Research Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moma Andy Warhol Motion Pictures

MoMA PRESENTS ANDY WARHOL’S INFLUENTIAL EARLY FILM-BASED WORKS ON A LARGE SCALE IN BOTH A GALLERY AND A CINEMATIC SETTING Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures December 19, 2010–March 21, 2011 The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art Gallery, sixth floor Press Preview: Tuesday, December 14, 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. Remarks at 11:00 a.m. Click here or call (212) 708-9431 to RSVP NEW YORK, December 8, 2010—Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures, on view at MoMA from December 19, 2010, to March 21, 2011, focuses on the artist's cinematic portraits and non- narrative, silent, and black-and-white films from the mid-1960s. Warhol’s Screen Tests reveal his lifelong fascination with the cult of celebrity, comprising a visual almanac of the 1960s downtown avant-garde scene. Included in the exhibition are such Warhol ―Superstars‖ as Edie Sedgwick, Nico, and Baby Jane Holzer; poet Allen Ginsberg; musician Lou Reed; actor Dennis Hopper; author Susan Sontag; and collector Ethel Scull, among others. Other early films included in the exhibition are Sleep (1963), Eat (1963), Blow Job (1963), and Kiss (1963–64). Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures is organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Chief Curator at Large, The Museum of Modern Art, and Director, MoMA PS1. This exhibition is organized in collaboration with The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Twelve Screen Tests in this exhibition are projected on the gallery walls at large scale and within frames, some measuring seven feet high and nearly nine feet wide. An excerpt of Sleep is shown as a large-scale projection at the entrance to the exhibition, with Eat and Blow Job shown on either side of that projection; Kiss is shown at the rear of the gallery in a 50-seat movie theater created for the exhibition; and Sleep and Empire (1964), in their full durations, will be shown in this theater at specially announced times. -

Andy Warhol's

13 MOST BEAUTIFUL... SONGS FOR ANDY WARHOL’S SCREEN TESTS FEAUTURING DEAN & BRITTA JANUARY 17, 2015 OZ ARTS NASHVILLE SUPPORTS THE CREATION, DEVELOPMENT AND PRESENTATION OF SIGNIFICANT CONTEMPORARY PERFORMING AND VISUAL ART WORKS BY LEADING ARTISTS WHOSE CONTRIBUTION INFLUENCES THE ADVANCEMENT OF THEIR FIELD. ADVISORY BOARD Amy Atkinson Karen Elson Jill Robinson Anne Brown Karen Hayes Patterson Sims Libby Callaway Gavin Ivester Mike Smith Chase Cole Keith Meacham Ronnie Steine Jen Cole Ellen Meyer Joseph Sulkowski Stephanie Conner Dave Pittman Stacy Widelitz Gavin Duke Paul Polycarpou Betsy Wills Kristy Edmunds Anne Pope Mel Ziegler aA MESSAGE FROM OZ ARTS President John F. Kennedy had just been assassinated, the Civil Rights Act was mere months from inception, and the US was becoming more heavily involved in the conflict in Vietnam. It was 1964, and at The Factory in New York, Andy Warhol was experimenting with film. Over the course of two years, Andy Warhol selected regulars to his factory, both famous and anonymous that he felt had “star potential” to sit and be filmed in one take, using 100 foot rolls of film. It has been documented that Warhol shot nearly 500 screen tests, but not all were kept. Many of his screen tests have been curated into groups that start with “13 Most Beautiful…” To accompany these film portraits, Dean & Britta, formerly of the NY band, Luna, were commissioned by the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust and The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to create original songs, and remixes of songs from musicians of the era. This endeavor led Dean & Britta to a third studio album consisting of a total of 21 songs titled, “13 Most Beautiful.. -

NO RAMBLING ON: the LISTLESS COWBOYS of HORSE Jon Davies

WARHOL pages_BFI 25/06/2013 10:57 Page 108 If Andy Warhol’s queer cinema of the 1960s allowed for a flourishing of newly articulated sexual and gender possibilities, it also fostered a performative dichotomy: those who command the voice and those who do not. Many of his sound films stage a dynamic of stoicism and loquaciousness that produces a complex and compelling web of power and desire. The artist has summed the binary up succinctly: ‘Talk ers are doing something. Beaut ies are being something’ 1 and, as Viva explained about this tendency in reference to Warhol’s 1968 Lonesome Cowboys : ‘Men seem to have trouble doing these nonscript things. It’s a natural 5_ 10 2 for women and fags – they ramble on. But straight men can’t.’ The brilliant writer and progenitor of the Theatre of the Ridiculous Ronald Tavel’s first two films as scenarist for Warhol are paradigmatic in this regard: Screen Test #1 and Screen Test #2 (both 1965). In Screen Test #1 , the performer, Warhol’s then lover Philip Fagan, is completely closed off to Tavel’s attempts at spurring him to act out and to reveal himself. 3 According to Tavel, he was so up-tight. He just crawled into himself, and the more I asked him, the more up-tight he became and less was recorded on film, and, so, I got more personal about touchy things, which became the principle for me for the next six months. 4 When Tavel turned his self-described ‘sadism’ on a true cinematic superstar, however, in Screen Test #2 , the results were extraordinary. -

Exhibiting Warhols's Screen Tests

1 EXHIBITING WARHOL’S SCREEN TESTS Ian Walker The work of Andy Warhol seems nighwell ubiquitous now, and its continuing relevance and pivotal position in recent culture remains indisputable. Towards the end of 2014, Warhol’s work could be found in two very different shows in Britain. Tate Liverpool staged Transmitting Andy Warhol, which, through a mix of paintings, films, drawings, prints and photographs, sought to explore ‘Warhol’s role in establishing new processes for the dissemination of art’.1 While, at Modern Art Oxford, Jeremy Deller curated the exhibition Love is Enough, bringing together the work of William Morris and Andy Warhol to idiosyncratic but striking effect.2 On a less grand scale was the screening, also at Modern Art Oxford over the week of December 2-7, of a programme of Warhol’s Screen Tests. They were shown in the ‘Project Space’ as part of a programme entitled Straight to Camera: Performance for Film.3 As the title suggests, this featured work by a number of artists in which a performance was directly addressed to the camera and recorded in unrelenting detail. The Screen Tests which Warhol shot in 1964-66 were the earliest works in the programme and stood, as it were, as a starting point for this way of working. Fig 1: Cover of Callie Angell, Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests, 2006 2 How they were made is by now the stuff of legend. A 16mm Bolex camera was set up in a corner of the Factory and the portraits made as the participants dropped by or were invited to sit. -

The Films of Andy Warhol Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things

The Films of Andy Warhol Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things David Gariff National Gallery of Art If you wish for reputation and fame in the world . take every opportunity of advertising yourself. — Oscar Wilde In the future everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes. — attributed to Andy Warhol 1 The Films of Andy Warhol: Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things Andy Warhol’s interest and involvement in film ex- tends back to his childhood days in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Warhol was sickly and frail as a youngster. Illness often kept him bedridden for long periods of time, during which he read movie magazines and followed the lives of Hollywood celebri- ties. He was an avid moviegoer and amassed a large collection of publicity stills of stars given out by local theaters. He also created a movie scrapbook that included a studio portrait of Shirley Temple with the handwritten inscription: “To Andrew Worhola [sic] from Shirley Temple.” By the age of nine, Warhol had received his first camera. Warhol’s interests in cameras, movie projectors, films, the mystery of fame, and the allure of celebrity thus began in his formative years. Many labels attach themselves to Warhol’s work as a filmmaker: documentary, underground, conceptual, experi- mental, improvisational, sexploitation, to name only a few. His film and video output consists of approximately 650 films and 4,000 videos. He made most of his films in the five-year period from 1963 through 1968. These include Sleep (1963), a five- hour-and-twenty-one minute look at a man sleeping; Empire (1964), an eight-hour film of the Empire State Building; Outer and Inner Space (1965), starring Warhol’s muse Edie Sedgwick; and The Chelsea Girls (1966) (codirected by Paul Morrissey), a double-screen film that brought Warhol his greatest com- mercial distribution and success. -

September 19 Skype Chat in Dialogue Thierry Frémaux: Lumière! 1895

October 3 In person In Dialogue Virginia Heffernan: Magic and Loss, The Internet as Art Sponsor: Norwich Bookstore, Simon and Schuster Author, journalist and cultural critic (New York Times, Los Angeles Times), Virginia Heffernan sees the Internet as “the greatest masterpiece of human civilization,” steadily transforming all sensory and emotional experiences. Join us for a stimulating encounter with America’s most playful and engaging non-commentator commentator. Book signing follows talk. Devices welcome! October 10 In person Location: Rm 001, Black Family Visual Arts Center, Dartmouth College Audio-Vision Sources for 2001: A Space Odyssey Sponsors: Dartmouth’s Department of Music, Film and Media Studies Ciné Salon Fall 2016 celebrates 20 years of rare and classic Media artist Carlos Casa explores inspirations for director Stanley experiments in film introduced and discussed by some of the Kubrick’s 2001 with primary attention paid to the National Film world’s foremost authorities on media arts. More than 600 films Board of Canada documentary Universe, several visual music have screened in 269 thematic programs that have highlighted milestones, and Gyorgy Ligeti’s ethereal music compositions. genuinely engaging, often-difficult films and related subjects. FILMS: Universe (1960) Roman Kroitor, Colin Low; 28 min; Catalog (1961) John Whitney 8 min; Re-Entry (1963) Jordan Belson 6 min; audio only Atmosphères The anniversary emphasizes our commitment to keep alive the (1961) Gyorgy Ligeti 9 min. past, present and future of a vital art forum -

Marcel Duchamp / Andy Warhol.’ the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

CULTURE MACHINE REVIEWS • SEPTEMBER 2010 ‘TWISTED PAIR: MARCEL DUCHAMP / ANDY WARHOL.’ THE ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM, PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA. 23 MAY-12 SEPTEMBER 2010. Victor P. Corona Had he survived a routine surgical procedure, Andy Warhol would have turned eighty-two years old on August 6, 2010. To commemorate his birthday, the playwright Robert Heide and the artists Neke Carson and Hoop organized a party at the Gershwin Hotel in Manhattan’s Flatiron District. Guests in attendance included Superstars Taylor Mead and Ivy Nicholson and other Warhol associates. The event was also intended to celebrate the ‘Andy Warhol: The Last Decade’ exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum and the re-release of The Autobiography and Sex Life of Andy Warhol (Wilcock, 2010). Speaking with some of the Pop artist’s collaborators at the ‘Summer of Andy’ party served as an excellent prelude to my visit to an exhibition that traced Warhol’s aesthetic links to one of his greatest sources of inspiration, Marcel Duchamp. The resonances evident at the Warhol Museum’s fantastic ‘Twisted Pair’ show are not trivial: Warhol himself owned over thirty works by Duchamp. Among his collection is a copy of the Fountain urinal, which Warhol acquired by trading away three of his portraits (Wrbican, 2010: 3). The party at the Gershwin and the ‘Twisted Pair’ show also provided a fresh opportunity to explore the ongoing fascination with Warhol’s art as well as contemporary works that deal with the central themes that preoccupied him for much of his career. Since the relationship between the Dada movement and Pop artists has been intensely debated by others (e.g., Kelly, 1964; Madoff, 1997), this essay will instead focus on how Warhol’s art continues to nurture experimentation in the work of artists active today. -

Andy Warhol's Exploding Plastic Inevitable

Jean Wainwright Mediated Pain: Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable ‘Warhol has indeed put together a total environment. But it is an assemblage that actually vibrates with menace, cynicism and perversion. To experience it is to be brutalized, helpless…The Flowers of Evil are in full bloom with the Exploding, Plastic, Inevitable’.1 The ‘Exploding Plastic Inevitable’ (EPI) was Andy Warhol’s only foray into a total inter-media experience.2 From 1966 to 1967 the EPI, at its most developed, included up to three film projectors3, sometimes with colour reels projected over black and white, variable speed strobes, movable spots with coloured gels, hand-held pistol lights, mirror balls, slide projectors with patterned images and, at its heart, a deafening live performance by The Velvet Underground.4 Gerard Malanga’s dancing – with whips, luminous coloured tape and accompanied by Mary Woronov or Ingrid Superstar – completed the assault on the senses. [Fig.9.1] This essay argues that these multisensory stimuli were an arena for Warhol to mediate an otherwise internalised interest in pain, using his associates and the public as baffles to insulate himself from it. His management of the EPI allowed Warhol to witness both real and simulated pain, in a variety of forms. These ranged from the often extreme reactions of the viewing audience to the repetition on his background reels, projected over the foreground action.5 Warhol had adopted passivity as a self-fashioning device.6 This was a coping mechanism against being hurt, and a buffer to shield his emotional self from the public gaze.7 At the same time it became an effective manipulative device, deployed upon his Factory staff. -

This Face, Here, Now: Moving Image Portraiture” DOI: 10.5325/Jasiapacipopcult.2.1.0073

The Version of Record of this manuscript has been published and is available in The Journal of Asia-Pacific Popular Culture, 2:1, (2017). “This Face, Here, Now: Moving Image Portraiture” DOI: 10.5325/jasiapacipopcult.2.1.0073 This Face, Here, Now: Moving Image Portraiture Stephen Burstow Introduction What lies behind the photographic portrait of a face? A sovereign self? An essential character? For over a century, artists using photography have attempted to destabilise this notion of a unified personality that is transmitted through physical appearance. The multiple and extended exposures that fragmented and smeared the Pictorialist portrait in the early twentieth century have been joined in recent years by the digital reconfiguring of the face.1 This attack on the photographic portrait as a signifier of bourgeois individuation has also been aided by visual culture theorists such as Allan Sekula, who positioned the portrait in a hierarchical archive where “the look at the frozen gaze-of-the-loved-one was shadowed by two other more public looks: a look up, at one’s ‘betters,’ and a look down, at one’s ‘inferiors.’”2 Following in this tradition is the contemporary focus on the constraints of social media platforms that format and enable everyday digital portraiture, over and above the potential for psychological insight. These critiques, however, seem to have done little to dampen the everyday desire for inner lives to be revealed through represented faces. Consequently, some theorists have resorted to unconscious drives to explain viewers’ engagement with photographic portraits. For example, Lee Siegel, in an introductory essay to a major portraiture exhibition, claims that 1 For the challenge to the photographic portrait by twentieth-century photo-media artists see: Cornelia Kemp and Susanne Witzgall, The Other Face: Metamorphoses of the Photographic Portrait (München: Prestel, 2002). -

![Screen Tests Andy Warhol, Screen Test: Jane Holzer [ST141], 1964](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1947/screen-tests-andy-warhol-screen-test-jane-holzer-st141-1964-4621947.webp)

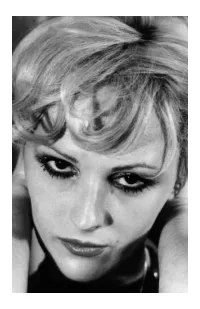

Screen Tests Andy Warhol, Screen Test: Jane Holzer [ST141], 1964

Screen Tests Andy Warhol, Screen Test: Jane Holzer [ST141], 1964, ©AWM © The Andy Warhol Museum, one of the four Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. All rights reserved. You may view and download the materials posted in this site for personal, informational, educational and non-commercial use only. The contents of this site may not be reproduced in any form beyond its original intent without the permission of The Andy Warhol Museum. except where noted, ownership of all material is The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Screen Tests Unknown, Concert poster (Open Stage: Andy Warhol and The Velvet Underground and Nico, at 23 St. Marks Place (Polska Narodny Dom ("The Dom")), New York, NY), 1966 © The Andy Warhol Museum, one of the four Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. All rights reserved. You may view and download the materials posted in this site for personal, informational, educational and non-commercial use only. The contents of this site may not be reproduced in any form beyond its original intent without the permission of The Andy Warhol Museum. except where noted, ownership of all material is The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Screen Tests Student sits for his screen test © The Andy Warhol Museum, one of the four Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. All rights reserved. You may view and download the materials posted in this site for personal, informational, educational and non-commercial use only. The contents of this site may not be reproduced in any form beyond its original intent without the permission of The Andy Warhol Museum. -

Who Was Andy Warhol? Ebook, Epub

WHO WAS ANDY WARHOL? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kirsten Anderson,Tim Salamunic,Nancy Harrison,Greg Copeland,Gregory Copeland | 112 pages | 26 Dec 2014 | Grosset & Dunlap | 9780448482422 | English | United States Who Was Andy Warhol? PDF Book The facial features and hair are screen-printed in black over the orange background. Warhol moved to New York right after college and worked there for a decade as a commercial illustrator. He founded the gossip magazine Interview , a stage for celebrities he "endorsed" and a business staffed by his friends. Many of his creations are very collectible and highly valuable. Up-tight: the Velvet Underground story. Born Andrew Warhola to poor Slovakian immigrants in the steel-producing city of Pittsburgh in , Warhol's chances of making it in the art world were slim. On February 20, , he was admitted to New York Hospital where his gallbladder was successfully removed and he seemed to be recovering. Warhol spoke to this apparent contradiction between his life and work in his book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol , writing that "making money is art and working is art, and good business is the best art. All of these films, including the later Andy Warhol's Dracula and Andy Warhol's Frankenstein , were far more mainstream than anything Warhol as a director had attempted. Warhol also loved to go to movies and started a collection of celebrity memorabilia, particularly autographed photos. Kunstmuseum Wolfsbug, Andy Warhol October Files. March 31, Watch and learn more. His most popular and critically successful film was Chelsea Girls In , Warhol turned his attention to the pop art movement, which began in Britain in the mids. -

ANDY WARHOL's NIGHT Musiques Nouvelles & Angélique Willkie

Transcultures, BAM, Pôle Muséal, Ville de Mons, Bozar ANDY WARHOL'S NIGHT Musiques Nouvelles & Angélique Willkie BAM – Beaux-Arts de Mons 8 & 9 janvier 2014 – 20:00 Flagey – Bruxelles 1er février 2014 – 20:15 ©Gerard Malanga / Andy Warhol and his media toys, 1971, courtesy Galerie Sandrine Mons 1 Sommaire Distribution……………………………………………………………………………………………………….p.3 Programme……………………………………………………………………………………………………….p.4 Textes et traductions…………………………………………………………………………………………p.4 Andy Warhol – Repères biographiques commentés………………………………………….p.9 Andy Warhol et la musique……………………………………………………………………………….p.12 Songs for Drella…………………………………………………………………………………………………p.13 Gerard Malanga………………………………………………………………………………………………..p.14 Angélique Willkie…..…………………………………………………………………………………………..p.14 Musiques Nouvelles…………………………………………………………………………………………..p.15 Pistes de lecture………………………………………………………………………………………………..p.15 Contacts…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….p.16 2 Distribution Hughes Kolp (guitare) – André Ristic (piano) – Jean-Paul Dessy (violoncelle) – Pierre Quiriny (percussions) – Jarek Frankowski (ingénieur du son) – Angélique Willkie (voix) Arrangements Stéphane Collin Dramaturgie Philippe Franck Textes & portraits d’archives Gerard Malanga Visuels Isabelle Françaix & Fabienne Wilkin Montage des visuels Yves Mora Costume & Maquillage Isa Belle ©Gerard Malanga / Portrait of the artist as a young man, 1964 «Analyser l’œuvre de Warhol au travers du prisme de la musique, du son, du silence, c’est réécouter toute son existence pour mieux l’entendre, en quelques mots raconter la trajectoire d’un artiste pop qui voulait être une pop star.» Nathalie Bondil, introduction à Warhol Live. Andy Warhol et la musique - Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal - 2009 Andy Warhol a marqué définitivement une culture «pop» peuplée d’icônes démultipliées et de superstars étincelantes. En 1963, il invente à Manhattan, la Factory, une usine à créer sans relâche des images, qui attire les jeunes talents, poètes, musiciens (du Velvet Underground à Bob Dylan) et illustres visiteurs du monde entier.