Ch 4, Launching the Peace Movement, and Skim Through Ch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................2 2. The Principles of Anarchism, Lucy Parsons....................................................................3 3. Anarchism and the Black Revolution, Lorenzo Komboa’Ervin......................................10 4. Beyond Nationalism, But not Without it, Ashanti Alston...............................................72 5. Anarchy Can’t Fight Alone, Kuwasi Balagoon...............................................................76 6. Anarchism’s Future in Africa, Sam Mbah......................................................................80 7. Domingo Passos: The Brazilian Bakunin.......................................................................86 8. Where Do We Go From Here, Michael Kimble..............................................................89 9. Senzala or Quilombo: Reflections on APOC and the fate of Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio...........................................................................................................................91 10. Interview: Afro-Colombian Anarchist David López Rodríguez, Lisa Manzanilla & Bran- don King........................................................................................................................96 11. 1996: Ballot or the Bullet: The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Electoral Process in the U.S. and its relation to Black political power today, Greg Jackson......................100 12. The Incomprehensible -

Jewish Dimensions of a Free Church Ecclesiology: a Community of Contrast

Jewish Dimensions of a Free Church Ecclesiology: A Community of Contrast A research proposal by drs. Daniël Drost, April 2012 Supervised by Prof. Fernando Enns (promoter). Professor of Mennonite (Peace-) Theology and Ethics, Faculteit der Godgeleerdheid, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Director of the Institute for Peace Church Theology, Hamburg University. Dr. Henk Bakker. Universitair docent Theologie en Geschiedenis van het Baptisme, Faculteit der Godgeleerdheid, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Prof. Peter Tomson (extern). Professor of New Testament, Jewish Studies, and Patristics, Faculteit voor Protestantse Godgeleerdheid Brussel. The provisional title (and subtitle) of the dissertation Jewish Dimensions of a Free Church Ecclesiology: A Community of Contrast A brief description of the issue which the research project will investigate The research will start by investigating John Howard Yoder’s perspective on what he provocatively calls the ‘Jewishness of the Free Church Vision.’ Strongly recommended by Stanley Hauerwas (Duke University), Michael Cartwright (Dean of Ecumenical and Interfaith Programs at the University of Indianapoils) and Peter Ochs (Modern Judaistic Studies at the University of Virginia) posthumously edited and commented on Yoder’s lectures, which he had presented at the Roman- Catholic University of Notre Dame (The Jewish Christian Schism Revisited, 2003). Mennonite theologian Yoder does a firm attempt to relate an Anabaptist (Free Church) ecclesiology to Judaism. Within the tradition of the free churches (independence from government, congregational structure, voluntary membership, emphasis on individual commitment etc.) we can identify characteristics of a self-understanding and an aspired relation to the larger society, which can also be traced in the story of the People of Israel, the Hebrew Bible, Second Temple and rabbinic Diaspora Judaism – Yoder claims. -

Educating for Peace and Justice: Religious Dimensions, Grades 7-12

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 392 723 SO 026 048 AUTHOR McGinnis, James TITLE Educating for Peace and Justice: Religious Dimensions, Grades 7-12. 8th Edition. INSTITUTION Institute for Peace and Justice, St. Louis, MO. PUB DATE 93 NOTE 198p. AVAILABLE FROM Institute for Peace and Justice, 4144 Lindell Boulevard, Suite 124, St. Louis, MO 63108. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Conflict Resolution; Critical Thinking; Cross Cultural Studies; *Global Education; International Cooperation; *Justice; *Multicultural Education; *Peace; *Religion; Religion Studies; Religious Education; Secondary Education; Social Discrimination; Social Problems; Social Studies; World Problems ABSTRACT This manual examines peace and justice themes with an interfaith focus. Each unit begins with an overview of the unit, the teaching procedure suggested for the unit and helpful resources noted. The volume contains the following units:(1) "Of Dreams and Vision";(2) "The Prophets: Bearers of the Vision";(3) "Faith and Culture Contrasts";(4) "Making the Connections: Social Analysis, Social Sin, and Social Change";(5) "Reconciliation: Turning Enemies and Strangers into Friends";(6) "Interracial Reconciliation"; (7) "Interreligious Reconciliation";(8) "International Reconciliation"; (9) "Conscientious Decision-Making about War and Peace Issues"; (10) "Solidarity with the Poor"; and (11) "Reconciliation with the Earth." Seven appendices conclude the document. (EH) * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are -

Jewish-Christian Dialogue Under the Shadow of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Gregory Baum

Document generated on 10/02/2021 6:07 p.m. Théologiques Jewish-Christian Dialogue under the Shadow of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Gregory Baum Juifs et chrétiens. L’à-venir du dialogue. Volume 11, Number 1-2, Fall 2003 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/009532ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/009532ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Faculté de théologie de l'Université de Montréal ISSN 1188-7109 (print) 1492-1413 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Baum, G. (2003). Jewish-Christian Dialogue under the Shadow of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Théologiques, 11(1-2), 205–221. https://doi.org/10.7202/009532ar Tous droits réservés © Faculté de théologie de l'Université de Montréal, 2003 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Théologiques 11/1-2 (2003) p. 205-221 Jewish-Christian Dialogue under the Shadow of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Gregory Baum Religious Studies McGill University Prior to World War II, Jewish religious thinkers who moved beyond the tradition of Orthodoxy were in dialogue with modern culture, including dialogue with Christian thinkers who were also searching new religious responses to the challenge of modernity. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit?

The “Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit? A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Hornstein Jewish Professional Leadership Program Professors Ellen Smith and Jonathan Krasner Ph.D., Advisors In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Leah Robbins May 2020 Copyright by Leah Robbins 2020 Acknowledgements This thesis was made possible by the generous and thoughtful guidance of my two advisors, Professors Ellen Smith and Jonathan Krasner. Their content expertise, ongoing encouragement, and loving pushback were invaluable to the work. This research topic is complex for the Jewish community and often wrought with pain. My advisors never once questioned my intentions, my integrity as a researcher, or my clear and undeniable commitment to the Jewish people of the past, present, and future. I do not take for granted this gift of trust, which bolstered the work I’m so proud to share. I am also grateful to the entire Hornstein community for making room for me to show up in my fullness, and for saying “yes” to authentically wrestle with my ideas along the way. It’s been a great privilege to stretch and grow alongside you, and I look forward to continuing to shape one another in the years to come. iii ABSTRACT The “Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit? A thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Leah Robbins Fascination with the famed “Black-Jewish coalition” in the United States, whether real or imaginary, is hardly a new phenomenon of academic interest. -

Selected Chronology of Political Protests and Events in Lawrence

SELECTED CHRONOLOGY OF POLITICAL PROTESTS AND EVENTS IN LAWRENCE 1960-1973 By Clark H. Coan January 1, 2001 LAV1tRE ~\JCE~ ~')lJ~3lj(~ ~~JGR§~~Frlt 707 Vf~ f·1~J1()NT .STFie~:T LA1JVi~f:NCE! i(At.. lSAG GG044 INTRODUCTION Civil Rights & Black Power Movements. Lawrence, the Free State or anti-slavery capital of Kansas during Bleeding Kansas, was dubbed the "Cradle of Liberty" by Abraham Lincoln. Partly due to this reputation, a vibrant Black community developed in the town in the years following the Civil War. White Lawrencians were fairly tolerant of Black people during this period, though three Black men were lynched from the Kaw River Bridge in 1882 during an economic depression in Lawrence. When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1894 that "separate but equal" was constitutional, racial attitudes hardened. Gradually Jim Crow segregation was instituted in the former bastion of freedom with many facilities becoming segregated around the time Black Poet Laureate Langston Hughes lived in the dty-asa child. Then in the 1920s a Ku Klux Klan rally with a burning cross was attended by 2,000 hooded participants near Centennial Park. Racial discrimination subsequently became rampant and segregation solidified. Change was in the air after World "vV ar II. The Lawrence League for the Practice of Democracy (LLPD) formed in 1945 and was in the vanguard of Post-war efforts to end racial segregation and discrimination. This was a bi-racial group composed of many KU faculty and Lawrence residents. A chapter of Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) formed in Lawrence in 1947 and on April 15 of the following year, 25 members held a sit-in at Brick's Cafe to force it to serve everyone equally. -

The European Union's Policy Towards Mercosur

towards Mercosur towards policy Union’s The European EPRU The European Union’s policy towards Mercosur European Series Policy This book provides a distinctive and empirically rich account of the European Research Union’s (EU’s) relationship with the Common Market of the South (Mercosur). It seeks to examine the motivations that determine the EU’s policy towards Unit Mercosur, the most important relationship the EU has with another regional Series economic integration organization. In order to investigate these motivations (or lack thereof), this study The European examines the contribution of the main policy- and decision-makers, the European Commission and the Council of Ministers, as well as the different contributions of the two institutions. It analyses the development of EU policy towards Mercosur in relation to three key stages: non-institutionalized Union’s policy relations (1986–1990), official relations (1991–1995), and the negotiations for an association agreement (1996–2004 and 2010–present). Arana argues that the dominant explanations in the literature fail to towards adequately explain the EU’s policy – in particular, these accounts tend to infer the EU’s motives from its activity. Drawing on extensive primary documents, the book argues that the major developments in the relationship were initiated by Mercosur and supported mainly by Spain. Rather than Mercosur the EU pursuing a strategy, as implied by most of the existing literature, the EU was largely responsive, which explains why the relationship is much less developed than the EU’s relations with other parts of the world. The European Union’s policy towards Mercosur will benefit academics and Responsive not strategic postgraduate students of European Union Foreign Affairs, inter-regionalism Gomez Arana and Latin American regionalism. -

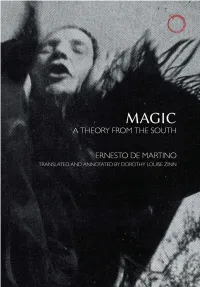

Magic: a Theory from the South

MAGIC Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com Magic A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH Ernesto de Martino Translated and Annotated by Dorothy Louise Zinn Hau Books Chicago © 2001 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano (First Edition, 1959). English translation © 2015 Hau Books and Dorothy Louise Zinn. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-9-9 LCCN: 2014953636 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Translator’s Note vii Preface xi PART ONE: LUcanian Magic 1. Binding 3 2. Binding and eros 9 3. The magical representation of illness 15 4. Childhood and binding 29 5. Binding and mother’s milk 43 6. Storms 51 7. Magical life in Albano 55 PART TWO: Magic, CATHOliciSM, AND HIGH CUltUre 8. The crisis of presence and magical protection 85 9. The horizon of the crisis 97 vi MAGIC: A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH 10. De-historifying the negative 103 11. Lucanian magic and magic in general 109 12. Lucanian magic and Southern Italian Catholicism 119 13. Magic and the Neapolitan Enlightenment: The phenomenon of jettatura 133 14. Romantic sensibility, Protestant polemic, and jettatura 161 15. The Kingdom of Naples and jettatura 175 Epilogue 185 Appendix: On Apulian tarantism 189 References 195 Index 201 Translator’s Note Magic: A theory from the South is the second work in Ernesto de Martino’s great “Southern trilogy” of ethnographic monographs, and following my previous translation of The land of remorse ([1961] 2005), I am pleased to make it available in an English edition. -

Introduction

Introduction Introduction In this book I have gathered documents that show how war tax resistance devel- oped in the Society of Friends in America and how Quaker war tax resistance was seen by other Americans. These documents highlight the search for truth within the Society of Friends as well as the interest, concern, and occasional aggravation of those outside of the Society who found themselves trying to understand or nav- igate the Quaker point of view. Here, I’ll introduce some of the common themes found in these documents. The bounds to Quaker taxpaying were marked by two Biblical instructions in particular, found in Romans 13 and Acts 5. The first says: Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers. For there is no power but of God: the powers that be are ordained of God. Whosoever therefore resists the power, resists the ordinance of God.... ye must needs be subject, not only for wrath, but also for conscience sake. For for this cause pay ye tribute also... The second provides an exception to the rule: We ought to obey God rather than men. Much of the debate about Quaker war tax resistance, both inside the Society of Friends and with its critics, centered on how liberally this exception was to be interpreted. Does providing funds to help the government make war violate God’s commands in a way that triggers this exception, or are today’s higher powers no less deserving of tribute than was Cæsar in his day? A typical Quaker war tax resistance position went something like this: We must cheerfully pay taxes for the support of civil government even when that gov- ernment uses the tax money to fund a budget that includes military spending, but we must refuse to pay any tax that is levied expressly for the purpose of conduct- ing a war or supporting the military. -

Army for Progress: the U.S. Militarization of the Guatemalan

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Master's Theses 1995 ARMY FOR PROGRESS : THE U.S. MILITARIZATION OF THE GUATEMALAN POLITICAL AND SOCIAL CRISIS 1961-1969 Michael Donoghue University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses Recommended Citation Donoghue, Michael, "ARMY FOR PROGRESS : THE U.S. MILITARIZATION OF THE GUATEMALAN POLITICAL AND SOCIAL CRISIS 1961-1969" (1995). Open Access Master's Theses. Paper 1808. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses/1808 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARMY FOR PROGRESS : THE U.S. MILITARIZATION OF THE GUATEMALAN POLITICAL AND SOCIAL CRISIS 1961-1969 BY MICHAELE.DONOGHUE A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND - ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to explore the military and political implications of the United States' foreign policy towards Guatemala in the years 1961 to 1969. Guatemala was a key battleground of the Cold War in Latin America in the crucial decade of the 1960s. While greater scholarly attention has focused on the 1954 U.S. backed CIA planned cou~ in Guatemala, the events of the 1960s proved an equally significant watershed in U.S.-Latin American relations. Tue outbreak of a nationalist insurgency in Guatemala early in the decade provided the Kennedy Administration with a vital testing ground for its new counter-insurgency and civic action politico-military doctrine. -

Sat 22 Jul – Wed 23 Aug

home box office mcr. 0161 200 1500 org home road movies Sat 22 Jul – Wed 23 Aug Vanishing Point1 , 1971 ROAD MOVIES . From the earliest days of American cinema, the road movie has been synonymous with American culture and the image America has presented to the world. In its most basic form, the charting of a journey by an individual or group as they seek out some form of adventure, redemption or escape, is a sub-genre that ranks amongst American cinema’s most enduring gifts to contemporary film culture. homemcr.com/road-movies 2 3 CONTENTS Road Movie + ROAD ........................................................................................6 The Last Detail ..................................................................................................8 The Wizard of Oz ...........................................................................................10 Candy Mountain ............................................................................................. 12 The Motorcycle Diaries .................................................................................14 Wim Wenders Road Trilogy ..........................................................................16 Vanishing Point ................................................................................................18 Landscape in the Mist .................................................................................. 20 Leningrad Cowboys Go America ...............................................................22 4 5 A HARD ROAD TO TRAVEL: ROAD MOVIE (CTBA)