Wim Wenders' Most Ambitious Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IDS 2935 Blues Music and Culture

IDS 2935 Blues Music and Culture University of Florida, Quest 1 / Identities Class # 21783 (face-to-face) / # 27957 (on-line) Semester: Spring 2021 Time/Location: T (Tuesdays Periods 5-6) / MAT 0115 (Face to Face section only) R (Thursdays) / MAT 0004 Virtual, Asynchronous Viewings of Assigned Documentaries and Videos, Independent Study General Education Designations: Humanities, Diversity Credits: 3 [Note: A minimum grade of C is required for General Education credit] Class resources, supplemental readings, assignments and announcements will be available via Canvas [URL] Instructor: Timothy J. Fik, Associate Professor | Department of Geography [e-mail: [email protected] ] Tim Fik Summer 2019 Office Location: 3137 Turlington Hall | Office Hours: Tuesdays & Thursday (Live) / 9:00AM- 11:00AM (or by appointment, please e-mail); Geography Department Phone: (352) 392-0494 ask for Dr. Fik. Feel free to contact me anytime: [email protected]. This course was originally designed as a traditional face-to-face class with a focus on the written and spoken exchange of ideas and concepts relating to course material. Note, however, that the structure of this "hybrid" course will have both a live face-to-face (f2f) component and a virtual/Independent Study/Asynchronous viewing component this semester for students registered for the f2f section. Students will engage in a series of assigned readings, documentary viewings, and discussions (through written comments/communication with the instructor and one another). Students are encourage to discuss material with board posts, e-mail, and group/class discussions. Weekly office hours, assignments, and term projects offer additional opportunities for personal engagement with course materials and the Instructor. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Ch 4, Launching the Peace Movement, and Skim Through Ch

-----------------~-----~------- ---- TkE u. s. CENT'R.A.L A.MERIC.A. PE.A.CE MOVEMENT' CHRISTIAN SMITH The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London List of Tables and Figures ix Acknowledgments xi Acronyms xiii Introduction xv portone Setting the Context 1. THE SOURCES OF CENTRAL AMERICAN UNREST 3 :Z. UNITED STATES INTERVENTION 18 J. Low-INTENSITY WARFARE 33 porttwo The Movement Emerges -'. LAUNCHING THE PEACE MOVEMENT 5 9 5. GRASPING THE BIG PICTURE 87 '. THE SOCIAL STRUCTURE OF MORAL OUTRAGE 13 3 '1'. THE INDIVIDUAL ACTIVISTS 169 porlthreeMaintaining the Struggle 8, NEGOTIATING STRATEGIES AND COLLECTIVE IDENTITY 211 1'. FIGHTING BATTLES OF PUBLIC DISCOURSE 231 1 O. FACING HARASSMENT AND REPRESSION 280 11. PROBLEMS FOR PROTESTERS CLOSER TO HOME 325 1%. THE MOVEMENT'S DEMISE 348 portfour Assessing the Movement 1J. WHAT DID THE MOVEMENT ACHIEVE? 365 1-'. LESSONS FOR SOCIAL-MOVEMENT THEORY 378 ii CONTENTS Appendix: The Distribution and Activities of Central America Peace Movement Organizations 387 Notes 393 Bibliography 419 ,igures Index 453 Illustrations follow page 208. lobles 1.1 Per Capita Basic Food Cropland (Hectares) 10 1.2 Malnutrition in Central America 10 7.1 Comparison of Central America Peace Activists and All Adult Ameri cans, 1985 171 7.2 Occupational Ratio of Central America Peace Movement Activist to All Americans, 1985 173 7.3 Prior Social Movement Involvement by Central American Peace Activists (%) 175 7.4 Central America Peace Activists' Prior Protest Experience (%) 175 7.5 Personal and Organizational vs. Impersonal -

Wenders Has Had Monumental Influence on Cinema

“WENDERS HAS HAD MONUMENTAL INFLUENCE ON CINEMA. THE TIME IS RIPE FOR A CELEBRATION OF HIS WORK.” —FORBES WIM WENDERS PORTRAITS ALONG THE ROAD A RETROSPECTIVE THE GOALIE’S ANXIETY AT THE PENALTY KICK / ALICE IN THE CITIES / WRONG MOVE / KINGS OF THE ROAD THE AMERICAN FRIEND / THE STATE OF THINGS / PARIS, TEXAS / TOKYO-GA / WINGS OF DESIRE DIRECTOR’S NOTEBOOK ON CITIES AND CLOTHES / UNTIL THE END OF THE WORLD ( CUT ) / BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB JANUSFILMS.COM/WENDERS THE GOALIE’S ANXIETY AT THE PENALTY KICK PARIS, TEXAS ALICE IN THE CITIES TOKYO-GA WRONG MOVE WINGS OF DESIRE KINGS OF THE ROAD NOTEBOOK ON CITIES AND CLOTHES THE AMERICAN FRIEND UNTIL THE END OF THE WORLD (DIRECTOR’S CUT) THE STATE OF THINGS BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Wim Wenders is cinema’s preeminent poet of the open road, soulfully following the journeys of people as they search for themselves. During his over-forty-year career, Wenders has directed films in his native Germany and around the globe, making dramas both intense and whimsical, mysteries, fantasies, and documentaries. With this retrospective of twelve of his films—from early works of the New German Cinema Alice( in the Cities, Kings of the Road) to the art-house 1980s blockbusters that made him a household name (Paris, Texas; Wings of Desire) to inquisitive nonfiction looks at world culture (Tokyo-ga, Buena Vista Social Club)—audiences can rediscover Wenders’s vast cinematic world. Booking: [email protected] / Publicity: [email protected] janusfilms.com/wenders BIOGRAPHY Wim Wenders (born 1945) came to international prominence as one of the pioneers of the New German Cinema in the 1970s and is considered to be one of the most important figures in contemporary German film. -

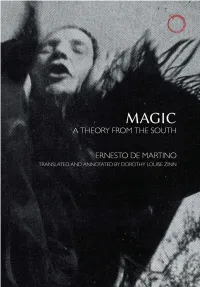

Magic: a Theory from the South

MAGIC Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com Magic A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH Ernesto de Martino Translated and Annotated by Dorothy Louise Zinn Hau Books Chicago © 2001 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano (First Edition, 1959). English translation © 2015 Hau Books and Dorothy Louise Zinn. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-9-9 LCCN: 2014953636 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Translator’s Note vii Preface xi PART ONE: LUcanian Magic 1. Binding 3 2. Binding and eros 9 3. The magical representation of illness 15 4. Childhood and binding 29 5. Binding and mother’s milk 43 6. Storms 51 7. Magical life in Albano 55 PART TWO: Magic, CATHOliciSM, AND HIGH CUltUre 8. The crisis of presence and magical protection 85 9. The horizon of the crisis 97 vi MAGIC: A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH 10. De-historifying the negative 103 11. Lucanian magic and magic in general 109 12. Lucanian magic and Southern Italian Catholicism 119 13. Magic and the Neapolitan Enlightenment: The phenomenon of jettatura 133 14. Romantic sensibility, Protestant polemic, and jettatura 161 15. The Kingdom of Naples and jettatura 175 Epilogue 185 Appendix: On Apulian tarantism 189 References 195 Index 201 Translator’s Note Magic: A theory from the South is the second work in Ernesto de Martino’s great “Southern trilogy” of ethnographic monographs, and following my previous translation of The land of remorse ([1961] 2005), I am pleased to make it available in an English edition. -

Sat 22 Jul – Wed 23 Aug

home box office mcr. 0161 200 1500 org home road movies Sat 22 Jul – Wed 23 Aug Vanishing Point1 , 1971 ROAD MOVIES . From the earliest days of American cinema, the road movie has been synonymous with American culture and the image America has presented to the world. In its most basic form, the charting of a journey by an individual or group as they seek out some form of adventure, redemption or escape, is a sub-genre that ranks amongst American cinema’s most enduring gifts to contemporary film culture. homemcr.com/road-movies 2 3 CONTENTS Road Movie + ROAD ........................................................................................6 The Last Detail ..................................................................................................8 The Wizard of Oz ...........................................................................................10 Candy Mountain ............................................................................................. 12 The Motorcycle Diaries .................................................................................14 Wim Wenders Road Trilogy ..........................................................................16 Vanishing Point ................................................................................................18 Landscape in the Mist .................................................................................. 20 Leningrad Cowboys Go America ...............................................................22 4 5 A HARD ROAD TO TRAVEL: ROAD MOVIE (CTBA) -

The Fall of the Wall: the Unintended Self-Dissolution of East Germany’S Ruling Regime

COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN, ISSUE 12 /13 131 The Fall of the Wall: The Unintended Self-Dissolution of East Germany’s Ruling Regime By Hans-Hermann Hertle ast Germany’s sudden collapse like a house of cards retrospect to have been inevitable.” He labeled this in fall 1989 caught both the political and academic thinking “whatever happened, had to have happened,” or, Eworlds by surprise.1 The decisive moment of the more ironically, “the marvelous advantage which historians collapse was undoubtedly the fall of the Berlin Wall during have over political scientists.”15 Resistance scholar Peter the night of 9 November 1989. After the initial political Steinbach commented that historians occasionally forget upheavals in Poland and Hungary, it served as the turning very quickly “that they are only able to offer insightful point for the revolutions in Central and Eastern Europe and interpretations of the changes because they know how accelerated the deterioration of the Soviet empire. Indeed, unpredictable circumstances have resolved themselves.”16 the Soviet Union collapsed within two years. Along with In the case of 9 November 1989, reconstruction of the the demolition of the “Iron Curtain” in May and the details graphically demonstrates that history is an open opening of the border between Hungary and Austria for process. In addition, it also leads to the paradoxical GDR citizens in September 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall realization that the details of central historical events can stands as a symbol of the end of the Cold War,2 the end of only be understood when they are placed in their historical the division of Germany and of the continent of Europe.3 context, thereby losing their sense of predetermination.17 Political events of this magnitude have always been The mistaken conclusion of what Reinhard Bendix the preferred stuff of which legends and myths are made of. -

Kings of the Road

KINGS OF THE ROAD KINGS OF THE ROAD is about a friendship between two men: Bruno, aka “King of the Road” (Rüdiger Vogler), who repairs film projectors and travels along the inner-German border in his truck, and the psychologist Robert, aka “Kamikaze” (Hanns Zischler), who is fleeing from his own past. When Robert drives his old VW straight into the Elbe river, he is fished out by Bruno. This is the beginning of their shared journey through a german No Man’s land, a journey that leads them from the Lüneburg Heath to the Bavarian Forest. Wenders began the film without a script. Instead there was a route that he had scouted out beforehand: all of the little towns along the Wall that still contained a movie theater in this era of cinematic mass extinction. The old moving van with the film projectors in the back becomes a metaphor of the history of film - it is no coincidence that the film is dedicated to Fritz Lang. This “men’s story” also treats the themes of the absence of women, of loneliness and of post-war Germany. At one point Bruno says to Robert: “The Yankees have colonized our subconscious.” Hans Dieter Traier (Paul, garage owner), Franziska KINGS OF THE ROAD Stömmer (Cinema owner), Peter Kaiser (Movie presenter), Patrick Kreuzer (Little boy), Michael West Germany 1975 Wiedemann (Teacher) Script: FESTIVALS & AWARDS Gretl Zeilinger, Brigitte Thoms 1976 Cannes International Filmfestival: FIPRESCI-Prize Assistant Director: 1976 Chicago International Film Festival: Gold Hugo Martin Hennig (Best Film) Music: FORMAT Improved Sound Limited, Axel Linstädt Length: 175 min, 4784 m In Cooperation with: Westdeutscher Rundfunk (Cologne) Format:! 35mm black and white; 1:1.66; Sound Re-recording Mixer: Paul Schöler Language: German Technician: 4K Restoration 2014 Hans Dreher, Volker von der Heydt Set Design: CREDITS Heidi Lüdi, Bernd Hirskorn Production: Truck: Wim Wenders Produktion (München) Michael Rabl Director: Songs: Wim Wenders Chrispian St. -

FM 271 the Films of Wim Wenders

FM 271 The Films of Wim Wenders Seminar Leader: Matthias Hurst Email: [email protected] Office Hours (P 98, Room 003): Tuesday, 13.30 – 15.00, or by appointment Course Times: Friday, 14.00 – 17.15; Wednesday, 19.30 – 22.00 (weekly film screening) Course Description Wim Wenders is one of Germany’s best known and most prolific filmmakers. He was a major representative of New German Cinema and the so-called Autorenfilm in the 1970s and 1980s, and an important artistic voice for the post-war generation. In addition, he became a celebrated figure in international cinema, making films in locations all over the world, and contributing to the genre of documentary as well as the development of the feature film. As film historians have noted, Wenders is notoriously difficult to classify in terms of cultural traditions or cinematic movements; thus exploring Wenders’s development as filmmaker implies looking at different aesthetic and narrative approaches to cinema, from auteur cinema to modern and postmodern film. His two most famous works Paris, Texas (1984), set in the desolate American West, and Wings of Desire (1987), a gripping portrait of the divided city of Berlin, encapsulate his wide-ranging scope and experimental power. We will consider these two works within Wim Wenders’s career, which includes Alice in the Cities (1974), Kings of the Road (1976), The American Friend (1977), The End of Violence (1997), Buena Vista Social Club (1999), The Million Dollar Hotel (2000), Land of Plenty (2004), Don’t Come Knocking (2005), Every Thing Will Be Fine (2015), Submergence (2017). -

On Space in Cinema

1 On Space in Cinema Jacques Levy Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne [email protected] Abstract The relationship between space and cinema is problematic. Cinema can be seen as a spatial art par excellence, but there are good reasons why this view is superficial. This article focuses on geographical films, which aim to increase our understanding of this dimension of the social world by attempting to depict inhabited space and the inhabitance of this space. The argument is developed in two stages. First, I attempt to show the absence both of space as an environment and of spatiality as an agency in cinematographic production. Both of these contribute to geographicity. Second, I put forward and expand on the idea of opening up new channels between cinema and the social sciences that take space as their object. This approach implies a move away from popular fiction cinema (and its avatar the documentary film) and an establishment of links with aesthetic currents from cinema history that are more likely to resonate with both geography and social science. The article concludes with a “manifesto” comprising ten principles for a scientific cinema of the inhabited space. Keywords: space, spatiality, cinema, history of cinema, diegetic space, distancing, film music, fiction, documentary, scientific films Space appears to be everywhere in film, but in fact it is (almost) nowhere. This observation leads us to reflect on the ways in which space is accommodated in films. I will focus in particular on what could be termed “geographical” films in the sense that they aim to increase our understanding of this dimension of the social world by 2 attempting to depict inhabited space and the inhabitance of this space. -

XXI:11) Wim Wenders, WINGS of DESIRE/DER HIMMEL ÜBER BERLIN (1987, 128 Min

November 9, 2010 (XXI:11) Wim Wenders, WINGS OF DESIRE/DER HIMMEL ÜBER BERLIN (1987, 128 min) Directed by Wim Wenders Written by Wim Wenders, Peter Handke and Richard Reitinger Produced by Anatole Dauman and Wim Wenders Music by Laurie Anderson, Jürgen Knieper, Laurent Petitgand, Nick Cave Cinematography by Henri Alekan Film Editing by Peter Przygodda Dedicatees: Yasujiro Ozu, François Truffaut, and Andrzei Tarkovsky as Andrzej Bruno Ganz....Damiel Solveig Dommartin....Marion Otto Sander....Cassiel Curt Bois....Homer, the aged poet Peter Falk....Der Filmstar WIM WENDERS (14 August 1945,Düsseldorf, North Rhine- Westphalia, Germany) has directed 45 films, among them Don't Come Knocking 2005, Land of Plenty 2004, “The Soul of a Man” Maudits/The Damned 1947, La Belle et la bête/Beauty and the episode in the PBS series “The Blues” 2003, Buena Vista Social Beast 1946, Vénus aveugle/Blind Venus 1941 and La Vie est à Club 1999, Willie Nelson at the Teatro 1998, The End of nous/The People of France. Violence 1997, Lumière et compagnie/Lumière and Company 1996, Lisbon Story 1994, Bis ans Ende der Welt/Until the End of BRUNO GANZ (22 March 1941, Zürich-Seebach, Switzerland) the World 1991, Wings of Desire/Hummel über Berlin (1987), has acted in 86 films, the most recent of them The Great Farrell Paris, Texas 1984, Hammett 1982, Lightning Over Water/Nick’s 2006 (in production). Some of the others are Der Untergang Film 1980, Der Amerikanische Freund/The American Friend 2004, The Manchurian Candidate 2004, Mia aioniotita kai mia 1977, Der Scharlachrote Buchstabe/The Scarlet Letter 1973, Die mera/Eternity and a Day 1998, Prague 1992, Strapless 1989, Angst des Tormanns beim Elfmeter/The Goalie's Anxiety at the The Legendary Life of Ernest Hemingway 1988, Killer aus Penalty Kick 1972, Alabama: 2000 Light Years from Home 1969, Forida 1983, Rece do gory/Hands Up! 1981, Nosferatu: and Schauplätze 1967.