Program 8:30 – 8:50 AM Breakfast and Registration 8:50 – 9:00 AM Welcome from the President

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEEKING BLOSSOM in WINTER a National Theatre Wales Lab

SEEKING BLOSSOM IN WINTER A National Theatre Wales Lab “People think that their world will get smaller as they get older. My experience is just the opposite. Your senses become more active. You start to blossom.” Yoko Ono What is the older artist to do? Seeking Blossom in Winter was an investigation into the possibilities afforded by many years of radical performance practice and experience, led by Kevin Lewis. Bringing together four Wales-based artists in their 60s, with over 160 years of experience in ex- traordinary, radical performance practice between them, the project explored what happens when these artists encountered each other and started to play. Kevin collaborated with Jill Greenhalgh, Phillip MacKenzie and Belinda Neave. In Chapter Arts Centre in March I had the privilege of observing, documenting and occasionally provoking in the room. Early on the conversation was so rich and complex that the best thing I could do was just try to get it all down. We agreed afterwards that we’d publish it ‘warts and all’ - I’m of course typing at speed and sometimes am inaccurate to say the least - but that’s just what it is. As an archive of four extraordinary sensibilities in performance making in Wales (and way be- yond) it strikes me as important to try and link to as many of the references as I could, and I hope that this may be useful to other artists who may want to attempt to reach as far and wide in their learning and their practice. Alex Murdoch, Spring 2019 MONDAY MAKING A START and SHARING PROCESSES (They talk about the history of Chapter, and supporting work.) Phil mentions Isak Dinasen ‘The Blank Page’ Kevin - So the idea for this project is ‘What is an ageing artist to do?’ I was leaving Iolo and people kept saying to me ‘are you retiring?’. -

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson PACKET ONE 1. This character’s coach says that although it “takes all kinds to build a freeway” he is not equipped for this character’s kind of weirdness close the playoffs. This character lost his virginity to the homecoming queen and the prom queen at the same time and says he’ll be(*) “scoring more than baskets” at an away game and ends up in a teacher’s room wearing a thong which inspires the entire basketball team to start wearing them at practice. When Carrie brags about dating this character, Heather, played by Ashanti, hits her in the back of the head with a volleyball before Brittany Snow’s character breaks up the fight. Four girls team up to get back at this high school basketball star for dating all of them at once. For 10 points, name this character who “must die.” ANSWER: John Tucker [accept either] 2. The hosts of this series that premiered in 2003 once crafted a combat robot named Blendo, and one of those men served as a guest judge on the 2016 season of BattleBots. After accidentally shooting a penny into a fluorescent light on one episode of this show, its cast had to be evacuated due to mercury vapor. On a “Viewers’ Special” episode of this show, its hosts(*) attempted to sneeze with their eyes open, before firing cigarette butts from a rifle. This show’s hosts produced the short-lived series Unchained Reaction, which also aired on the Discovery Channel. -

Moma Andy Warhol Motion Pictures

MoMA PRESENTS ANDY WARHOL’S INFLUENTIAL EARLY FILM-BASED WORKS ON A LARGE SCALE IN BOTH A GALLERY AND A CINEMATIC SETTING Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures December 19, 2010–March 21, 2011 The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art Gallery, sixth floor Press Preview: Tuesday, December 14, 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. Remarks at 11:00 a.m. Click here or call (212) 708-9431 to RSVP NEW YORK, December 8, 2010—Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures, on view at MoMA from December 19, 2010, to March 21, 2011, focuses on the artist's cinematic portraits and non- narrative, silent, and black-and-white films from the mid-1960s. Warhol’s Screen Tests reveal his lifelong fascination with the cult of celebrity, comprising a visual almanac of the 1960s downtown avant-garde scene. Included in the exhibition are such Warhol ―Superstars‖ as Edie Sedgwick, Nico, and Baby Jane Holzer; poet Allen Ginsberg; musician Lou Reed; actor Dennis Hopper; author Susan Sontag; and collector Ethel Scull, among others. Other early films included in the exhibition are Sleep (1963), Eat (1963), Blow Job (1963), and Kiss (1963–64). Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures is organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Chief Curator at Large, The Museum of Modern Art, and Director, MoMA PS1. This exhibition is organized in collaboration with The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Twelve Screen Tests in this exhibition are projected on the gallery walls at large scale and within frames, some measuring seven feet high and nearly nine feet wide. An excerpt of Sleep is shown as a large-scale projection at the entrance to the exhibition, with Eat and Blow Job shown on either side of that projection; Kiss is shown at the rear of the gallery in a 50-seat movie theater created for the exhibition; and Sleep and Empire (1964), in their full durations, will be shown in this theater at specially announced times. -

Andy Warhol's

13 MOST BEAUTIFUL... SONGS FOR ANDY WARHOL’S SCREEN TESTS FEAUTURING DEAN & BRITTA JANUARY 17, 2015 OZ ARTS NASHVILLE SUPPORTS THE CREATION, DEVELOPMENT AND PRESENTATION OF SIGNIFICANT CONTEMPORARY PERFORMING AND VISUAL ART WORKS BY LEADING ARTISTS WHOSE CONTRIBUTION INFLUENCES THE ADVANCEMENT OF THEIR FIELD. ADVISORY BOARD Amy Atkinson Karen Elson Jill Robinson Anne Brown Karen Hayes Patterson Sims Libby Callaway Gavin Ivester Mike Smith Chase Cole Keith Meacham Ronnie Steine Jen Cole Ellen Meyer Joseph Sulkowski Stephanie Conner Dave Pittman Stacy Widelitz Gavin Duke Paul Polycarpou Betsy Wills Kristy Edmunds Anne Pope Mel Ziegler aA MESSAGE FROM OZ ARTS President John F. Kennedy had just been assassinated, the Civil Rights Act was mere months from inception, and the US was becoming more heavily involved in the conflict in Vietnam. It was 1964, and at The Factory in New York, Andy Warhol was experimenting with film. Over the course of two years, Andy Warhol selected regulars to his factory, both famous and anonymous that he felt had “star potential” to sit and be filmed in one take, using 100 foot rolls of film. It has been documented that Warhol shot nearly 500 screen tests, but not all were kept. Many of his screen tests have been curated into groups that start with “13 Most Beautiful…” To accompany these film portraits, Dean & Britta, formerly of the NY band, Luna, were commissioned by the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust and The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to create original songs, and remixes of songs from musicians of the era. This endeavor led Dean & Britta to a third studio album consisting of a total of 21 songs titled, “13 Most Beautiful.. -

NO RAMBLING ON: the LISTLESS COWBOYS of HORSE Jon Davies

WARHOL pages_BFI 25/06/2013 10:57 Page 108 If Andy Warhol’s queer cinema of the 1960s allowed for a flourishing of newly articulated sexual and gender possibilities, it also fostered a performative dichotomy: those who command the voice and those who do not. Many of his sound films stage a dynamic of stoicism and loquaciousness that produces a complex and compelling web of power and desire. The artist has summed the binary up succinctly: ‘Talk ers are doing something. Beaut ies are being something’ 1 and, as Viva explained about this tendency in reference to Warhol’s 1968 Lonesome Cowboys : ‘Men seem to have trouble doing these nonscript things. It’s a natural 5_ 10 2 for women and fags – they ramble on. But straight men can’t.’ The brilliant writer and progenitor of the Theatre of the Ridiculous Ronald Tavel’s first two films as scenarist for Warhol are paradigmatic in this regard: Screen Test #1 and Screen Test #2 (both 1965). In Screen Test #1 , the performer, Warhol’s then lover Philip Fagan, is completely closed off to Tavel’s attempts at spurring him to act out and to reveal himself. 3 According to Tavel, he was so up-tight. He just crawled into himself, and the more I asked him, the more up-tight he became and less was recorded on film, and, so, I got more personal about touchy things, which became the principle for me for the next six months. 4 When Tavel turned his self-described ‘sadism’ on a true cinematic superstar, however, in Screen Test #2 , the results were extraordinary. -

Exhibiting Warhols's Screen Tests

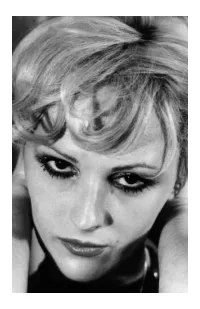

1 EXHIBITING WARHOL’S SCREEN TESTS Ian Walker The work of Andy Warhol seems nighwell ubiquitous now, and its continuing relevance and pivotal position in recent culture remains indisputable. Towards the end of 2014, Warhol’s work could be found in two very different shows in Britain. Tate Liverpool staged Transmitting Andy Warhol, which, through a mix of paintings, films, drawings, prints and photographs, sought to explore ‘Warhol’s role in establishing new processes for the dissemination of art’.1 While, at Modern Art Oxford, Jeremy Deller curated the exhibition Love is Enough, bringing together the work of William Morris and Andy Warhol to idiosyncratic but striking effect.2 On a less grand scale was the screening, also at Modern Art Oxford over the week of December 2-7, of a programme of Warhol’s Screen Tests. They were shown in the ‘Project Space’ as part of a programme entitled Straight to Camera: Performance for Film.3 As the title suggests, this featured work by a number of artists in which a performance was directly addressed to the camera and recorded in unrelenting detail. The Screen Tests which Warhol shot in 1964-66 were the earliest works in the programme and stood, as it were, as a starting point for this way of working. Fig 1: Cover of Callie Angell, Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests, 2006 2 How they were made is by now the stuff of legend. A 16mm Bolex camera was set up in a corner of the Factory and the portraits made as the participants dropped by or were invited to sit. -

Research Article

Research Article Embodied Curation: Materials, Performance and the Generation of Knowledge Andy Ditzler* Founder and Curator, Film Love Sydney M. Silverstein Department of Anthropology, Emory University *[email protected] Visual Methodologies: http://journals.sfu.ca/vm/index.php/vm/index Visual Methodologies, Volume 4, Number 1, pp.52-63. Ditzler and Silverstein Research Article The following essay unfolds as a conversation about the staging of a cinematographic tribute to Lou Reed and to the Velvet Underground’s early involvement with Andy Warhol and with underground cinema. The conversation—between the curator-host and an anthropologist-filmmaker present in the audience—pieces together personal registers of the event to make a case for embodied curation—a series of trans-disciplinary and multisensory research and performance practices that are generative of new ways of knowing about, and through, historical materials. Rather than a didactic endeavor, the encounters between curator, materials, and audience members generated new forms of embodied knowledge. Making a case for embodied methods of research and performance, we argue that this generation of knowledge was made possible only through the particular constellation of materials and practices that came together in the staging of this event. Keywords: Andy Warhol, Embodied Curation, Film Projection, Mechanical ABSTRACT Reproduction, Sensory Scholarship, Visual Methodologies. ISSN: 2040-5456 Copyright © 2016 The Research Methods Laboratory. 53 The equipment-free aspect of reality here has become the height of artifice; the sight of immediate reality has become an orchid in the land of technology. -Walter Benjamin “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”(1967: 233) Figure 1: Curator and projections, Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, February 21, 2014. -

The Films of Andy Warhol Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things

The Films of Andy Warhol Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things David Gariff National Gallery of Art If you wish for reputation and fame in the world . take every opportunity of advertising yourself. — Oscar Wilde In the future everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes. — attributed to Andy Warhol 1 The Films of Andy Warhol: Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things Andy Warhol’s interest and involvement in film ex- tends back to his childhood days in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Warhol was sickly and frail as a youngster. Illness often kept him bedridden for long periods of time, during which he read movie magazines and followed the lives of Hollywood celebri- ties. He was an avid moviegoer and amassed a large collection of publicity stills of stars given out by local theaters. He also created a movie scrapbook that included a studio portrait of Shirley Temple with the handwritten inscription: “To Andrew Worhola [sic] from Shirley Temple.” By the age of nine, Warhol had received his first camera. Warhol’s interests in cameras, movie projectors, films, the mystery of fame, and the allure of celebrity thus began in his formative years. Many labels attach themselves to Warhol’s work as a filmmaker: documentary, underground, conceptual, experi- mental, improvisational, sexploitation, to name only a few. His film and video output consists of approximately 650 films and 4,000 videos. He made most of his films in the five-year period from 1963 through 1968. These include Sleep (1963), a five- hour-and-twenty-one minute look at a man sleeping; Empire (1964), an eight-hour film of the Empire State Building; Outer and Inner Space (1965), starring Warhol’s muse Edie Sedgwick; and The Chelsea Girls (1966) (codirected by Paul Morrissey), a double-screen film that brought Warhol his greatest com- mercial distribution and success. -

September 19 Skype Chat in Dialogue Thierry Frémaux: Lumière! 1895

October 3 In person In Dialogue Virginia Heffernan: Magic and Loss, The Internet as Art Sponsor: Norwich Bookstore, Simon and Schuster Author, journalist and cultural critic (New York Times, Los Angeles Times), Virginia Heffernan sees the Internet as “the greatest masterpiece of human civilization,” steadily transforming all sensory and emotional experiences. Join us for a stimulating encounter with America’s most playful and engaging non-commentator commentator. Book signing follows talk. Devices welcome! October 10 In person Location: Rm 001, Black Family Visual Arts Center, Dartmouth College Audio-Vision Sources for 2001: A Space Odyssey Sponsors: Dartmouth’s Department of Music, Film and Media Studies Ciné Salon Fall 2016 celebrates 20 years of rare and classic Media artist Carlos Casa explores inspirations for director Stanley experiments in film introduced and discussed by some of the Kubrick’s 2001 with primary attention paid to the National Film world’s foremost authorities on media arts. More than 600 films Board of Canada documentary Universe, several visual music have screened in 269 thematic programs that have highlighted milestones, and Gyorgy Ligeti’s ethereal music compositions. genuinely engaging, often-difficult films and related subjects. FILMS: Universe (1960) Roman Kroitor, Colin Low; 28 min; Catalog (1961) John Whitney 8 min; Re-Entry (1963) Jordan Belson 6 min; audio only Atmosphères The anniversary emphasizes our commitment to keep alive the (1961) Gyorgy Ligeti 9 min. past, present and future of a vital art forum -

The Velvet Underground By: Kao-Ying Chen Shengsheng Xu Makenna Borg Sundeep Dhanju Sarah Lindholm Group Introduction

The Velvet Underground By: Kao-Ying Chen Shengsheng Xu Makenna Borg Sundeep Dhanju Sarah Lindholm Group Introduction The Velvet Underground helped create one of the first proto-punk songs and paved the path for future songs alike. Our group chose this group because it is one of those groups many people do not pay attention to very often and they are very unique and should be one that people should learn about. Shengsheng Biography The Velvet Underground was an American rock band formed in New York City in 1964. They are also known as The Warlocks and The Falling Spikes. Best-known members: Lou Reed and John Cale. 1967 debut album, “The Velvet Underground & Nico” was named the 13th Greatest Album of All Time, and the “most prophetic rock album ever http://t2.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcTpZBIJzRM1H- made” by Rolling Stone in 2003. GhQN6gcpQ10MWXGlqkK03oo543ZbNUefuLNAvVRA Ranked #19 on the “100 Greatest Artists of All Time” by Rolling Stone. Shengsheng Biography From 1964-1965: Lou Reed (worked as a songwriter) met John Cale (Welshman who came to United States to study classical music) and they formed, The Primitives. Reed and Cale recruited Sterling Morrison to play the guitar (college classmate of Reed’s) as a replacement for Walter De Maria. Angus MacLise joined as a percussionist to form a group of four. And this quartet was first named The Warlocks, then The Falling Spikes. Introduced by Michael Leigh, the name “The Velvet Underground” was finally adopted by the group in Nov 1965. Shengsheng Biography From 1965-1966: Andy Warhol became the group’s manager. -

Thirty Years After His Death, Andy Warhol's Spirit Is Still Very Much Alive by R.C

Thirty Years After His Death, Andy Warhol's Spirit Is Still Very Much Alive By R.C. Baker - Wednesday, February 22, 2017 at 9:30 a.m. I hate being odd in a small town If they stare let them stare in New York City* Andy Warhol, the striving son of Eastern European blue- collar immigrants, rose out of the cultural maelstrom of postwar America to the rarest of artistic heights, becoming a household name on the level of Michelangelo, Rembrandt, and Picasso. Warhol’s paintings of tragic celebrities and posterized flowers caught the 1960s zeitgeist by the tail, and he hung on right up until his death, thirty years ago this week, on February 22, 1987. He dazzled and/or disgusted audiences with paintings, films, installations, and happenings that delivered doses of shock, schlock, and poignance in equal measure. In retrospect, Warhol’s signature blend of high culture and base passion, of glitz and humanity, has had more lives than the pet pussycats that once roamed his Upper East Side townhouse. Two years before he died, Warhol published America, a small book that is more interesting for its writing than for the meandering black-and-white photographs of a one-legged street dancer cavorting on crutches, Sly Stallone’s cut physique, and other sundries. There is a striking passage accompanying shots of gravestones that eventually led to a posthumous joint project — fitting for an artist whose work had long involved collaboration. “I always thought I’d like my own tombstone to be blank,” Warhol had written. “No epitaph, and no name. -

A FICTION BROOKLYN ACADEMY of MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Executive Producer

Brooklyn Academy of Music SONGS FOR'DRELLA -A FICTION BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Executive Producer BAM Opera House November 29 - December 3, 1989 presents SONGS FOR 'DRELLA -A FICTION Music and Lyrics by Lou Reed and John Cale Set Design, Photography and Scenic Projections by Lighting Design by JEROME SIRLIN ROBERT WIERZEL Co-commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music NEXT WAVE Festival and The Arts at St. Ann's Joseph V. Melillo, Director, NEXT WAVE Festival SONGS FOR 'DRELLA-A FICTION Songs for 'Drella-a fiction is a brief musical look at the life of Andy Warhol and is entirely fictitious. We start with Andy growing up in a Sinalltown-"There's no Michelangelo coming from Pittsburgh." He comes to New York and follows the customs of"Open House" both in'his apartments and the Factory. "It's a Czechoslovakian custom my mother passed onto meltheway to makefriends Andyis to invite them upfor tea." He travels around the world and is in his words "Forever Changed." He knows the importance of people and money in the art world ["Style It Takes"] and follows his primary ethic, "Work-the most~portantthing is work." He can copy the classicists but feels "the trouble with classicists, they look at a tree/that's all they see/they paint a tree..." , Andy wished we all had the same "Faces and Names." He becomes involved with movies-"Starlight." He is interested in repetitive images-"I love images worth repeating••.see them with a different feeling." The mor tality rate at the Factory is rather high and some blame Andy-"Itwasn't me who shamed you..." The open house policy leads to him being shot ["I Believe"] and a new, locked door approach at the Factory causes him to wonder, "...if I have to live in fear/ where willI get my ideas...will I slowly Slip Away?" One night he has a dream, his relationships change..."A Nobody Like You." He dies recovering from a gall bladder operation.