitchell. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com As a painter Andy Warhol (the name he assumed after moving to New York as a young man) has been compared to everyone from Salvador Dalí to Norman Rockwell. But when it comes to his role as a filmmaker he is generally remembered either for a single film--Sleep (1963)--or for works that he did not actually direct. Born into a blue-collar family in Forest City, Pennsylvania on August 6, 1928, Andrew Warhola, Jr. attended art school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. He moved to New York in 1949, where he changed his name to Andy Warhol and became an international icon of Pop Art. Between 1963 and 1967 Warhol turned out a dizzying number and variety of films involving many different collaborators, but after a 1968 attempt on his life, he retired from active duty behind the camera, becoming a producer/ "presenter" of films, almost all of which were written and directed by Paul Morrissey. Morrissey's Flesh (1968), Trash (1970), and Heat (1972) are estimable works. And Bad (1977), the sole opus of Warhol's lover Jed Johnson, is not bad either. But none of these films can compare to the Warhol films that preceded them, particularly My Hustler (1965), an unprecedented slice of urban gay life; Beauty #2 (1965), the best of the films featuring Edie Sedgwick; The Chelsea Girls (1966), the only experimental film to gain widespread theatrical release; and **** (Four Stars) (1967), the 25-hour long culmination of Warhol's career as a filmmaker. -

The Rise of Pop

Expos 20: The Rise of Pop Fall 2014 Barker 133, MW 10:00 & 11:00 Kevin Birmingham (birmingh@fas) Expos Office: 1 Bow Street #223 Office Hours: Mondays 12:15-2 The idea that there is a hierarchy of art forms – that some styles, genres and media are superior to others – extends at least as far back as Aristotle. Aesthetic categories have always been difficult to maintain, but they have been particularly fluid during the past fifty years in the United States. What does it mean to undercut the prestige of high art with popular culture? What happens to art and society when the boundaries separating high and low art are gone – when Proust and Porky Pig rub shoulders and the museum resembles the supermarket? This course examines fiction, painting and film during a roughly ten-year period (1964-1975) in which reigning cultural hierarchies disintegrated and older terms like “high culture” and “mass culture” began to lose their meaning. In the first unit, we will approach the death of the high art novel in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, which disrupts notions of literature through a superficial suburban American landscape and through the form of the novel itself. The second unit turns to Andy Warhol and Pop Art, which critics consider either an American avant-garde movement undermining high art or an unabashed celebration of vacuous consumer culture. In the third unit, we will turn our attention to The Rocky Horror Picture Show and the rise of cult films in the 1970s. Throughout the semester, we will engage art criticism, philosophy and sociology to help us make sense of important concepts that bear upon the status of art in modern society: tradition, craftsmanship, community, allusion, protest, authority and aura. -

Masquerade, Crime and Fiction

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and over- worked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discern- ing readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true- crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Published titles include: Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Ed Christian (editor) THE POST-COLONIAL DETECTIVE Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Lee Horsley THE NOIR THRILLER Fran Mason AMERICAN GANGSTER CINEMA From Little Caesar to Pulp Fiction Linden Peach MASQUERADE, CRIME AND FICTION Criminal Deceptions Susan Rowland FROM AGATHA CHRISTIE TO RUTH RENDELL British Women Writers in Detective and Crime Fiction Adrian Schober POSSESSED CHILD NARRATIVES IN LITERATURE AND FILM Contrary States Heather Worthington THE RISE OF THE DETECTIVE IN EARLY NINETEENTH-CENTURY POPULAR FICTION Crime Files Series Standing Order ISBN 978-0–333–71471–3 (Hardback) 978-0–333–93064–9 (Paperback) (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. -

Andy Warhol: When Junkies Ruled the World

Nebula 2.2 , June 2005 Andy Warhol: When Junkies Ruled the World. By Michael Angelo Tata So when the doorbell rang the night before, it was Liza in a hat pulled down so nobody would recognize her, and she said to Halston, “Give me every drug you’ve got.” So he gave her a bottle of coke, a few sticks of marijuana, a Valium, four Quaaludes, and they were all wrapped in a tiny box, and then a little figure in a white hat came up on the stoop and kissed Halston, and it was Marty Scorsese, he’d been hiding around the corner, and then he and Liza went off to have their affair on all the drugs ( Diaries , Tuesday, January 3, 1978). Privileged Intake Of all the creatures who populate and punctuate Warhol’s worlds—drag queens, hustlers, movie stars, First Wives—the drug user and abuser retains a particular access to glamour. Existing along a continuum ranging from the occasional substance dilettante to the hard-core, raging junkie, the consumer of drugs preoccupies Warhol throughout the 60s, 70s and 80s. Their actions and habits fascinate him, his screens become the sacred place where their rituals are projected and packaged. While individual substance abusers fade from the limelight, as in the disappearance of Ondine shortly after the commercial success of The Chelsea Girls , the loss of status suffered by Brigid Polk in the 70s and 80s, or the fatal overdose of exemplary drug fiend Edie Sedgwick, the actual glamour of drugs remains, never giving up its allure. 1 Drugs survive the druggie, who exists merely as a vector for the 1 While Brigid Berlin continues to exert a crucial influence on Warhol’s work in the 70s and 80s—for example, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol , as detailed by Bob Colacello in the chapter “Paris (and Philosophy )”—her street cred. -

Execution Ritual : Media Representations of Execution and the Social Construction of Public Opinion Regarding the Death Penalty

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2011 Execution ritual : media representations of execution and the social construction of public opinion regarding the death penalty. Emilie Dyer 1987- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Dyer, Emilie 1987-, "Execution ritual : media representations of execution and the social construction of public opinion regarding the death penalty." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 388. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/388 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXECUTION RITUAL: MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF EXECUTION AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC OPINION REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY By Emilie Dyer B.A., University of Louisville, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fullfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May, 2011 -------------------------------------------------------------- EXECUTION RITUAL : MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF EXECUTION AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC OPINION REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY By Emilie Brook Dyer B.A., University of Louisville, 2009 A Thesis Approved on April 11, 2011 by the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director (Dr. -

California State University, Northridge Exploitation

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE EXPLOITATION, WOMEN AND WARHOL A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art by Kathleen Frances Burke May 1986 The Thesis of Kathleen Frances Burke is approved: Louise Leyis, M.A. Dianne E. Irwin, Ph.D. r<Iary/ Kenan Ph.D. , Chair California State. University, Northridge ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Dr. Mary Kenon Breazeale, whose tireless efforts have brought it to fruition. She taught me to "see" and interpret art history in a different way, as a feminist, proving that women's perspectives need not always agree with more traditional views. In addition, I've learned that personal politics does not have to be sacrificed, or compartmentalized in my life, but that it can be joined with a professional career and scholarly discipline. My time as a graduate student with Dr. Breazeale has had a profound effect on my personal life and career, and will continue to do so whatever paths my life travels. For this I will always be grateful. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In addition, I would like to acknowledge the other members of my committee: Louise Lewis and Dr. Dianne Irwin. They provided extensive editorial comments which helped me to express my ideas more clearly and succinctly. I would like to thank the six branches of the Glendale iii Public Library and their staffs, in particular: Virginia Barbieri, Claire Crandall, Fleur Osmanson, Nora Goldsmith, Cynthia Carr and Joseph Fuchs. They provided me with materials and research assistance for this project. I would also like to thank the members of my family. -

Andy Warhol¬タルs Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography

OCAD University Open Research Repository Faculty of Liberal Arts & Sciences and School of Interdisciplinary Studies 2011 Andy Warhol’s Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography Charles Reeve OCAD University [email protected] © University of Hawai'i Press | Available at DOI: 10.1353/bio.2011.0066 Suggested citation: Reeve, Charles. “Andy Warhol’s Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography.” Biography 34.4 (2011): 657–675. Web. ANDY WARHOL’S DEATHS AND THE ASSEMBLY-LINE AUTOBIOGRAPHY CHARLES REEVE Test-driving the artworld cliché that dying young is the perfect career move, Andy Warhol starts his 1980 autobiography POPism: The Warhol Sixties by refl ecting, “If I’d gone ahead and died ten years ago, I’d probably be a cult fi gure today” (3). It’s vintage Warhol: off-hand, image-obsessed, and clever. It’s also, given Warhol’s preoccupation with fame, a lament. Sustaining one’s celebrity takes effort and nerves, and Warhol often felt incapable of either. “Oh, Archie, if you would only talk, I wouldn’t have to work another day in my life,” Bob Colacello, a key Warhol business functionary, recalls the art- ist whispering to one of his dachshunds: “Talk, Archie, talk” (144). Absent a talking dog, maybe cult status could relieve the pressure of fame, since it shoots celebrities into a timeless realm where their notoriety never fades. But cults only reach diehard fans, whereas Warhol’s posthumously pub- lished diaries emphasize that he coveted the stratospheric stardom of Eliza- beth Taylor and Michael Jackson—the fame that guaranteed mobs wherever they went. (Reviewing POPism in the New Yorker, Calvin Tomkins wrote that Warhol “pursued fame with the single-mindedness of a spawning salmon” [114].) Even more awkwardly, cult status entails dying—which means either you’re not around to enjoy your notoriety or, Warhol once nihilistically pro- posed, you’re not not around to enjoy it. -

ACTING out Rowan University Art Gallery January 20 – March 12, 2011

ACTING OUT Rowan University Art Gallery January 20 – March 12, 2011 Nina Katchadourian Fahamu Pecou Nancy Popp Shana Robbins ACTING JoeOUT Sola Jaimie Warren Curated by Stuart Horodner A child is told that he or she cannot have a slice of cake and Nina Katchadourian’s discipline-bending work is investigative, then proceeds to scream and cry for several minutes. playful, and precise. She is as comfortable in a library This is a disproportionate response, and acting out conduct sorting books to find latent meanings in their titles as is understood to operate in the gap between desire and she is in rewiring automobiles to emit alarm sounds in disappointment. The words acting and out combine to the form of bird calls. In the passport-sized photograph, imply public displays and testing of wills, with young- Self-Portrait as Sir Ernest Shackleton (2002), she attaches two cat- sters flailing about or holding their breath until an au- erpillars to her upper lip and dons a fluffy white sweater thority figure asserts that “No means no,” and a “time and cap to play with gender while honoring an intrepid explorer. out” is required. Troubled protagonists are sent to their rooms Her video, Mystic Shark (2007), was shot in a hotel room to consider their unacceptable behavior. in Connecticut, and shows the artist holding up a blue book with a line drawing of a shark on it, telegraphing When artists are faced with frustrations over unmet her intention to become like this predatory creature. She wants, their outbursts usually take the form of renewed then proceeds to earnestly try and outfit her mouth with several dedication and persistent production.